Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

A white hand, black with soot, clamps open and shut. It lets pieces of lead fall through its gnawing fingers. Sometimes it catches the pieces, sometimes not. It always allows the lead to leave below the frame. The body is framed as a fragment, the hand floats. It would seem there is no end result to all this hand-grasping: as soon as a lead is caught, it is let go. Process is the central point of interest, and three minutes later this short film meets its end in a peter-out as sudden as its start. The film extends the “termite-art” tradition championed by the painter-critic Manny Farber in 1962, in which there is “buglike immersion in a small area without point or aim, and, over all, concentration on nailing down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgetting this accomplishment as soon as it has passed.”1 The film’s title is just as unflashy and to the point: Hand Catching Lead (1968). It suggests that the tasks on display could theoretically extend to infinity, but then this action-with-a-lowercase-“a” film would lose the crucial material that gives it its form and its definite endpoint: that mysterious, human element of plain tiredness.

For eleven years (1968–79) Serra felt out the uncharted phenomenological boundaries of film, pushing it to exciting heights in line with the watershed period in cinema history out of which his moving-image work sprung. Hand Catching Lead was made less than a year after the appearance of the Canadian artist and filmmaker Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), a landmark event that, as Annette Michelson pointed out, “came at a time in the history of the American avant-garde when the assertive editing, superimposition, the insistence on the presence of the film maker behind the moving, hand-held instrument, the resulting disjunctive, gestural facture had conduced to destroy that spatio-temporal continuity which had sustained narrative convention.”2 No longer were film’s unique qualities and effects chained to the flourishes of plot or psychological identification with the action and figures on-screen. Snow announced a visionary way of sensing-through-film that no one else in the medium had been able to articulate so forcefully yet coolly. As Serra said, “Wavelength was the most interesting thing that was happening [in film],”3 and the “aspect of unpretentious, indigenous American poetry that was difficult to deny”4 in Snow’s and others’ work (Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls and Yvonne Rainer’s Hand Movie, both of 1966) encouraged Serra to pick up the camera and use it as a device in a series of remarkable studies of moving-image perception: the hand films he made for Leo Castelli’s gallery; a Snow-type work in a New York loft in which a seemingly rectangular window is revealed to be a trapezoid (Frame, 1969); ideology-revealing videos in which he parodied and “expose[d] the structure of commercial television”;5 certain process films that burrow deep into the lives of bridges or of factories that have pulverized the ears and souls of men for untold generations. Serra’s films work in the tradition of “unpretentious, indigenous American poetry” that he sees in areas such as Jackson Pollock’s paintings, Snow’s Back and Forth (1969), and “those bridges [that] were built during a ten- or twelve-year period [between 1905–06 and 1925] for efficiency and support and nothing else.”6

Most of Serra’s early film work focuses on tasks in short bursts: a hand catches lead, two hands untie themselves from a rope bind, two pairs of hands pick up lead filings, Tina turns. The length of time it takes to complete a task is based on elements that are hard to quantify but solid enough that one can expect an endpoint (two or three minutes): the hand will stop when it gets tired, Tina Girouard will spin until she’s dizzy. Serra’s early work wasn’t shown in a traditional theatrical setting such as Anthology Film Archives—New York’s church of film, which, in its early years, had built-in “cabins with side panels aimed to maximize optical and acoustic focus on the screen”—but in the then new Leo Castelli Gallery at 420 West Broadway, in a loft of 740 square meters divided into three exhibition areas, with a separate space for film and video screenings.7 On September 25, 1971, Hand Catching Lead, Frame, Hands Scraping (1968), and Tina Turning (1969) were screened at the Castelli Gallery as part of a show that included sixteen works on 16mm film by Serra and his contemporaries Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, and Keith Sonnier. The viewer was placed in “an environment where the projected image was presented in a more open way that both activated and distracted the viewer’s body,” the films being screened simultaneously around the space “with no fixed choreography, their visual and auditory combinations unplanned, left to chance.”8

