Louise Neri has been a director at Gagosian since 2006, working with artists and developing exhibitions, editorial projects, and communications across the global platform. A former editor of Parkett magazine, she has authored and edited many books and articles on contemporary art. Beyond the exhibitions she has organized for Gagosian, she cocurated the 1997 Whitney Biennial and the 1998 São Paulo Bienal, among numerous international projects. Photo: Lin Lougheed

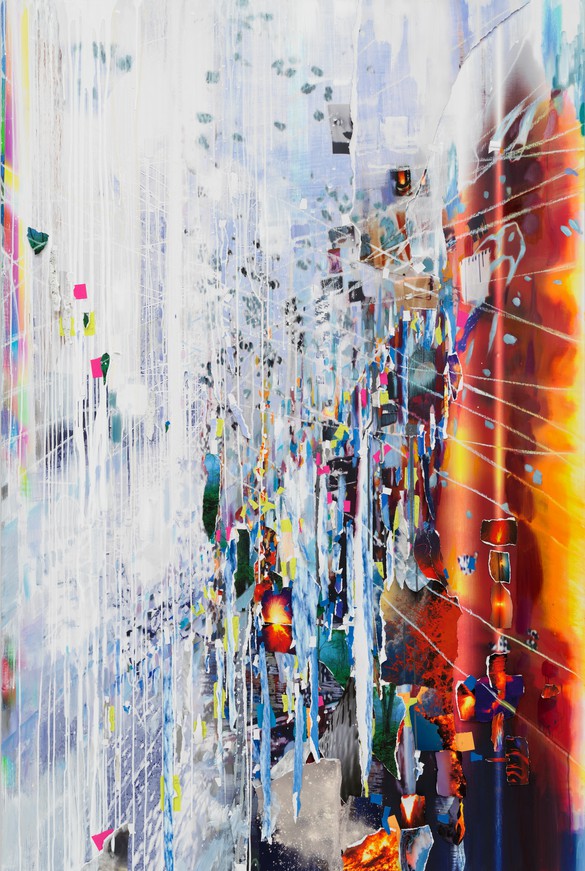

Sarah Sze’s art utilizes genres as generative frameworks, uniting intricate networks of objects and images across multiple dimensions in sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, and video installation. Her works prompt microscopic observation while evoking a macroscopic perspective on the infinite.

In the age of the image, a painting is a sculpture. A sculpture is a marker in time.

—Sarah Sze

Louise Neri In the context of a singular artistic practice where objects, space, time, and context have been your principal materials, why do images hold so much appeal for you now?

Sarah Sze I painted with oil from age nine to twenty-five, working from the live figure on the one hand and Josef Albers’s color theory on the other. I started with the image. Painting is the lens through which I came to approach sculpture in the ’90s.

LN Can you explain how?

SS From my study of painting I borrowed color, mark, and composition to inform my sculpture, as well as scale, circulation, and utility from architecture. What’s interesting now is that I can see the influence of painting and architecture through a more elusive and psychological lens. I see their influence on the content of the work—through painting’s engagement with intimacy, improvisation, and immediacy, and architecture’s play with memory, behavior, and narrative created over time.

LN So why did you stop painting in the first instance?

SS At that time I didn’t feel that I had a subject. Despite being academically trained, I didn’t know why I was doing it, other than for the joy and the absolute seduction of spending time in front of it.

LN So what changed?

SS I found my subject matter. Over the last year, I’ve been drawn to the way time works in painting, how every mark changes the entire equation. I’m finding incredible freedom in making paintings again.

LN Richard Serra once credited you with “changing the very potential of sculpture.” What do you think he meant by it? Would you say that your sculptural practice informed your return to painting?

SS In sculpture I found a language of entropy, dynamism, and instability, which remain central drives for me. Specifically, sculpture allowed me to address issues of gravity, mobility, site, seeing things in the round; how I could spill from the edge into the world in this very complex way that wasn’t bound by the frame. Now, in my new paintings I’m interested in how the world spills into the frame—and, to even take it a step further, how we confuse that frame with the world. With the incredible ubiquity of images, which has intensified over the past twenty years, images and objects have become conflated, layered, fused. How we are oriented and disoriented in the world is not just spatial; it’s increasingly influenced by the role and power of the image. I think in the age of the image, a painting is a sculpture. A sculpture is a marker in time.

