Urs Fischer mines the potential of materials from clay, steel, and paint to bread, dirt, and produce to create works that disorient and bewilder. Through scale distortions, illusion, and the juxtaposition of common objects, his sculptures, paintings, photographs, and large-scale installations explore themes of perception and representation while maintaining a witty irreverence. Photo: RobertBanat.com

Madeline Hollander is a New York–based artist and choreographer who works with performance and video to explore how human movement and body language negotiate their limits within everyday systems of technology, intellectual property law, and pop culture.

Natasha Stagg’s books Surveys and Sleeveless: Fashion, Media, Image, New York 2011–2019 were published by Semiotext(e). Her writing also appears in the books You Had to Be There: Rape Jokes, by Vanessa Place, Intersubjectivity, Volume 2, edited by Lou Cantor and Katherine Rochester, Excellences & Perfections, by Amalia Ulman, and The Present in Drag, edited by DIS, among others. Photo: Roeg Cohen

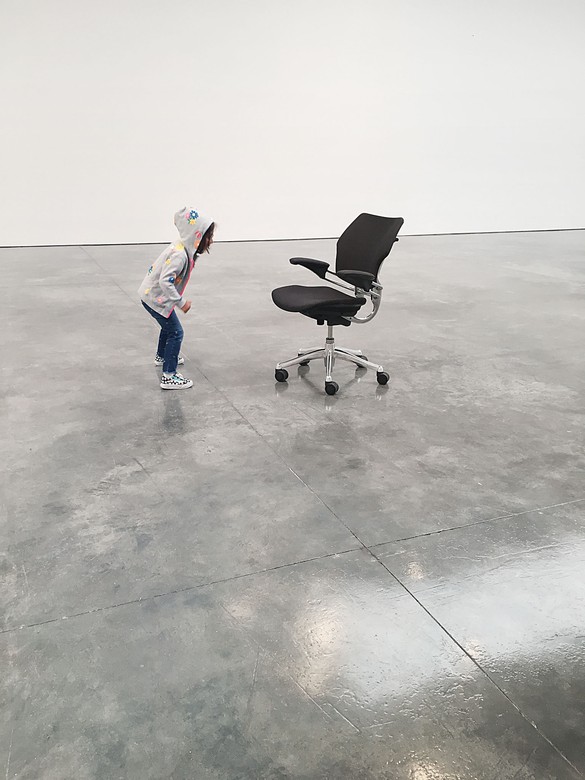

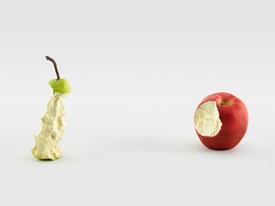

I visited Urs Fischer in his studio last year to talk about the beginning stages of PLAY, an interactive exhibition involving office chairs that have been rebuilt as silent, reactive robots with varying levels of autonomy. Before the chairs were physical objects, they were rendered on a screen, in an animation Fischer showed me to explain his hiring of a choreographer to help him with their movements. He also showed me older sculptures and other projects he was working on, linking them all with his thoughts about art, objects, and an audience’s projected experience. Nearby stood an early version of Things (2018), a slightly larger-than-life-size aluminum statue of a rhinoceros with a photocopier, a laptop, a vacuum cleaner, and many other things partly submerged in its silver flanks, its size and strangeness a distraction from our conversation. Like Untitled (Bear/Lamp) (2005–06), a massive lacquered-bronze teddy bear impaled with a desk lamp, Things in part represents our unwillingness to accept simultaneity. “Let’s say you see that chair,” Fischer explains, “but you have a very different association of what that chair is than I have. Maybe you think of your grandfather and I think of the color red, or whatever. So it’s totally different but you perceive the same object. So, to have an object that is two things at once, it’s almost a dumb version of a more complex thing, the thought that everything goes through you, like sound, other people’s anxieties, nature. If you go to nature, you feel it. Everything basically passes through your existence. As if you’re not a defined thing. You see yourself as a defined thing in your mind but then everything just slides right through it.”

The “protagonist” of Things, as Fischer calls the rhino, is organic and heavy, a creature that “almost pushes through time.” It was important in this case to anchor the idea with an animal: “I mean, if you feel something for anything, it’s probably not the photocopier. All these other things are interfering. They’re nothing, you know, they’re just bullshit.” In PLAY, though, the protagonists are pieces of office equipment while the interference comes from us humans. As Fischer points out, the work’s viewers may bring entirely different associations to these chairs—a grandfather, the color red—and through the use of highly sensitive and sophisticated machinery, he has developed an ongoing depiction of our emotional projections onto them within a defined space.