The presentation of Serra’s films in such a setting is important to establish, but only insofar as it highlights the unique bodily demands they made on viewers who first encountered them. In the past—usually at the expense of what occurs in the films—some critics have tried to link the experience, material concerns, or aesthetic boundaries of these works to those of Serra’s best-known practice, sculpting. Serra himself has been adamant in his hostility toward such connections: “I did not extend sculptural problems into film or video. I began to make sculptures, film, and video at about the same time, so it can’t be a question of developing one form into the other. My involvement with different media is based on the recognition of the different material capacities and it is nonsense to think that film or video can be sculptural.”9

Serra’s films and videos constantly call attention to themselves as films, but always with the political and the artistic on nearby parallel tracks—that is to say, never esoterically. Perhaps the ones that most demand our attention today are Anxious Automation (1971) and Television Delivers People (1973). The former works in the territory of Hand Catching Lead: we’re made aware of the hundreds of still images that come together to form an illusion of a whole filmed subject (though video has a synthetic, blurry grunge that even 16mm resists). A languid Joan Jonas sits on a sofa. She makes throwaway, bored gestures with her arms, cocking her elbows at bizarre angles. Two cameras are trained on Jonas, and they switch off every other second, creating a sense of the space around Jonas collapsing in a chaotic but consistent jumble. The cuts—more aggressive and space-splitting than anything in a mid-’70s Ken Russell sequence—never let you linger or dwell, the zone of most of the Serra films. It’s a video whose playfulness contributes to the bitter point: it relies on an oblique, deadpan humor to mock the synthetic techniques that Hollywood uses to keep the viewer’s attention span short, to degrade space, to depict time as a grotesquely foreshortened linear stream. It’s a parody of MTV avant la lettre. Serra does in termite-sized short form what the British director Peter Watkins (La Commune (Paris 1871), 2000; Strindberg 1849–1912: The Freethinker, 1994) does in symphonic swaths: he finds a way out of what Watkins calls the “Monoform,” that “repetitive TV language-form of rapidly edited and fragmented images accompanied by a dense bombardment of sound, all held together by the classical narrative structure.” Serra and Watkins rebel against a wall-to-wall mass media schema that “gives no time for interaction, reflection or questioning.”10

Serra’s films and videos constantly call attention to themselves as films, but always with the political and the artistic on nearby parallel tracks—that is to say, never esoterically.

Serra’s jabs at mass-media find their peak in Television Delivers People (1973; made in collaboration with Carlota Fay Schoolman), a six-minute tape where what’s being brashly exposed is the gullibility of a populace that doesn’t realize it’s being sold up the creek as the shiny object of a diseased capitalism. The cagey humor comes in the inspired offsetting of a dead serious scrolling text (“Popular entertainment is basically propaganda for the status quo”) with mind-numbingly cheery Muzak. Serra’s intellect here is brutal, cutting. Just as the Hollywood film director Frank Tashlin vented his withering love-hate relationship with American pop culture through the very medium that propped it, and him, up, Serra needed to bring TV’s rotted, invisible ideology back home to roost. So he and Schoolman arranged to have the tape aired on broadcast television—first in Amarillo, Texas, as a brief sign-off to regular programming (1973), then in Chicago on WTTW (1979). (“It received newspaper reviews the next day, which made me very happy.”)11 Serra mentions that the tape has a touch of Jean-Luc Godard, in the French director’s didactic Dziga Vertov mode (Godard was also one of the earliest proponents of Tashlin’s barbed satire in the 1950s), and indeed there is, as in Godard’s Vladimir and Rosa (1971), an elegant and unfussy dialectic between the image and the idea, between pared-down text in yellow on blue and the concretely abstract ideas it’s exposing in real time.12 Serra’s ideas are not concealed in the tape; they are rudely visible, working to jolt viewers out of their drugged “Everything is Awesome” state and into mental action. The tape hinges on a disturbing resituation of the word “deliver,” the subversive proposal that we are not the recipients of the products we use but, rather, the passive beings traded off by those same products (and their makers). “In commercial broadcasting, the viewer pays for the privilege of having himself sold,” it tells us. Much of Serra’s and Schoolman’s ideas haven’t changed in the digital era, when sites like Facebook, Amazon, and Google track our every search—who we’re friends with, what music we listen to, which Ike or Mike we like—in order to best tailor their nonsentient products (Alexa) to their sentient ones. “In America,” Serra said in 1973, “probably one of the few things that people can believe in is entertainment. If you give definitions, political, economic, whatever, through entertainment, people believe them; I don’t know why.”13