LN The sculptures that constituted Triple Point, your exhibition for the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013, were described as models of uncertainty or instability; is this true of your paintings too?

SS All my work addresses uncertainty and instability, but the sculptures are more literal. They actively perform those ideas. In their very existence they play around with the idea of trying to embody concepts physically, and how an object can represent ideas in the form of a dynamic model or a tool of measurement. So I’m modeling uncertainty, live.

In two dimensions, this kind of modeling is employed with flat images that can be used as tools to measure, like the use of the blueprint in the permanent tiled mural for the 96th Street subway in Manhattan, or the eye chart and color-blindness test I use in silk screens; or an actual yardstick becoming part of the paintings for Rome—a kind of flat modeling that Jasper Johns does so elegantly, whether with a map, target, or silhouette.

Subsequently, this idea of locating oneself and falling apart again is very much what drives the new paintings. To find places in them that you can look at, and how that’s affected by the distance between the viewer and the painting. From far away it has a totally different quality; close up it falls apart. And that approach comes from making sculpture.

LN Did this approach also motivate your new stone sculpture?

SS The split stone sculpture opens like a cut in a geode to expose an interior image on each inner face. I was also thinking of the stones as tools to make images, like a potato print or a Chinese chop—a basic tool for imprinting an image using pressure and gravity, where the material processes of making images intersect with the forces of sculpture.

There are several scale shifts in this new work, from the presence of the weighty boulder to the fragility of the embedded colors in the smooth split surfaces and, finally, the vast landscape that the pixels come together, one by one, to depict. These scale shifts are active in space as the viewing range for the sculpture moves from far away to close up.

LN Most of your sculptures involve some degree of site sensitivity, where the contingent architecture becomes part of the whole. Do the paintings allow you to disengage from this problem?

SS I’m still interested in that problem, but not in the limitations of its attendant critical language. Paintings were once site specific; now they are seen as migrant in different ways. Five hundred years ago, Titian made his paintings for the Frari in Venice specifically for the church, fitting them snugly into the shapes of the architecture and reflecting the columns of the space perspectivally in the space of the painting itself. So to talk about “site specificity” or “site sensitivity” as being tied to any specific medium is more a semantic limitation of twentieth-century thinking and discourse than anything else.

What interests me about paintings now is that they are extremely mobile and site specific: they are themselves wherever they go. When I began making sculptures, it was with the idea of the kiosk in mind. I was always drawn to Russian Constructivism, in art, architecture, and philosophy, and to its idea of the kiosk as a small architectural structure that you could fold down and bring to public space, indoors or outdoors. To set up a station of information was a model for me for making sculpture. My sculptures often model larger systems but are sometimes small and portable, sometimes literally on wheels, lit from below; they feel like kits that can be put together on the ground.

LN In fact, they really are kits, they can be dismantled and reconstructed according to a precise manual.

SS And because they look mobile, they look right anywhere they go, the way cardboard boxes do. Paintings are the same; they contextualize themselves among other things wherever they end up. So if you think about it, a white-cube gallery exhibition of paintings is a strange idea, because ultimately they’re going to end up elsewhere and in other company.

LN It’s a temporary herding.

SS Exactly. Paintings have this way of remaining themselves in the world; like books and letters, each of them is a complete story.

LN Given all this, would you say that your approach to both mediums is converging?

SS Robert Rauschenberg said, “You begin with the possibilities of the material,” and I’m interested in asking what a painting can do that a sculpture can’t, and vice versa, but essentially I approach making a sculpture and making a painting in the same way. I think of a painting as a sculpture and a site. In the most traditional form of painting you start with a gestural underpainting, an overall composition on a canvas. This is how I first imagine my sculptures, in broad strokes in space that then funnel down into detail—maybe like the last mark in a portrait painting could be the stroke of light in the eye with a single-hair brush.

LN Before moving on, can we touch on the evident impact of Rauschenberg's process-driven, combinative approach to image-making on your own practice?

SS Specifically, Rauschenberg was able to utilize the language of a single medium while moving fluidly among several at the same time, resulting in newly hybridized art forms that resisted generic definitions. Modern image production has allowed me to intensify this approach; I use genres and mediums simply as frames to generate endless possibilities, rather than as ends in themselves.

