Gregory Zinman is an assistant professor in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His writing on film and media has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and October, among other publications. He is the editor, with John Hanhardt and Edith Decker-Phillips, of We Are in Open Circuits: Writings by Nam June Paik.

Every scholar granted access to an artist’s archive dreams of that moment of serendipity: stumbling across a passage that confirms a long-held speculation, gives voice to an artist’s intention, or unlocks a connection to an unstated influence. Even more alluring is the idea of discovering an artwork long obscured or lost altogether. This latter occurrence is rare, the academic equivalent of real-life art-historical jackpots like Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Martin Kober’s—a painting behind his couch in Buffalo may be a Michelangelo—or the six possible Willem de Koonings found by the Chelsea art dealer David Killen in a New Jersey storage locker. Yet the archive nevertheless promises the dream of discovery: opening up a new passage of art history, providing a corrective to the record and the accepted wisdom, counteracting master narratives, and expanding the possibility of finding meaning in the creation of art.

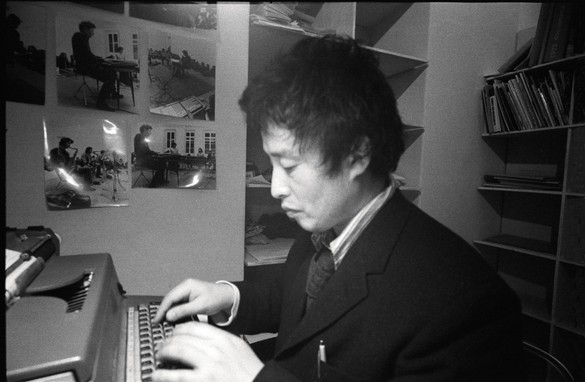

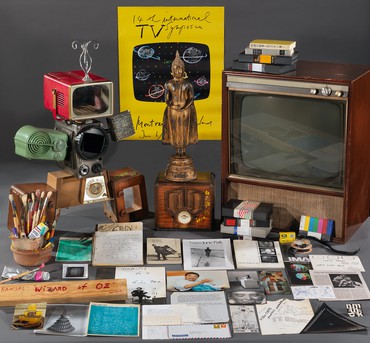

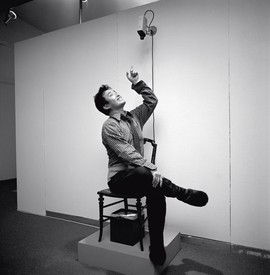

The reality of the archive is different, however, as I learned during the nine months I spent immersed in the archive of Nam June Paik, the Korean-born visionary whose innovations in using television and video as artistic mediums transformed the cultural landscape of the twentieth century. Paik’s archive was acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in 2009, three years after the artist’s death, at the age of seventy-three. Its materials, culled from his three Manhattan studios, required two tractor-trailers and five box trucks to move to Washington, DC. Once at SAAM, the materials were divided into two parts: objects and paper. The first of these sections resides in SAAM's off-site facility in Largo, Maryland, and contains paintings, works on paper, photographs, videotapes, and sculptures by Paik, as well as images of David Bowie, Allen Ginsberg, Humphrey Bogart, and others, all festooned with his colorful writing and doodles. The object archive also houses a hearty sampling of his inspirational and working materials, including Canal Street schlock bought in bulk, such as toy airplanes and plastic robots, alongside scores of vintage cameras, radios, and antique television sets and cabinets. While this collection is fascinating on its own, my remit involved the other section: the paper archive, measuring 55 linear feet—a veritable blue whale of paper.

This paper archive consists of box after box, file after file, page after page, of documents such as phone bills, missives haggling over costs of equipment and shipping, and tax information. It contains correspondence in which Paik was chasing down money and proposals for projects that never received funding and so were never realized—his suggestion that he become a “peace correspondent” for public television, for example. But this papery flotsam points to a life, one not of spotless galleries and tony auction houses but rather one of almost comical mess, lived in piles of electrical cords, hollowed-out CRTs, and seemingly endless handwritten lists of people Paik wanted to call or had promised to call back.

