Alexander Wolf is a director at Gagosian in New York. Since 2013, his projects at the gallery have included exhibitions, communications, and online initiatives. He has written for the Quarterly on Piero Golia, Nam June Paik, Robert Therrien, and other gallery artists.

Even among the steadfastly independent artists of his circle—Joseph Beuys, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, George Maciunas, Charlotte Moorman, and others—Nam June Paik’s artistic journey stands out for its fluidity over mediums and continents. Following a decade of musical study and performance in Asia and Europe, Paik came fully equipped to the Happenings-centered scene of downtown Manhattan in 1964, jolting the Fluxus movement with performances that demonstrated his musical and technological acuity and his absolute openness to the inflections of chance. The audio/visual pastiches that remain—in the forms of found-object sculptures, installations of modified TVs, fast-paced video mixes, handmade robots, paintings, drawings, and combinations of the above—are active artifacts of his quest to humanize or naturalize advances in technology, particularly in TV, video, and radio, mediums that he co-opted to broadcast his art and that of his peers to the world. “Skin has become inadequate in interfacing with reality,” Paik wrote. “Technology has become the body’s new membrane of existence.”1 Twelve years after his death, Paik’s questioning of where human and nature end and tech begins is only more prescient, as personal devices are increasingly relied upon to expedite basic actions such as communicating, eating, sleeping, and moving from point A to point B, not to mention more complex endeavors such as learning languages, tracing ancestry, and finding love.

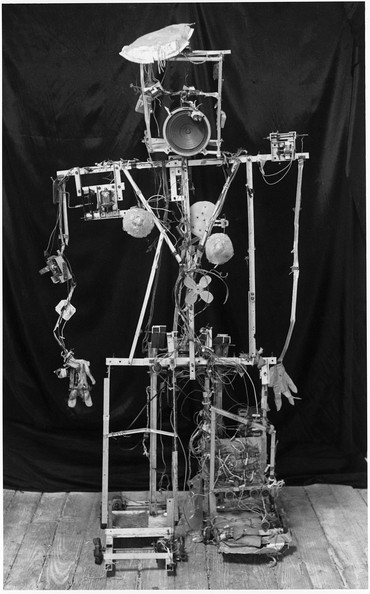

Paik closely followed and made use of evolutions in tech, to unexpected ends. Many of his works reveal a desire to familiarize television and other technologies, to make sense of these rapidly developing fields within the known framework of the natural world. Paik touched down in New York after a yearlong stay in Tokyo, bringing with him K-456, a remote-controlled robot that he had built in aluminum with the electronics engineer Shuya Abe, with whom he would later collaborate on the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer (1969–72). Named after a Mozart piano concerto, Robot K-456 was outfitted with rubber breast paddings, a tin-foil pie plate as a hat, and an electric fan as a navel; could walk, talk, and wave; and was often modified to perform new functions for performances.2 “I imagined it would meet people on the street and give them a split-second surprise,” Paik said, “like a sudden shower.”3 Days after his arrival in New York, Paik met Moorman, a twenty-four-year-old Juilliard-trained cellist and protagonist of the avant-garde music scene. Paik and Robot K-456 performed several weeks later in Moorman’s second Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York, in which the robot played a recording of President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address and defecated white beans.4

