Brett Littman is the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, Long Island City. He has contributed news and commentary to a wide range of international art publications and critical essays to many exhibition catalogues. Photo: Don Stahl

Best known as a member of the musical trio Medeski Martin & Wood, Billy Martin is an American composer, percussionist, visual artist, educator, and record producer. He has worked in diverse musical contexts, from free improvisation to chamber compositions to film scores.

Marc Ribot, whom the New York Times describes as “a deceptively articulate artist who uses inarticulateness as an explosive device,” has released twenty-five albums under his own name over a forty-year career. He has collaborated with Tom Waits, The Lounge Lizards, Marianne Faithfull, Medeski Martin & Wood, The Black Keys, and many more. Photo: Barbara Rigon

Brett Littman I wanted to start off by asking you both what you’re listening to right now. I’ve been in this weird John Fahey, Takoma Records phase recently, listening to all of this American primitive guitar stuff. It’s been a real education to go through that whole discography.

Billy Martin I’ve been listening a lot to WFMU, a local station here. It’s been good because it’s turned me on to a lot of new music that I don’t know.

BL You’re in a discovery phase?

BM Yes, I’m kind of looking for new things to inspire me. I’ve also been heavily into Morton Feldman lately. I might be a little late to the Feldman party, it seems he’s kind of hip right now. Lastly, I’m into this rare record that I found by Jean Dubuffet called Musical Experiences. Did you know about that?

BL No, but that sounds amazing.

BM He made a record that explored all the sounds one could make with different instruments and other objects from a musically untrained and naive approach. It was made in 1963.

BL I remember driving around with you recently and listening to birdsong tapes. Are you still into those?

BM Absolutely. Those are the songs from Mexican birds that I picked up on cassette. They’re a big inspiration for me. Birdsongs are just endless variations on themes. I’m always looking for ideas and birds are always giving them to me!

Marc Ribot Ok, I was just looking at my iTunes, which turns out to be an archaeology of myself with dates added. It’s all there where the volcano buried it in lava.

BL A digital Pompeii.

MR Yes, my own digital Pompeii. So one thing I see is a lot of B.B. King on my playlist. I was recently teaching a class and wanted to find B.B. King tunes to illustrate my own personal history of how I came to play the way I do, and also explain the sense of economy in B.B.’s guitar playing.

BL Did you play them Live at the Regal? That’s one of my favorites.

MR No, what I wound up with was a compilation, Do the Boogie!. I found his version of “Dark Is the Night,” which I had never been aware of before, and a couple of other things with amazing solos by him. Hmm, I also see here a bunch of tunes with the word “Satan” in the title. I tend to listen topically and Satan has been on my mind lately. You haven’t really lived until you’ve heard the Louvin Brothers’ “Satan Is Real.”

BL There’s also that great Daniel Johnston tune, “Don’t Play Cards with Satan.”

MR Daniel Johnston, now there’s somebody very important. We can get into a whole visual-arts discussion about him because of his very disturbing drawings.

BL Well, there are a handful of musicians—Billy, you’re one of them—who also make visual art. Daniel was definitely very influential for me. I lived in San Antonio, Texas, in the early ’90s and went to visit him up in Austin a couple of times at his mother’s house. I used to mail-order his tapes with the drawings pasted onto the front of them in the late ’80s.

MR That’s right. I have a couple of his early cassettes . . . I treasure them. I think one of them is from before he understood the concept of mass production, he would just record the same songs over and over again so he could make new cassettes and give them to his friends—so each one was unique. Anyway, he’s a truly visionary artist. I aspire to being a visionary artist.

BL Billy, you had a couple of formative, strange, and maybe voyeuristic experiences with contemporary art early on. I remember you telling me that when you were living in Dumbo in the ’80s you looked out into Vito Acconci’s studio. Is that what started you making drawings and films and expressing yourself outside of a musical context?

