Virginia Shore is an art curator, advisor, and advocate living in Washington, DC. She is currently collaborating with the Emerson Collective, Halcyon Arts Lab, and the Hall Group on public art projects. Previously, Ms. Shore was the Chief Curator of the US Department of State’s Art in Embassies (AIE) program.

The strength of a nation derives from the integrity of the home.

—Confucius, Analects, sixth–fifth century BC

Home is the place that, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

—Robert Frost, “The Death of the Hired Man,” 1905/1906

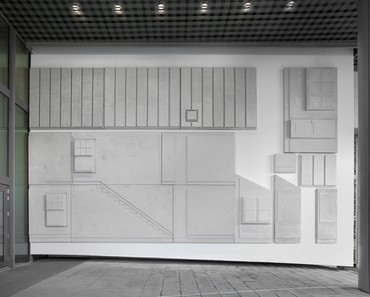

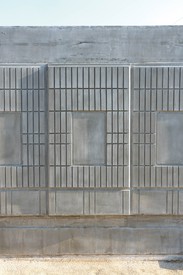

Rachel Whiteread’s monumental new work US Embassy (Flat pack house) (2013–15) is first encountered in the approach to the new American embassy in Nine Elms, South London. The work begins outdoors under the building’s covered consular entrance, pauses with its glass wall, and continues inside, where visitors are greeted and directed into the building. Here Whiteread has installed casts of the complete interior of a two-story prefabricated house, in thirty-one unique elements spanning the entire height and length of these soaring walls.

The vertical mounting wraps the visitor in the familiar constituents of home; we recognize the outlines of staircases, windows, architraves, outlets, roofing, wall decor, flooring, and tiling. Yet the inverted presentation unsettles. Cast in a light-gray concrete that augments the details and surfaces, the panels bestow presence on the absent interior of the house, breathing life into features often overlooked. As the light changes and moves along the surface of each element, varying depths teach a lesson in geometry, illuminating and obscuring shapes, lines (vertical and horizontal), cut-out spaces, diagonals, rectangles, squares within rectangles, and triangles embedded within horizontal reveals, all in a poetic play of shadow and rhythm.

The US Embassy in London stood for many years in Grosvenor Square, Mayfair. State-of-the-art security needs and inevitable expansion were the driving force for the move to the Nine Elms site, which President George W. Bush signed a conditional agreement to acquire in 2008 (despite the recent claims by President Donald Trump that the decision had been one of the mistakes of his more direct predecessor, Barack Obama). As plans developed, the London embassy became the most ambitious commission to date for the State Department’s Art in Embassies program (AIE), which has created more than seventy-five permanent collections for new American embassies and consulates around the world since 2005, and thousands of temporary exhibitions in ambassadorial residences since 1963. Thematically, the curatorial focus of the commissions for these new embassies and consulates has orbited around ideas of national identity, and on the exploration, through art and culture, of critical connections and juxtapositions between the host country and the United States. In addition to Whiteread’s installation, the London embassy demonstrates that inquiry with works by a mix of host-country and American artists: Mark Bradford, Cerith Wyn Evans, Ryan and Hays Holladay, Jenny Holzer, Idris Khan, Richard Long, Catherine Opie, Eva Rothschild, Sean Scully, Barbara Walker, and Alison Watt.

As the site of a country’s diplomatic representation in another country, an embassy has many roles, one of which is to promote its home culture, science, and economy in the hearts of its host. Although embassies are often considered “foreign soil,” they actually remain part of the territory of the receiving state, but they are protected with significant privileges that make them effectively inviolable. As such, they hold a peculiar status as places in which two countries play the roles of both host and home. Regardless, for many the real significance of an embassy is the link and lifeline it provides to one’s home when abroad. US Embassy (Flat pack house) greets all who come to the embassy to deal with consular affairs and issues that typically have a personal impact: birth, death, marriage, adoption, child custody, citizenship, movement among countries. This public place is where intensely private matters are addressed—where the refuge of home is longed for and missed.

In 2012, with the design for the new US Embassy well underway, I approached Gagosian Gallery requesting a meeting with Rachel Whiteread about a potential commission there. My hope in engaging her was spurred by her demonstrated commitment to public artworks, which has led her to make four exceptional memorial sculptures in London and Vienna over the past twenty years. Her work has been described as a form of social renewal, responding to and conveying the complexity of history and memory. Inspired by her stature as the first woman to win Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize, I was also aware that Whiteread has acknowledged the influence of American artists such as Donald Judd, Bruce Nauman, and Gordon Matta-Clark, and has spoken of her sympathy for the American Romantics Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. I felt certain that her contribution would be powerful and consequential. We met a few months later and discussed the broad parameters of the commission, the physical site, and the cultural-diplomacy objective of demonstrating similarities or productive differences between our two countries and cultures.