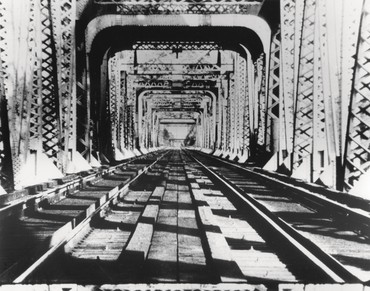

In the two Serra films of the late 1970s, the brash, murderous, expose-the-bastards drive of the videos is mixed with the earlier process films’ need to stick with a task-object-setting over a hypnotic, Warholian stretch of time. 1976’s Railroad Turnbridge (“there was really a need to investigate what ‘bridgeness’ meant to me”) grants the titular structure a touching cement-footprint presence by squaring all sides of its existence.14 It ennobles, without phlegmatic nostalgia, a structure that people usually ignore because its entire function is predicated on inconspicuousness. Presenting a turnbridge over the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon, Serra’s camera halves, twists, bisects, and frames the bridge in such a way as to make birds, cars, and freeways seem to pass impossibly and cleanly through its center. The turnbridge is a sturdy entity that doesn’t call attention to itself, doing its job of supporting heavy vehicles and no more. Serra captures it as it turns; his shots don’t explain how the bridge literally bridges, since he’s more concerned with evoking the sensation of bridging—the meeting of two points—and with all the by-details that give the connection-event a solidity and a presence in the physical world. What sticks in the mind is a shot of a patch of still rail as a train whizzes across it—the quietly buzzing rail barely noticing the whirling kinetic energy coursing through its steel. The turnbridge columns crumple like an accordion. As the bridge turns, the camera remains planted, so that it looks as if the sky and the horizon (an illusion within the illusion) are moving, not the bridge. A train crosses the railroad span and nears our eye, in the style of the Lumière brothers’ film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895). In the bridge film, something of the primitive purity of vision is restored, a vision lost in the early twentieth century when people and filmmakers turned toward D. W. Griffith’s narrative whirligigs and away from the raw, tough, premontage act of Lumière looking.

A few years later, Serra and the art historian Clara Weyergraf made Steelmill/Stahlwerk (1979), probably the least sentimental workers’ film in existence. Ostensibly detailing “working conditions in a German steel mill,”15 this is a funky, undeclamatory work in which art, commerce, and labor are harmonized by a rigorously assured composer’s eye rarely seen since 1955, when Jay Leyda compiled the rushes for Sergei Eisenstein’s unrealized ¡Que Viva México! (1930). The twenty-nine-minute, 16mm film is divided into two halves: one in which Weyergraf interviews a group of anonymous German factory-workers about their conditions and one in which Serra’s camera tracks through the space of a steel mill where an object (Serra’s sculpture Berlin Block [for Charlie Chaplin], though its identity is never made explicit) is being forged. There’s again the focus on the fragment that defines Serra’s film practice: never give the viewer the whole factory, don’t have the sensitive, thoughtful, talking laborer and the silent, efficient, machinelike laborer in the same body or frame. The men and their labor symbolically exist in Steelmill either as text—disembodied voices—or (in one unforgettable shot on the level of Chantal Akerman) as the forearm of a foreman that pulls a lever back and forth and back and forth.

