Journalist James Fox is a former feature writer and foreign correspondent for London’s Sunday Times. His writing has appeared in Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, London Review of Books, and The Observer, among other publications. He is the co-author of Keith Richards’s memoir Life, awarded the 2011 Norman Mailer Prize for Biography.

And we understand him well,

How he comes oe’r us with our wilder days,

Not measuring what use we made of them.

—Shakespeare, Henry V

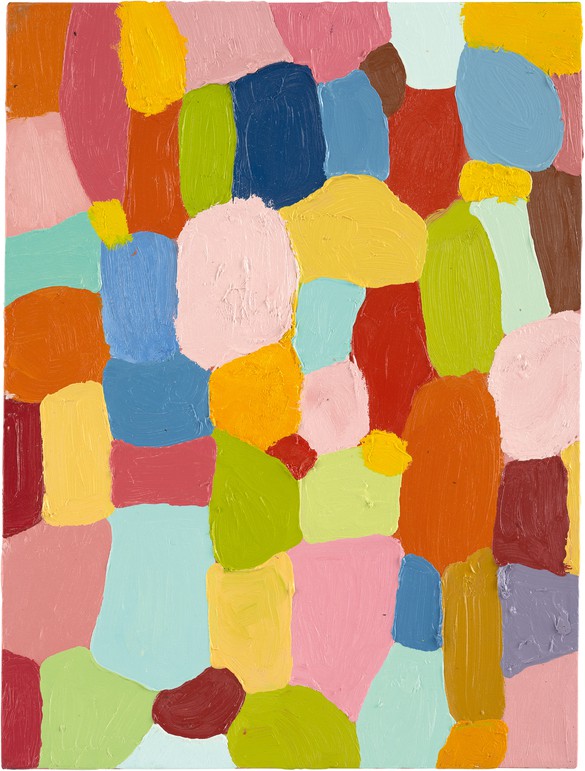

Rarely exhibited, Damien Hirst’s Visual Candy paintings are a vital link in the chronology of the artist’s creative journey as well as a display of his core love of painting, to which he has reverted, periodically, in times of solitude or as an antidote to the sculptural, conceptual, and studio-assisted works for which he is famous. On display beside them, in a 2017–18 exhibition at Gagosian in Hong Kong, were some of the earliest vitrine sculptures in his Natural History series—specimens of sharks, cows, sheep in formaldehyde that are exactly contemporaneous with the Visual Candy period.

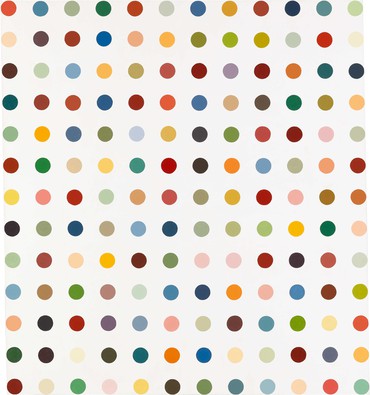

The series of contemplative, vivid, almost nostalgic high-color paintings was begun, in multiples, in New York, during the most intense period of creativity and expansion in Hirst’s early career. He had arrived for a six-month stay in September 1992, for three shows in rapid succession, having already made his major attention-getting breakthroughs in London and elsewhere. To the original Freeze show in 1988, when Hirst, still at Goldsmiths College in London, first found fame by galvanizing and launching his fellow “Young British Artists,” to his flies sculpture A Thousand Years (1990), which caught the attention of Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, and to his In and Out of Love butterfly paintings (1991), Hirst had added, and first exhibited in March 1992, his giant shark in formaldehyde, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991). The shark sculpture had by itself changed contemporary art. His Spot paintings had just seen the light of day that same year. Hirst had captured and conquered the imagination of the art world and already established his major works, which had undoubtedly widened the art public to include many who had never been to an art gallery—in London at least. But compared with New York then, it was, to Hirst, a provincial success. Alone among the Young British Artists, he was ambitious to cross the water.

