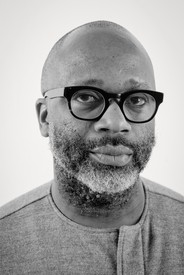

Sir David Adjaye OBE is a Ghanaian-British architect who has received international acclaim. In 2000, he founded Adjaye Associates, which today maintains studios in Accra, London, and New York and runs projects spanning the globe. Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents, Adjaye has established himself as an architect with an artist’s sensibility and vision. He is known for his ingenious use of materials and his sculptural ability and his influences range from contemporary art, music, and science to African art forms and the life of cities. His projects range from private houses, bespoke furniture collections, product design, exhibitions, and temporary pavilions to arts centers, civic buildings, and master plans.

Thelma Golden is Director and Chief Curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, the world’s leading institution devoted to visual art by artists of African descent. Golden began her career as a Studio Museum intern in 1987. In 1988 she joined the Whitney Museum of American Art, where she launched her influential curatorial practice. In 2000 Golden returned to the Studio Museum as Deputy Director for Exhibitions and Programs, working closely with Director Lowery Stokes Sims. She succeeded Dr. Sims as Director in 2005. Under her leadership, the Studio Museum has gained increased renown as a global leader in the exhibition of contemporary art, a center for innovative education, and a cultural anchor in the Harlem community. Photo: Scott Rudd

Mark Francis Thelma and David, you are working together on the development of the new Studio Museum building in Harlem. How did these plans come about?

Thelma Golden Well, this project began through a process that was initiated here at the Museum by our team, the staff, and the board as we began to think about the future of the Museum. Specifically, we began a study process of the building, thinking about the broad range of possibilities of what the Museum could be. Fast-forward a couple of years and we then engaged in a formal architectural search when we knew we had the possibility of actually constructing a new ground-up building on our current site. David presented a set of interconnected ideas that spoke deeply to our values, our vision, and our aspirations for what a new building for the Studio Museum could be. Is that how you remember it, David?

Sir David Adjaye Yes, exactly. I was really compelled to see if we could make a building which, being inspired by the Museum’s legacy of coming from the urban context of Harlem, would learn from Harlem rather than just bringing something from another place into Harlem. To go the other way around was really the thinking, and what I shared was the idea of a series of portals like the great perpendicular frames that are utilized all over Harlem.

MF I feel that the best architectural projects often evolve with a great client and a great architect working closely aligned and bringing different perceptions to a common goal. A famous example in the museum world, of course, is the Menil Collection in Houston, which is also very rooted in its site and location. I think more recently, the Prada Foundation in Milan is another example. How do you both, as architect and client, work together as a team?

TG While David and I certainly have a conversation, a dialogue, a space in which there are shared ideas, the real manifestation of this project—the ideas that informed it—were created out of the conversation between our teams. This is key to David’s design. I like to believe that some of what has made this project so meaningful, and already so resonant to people who see it and imagine it as our new home, is that it really is the result of this collaborative process.

MF David, sometimes these really collaborative projects take a long time, and that’s a plus, it seems to me.

DA Absolutely. I think that the best projects don’t happen very fast. They take time. They allow you to think deeply about the implications and the ramifications of the decisions made. Architecture is one of those art forms that benefit from time. We’ve been lucky enough to have ample time to think about all of the elements in this project. So it’s cooked, as we say in our business. Ready to go.

MF Thelma, the history of the Studio Museum, over a fifty-year period now, and its location here in Harlem are really fundamental to its mission today. How do you feel that your vision reflects the specificity of the institution?

TG I think what has always been important to my thinking about the institution, as I have led it over these last thirteen years, is to understand the intentionality of our name—quite specifically, the “Harlem” in our name and the idea that we are rooted here. So much of what I have thought about in relation to who we are has to do with the unique possibilities of site specificity. And that has also been informative in my thinking about the building project—not only did I want it to be site specific, but also site suggestive and deeply site sensitive. Ultimately, what David has created for us is site significant as well. I think place has always informed what the Museum is, and will continue to be at the core of how we understand ourselves.

what has always been important to my thinking about the institution . . . is to understand the intentionality of our name—quite specifically, the “Harlem” in our name and the idea that we are rooted here.

Thelma Golden

MF David, your architectural practice is based in New York, in London, and in Ghana. Can you outline how this very international outlook is brought to bear on this particular project?

DA I think there’s a wonderful synergy in that the three continental plates are really the three areas of the dispersion of the African Diaspora. Thinking about critical black history and thinking about the emergence of art practice in those diasporas, and being able to work and have offices in those spaces, for me, is very specific and very empowering.

MF Both of you seem to establish especially close ties to artists. Thelma, you’re chief curator as well as director of the Studio Museum. David, you’ve built studios, houses, and installations with artists. Indeed, the Studio Museum name alone makes clear that artists-in-residence studio provision has been and is a key aspect of the Museum’s plans. This is exemplary and perhaps unique in New York City. Can you each say something about the role of artists at the Museum and, if possible, in society more widely?

DA For me, the fact that the artist’s studio is very much the heart of the Studio Museum’s uniqueness, in terms of the incubation that it creates yearly, was a deep inspiration. In designing the new building for 125th Street, education space and the space for artists’ studios are presented as a sort of triptych frame that holds the center body of the composition. You have the public entry and then you have center composition, which is comprised of these two worlds of education and the artist and, importantly, where they meet.