A year after my first studio visit, I found Fischer, choreographer Madeline Hollander, and a team of engineers testing a few of the robot chairs in the Gagosian space on West 21st Street, New York. The gallery had been rigged with discreet sensors that measured the whereabouts of both the chairs and the humans present, immediately implicating each party in the performance. A green chair spun listlessly in a corner while a shorter red one crawled curiously toward us. A blue one’s back had been disassembled, its exposed circuitry resembling a raw nervous system next to its lifelike colleagues. Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, Fischer and Hollander discussed the many ways it could go, depending on the participants’ perceptions. As we talked, engineers working on laptops sat on metal folding chairs around a table, while gallery staff sat on their own rolling office chairs at their desks. The robot chairs, on the other hand, took up the entire room, nervously zooming around it or pacing the walls, as if perusing art that wasn’t there.

Urs Fischer There are so many different elements to a project like this. Did you get a chance to see inside the chairs?

Natasha Stagg Yeah, I saw the masses of circuitry, wires, blinking lights.

UF There’s no way one person could construct a project of this nature—there are nine different sensors involved, for instance, which collect information that’s continually updated and inputted into the chairs. It’s beyond complex and I’m not a technical person per se.

NS Right, so many moving parts and interrelations.

UF So many, but in the end, despite the complexity of the parts, the exhibition as a whole is pretty simple. It’s about what you, the viewer, project onto it. It’s not about chairs, it’s about humans.

NS How so?

UF It’s the human who projects onto the object. The object is nothing and everything, you know? The chair is just a chair; it could be something else. PLAY isn’t about technology—that becomes irrelevant when you look at it.

NS So the different styles and colors of the office chairs you’re using, those tie into our projection?

UF Yes, we read different emotions into different colors. It’s also an aesthetic choice: if you line the chairs up, you build a spectrum. Color gives us options, another variable. You read something else into the red chair than you do into the green chair doing the same moves. You just do.

NS Yeah, I was noticing the red chair seemed more aggressive, but then I was wondering if I was just making assumptions or interpretations based off my own references rather than its actual behavior.

UF Right. The red one always reminds me of a Valentino dress. There’s a behavior script that could as easily be activated in any of them at any given time. All the chairs take on different personalities during the day, they change the pattern of their behavior, nothing is set. If the green chair were on the same script and behaving the same way, would it still seem aggressive to you? This goes back to how we project onto things. You won’t experience the same thing twice. Everything is variable and changing. In their gentle ways, I hope they can evoke a broad range of emotions and reactions. From shyness to flirtation, from passivity to aggression. Basically, when I say that the work is about people, I mean it’s about expectations. There are some choreographed elements where the chairs show very articulate movements and coordination, recognizable patterns and formations. But the majority of what they do is behavior based. They will take their clues from the activity in the space. This leads you to the place where you relate to the work the way you relate to another human being, or an animal, or really anything that’s alive and moves. As we try to read what’s going on around us we constantly project onto anything. Humans are little projectors.

NS When you say there’s a choreographed performance, is it obvious that the chairs are assembling in a formation?

UF At times, yes. Some are clearly in formation and some are exploring other types of choreography. Madeline did an amazing job with all of them. It was highly educational. There’ll be a lot of these layers. We have to figure out what will work in the space and with varying numbers of people.

Installation video

NS And isn’t it also the case that the ways in which we project onto the chairs, and our responses to them, will affect them over time?

UF Yes, the chairs’ reactions are dependent on the audience, and as they interact with audiences more and more, and as we log their interactions with people, we try to get to the point where they can evolve behaviorally. That’s a long way from now. In the beginning stages they’ll read body language in a very basic way, like whether you’re static or active. What I’m looking for is an experience that’s different for everybody every time. Something that never repeats itself. So in a way, the exhibition puts people on display as much as it does the work in the space. They become one.

NS Can you tell me about the show’s title, PLAY?

UF I’m curious to see how people play, how they interact, how they try to figure things out. We can’t help it, our urge to structure everything. Order. You have play in pretty much anything. Politics are play to some degree—not child’s play but animals’ play. Play is a way of interacting with the world, testing it. Real but not. A simulation.