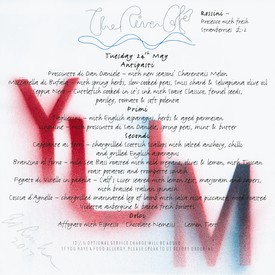

Two gallerists in New York were crucial early promoters of Hirst’s work. Clarissa Dalrymple, who had been the first to show many cutting-edge artists, including Matthew Barney, was organizing shows for Gladstone Gallery, and she included Hirst in an exhibition called British Art in September, the month of his arrival. And Tanya Bonakdar gave him a solo show in December at Cohen Gallery, where he first showed Pharmacy, now in the permanent collection of the Tate—wall-to-wall cabinets fully stocked with colorful pill packaging. Sandwiched between these was Hirst’s first solo exhibition, at Jay Chiat and Donatella Brun’s New York apartment in October, which included vitrine works, then in full production.

“I was looking to be somebody in New York,” Hirst told me. “It was romantic. I was looking to expand. I wanted this art wheel I’d created to keep growing and wanted what was happening to keep happening. I was on a crazy roll and I didn’t want anything to stop it. And I thought my ideas were more suited to America.” Damien, with his partner, clothing and jewelry designer Maia Norman, and their friend, the artist, writer, and curator Daniel Moynihan, moved into Jasper Johns’s building downtown at Howard Street, which was being managed by the artist Julian Lethbridge. Hirst rented two floors—one of them Johns’s former studio—and Moynihan rented the floor above. There, as Hirst put it, “We settled in for six mad months.” This was where Hirst began work on the Visual Candy paintings, painting them horizontally on the floor of the studio. The fact that these works were described as a sideline at the time shows just how mad the months must have become, to accommodate the fast-moving production line of Hirst’s other works, as well, and the exceptionally hard partying that took place almost every night of the week with Hirst and his newfound New York friends.

Visual Candy, which was exhibited the following year, in July 1993, at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, started as a reaction to an art critic’s describing the newly launched Spot paintings as “just visual candy.” “I couldn’t get it out of my head. I thought, what . . . is wrong with visual candy?” said Hirst. Why was there a stigma attached to art considered merely pleasing to the eye? There was also the Warhol dictum, which Hirst quotes: “Don’t think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide if it’s good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they are deciding, make even more art.”

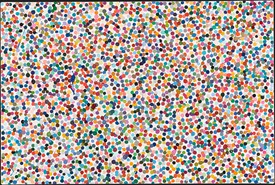

The Visual Candy paintings, like the Spot paintings, are explorations in the management of color, representing neatly the argument, always in Hirst’s mind, between Expressionism and Minimalism. “I was always a colorist,” he told his friend Gordon Burn. “I always had a phenomenal love of color; I wanted to be a complete colorist.” It was, early on, Henri Matisse, with his The Snail (1953)—“a spiral made with squares in a rectangle”—and, above all, Pierre Bonnard who triggered his overarching love of color, Hirst says. “I had to do spots on the wall because I couldn’t paint,” he says. “I don’t know where the idea came from. I used to do these little collages, and then I used to try and paint them. As soon as I painted onto them, I destroyed them; I fucked them up. I used to have to be really careful: get in there, and get out. I couldn’t succeed in what I was trying to do. So that’s what the Spot paintings came from, to create that structure to do those colors and do nothing, I suddenly got what I wanted. It was just a way of pinning down the joy of color. I was trying to let the formal thing fuck up the decision-making process or obscure it.”