Every mark in a painting is a part to a whole, and each part is defined by an edge—soft, hard, fast, slow, or tonally hot or cold. Similarly in video or sculpture I’m always thinking about the transition between things. The idea that meaning is created in the moment of transition is a classic filmic idea, but it belongs to painting and sculpture too, intimately, simply in how you position any one color or gesture or object at the edge of the next. There’s a delicate equilibrium in those transitions and relationships, a fragile tension that exists across all mediums.

LN You often cite your firsthand experience of Japanese gardens as an influence on the way you organize a sculptural installation—the idea that there would be a subtle visual parcours to draw one’s attention to things along the way, and to encourage the exercising of one’s powers of perceiving different kinds of perspective and shifts in scale. Is the same true of the paintings?

SS I think a painting has the capacity to throw the viewer into an imaginary space. It may be flat and dumb, and you’re not supposed to touch it—it’s not a film with magic and light and narrative—and yet you will take it and run with it. In my paintings, a gray area can take you into an almost cosmic space, and whenever that scale shift happens it reminds you of just how much work the eye and the imagination do. In this way one could say that while a sculpture occupies space, a painting can create it. Images are different; they propose a portal for you to slip into. In both the three-dimensional and the two-dimensional work, I’m interested in trying to keep you just on the edge of that slippage in scale, so that while you’re slipping, you’re aware of the slip, rather than being completely sucked into it.

LN How has photography affected your recent painting?

SS What’s interesting about a photograph is that our eye is told what’s in focus and what’s out of focus, which is not how we actually see. With a painting the eye is often trying to rectify and deal with light and color and materiality at all times. But I would hazard to say that today there are few painters who aren’t using photography as a tool in some way. For example, I think there’s a lot of ground that people haven’t picked up on from Gerhard Richter about memory, photography, and painting. The works that are interesting to me are the photographs that he dips into paint, that simple gesture in time, and the physicality of the photograph with the paint right on top, that rawness and tactility.

LN What, then, is the significance of the torn photographic image, which is both the image and the subject of your new collaged and painted works?

SS To tear an image reminds you that it’s printed on paper, and that the typical squareness of a sheet of paper is as artificial as the rip. So the illusion becomes interrupted by an edge, which reminds you that the image is not so different to an object.

LN And as vulnerable.

SS Yes, vulnerable in the process of being exposed to time. The rip is a moment in time that is difficult, perhaps impossible, to re-create. We know how to cut a square of paper and repeat that process endlessly, but the rip is an impulsive, unique moment.

The illusion that the image provides of being broken, interrupted, is important; so my paintings are as much about behavior as materials. I wanted to locate the rawness of time and improvisatory quality that painting possesses, but by employing sculptural strategies.

LN In your sculptures, you work with the inherent properties and taxonomies of objects; there is an evident order of things. How does this correlate to painting?

SS Painting is different now, in the context of the glut of images we live in. I think there now exists a taxonomy of images high, low, found, created, pixelated, clipped, shot, personal, public. We trade them like objects. A crafted image is now a rare commodity in the constant onslaught of random images. Perhaps that’s what holds painting’s appeal, for the maker and the viewer.

LN You recently published an article in the New Yorker about your Timekeeper video-installation series, describing it as a resistant gesture to “recover our sense of time through tactility.” Can you elaborate?

SS Take, for example, when our generation was growing up, I don’t think we were really aware that the television would become obsolete so quickly, whereas now we know from the moment we purchase a new mobile phone that we’ll soon need another one. This new reality, this sense of the speed of the turnaround of technology, coupled with our dependency upon it, is very intense, inferring a huge loss of the physicality of time.

LN In what sense do you understand “the physicality of time”?

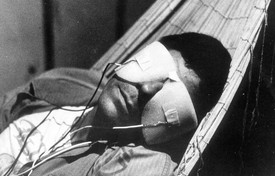

SS If, say, you considered time in bands, how wide would any one band be? I think that the ways in which images are being experienced now is close to early film and photography. The Timekeeper series reflects on our return to a filmic way of seeing images, in succession, in multiples, at random, scrolling through them over time. The still image itself is dying: we hold a button down on our iPhone by mistake and record a “live” image. We look at images and take them in streams, in rapid succession. Look at the very beginnings of film, say, with Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey and, later, Harold Edgerton: how they saw things filmically, but in a photographically scientific way, producing visual tools with which to understand reality. So this process allows me to go back and consider how the photograph has become a primary tool of communication, one that’s replacing written language at a surprising rate.