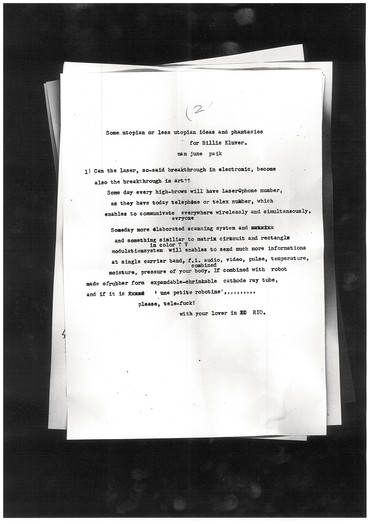

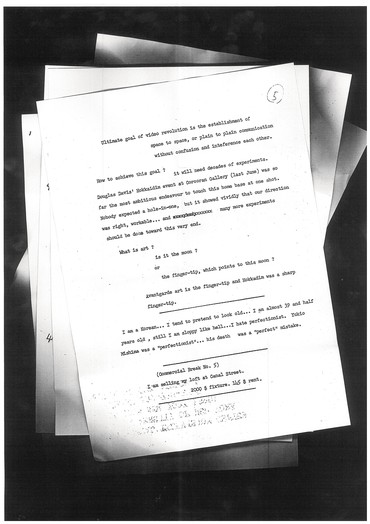

This overwhelming tide of material also contains substantial project plans and long essays, many of them unpublished or in drafts that differ from their published versions. Wide-ranging, discursive, and often astonishing in their originality and prescience, these writings cover a variety of topics, from the oil crisis of the 1970s to the migrations of ancient populations in Europe and Asia. Others forecast facial-recognition software—this as early as 1966—and, more famously, the “electronic superhighways” of the Internet, as early as 1974. Some pieces are concrete in their specificity and limpid in their aims, as when Paik wrote, in “Binghamton Letter” (1972), that the “ultimate goal of video revolution is the establishment of space to space, or plain to plain communication without confusion and interference each other.” But he also had a more exploratory mode of address. A sixteen-page “fantasia” nominally addressed to Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver, for example, includes the passage, “Maybe we can send certain waves directly to brain, which modulates brainwaves, and entertain, enlighten, expand the brain,,[sic] a kind of electronic LSD.” Paik repeatedly stated that the challenge of using new media was to “humanize” the technology. While this goal could have lofty, even utopian ramifications, he also refused to ignore the baser, even carnal intersections of technology and humanity that would become powerful cultural forces, writing in the mid-1960s about sex robots with “expandable-shrinkable cathode ray tube,” concluding, “please, tele-fuck! with your lover in RIO.”

Something that becomes clear in reading through an artist’s archive is that the artist in question was a person. Not only a significant historical figure—though that, too, surely—but someone with friends and collaborators, someone with debts to pay, someone who tried to challenge himself as an artist. Yet the archive doesn’t serve as a biography, or as a rounded accounting of a life. Too many details are missing.

Partly through his background in the Fluxus movement, partly through his ingratiating personality and a sense of humor that ranged from witty to juvenile, and partly through the Western racism that made some unwilling to look past his aphoristic broken English, Paik was often described as “funny,” a “prankster.” “Chaotic” was a familiar descriptor of his working methods among both critics and collaborators. And yes, Paik embraced both chance and indeterminacy as central components of his practice, but reading his writings makes clear how he made plans and worked through ideas: methodically, deliberately, but also with flexibility when something needed to change, or when he came up with a better option. He also absorbed and repurposed lessons from philosophy, political science, music, and painting and applied them to his art. Reading Paik adds unexpected depth to his work, and gives us access to his inspirations, frustrations, methods, and process.