The film’s first half—Weyergraf’s questions in German, the workers’ answers in German with white English-language subtitles against a black screen—evens out all the responses (only her voice is distinguished) to create an allover collage of experience, hewing as close to the truth of a situation as one possibly can in montage-based film. “If I had more money, I’d spend it on my hobby: gardening and rabbit-breeding.” “Well, what is freedom exactly? Freedom would be there only if I had enough money to live freely. Whether I’d be free then, I don’t know.” There’s a brute matter-of-factness to the workers’ responses that transfers over to the second half, in which Serra wields the camera around the factory and radically respects the space à la Akerman or Warhol. Garbled German orders sometimes fly out of the din of the factory, but otherwise the soundtrack is dominated by a harsh buzzsaw/flametorch drone—the punishing sounds that render the workers nearly deaf. Though it’s clear that the filmmakers are gravely concerned for the day-to-day grind of these laborers, this concern isn’t spelled out in hectoring, pity-please tones—a restraint made apparent by the film’s lack of Soviet-type cutting into the space, no voiceover, no factoids about the Ruhr Valley mill. It has the look of a documentary, but little context is given to sway us into feeling one way or another about these images. This was an intentional effect: in his 1979 interview with Michelson, Serra noted that “if a film is made about [workers], there is a narration explaining to the class that is in the film what they are doing in a way that is beneficial to the union, or the administration, or the power that is funding the film. So most documentaries flagrantly support the status quo, thereby keeping the worker oppressed, or they function as advertisements for the class that wants to sell the products to the class that is dying making them.”16

What distinguishes Railroad Turnbridge and Steelmill is their remarkable historical consciousness. Yve-Alain Bois has written on Serra’s St. John’s Rotary Arc sculpture (1980) that “one has only to reread the pages Serra has written on Rotary Arc to be convinced that film fragmentation is an apt metaphor with which to describe his work”17 —an interesting observation when one realizes that Serra’s films crawl along in the exact opposite direction: blocks of long takes at odds with the Vertov–Eisenstein–Alexander Dovzhenko rush. The films have Eisenstein in their DNA (Snow is most present), but it’s the Eisenstein of the unfinished ¡Que Viva Mexico!, in which the frenetic montage that links history, art, politics, and philosophy occurs inside the viewer’s head, incorporating her range of experiences, his mental montages. The work thus becomes collaborative and open in a way that defies the typical process of presenting movies to viewers—tossed or flung at us, forcing us to engage with a drab, bullying, closed Monoform system that condescends to our intelligence.

1Manny Farber, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art,” 1962, in Farber, Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies, 1971 (reprint ed. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998), p. 144.

2Annette Michelson, “Toward Snow,” Artforum, Summer 1971, repr. in Michelson, On the Eve of the Future: Selected Writings on Film (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), p. 174.

3Richard Serra, in Michelson, “The Films of Richard Serra: An Interview,” with Clara Weyergraf, 1979, in Serra, Richard Serra: Writings/Interviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p. 63.

4Ibid., p. 62.

5Serra, “Prisoner’s Dilemma: Interview by Liza Bear,” 1974, in Serra, Richard Serra: Writings/Interviews, p. 20.

6Serra, in Michelson, “The Films of Richard Serra,” p. 69.

7Tom Holert, “The Task Is the Task,” in Manual No. 7: Richard Serra Films and Video Tapes, 20 Mai—15 Oktober 2017 (Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel, 2017), p. 11.

8Ibid.

9Serra, in “Interview: Bernard Lamarche-Vadel,” 1980, in Serra, Richard Serra: Writings/Interviews, p. 116.

10Peter Watkins, “Notes on the Media Crisis,” 2010. Available online at www.ocec.eu/cinemacomparativecinema/index.php/en/11-materiales-web/387-notes-on-the-media-crisis (accessed July 16, 2019).

11Serra, in Michelson, “The Films of Richard Serra,” p. 74.

12Serra, in “Prisoner’s Dilemma,” p. 20.

13Ibid., p. 21.

14Serra, in Michelson, “The Films of Richard Serra,” p. 69.

15See Harriet F. Senie, The Tilted Arc Controversy: Dangerous Precedent? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), p. 65.

16Serra, in Michelson, “The Films of Richard Serra,” p. 79.

17Yve-Alain Bois, “A Picturesque Stroll Around Clara-Clara,” trans. John Shepley, 1984, in Hal Foster and Gordon Hughes, eds., Richard Serra (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), p. 88.

Artwork © 2019 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; films: courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York; stills: courtesy Richard Serra

Richard Serra: The Complete Films and Videos, a retrospective of the artist’s films and videos, will be shown at Anthology Film Archives, New York, October 17–23, 2019