Whiteread’s inspired and compelling response was to create a transcendent work referencing affordable and transitional housing in both the United States and Britain. The theme has deep historical resonance in the two countries, recalling our shared trajectories and intertwined histories. Prefabricated buildings served as dwellings throughout Britain’s colonial expansion. They provided critical accommodation for military and civilian personnel during and following both world wars. To replace homes destroyed by bombing during the second of these wars, Winston Churchill sponsored a government program to provide temporary prefabricated homes developed in consultation with American engineers. Prototypes were erected outside the Tate in Millbank to demonstrate their ease and speed of construction, raising public enthusiasm for the initiative. Over 156,000 of these houses—many of them proving not so temporary, for they are still standing today—sprang up throughout Britain to give refuge to those made homeless by the wreckage of war.

In the United States, meanwhile, prefabricated buildings sheltered hopeful miners in the California Gold Rush of the 1840s and ’50s. As in the United Kingdom, military personnel lived in prefabricated buildings through both world wars, and some of these structures were later adapted to house families during peacetime. The American dream of home ownership meanwhile propelled the popularity of the flat pack, the home delivered in a kit. Between 1908 and 1940, the catalogue company Sears, Roebuck produced over 70,000 models of such homes, bearing picturesque names such as Alhambra, Rosita, Savoy, Cinderella, Windsor, Hollywood, and Betsy Ross to feed the fantasies and aspirations of middle-class Americans. These havens could be customized with features both basic and ornate, and were available on advantageous borrowing terms. As materials were developed and adapted to reduce building costs and the need for skilled labor, home ownership became an achievable ambition.

US Embassy (Flat pack house) embraces these histories of renewal, optimism, and striving, and similar creative adaptations were necessary to realize the work itself. Whiteread, AIE, and the embassy’s architects struggled for months, for example, with the formula for the concrete, which had to be light enough for the building’s structure to bear its weight. The solution ultimately proved to be concrete reinforced with glass, a material that is lightweight but strong and allows for finer detail than traditional concrete generally does.

Home is the place that, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

Robert Frost

The symbolism of the home as cultural connector is profound. Here Whiteread responded to the site, acknowledging the complex significance of home for travelers abroad. Her sculpture is a still life, showing no obvious residue of human presence, yet its quiet bulk elicits a vast range of visual, cognitive, and emotional responses. The work emphasizes the solemn, the stoic, and the heroic. Human ambition and promise are dignified and memorialized by its silent spaces. “Home” conjures up ideas of warmth, family, love, security, and harmony, but also the threat and reality of their loss.

“Home” also signifies origin, place, and belonging; its meanings inevitably provoke social comment and question, underscoring the critical state of the world today, with its large forced movements of refugees and migrants. Prefabricated buildings currently provide refuge for many of the 65 million displaced people around the globe, while upward of 1.6 billion people struggle without adequate shelter. US Embassy (Flat pack house) honors those lives and admonishes our complacency. We are sheltered by the work, comforted by its familiar forms, and disquieted by its ambiguity. While the notion of home may transport viewers to their own personal space, their own idea of domesticity, this archetypal flat-pack house is disorienting and mysterious. It is a cast of space, made inside a home that was or that may be, invoking memory and hope. It embodies paradox, home away from home, absence and presence together. Consciously and unconsciously, US Embassy (Flat pack house) will connect all who pass through it with a human aspiration as basic as breath: the longing for home. As we face the piece, the electrical outlets also remind that this particular home is distinctly American.

On January 12, 2017, Whiteread was awarded the State Department’s Medal of Arts, acknowledging her work and her enduring commitment to cultural diplomacy through the visual arts and international cultural exchange. She is recognized as defining a generation through her artistic excellence and her belief in the underlying premise of art as a potential unifier. US Embassy (Flat pack house) humanizes and energizes the new embassy, creating an environment that opens dialogue and forges cultural links. As Whiteread has said, “I don’t think art changes the world in terms of stopping people dying of AIDS or of starvation or being homeless. But for an individual, seeing a great piece of art can take you from one place to another—it can enhance daily life, reflect our times, and, in that sense, change the way you think and are.”

Artwork © Rachel Whiteread; photos: Mike Bruce