BM Yes, it’s true—when I lived in Dumbo with my girlfriend at the time, who was always listening to Hans-Joachim Roedelius, the Clash, and Einstürzende Neubauten, I could look into Vito’s studio. But I was always fantasizing about visual art and music together in some way since I was a kid. I used to go hang out with my dad, who was a musician as well, and he would take me to these recording sessions where he would be doing movie scores for people like Ennio Morricone. I really wanted to do that. Later, I starting drawing with John Lurie in hotel rooms during the Lounge Lizards tours, and that continued while I toured with Medeski Martin & Wood and even to this day. The film stuff came later for me, when I finally got my hands on a 16-millimeter camera.

BL Billy, we’ve worked together a couple of times on art and music projects at the Drawing Center and at Sean Scully’s studio. Most recently, I curated your new set of graphic scores for a performance entitled Disappearing at the Herman House, your gallery/studio in the backyard of your house in Englewood, New Jersey. Can you talk about what you’re trying to do with these drawings and how they’ve evolved?

BM Simply, they’re just another chapter in exploring gestures through improvisation. In this case, the images sometimes inform my musical exploration and vice versa. This all led to my new percussion/prepared-piano solo release Disappearing, on my Amulet Records label. The record title highlights the journey into the unknown, which I find liberating and focused at the same time.

I really appreciate your curating that work for my premiere! We assembled some nice musical compositions together.

BL I don’t want to be overly nostalgic but I think the fluidity between music and art was tied to that very fertile time in New York in the ’80s and ’90s when the avant-garde/downtown music scene was really at its peak. You could go to so many clubs and hear people playing crazy things, and the crowds of people seemed so much more heterogeneous. Musicians, rockers, artists, drug dealers, performance artists, poets, and writers all seemed to be in the same room.

You have to get outside of music. We have to look at other things to find our voice and to share ideas. I look to artists, to other people expressing themselves in different mediums. I think it’s essential.

Billy Martin

BM Certainly that was true for me. If you were hanging out in the East Village and playing the Knitting Factory or CB’s Gallery, you were just running into everybody, and after a gig you might go over to someone’s studio to hang out to see what they were up to. Marc, I’m sure you were deep into that community and scene as well.

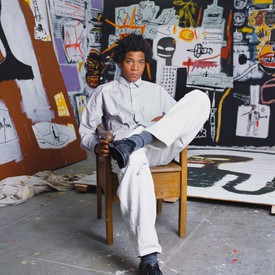

MR Jean-Michel Basquiat and Michael Stewart, talk about two very different kinds of artist, used to hang out backstage at the Lounge Lizards gigs. Not that I was a close personal friend of either, but that was who was around. It’s amazing what kind of community you could build when people could get apartments for $400 a month. Today you can’t find a place for under $2,500 a month. Suddenly everybody’s wondering, “Where did our wonderful heterogeneous utopia go?” Maybe we don’t hang out with artists anymore because everybody’s struggling so hard to try to make rent that they need to spend all their time hustling.

BL Marc, you’ve been pretty vocal about the need for more support of indigenous music scenes. There are empty buildings, there are places where collectives could be started and gigs could happen. I’ve surely seen a lot of these kinds of places in my travels in Scandinavia and in other places in Europe, particularly Berlin. It seems to me it’s not just about cheap real estate, it’s about what engenders a creative environment.

MR Well, one thing I want to make clear is that I’m not a fan of the Richard Florida “creative class” argument. If the market and subsidies don’t support experimental stuff, we need to make sure to keep it from becoming the plaything of the independently rich. That said, subsidies could be part of the mix as long as you avoid a nondynamic system where people are basically hiring their friends to play gigs and no one really gives a shit. European squats are a form of subsidy. Squats were interesting—a lot of them were centers of creativity because they had to present work that the local communities and the local press cared about and supported enough to show up and literally fight for.

Also, you have to say that behind those kinds of situations were the artists themselves, who were subsidized by rent stabilization and cheaper housing. The only reason I go into this, it’s not that I want to rant about it, but when we start talking about the ’80s as a golden age, well, if we want to be more than just nostalgic, let’s take a look at what went into making the heterogeneity, making the diversity, permitting the diversity and the hanging out—the real conditions that made possible a lot of what went on then.