NS The more recognizable, programmed choreography—could it continue if someone interrupted it? Or would the programming be overridden by the new stimulus the chair has received through the sensor?

UF Yeah, the audience can interrupt it. The programming allows the chairs to check for themselves if they want to resume what they did before the interruption or move on.

The life of the project comes down to individuals. It’s dependent on what they bring to it.

Urs Fischer

NS There are so many decisions. That’s great.

UF If you like to make decisions, that’s great! The life of the project comes down to individuals. It’s dependent on what they bring to it. There are so many little decisions that somehow narrow down what it is, but also open it up. I’m not interested in controlling all the elements that get implemented; what I focus on is the few core things I need, and then the rest should be much more varied than what I can bring to the table. All the amazing people that help me leave a mark on the work. It’s a conglomerate of thought, imagination, and, to a large degree, limitation. A collective effort, with lots of little nooks.

NS I’m picturing a room filled with people. The chairs, in their sympathetic way, are trying to create a dance for them. What if there are too many people? How do you get people to let the performance happen?

UF At this stage we don’t know, we’ve never had a room with a hundred people in it, or even all nine chairs working simultaneously. There will be tests, experimenting, and insight gained from that. There’s probably a cutoff for the number of people who can cohabit the space with the chairs. The chairs, when outnumbered, disappear. That said, this is interesting because then there’s a new situation for the programming to account for. I often think of Grand Central Station at rush hour, the agency of everyone’s movements. And then the ones who wait or just wander amongst the crowds on their way to some place, home or work. It’s all transit.

NS If we think of the exhibition as a metaphor for our relationship to artificial intelligence and how it’s affecting the world, I’m sure that everyone will just let it happen, let themselves be instructed, because that’s the way things are moving, you know? People defer to machines in so many cases.

UF Oh, AI has always existed, you know, in some form in nature. I try to keep PLAY from being only about technology. The idea is to make the chairs so graceful that we don’t even think about that element. Everything we do is part of nature. Certain topics just overwhelm us with fear. Our imagination goes wild.

NS So that the work becomes more generally about our perceptions of objects.

UF Yeah. That’s why the object itself isn’t very interesting. You see, these were chairs I had in my office. Even though they’re now 90 percent remade, they’re still just that: office chairs.

NS I find myself feeling something for the object even though it has no face or limbs, just its movement.

UF Glad you do! I dream about them by now. I think all of us here do. We’ve built relationships, surprising experiences of coexistence. You know, we people, we’re assholes, basically—we look down on everything nonhuman. We see a dog and we put ourselves above it. I’d like to get to the place with this work where viewers may still see themselves superior to the chairs, but they’ll respect that the chairs have their own thing going. I want to build a respect between the viewer and the object—not just “Oh yeah, I get it, I can crack the pattern,” or “I can make it do what I want,” or “I’ll figure this one out.” If the chair decides that it’s had enough, “I’m not taking this shit” and splits, you tend to take that personally. Maybe you reconsider your assumptions of superiority. It’s a push-pull, our programming, or patterns of behavior. That’s basically the project at the core of it, for me. To give and to take. Let’s see.

NS There does seem to be a common fear of technology and machine learning, though—that it will outsmart you eventually.

UF Yeah, good. I mean, we’re not that smart to begin with.

NS But we’re creating the machine, so we don’t want to be outsmarted by it.

UF Our species creates all sorts of things, but look at what else we do: we tap into natural resources like there’s no tomorrow, knowing it’s bad for us as a species and for the rest of life on this planet. But we do it with very elaborate, smart machines. . . . There are a lot of things we do that we don’t want to talk about because we don’t like the solutions. We procreate like crazy, creating more of us, caring about the ones close to us but not about a bigger picture. We just mess everything up. How smart are we? I tend to think that we’re idiots. We’re smart enough to do things but too dumb to understand what we do. The fear of machines outsmarting us, the feeling, the emotional side of this—I don’t think that’s new. The world has always been ending. The apocalypse is as old as history, just with different ingredients.

NS And the chairs aren’t trying to learn about human weakness. They’re not learning about us for someone’s gain.

UF No. If you think of them as a very simple species, they will try to learn more about us, but just to communicate better.

NS Or not for the same reason Amazon’s Alexa, say, would try to learn more about us—to gather data for somebody else to make money.