Artists have been central in terms of my journey as a maker in the world. My first works were commissioned for artists. Artists are critical thinkers who allow us to have a very important view about the world we live in and the reactions that we have to it. For me, a critical part of being a creative person in the world is to collaborate with artists and thinkers.

TG The “Studio” in our name comes from the fact that, from the very beginning, the Museum understood itself to be a place with artists at its center—a place where the process of making art and presenting art would come together, and the artists themselves would have a relationship to the institution and to audience in a unique way by having the residency in the building.

David has done brilliant work with artists—homes, studios, exhibition designs. The spaces he creates house body, mind, and soul as well as facilitate creative expression. This was also something that was important to think about in this building.

As an institution, we have historically lived in adapted-reuse spaces. Neither our first space on 5th Avenue between 125th and 126th Street nor our current building was originally made to be a museum. But the Museum’s spirit was always to populate those spaces with art and artists and audiences in ways that demanded an organization created out of imagination, will, creativity, innovative spirit, and a radical vision of what a museum could be. In moving towards this incredibly beautiful, purpose-built space, one thing we didn’t want to lose was what it meant to have that feeling of a space that was informed by art and artists.

One of the great gifts of working on this project with David was the fact that we had spent so much time looking at art together. Looking at art with David and having his perspective on architecture and space certainly informed the dialogues that we had around the design. Many of the artists that David has worked with architecturally, I’ve worked with curatorially. And so we have these very different but, in some ways, complementary relationships to understanding their practices.

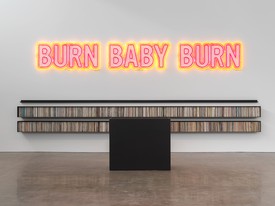

One of the most productive conversations we have had has been with Theaster Gates. My conversations with Theaster were incredibly influential in my thinking about this idea of a reinvention of our space. Those were conversations I was having with him as an artist, yes, but also as someone who has been doing the work—the hard work, the radical work, and the deeply transformative work around space-making, community, and notions of place. And I know that David and Theaster have had their own set of similarly generative conversations.

DA Yes, I’ve had a deep relationship with Theaster for a very long time. I consider him a dear friend. His attitude to the way in which you reconfigure the urban context has been a very important ongoing conversation for me. As we’ve been working on this project, these kinds of conversations have been very critical in fine-tuning my thinking about how to make this building work within its context and connect with history and to its potential future.

TG Exactly. His ability as an artist to understand these different phases of what we have been doing has been really rich and incredibly helpful, especially as we think beyond just the surface of an architectural project.

MF The new building will have very public access to 125th Street and a wonderful open auditorium space used for debates, screenings, performances, and so on. The building, as a whole, serves very flexible uses and seems to have a very dynamic and welcoming feel for audiences. How would you say the future program is articulated in the building’s different spaces?

TG We intend to broaden and deepen our program. To still be committed, as we have been, to the presentation and interpretation of work by artists of African descent and work inspired by black culture, but to do so in ways now that are incredibly dynamic—that possibility is made real for us through this building. As this museum has been throughout its history, we will remain open and responsive to our artist community, our location, and to the museum world as a whole, which is in a moment of major transformation as we think about our relationships to audiences and how we present works of art.

I was really compelled to see if we could make a building which, being inspired by the Museum’s legacy of coming from the urban context of Harlem, would learn from Harlem rather than just bringing something from another place.

Sir David Adjaye

MF The Museum has a very clearly defined local and national role in the city, but it also seems to have a very cosmopolitan and international outlook. Could you articulate how this serves audiences locally, nationally, and internationally?

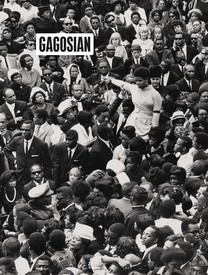

TG I think that perception of who we are is a reflection of some founding principles of the Museum, but also of this community and of this culture. Harlem has always been an incredible international and cosmopolitan neighborhood that has seen itself rooted very locally. But also, for many, when we talk about Harlem and particularly the Harlem Renaissance, which is arguably one of the greatest moments of modernist history, it also is a moment when we understand Harlem as a psychic and spiritual home of black culture broadly connected to the ways in which the culture exists around the world. We have always lived with this: a deeply rooted local existence, and also a wide reach.

MF Outside of the museum context, what is your favorite place in Harlem?

TG I would say, rather than a favorite place in Harlem, that this project has deepened my love for this community in all of its complexity. The way it both lives in its past—in the historic sensibility that you feel on these streets—but also articulates, in so many different ways, a future. I think Harlem is one of those communities that evidences itself in public. You feel it walking through the streets. You have a sense of what it is.

DA I think that there’s something very powerful about the way in which the communities have reused the architecture of Harlem and made it their own. To inherit a stock and then turn it into a specific narrative that reflects the character of the communities is beyond inspiring. Like the stoop culture, which is incredible in Harlem. You see mothers and grandparents and young kids on the stoops. You go to the churches or you go to the incredible theaters, both the more formal ones and the informal ones. Or the happenings that happen in shop fronts on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard or anywhere else, where suddenly a gig might happen or a talk is happening and it engages with the street. These are really powerful experiences that are unique to what, on first glance, may appear like a typical city. There is actually this hybridized, specific cultural expression when you get to engage with it further, and that’s a very powerful thing.

Building renderings: courtesy Adjaye Associates