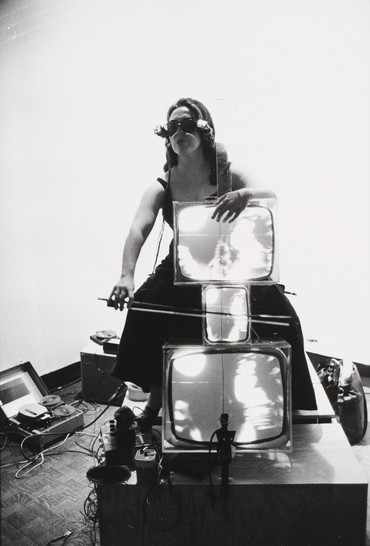

Paik had planned to spend six months in New York. Despite his first impressions of the city—“as ugly as Düsseldorf, and as dirty as Paris”—he would make it his home from then on, and Moorman would remain a key collaborator and muse.5 Between 1969 and 1972, Paik made four works specifically for her use in performances: TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), TV Cello (1971), TV Glasses (1971), and TV Bed (1972). Echoing Paik’s robot in their technological humanism, each work was activated by Moorman’s physical engagement. TV Bra comprises two miniature televisions, attached to vinyl straps, that Moorman wore across her chest as she played the cello, which partly covered the rest of her.6 (As Hilton Als of the New Yorker recently observed, “Moorman took her cello and married it to her body.”)7 TV Cello is a stack of three TVs—the smallest sandwiched in the middle to mimic the shape of the instrument—with a vertical bow of four thick wires. As the instrument was played, the screens showed footage of Moorman and other cellists mixed with live images of the present performance. TV Glasses likewise showed live images on two tiny screens covering Moorman’s eyes, while TV Bed comprises eighteen monitors face-up on the floor between a headboard and a footboard.8 Although these works built for physical interaction cannot be called useful devices, they portend the wearable digitized products—glasses, earphones, watches, wristbands—that many now use to stream video, communicate, measure heart rates, count steps, and simulate or “augment” reality by, for example, bringing three-dimensional images from the news of the day into the living room. Designed to rest on the body as comfortably as possible, such devices make up the new skin whose encroachment Paik already felt in the 1960s, resubstantiating his prophetic conflations of tech and the body.

In subsequent works, Paik used animals, plants, and natural events, both present and recorded, to further interrogate the relationship of tech to nature, as well as the line between reality and representation that technological developments can blur. In Video Fish (1975), aquarium tanks full of fish are set in front of monitors playing footage of . . . fish. “The real environment of the fish placed over the recorded one of the television set causes the monitor to become a fish tank and the fish tank a monitor,” wrote curator and Paik expert John Hanhardt in 1982. “Here, representation and reality join together as equals.”9 Paik’s compressions of present and recorded action, like Moorman’s live performances incorporating video mixes, elegantly represent the tech/life paradox that was central to his thinking by requiring the viewer to distinguish between reality and recorded representation.

TV Garden (1974–78) likewise pairs recorded imagery with natural elements. Placed among lush plants like bright electronic blooms, the sets play Paik’s Global Groove (1973), an all-encompassing video and audio patchwork that juxtaposes images of performer friends such as Cage, Cunningham, and Moorman with traditional Korean and African dancers and with American jazz and rock. Here Paik draws parallels between the growth of plants and the development of television as a fertile technology.10 TV Garden also evokes the beauty of chance, apparent throughout nature and also throughout Paik’s video and television work. As Paik explained, “My experimental TV is not always interesting but not always uninteresting. Like nature, which is beautiful, not because it changes beautifully, but simply because it changes.”11 Calvin Tomkins wrote in 1975, “A true disciple of Cage, Paik did not want to make anything that would be a mere reflection of his own personality. What he was after was indeterminacy—the image created by chance—and he found that the behavior of electrons in a color television set was truly indeterminate.”12 Paik described his primary medium as “video compost”: disparate imagery from seemingly infinite sources that he constantly combined and reedited, poeticizing the potential of technology to connect a heterogeneous planet.

The diversity of Paik’s imagery reflects not only his global trajectory but his roots in musical performance and collaboration. His early work as a musician and composer cannot be overemphasized in discussing the active and inclusive nature of his sculpture, a normally static medium. Following studies with the German composer Wolfgang Fortner, Paik worked from the late 1950s at the Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, where he integrated “acoustic events” into his music.13 Through performances and happenings that he termed “Action Music,” Paik, like Cage, sought to emphasize the music of everyday life and in the late 1950s and early ’60s created instruments for the purpose, which audience members were invited to play: a modified piano containing light bulbs, telephones, and alarm clocks; a colander outfitted with a bell; a violin with a twine leash meant to be dragged in the street. In 1963 Paik made Zen for TV, a television, turned on its side, that he altered so that it displays only a single vertical line, evoking a stringed instrument.14 Two years later came Magnet TV (1965), in which Paik invited viewers to alter a television’s transmission by moving a large magnet across its top. The performative and engaging nature of these early works endures through Paik’s television sculptures of the next forty years, many of which have invited the viewer’s participation. At minimum they reward being watched (as one watches a performance) rather than simply seen.