BL You both teach a fair amount. What do you tell your students about studying music?

MR I’ve often thought that if I was going to write a guitar-method book, I wouldn’t call it How to Play Guitar, I’d call it Why Play Guitar. That’s the question we face, in common with all the other forms of arts. I’ve also tried to impress on younger guitarists the importance of being literate. Not only in terms of the other music: if you call yourself a guitarist, you need to have heard a range of guitarists, but you also need to have looked at other art forms and writing. I know I’ve gotten a lot from both.

BL Well, that’s good to hear. I think in the art world right now there’s too much specialization. Sometimes I feel that when I’m talking about poetry, writing, music, or film with people in the arts, I start to lose them. It’s kind of shocking because I don’t understand how you can be in the art world and not be interested in culture writ large. But maybe that’s just me. I’m a generalist.

BM Well, that’s the way you find out about new things and ideas. You have to get outside of music. We have to look at other things to find our voice and to share ideas. I look to artists, to other people expressing themselves in different mediums. I think it’s essential.

MR The other thing that’s important is translating. I’ve always been translating other instruments and other ideas with the guitar. I find the act of translation or mistranslation of Cuban big-band music, or Albert Ayler’s saxophone, on the guitar very productive.

BL Billy, I want to ask you about translation. You always bring a lot of different ways of making percussive sounds into everything you do. Do you view your role as a translator, or are you kind of a medium for all of this?

BM I don’t know, maybe closer to a medium. I’m probably more interested in misinterpreting something than in translating it straight up. I tell my students that if you’re going to play the drums, you have to widen your spectrum. Listen to a birdsong and try to play the phrasing. Is it possible to try to make your drum sound like a violin or a brass instrument? Think that out.

For some reason this conversation brings to mind the guitarist Derek Bailey, who for me is one of the biggest inspirations for creative musicians. Marc, I wanted to ask you what you think of Derek?

MR I’m a huge fan of Derek Bailey’s. I met him when I was in London and went to his house and jammed with him. It was funny, though, because at some point when we were jamming I tried to play what I thought was Derek Bailey–type music and he kind of instantly got bored and we started drinking beer instead. But later on, when we started playing some pieces of John Zorn’s and he was playing the role of the free improviser and I was playing these written jazz parts, he got very excited and he started talking about when he used to be a studio musician. It was really a very interesting interaction in the end.

BL Do you guys remember how you two first met? Was it through the Lounge Lizards or was it in some other configuration?

MR How did we first meet? Well, I think I met Chris Wood first—or did I meet all you guys at the same time?

BM All I remember is that Chris said, “Hey, this guy Marc Ribot called me to audition for the band. Who is he?” John Medeski and I were like, “Call that guy back. We have to play with Marc!”

MR Well, I remember that you guys had just come to town. I must have heard the band before I called Chris because I was really impressed with what you were doing. One of the main reasons I liked your music was that I love organ jazz, groove, and soul music and I thought, finally some people have gotten hip to this. When I was a kid in the suburbs around Newark, that’s what we heard late at night when we drove around. I was very happy to hear a group that was influenced by this genre and I was happy that you guys were focusing on groove. I remember walking by Chris and John’s loft down on Avenue A one day on my way to a rehearsal, and hearing you guys lost in this groove. A couple of hours later, when I was coming back after my rehearsal and a little lunch, you were playing the same groove. That was real dedication.

You know, my first big gig was touring with the great organ player Brother Jack McDuff at places like Sparky’s and the Key Club. The funny thing was that Brother Jack really detested my style of playing—but that didn’t stop me from having a long-lasting affection for that kind of music.

BL You’ve both done a lot of work with music and film. What’s interesting about putting those mediums together?

BM Well, for me it’s a very contentious relationship, a constant battle.

MR You get in fights with the directors?