“I’ve always seen the Spot paintings as a kind of metaphor for all painting,” the artist Michael Craig-Martin, Hirst’s former tutor at Goldsmiths, told me. “All the elements that all paintings have are in those Spot paintings.” As a result, the Spot paintings, originally conceived as an endless series—as a collective work—became flawless and perfect-looking vehicles of color in the hands of studio assistants; the carefully sanded and painted surfaces were a part of their shimmering effect, each painting with a different combination of colors. Visual Candy was an antidote to that perfection—the old pull of Expressionism versus Minimalism that has always been a part of Hirst’s preoccupation with the act of painting, a conflict that goes back to his days in the Foundation Course at Leeds. “My heart was always in that type of painting,” he told me:

I love [Willem] de Kooning, Patrick Heron and Ivon Hitchens and Peter Lanyon. I’d been taught by a not very well known painter from the ’50s and ’60s at Jacob Kramer called Patrick Oliver, and he was all about paint-how-you-feel and abstraction to communicate self-expression and all that stuff, and I think because I’d had a little bit of success with Minimalism with the Spots and the medicine cabinets, I thought, well, yeah, I’ve done it your way but now I want to do it my way, and it was a last attempt at that. I should have realized by the size I made the paintings I obviously didn’t have the confidence in that kind of art anymore. The Spot paintings I’d made at that point had been massive, and I did a big switch-down in scale for these paintings, even though the studio I had could have accommodated bigger paintings. I’d lost belief in that kind of painting, but I couldn’t let go. I remember friends being surprised I was doing blobby paintings with oil paints, kind of like ironic, jokey Nicolas de Staël paintings. I was watching a kids’ cartoon on American TV a lot at that time called Ren & Stimpy. Jay Chiat had turned me on to it because he was doing something with them with his advertising agency. It was totally surreal. I think I named a painting after a song in one of the shows called “Happy Happy Joy Joy”—the titles are mostly in that vein. A lot of the colors came from that cartoon. But people didn’t get what I was doing. I wasn’t surprised, because I wasn’t sure either. The Visual Candy paintings felt like they should come before the Spots, but here I was, doing them after.

Friends indeed were surprised. Hirst had fallen in with a gang of the most progressive, cutting-edge artists in New York, as was his intention, and they weren’t primarily into blobs of oil paint. In the same spirit as Freeze, he wanted his most talented contemporaries to come together, exchange ideas, form a bow wave. Hirst believed in generosity, inclusiveness, and encouragement as the way to make it work, which was the secret behind the success of the Young British Artists movement and also vital to Hirst’s own development. The locus for gatherings of Hirst and his New York friends was the East Village and its more obscure bars and pool halls—an area with an already legendary reputation, to which they added their mark. “Nineties New York was pretty good,” says Hirst: “Ashley Bickerton, Mike Joo, Matthew Barney, Cady Noland, Rirkrit Tiravanija—who was doing meals as artworks—and his partner, painter Elizabeth Peyton; Rob Pruitt, Sylvie Fleury, Michael Joaquin Grey, John Currin, Sean Landers, Alexis Rockman. And Felix Gonzalez-Torres. It was super happening.”

Most of the group showed in the huge gathering of talent in Aperto ’93 at the 1993 Venice Biennale, where Hirst showed, for the first time, his Mother and Child (Divided) (1993)—two pairs of glass-walled tanks, each containing half of a cow or a calf in formaldehyde—which ignited the usual mix of intense admiration and shocked hostility.

Hirst’s attachment to the paint-how-you-feel Expressionism of his earliest student days at Jacob Kramer College (now Leeds Arts University) is a tugging on his memory that came full circle again in 2018. Visual Candy inspired his two Gagosian exhibitions in that year: The Veil Paintings, in Los Angeles in the spring, with the same layered brushstrokes and bright dabs of paint in vast fields of color, and Colour Space Paintings, shown in New York in the summer of 2018, in which the Spots returned to their rare original prototypes, with drips and inconsistencies from the human hand replacing the humming mirage of machine-like perfection. Says Hirst of Visual Candy, “Although the lack of confidence I felt about them at the time makes me cringe a bit, it was an important step for me. It’s who I am. And if you look at the Veil paintings, it’s taken me all that time, twenty-five years or more, to get them where I wanted them to be. And the world’s changed too, to make them work.”

Damien Hirst: Visual Candy and Natural History, Gagosian, Hong Kong, November 23, 2017–March 3, 2018

Artwork © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

Text published in Damien Hirst: Visual Candy and Natural History (New York: Gagosian, 2021)