As familiar carriers of images from around the world, TVs were the natural vessels for Paik’s art. His first solo exhibition, at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany, in March of 1963, included thirteen secondhand televisions scattered around the apartment gallery. Paik had modified the TVs’ components to produce unusual effects, and continued to do so for the duration of the ten-day show, a work in progress in which he and his peers kept tinkering with the TVs and three “prepared pianos.” Beuys, for his part, attacked one of the pianos with an axe in an impromptu “action.”15 The exhibition, billed as Exposition of Music—Electronic Television, is now considered an early milestone in video art. “It was the first time Paik appropriated television technology and it signaled the beginning of a lifelong effort to deconstruct and demystify television,” observes Hanhardt. “With sets randomly distributed in all positions throughout the gallery, each television became an instrument, removed from its customary entertainment context, handled and manipulated in a direct and physical way.”16 As such, the TVs announced themselves as a new medium that by its nature provided an endless supply of current, exploitable images. Paik used them to locate intersections among technology, spirituality, art, music, and nature. Like Robert Rauschenberg’s reflective White Paintings of 1951, and Cage’s compositions featuring ordinary sounds, Paik’s televisions frame reality. Rauschenberg said of his White Paintings, “It is completely irrelevant that I am making them—Today is their creater [sic].”17 Paik might have said the same of his altered TVs.

As TVs became ubiquitous in the home, Paik saw them as surfaces with as much potential for meaningful manipulation as the canvas. As an artist who had been awakened at a young age to the music of life by Cage, and to the symbolic power of everyday objects by Beuys and Marcel Duchamp, he was perhaps uniquely positioned to do so. Paik delighted in fresh innovations and found the screen of great use as a frame for a wide spectrum of imagery; yet his works, assembled and often painted by hand, also remain solidly within the world of painting and sculpture. In an effort to humanize the technologies he engaged, many of his sculptures are figurative or physically engage the human form. These include robots, TV screens with painted facial features, and works made to be worn or handled in performances.

Following a major stroke in 1996, Paik, ambitious as ever, began to infuse his TV sculptures with notes of personal and spiritual reflection. He made sculptural video homages to artist friends and gesturally painted and inscribed the old TVs and other found objects that crowded his studio, producing multilayered works that fulfill a promise he had made as a young and determined artist (while assembling his Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer) “to shape the TV screen canvas as precisely as Leonardo/as freely as Picasso/as colorfully as Renoir/as profoundly as Mondrian/as violently as Pollock/as lyrically as Jasper Johns.”18 In an increasingly connected world, will tomorrow’s artists aspire to shape their works as eclectically as Paik?

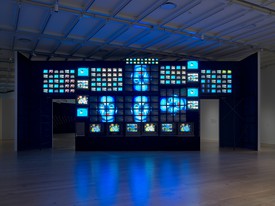

“After his stroke, Paik would sit in a wheelchair at his worktable in his studio, surrounded by Buddha statues, toys, birdcages, old television sets, radios, drawing paper and canvases, paintbrushes, felt markers, and other objects,” recalls Hanhardt.19 At the time, nature videos provided solace. Few works embody Paik’s ability to fuse the forces of tech, nature, performance, and human expression as compellingly as the monumental installation Lion (2005), one of his final television sculptures. Lion’s twenty-eight monitors—whose screens measure anywhere from 5 to 58 inches wide—form a towering arch, which frames a found wooden statue of a lion that Paik tattooed all over with his signature TV pictograph and signed multiple times in English, Japanese, and Korean. The screens show electronically produced images of flowers, fish, and other natural subjects, as well as footage of lions in the wild. Lion also conveys Paik’s reflective spirit in the twilight of his life: clips of his old friend Cunningham performing appear alongside the flora and fauna.20