BM Exactly. Marc, I’m sure you know a thing or two about that.

MR Well, I get in fights with everybody! It doesn’t matter if they’re the director or not.

BM I love music so much, and music creates so much visual and emotional content for me, but when I see an image associated with certain music, it often pulls it in another direction and often that’s not the direction I want to go in. But when music and image come together perfectly it’s the most beautiful alchemy you could ever experience.

BL Is there a particular section of a film with a score that for you is the perfect merger of music and image?

BM To be honest with you, this is really probably the opposite of what you’re asking me—but Satyajit Ray’s early film Pather Panchali has Ravi Shankar playing some incidental East Indian folkloric music. I don’t know why, but the experience was unique for me and I felt I was there. So that worked really well.

MR What’s interesting is, I think most people, if they’re being honest, wouldn’t be able to answer that question. They wouldn’t be able to answer it for the simple reason that when a film score works perfectly, you don’t hear it. I mean a real film score, not source music where someone sees a band playing in the film and you hear a band. I mean what you hear as underscoring—when it works perfectly, it disappears. I’m not sure there’s a visual-art corollary to that.

BL I think the soundtrack for [Paul Thomas Anderson’s film] There Will Be Blood, by Jonny Greenwood from Radiohead, is pretty amazing and really adds something to the visuals.

MR That movie goes against the phenomenon I’m talking about because the score is so much in the foreground. I’m much more of a traditionalist—I don’t want the score to be in the foreground, and when it is, I’m wondering why that’s the case. It’s nothing against any of the music in the film; I think Jonny Greenwood did a great job. He did the big percussive things, when people were galumphing through the fields and stuff, and it worked. But I’m more interested in scores that disappear. To me, that’s the art of cinematic music, and that’s what makes it interesting—when it points to a third dimension between the music and the visual.

BL Marc, can you give me an example of a film that you would say achieves that?

MR Almost anything that Alfred Hitchcock did that was scored by Bernard Herrmann. Certainly. It’s very strange and interesting to me, Billy, that you mentioned Satyajit Ray when trying to think of something that you had consciously enjoyed, as opposed to something where you said, “Wow, that music was interesting.” Indian cinema is one of the only film industries in the world that had its own origin and history really kind of outside the cultural influence of Hollywood. Because it’s outside of our own culture, we can hear it. The music doesn’t work for us in the same way that music that’s deeply inside our culture works for us. What’s inside our culture is invisible, in the same way that the power relations within our culture are invisible. You don’t see them as power relations. You see them as normal.

BL Billy, when you’re asked to do a score for a film, how do you approach that kind of work?

BM Every time, I start from zero. I try to have a conversation with the director or the producer and then end up ignoring most of what they said. I may have a little thing that I recorded, something on my iPhone, some mistake I made on the piano or some sound that happened. That may end up being the thing they love. Generally my philosophy is that I want to add something to a film, or try not to get in its way.

Recently, though, I worked with the director Yoshifumi Tsubota on the score for his film The Shell Collector. He basically sent me the first cut of the film, with no reference music and in Japanese. He wanted me to watch the movie and get a feel for it. Later we were talking about minimalist composers, Morton Feldman, and chamber music, and all of a sudden the sounds for the film came together for me.

MR Well, God bless you for starting from zero every time. I used to develop my own ideas and then fight with the directors forever about the music. But now I just say, “Okay, I’m a complete prostitute about it, send me your temp score and I’ll write stuff that sounds like it.” This is terrible. I have to say honestly that this discussion on film scoring almost doesn’t belong within this conversation about music and art. For me it’s like if a lawyer bought a gallery and insisted on going into the studio of every artist who was represented and said, “I don’t like red. Take a little red out of that painting. No, that one looks like a dog to me. I don’t like dogs. I want a cat.”

I do love working with some filmmakers though—like Jen Reeves. She’s brilliant and for some reason we always get along and we can work together very well. Other than that, though, you may notice that I’ve been generally scoring films by directors who died at least twenty years ago.