UF Humans are always collecting data for a specific, usually selfish reason. The chairs can’t be selfish in the same way: they accumulate data in a closed system. What they look for isn’t individualized in any way, it’s just to enhance their own continued movement and behavioral flexibility. Basically to better serve.

NS Do you see the chairs as an extension of your earlier works?

UF Yeah. Totally.

NS Any in particular?

UF Many, but most immediately I think of Nach Jugendstiel kam Roccoko [After Jugendstil came rococo, 2006], the cigarette pack that moves through space and then starts to fly. That was driven by a primitive mechanism in comparison, but as with PLAY, there were stories you could read into it. Stories, fictions, have no physical body. All these works do is move. Movement resolves rigid form, like a Calder mobile. In this way the cigarette pack is not dissimilar from PLAY, with the main difference being that PLAY is actually making contact with you. It relates.

NS Right. And unlike the ordinariness of the office chair, a cigarette pack is loaded with meanings. A person can read cigarettes as a taboo, something tempting, something archaic.

UF If they want, yeah. But the cigarette pack really could be anything. Why I liked it is that it has a disposable nature. An empty shell, thrown away after it’s served its purpose. At which point it becomes liberated.

NS So how do you assume people might read the chairs, if they do? Even though they’re more neutral, they’re something designed.

UF I could tell you how I read them. That’s about all I know.

NS How do you read them?

UF I love chairs. They’re made for the human body. They’re the one object besides clothes that most resembles the body because they’re specifically made for that purpose. We stand, we lie, but then we sit. There’s so much variety in chair design—a very colorful manifestation. Beds might qualify too.

NS The chair has to be one of the most often-designed objects of all time.

UF It is. That’s why I picked these in particular, because they’re ergonomic chairs. They weren’t designed from just an aesthetic point of view. And being ergonomic, they tie into the economic: your company doesn’t want you to have back problems, it wants you to be minimally impeded, so you perform better. These chairs are comfortable but they’re mainly a workplace chair. They need to function and to fulfill the demands of the workplace, which relate to economics and efficiency. The emotional and aesthetic aspects of the design just make you feel better about that.

NS You can define an office by its chairs. I once worked in an office where we weren’t allowed to sit in anything but Eames chairs, which actually weren’t that comfortable. Beautiful but not comfortable.

UF They’re designed for their look, not for ergonomics, and you can tell at the end of the day.

NS Madeline, could you tell me about the choreography we’re looking at right now?

Madeline Hollander We’re in the simple random walk phase. They’re about to start a wakeup sequence—that’s what we’re working on, testing the wakeup sequence, which occurs after they’ve been charging overnight. Every morning they come to life, and before the gallery even opens, one chair, the ringleader, will go around to each of the sleeping chairs and do this little nudging behavior and wake each one individually. But even this will be different every day based on where they’re at from the day before.

NS The ringleader chair will be different, too?

MH Yes. There are many different personalities, and we can shift personalities and behaviors per chair and per day and within set time limits. More than that, it depends on the audience. If someone begins stepping in and following a chair, it may decide to shift into a shyer behavior instead of an aggressive behavior, a behavior where it’s more interested in corners of the walls than it is in people.

UF Or maybe the others come to help.

MH Exactly. Or if there’s a group of people, there might be two very social chairs who will be interested in that crowd and kind of help the less social chairs.

UF The whole objective is to make the chair relatable. It doesn’t need to be human, but it needs to be something we can relate to as human beings.

MH It should be able to conjure empathy.

UF And then once that’s established, it will engage in next-level behaviors, whether as an individual or in a group.

MH We have what I call personality scripts, of which there are ten that rotate among the chairs. Depending on their tendencies, their parameters, those scripts determine which chairs will end up pairing with each other, or joining together in groups. And their interactions aren’t necessarily always relatably human—it could be as if a gust of wind had just entered the gallery and they’ve all gotten blown in one direction.

UF Yes, sometimes it’s poetic. Sometimes it’s architectural and related to the space. We want surprises and we want layers.

NS How did you two find each other for this project?

MH Through Angela Kunicky, at Urs’s studio, and the neuroscientist Leah Kelly, whom I’ve worked with before. I’ve mostly choreographed dancers but I’ve also worked with objects. Most of my research is in gestural interaction.