Following its role in Moorman’s Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York and several appearances through the end of the 1960s, Robot K-456 reemerged for Paik’s Whitney Museum retrospective in 1982. Paik planned a performance in which the robot began to cross Madison Avenue via remote control, was struck by a car, and fell to the pavement. Hanhardt, who organized the retrospective, remembers, “When interviewed by the television news reporters documenting the event, Paik described the accident as the first catastrophe of the twenty-first century, and added that we were practicing how to cope with it. This catastrophe was the sense, created by the impact of new technologies, that things were out of control, that our lives and environment were threatened.”21

Paik’s most enduring assertion may be that art that claims to engage life must now also engage tech. As curator Michelle Yun observes, “Paik was adamant that it was the artist’s duty to reimagine technology in the service of art and culture.”22 Those who pursue a balance between life and the inescapable realm of cyberspace might consider his straightforward prescription, made in 1986, that “our life is half natural and half technological. Half-and-half is good.”23 Paik made poetry of this inevitable coexistence.

1Nam June Paik, quoted in Eva Respini, Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, exh. cat. (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), p. 78.

2 See Reuben Hoggett, “1964–Robot K-456–Nam June Paik (Korean) & Shuya Abe (Japanese),” cyberneticzoo.com: a history of cybernetic animals and early robots, online at http://cyberneticzoo.com/robots-in-art/1964-robot-k-456-nam-june-paik-korean-shuya-abe-japanese/ (accessed March 2018).

3 Paik, quoted in “Nam June Paik, ‘Robot K-456,’” Medien Kunst Netz/Media Art Net, online at http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/robot-k-456/ (accessed March 2018).

4 See Calvin Tomkins, “Profiles: Video Visionary,” The New Yorker, May 5, 1975. Available online at http://www.namjunepaik.eu/category.php?category=32 (accessed March 2018).

5 Ibid.

6 See John G. Hanhardt, “Paik’s Video Sculpture,” in Hanhardt, Nam June Paik, exh. cat. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1982), pp. 95–97.

7 Hilton Als, “The Legacy of the ‘Topless Cellist,’” The New Yorker, September 12, 2016. Available online at www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/12/charlotte-moorman-the-topless-cellist (accessed February 2018).

8 See Hanhardt, “Paik’s Video Sculpture,” pp. 95–97.

9 Ibid., p. 98.

10 See Hanhardt, “Non-Fatal Strategies: The Art of Nam June Paik in the Age of Postmodernism,” in Toni Stooss and Thomas Kellein, Nam June Paik: Video Time—Video Space, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), p. 80.

11 Paik, quoted in “Nam June Paik, Section 5: Electronic Nature,” Tate, online at www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/nam-june-paik/nam-june-paik-room-guide/nam-june-paik-section-5 (accessed March 2018).

12 Tomkins, “Profiles: Video Visionary.”

13 Dieter Ronte, “Nam June Paik’s Early Works in Vienna,” in Hanhardt, Nam June Paik, p. 73.

14 Ibid., pp. 73–76.

15 “Nam June Paik: 1932–1964,” in Hanhardt, Nam June Paik, p. 12.

16 Hanhardt, “Paik’s Video Sculpture,” p. 92.

17 Robert Rauschenberg, quoted in Sarah Roberts, “White Painting [three panel],” in Rauschenberg Research Project, July 2013, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, online at www.sfmoma.org/artwork/98.308.A-C/essay/white-painting-three-panel/ (accessed March 2018).

18 Paik, quoted in Hanhardt, Nam June Paik: The Late Style, exh. cat. (Hong Kong: Gagosian, 2015), p. 29.

19 Hanhardt, in ibid., p. 36.

20 Details of the work Lion were confirmed by Jon Huffman, Paik’s former studio manager, now curator of the Nam June Paik Estate, in an email to the author on January 18, 2018.

21 See Hanhardt, “Non-Fatal Strategies,” p. 79.

22 See Michelle Yun, “Nam June Paik: Evolution, Revolution, Resolution,” in Yun, Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot, exh. cat. (New York: Asia Society, 2014).

23 See Douglas C. McGill, “Art People,” New York Times, October 3, 1986. Available online at www.nytimes.com/1986/10/03/arts/art-people.html (accessed March 2018).

Artwork © Nam June Paik Estate