LN You edit from an endless supply of made and received images, which don’t seem to have any real hierarchy in terms of importance. How do you select them?

SS The palette of images is in constant flux, being added to and taken away from. They all are moments when your sense of time seems to slow or speed or be marked in time somehow, like the landing of a plane or the explosion of a kernel of corn as it pops. They also often describe very material, tactile processes, like water dripping, fire burning, structures collapsing. But often the most memorable, I think, are quite idiosyncratic. The burning pot, for example, is a total fluke. I burned some popcorn while making it and threw it out onto the grass to avoid burning the house down, and then saw it circling in the pot because of the wind, pulled out my iPhone and filmed it. When you see it, you can’t understand or explain it. The videos of my daughters running around the pyramids of Giza and sleeping were totally spontaneous. The video “snow” creates a sort of visual hum and indicates a sort of absence or malfunction—the death of the image itself, even.

LN So how do you maintain the tension between the poignant and the dispassionate, the personal and the archetypal, in these images?

SS One of the first sculptures I made at graduate school was right after my grandfather died. To see how he dealt with possessions, what really mattered at his stage in life, affected the way I made sculpture: What did he keep? What didn’t he keep? Usually what was kept had to do with value in terms of a memory, as a retainer of experience. So it’s interesting for me to consider what’s retained over time—which artworks stay with you, and how do they burn into your memory? My goal is to create a state where you’re seduced by the workings of film, but at the same time uncertain—and then the rug is just partly pulled out from under you. One foot on the ground, one foot on the rug. You’re not involved in a classic cinema experience where you can give up uncertainty. You’re alert. It’s an editing model for how I strive to create a locus that’s teetering between two things. So every time you find your bearings in my sculpture or my video installation or my painting, you’re just as quickly disoriented, and your experience teeters back and forth between finding footing and losing it.

LN Eating one’s own trail of breadcrumbs, so to speak.

SS And you know you’re eating them! You’re asleep and awake. You’re in the state of the imagined and the image itself. The pictured and the picture. You’re in it but still outside of it enough to question why I chose this or that image.

LN Why is this state of teetering so important for you?

SS Breakdown. All of my decisions are about time and its breakdown, whether the inevitable breaking down of the image, digital breakdown, the way light hits water or paint is dragged across a surface. My edits all convey a sense of time. They’re all one-minute loops and each loop has a kind of dying out in that they pixelate or break apart, so that you can observe the image in the process of self-destruction. This is partly to remind that the image itself possesses material qualities—there’s a machine behind it, it’s light on paper and the paper is moving. And importantly, all the loops are deliberately not synced; the juxtapositions and intersections are all random to affect a kind of live experience for the viewer.

LN Does this “live” experience also involve sound?

SS Yes. For the Rome installation, live-recorded sound experiments accompany the video installation, such as a squeaky motor that ended up in the mix. There’s also machine feedback; I came in one day and the sound system was making a “kerplunk” sound that became part of the soundtrack. The machines, just like the paint, are evolving materials.

LN It sounds Cageian.

SS Absolutely. When you’re in it, you can’t tell what’s ambient and what’s recorded.

LN How do the specific spatial qualities of the Rome gallery affect your approach to the exhibition?

SS Obviously the video installation is talking to the curved walls of the elliptical gallery, which is very special, given that the walls of most galleries are flat and perpendicular. I’m also drawing attention to the smooth stone floor, using it as a surface on which to materialize light using paint. For me, the spill of light has always been a painterly gesture.

LN Particularly in Rome, where light is such a powerful motif in Baroque painting and sculpture.

SS Yes, and also Baroque architecture, with its extraordinary activation of space through light itself. So I’m thinking about the history of the building and the scale and height of the ceiling, and playing on that with regard to the idea of the planetarium: what’s interior, what’s exterior, and how to harness the architecture to become part of the space of the work itself. Here I can make painterly gestures into filmic gestures, and filmic gesture painterly, and sculptural gestures filmic, and break down the frames between them all.

Sarah Sze, Gagosian, Rome, October 13, 2018–January 26, 2019

Artwork © Sarah Sze