NS How is this project a departure for you, if it is? Is this the first time you’ve worked with robotic mechanisms?

MH This is unlike anything I’ve ever done. But I’ve worked with robotics before, and I’ve done a lot of motion capture and a lot of choreography with gestural interfaces and interfaces for new tech. So this project was a perfect hybrid of all these other pieces coming together in an intimate, animate object.

NS When you say “personality scripts,” is that a term you came up with just for this project? Or do you use that term more generally in choreography?

MH A whole new language emerged from this process. Behavior scripts, personality scripts, movement sequences, group choreographies, micro-movements, beats—it’s a fusion of my choreographic terminology with the software and the parts of the chair. We have a whole vocabulary specific to this process of melding three distinct discourses to communicate seamlessly. Or more than three, actually: the programmers, the animators, the engineers, the choreography, and the hardware all have their own discourse. What was so fascinating for me, as a choreographer, was how much variation you can get from just the word “footing,” say, which is the wheels spinning, acceleration, speed variation, and seat angle. It’s kind of like having nothing above your hips: there are no arms or head to work with, so how much can you get across meaning-wise in twisting the feet angle with the hip angle and then including acceleration, rate, and whether you’re going forward, backward, or at an angle? Combinations of all of those really do evoke different personalities. So you can have a chair that looks like it’s limping or one that looks like it’s superexcited or flirting or energetic or about to collapse, based on different combinations of those very few variables.

UF It was important to reduce the movable elements.

MH Right. More limitations.

UF There’s beauty in restraint—in life generally, but here the restraint results in more grace. Imagine if the armrest were going up and down and waving—the chairs would be like clowns. It would become entertainment.

MH And even with these limitations, there are endless sequences and endless behaviors available. The personality scripts are like the baseline—kind of how each chair gets dressed in the morning. Then we can assign how often the personalities switch. But there are even more variables: we’re making day scripts, where at certain hours some of the personalities will be way more social or way more introverted. There are ones that incorporate a lot more choreographic sequences, or movements pulling from sports and culture and dance, and then others that pull from conversation and interactive sequences.

UF As data of the movements through space accumulates, we’ll try to understand patterns, and which elements are successful one way or another. From there we’ll take it to the next stage. When the exhibition opens, it will be like the chairs are leaving home for the first time and will have to learn a lot. The idea is that they become gradually more and more their own, continuously learning. This is just the beginning.

MH And the only way to learn will be having the show’s run and interacting with a public that’s not familiar with them. Because right now I know all of the limitations, so our testing isn’t really giving us the data required for the AI to get smarter. There are so many factors, you know: What does a crowd do, what does a group of kids do, or a dog, or people who leave their bags on the ground? There are so many different sensors and ways that the chairs experience and react to space that we haven’t really gotten to explore. They’re not going to need us anymore after a while.

UF I’d say they’re eleven-year-olds now.

MH Eleven? Yeah. Smart eleven-year-olds.

UF Eleven-year-olds who think they’re fourteen-year-olds. We’ll try to get them to eighteen by the time the show opens, no?

MH Sixteen, seventeen . . .

UF We’ll try.

NS They can get their drivers’ licenses.

MH That’s the goal, yeah. Because then they can drive us around. And that’s kind of what we’re working on right now: figuring out ways to herd or corral not just the chairs but the viewers. The chairs will have to learn how to approach situations for the best results. For instance, if three of them travel in a line, that will probably make people more likely to move back. So if we want to present a bigger choreography, where it’s more of a spectacle or a dance, there’ll be ways to have the chairs announce that they want to clear the stage, in a way that’s not aggressive but inviting. I think a lot of the movement in the installation allows you to fluctuate between anthropomorphizing and deanthropomorphizing the chairs. They’ll kind of switch roles, so you’re flipping back and forth between those spaces. And what’s interesting is that the viewers also go between being the audience and being a part of the installation. That might be confusing for people who may be anticipating something more like a performance, but the chairs are participating, watching the viewers and literally making sense of their behaviors, working around or reacting to them. It’s a real communication system.

UF I look forward to watching people trying to make sense of it all. It’s like when you go to a concert and you don’t focus on the people onstage. Instead, you start to look at all the people looking, and it’s awesome.

Urs Fischer: PLAY with choreography by Madeline Hollander, Gagosian, West 21st Street, New York, September 6–October 13, 2018

Artwork © Urs Fischer