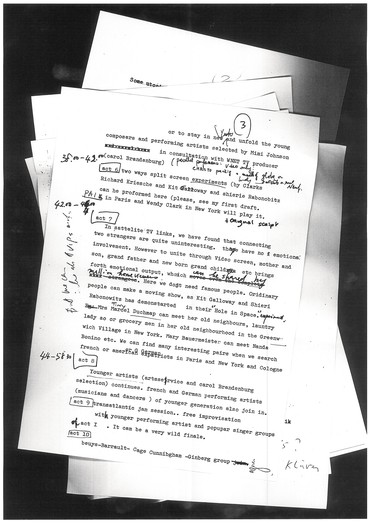

In his art making, Paik habitually oversaw dozens of projects at the same time. He wrote the same way, iteratively, crossing out items and revising, reordering, rethinking, continuously plan-B-ing. His love of idiom and adage comes to light in the archive through notebooks and scrapbooks containing cut-and-pasted passages from Diderot, Heidegger, Nietzsche, and Lao Tzu. (Cutting-and-pasting, of course, was the same technique he borrowed from Dadaist photocollage and applied to his video editing.) Paik blended his lifelong interest in philosophy and modernist music with an insatiable curiosity about the new. He was convinced of the salubrious potential of an accessible avant-garde, imagining poetry by Ginsberg and Jackson Mac Low, music by La Monte Young and John Cage, and films by Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas being piped into every home by a “laser TV station.” Equally at home in Darmstadt and Danceteria, he made works that could be seen on public television and collected by museums. In letters and plans, he courted pop stars like Bowie, Laurie Anderson, and the Thompson Twins, then gave them the same platform in his art that he granted to Merce Cunningham, Joseph Beuys, and Charlotte Moorman. In We Are in Open Circuits, many of these letters and other works find new life as concrete steps in the creative process, offering a window into the mind of one of the most important artists of the postwar period.

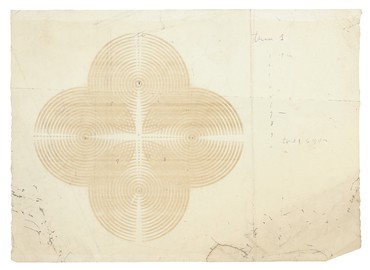

Arguably the most significant piece of “writing” I came across in the Paik archive, though, didn’t make it into We Are in Open Circuits. Early on in my time at SAAM, I read through folders containing files related to Paik’s time at Bell Labs, in Murray Hill, New Jersey, where he was an artist in residence at the telecommunications research and development center in 1967–68. The folders contained stacks of continuous-feed computer printout paper, which in turn included a series of numbered studies for various works, among them what would become Confused Rain (1967). My eye landed on another page, titled Etude 1, also dated 1967, and credited to “Paik/Noll”—the latter a reference to A. Michael Noll, a Bell Labs engineer who, with his colleague Béla Julesz, exhibited the first show of computer-generated art in the United States, at the Howard Wise Gallery, New York, in 1965. (While Noll helped bring Paik to Bell Labs, he told me that he does not recall working on Etude 1 with the artist). Another sheet in the folder showed an image of four overlapping concentric circles made up not of lines but of letters forming the words DOG, GOD, LOVE, and HATE. Looking at the code—yet another language learned by Paik, who also spoke or wrote Korean, English, German, French, Chinese, and Japanese—for the printout of Etude 1, it quickly became clear that the image had been output by a version of the program. The studies, as well as Etude 1, were composed in FORTRAN 66, a computer language long out of date. The scholar’s archival fantasy had become real: this was a previously unidentified work of Paik’s, and it turned out to be one of the earliest pieces of computer art ever made by an artist. What Paik created at Bell Labs was necessarily minimal, the work of a neophyte programmer using notoriously buggy and complex General Electric mainframes. Even so, the outcome remains appealing in its simplicity and sly conceptual and material reversals—code into words, language into geometry, music into image.

Of course, nothing can be “discovered” in an archive without the work of countless others. Ken Hakuta, executor of the Paik estate, wanted a home for the artist’s materials. Elizabeth Broun, director of SAAM at the time, agreed to take and archive them. John Hanhardt, then SAAM’s senior curator of media arts, working with the museum’s registrar, Lynn Putney, waded through them, making countless decisions about what should and should not be preserved. Christine Hennessey, the chief of research at SAAM, and Hannah Pacious, the archive’s coordinator, and others all worked tirelessly to inventory, catalogue, and make the materials accessible to researchers. In other words, Etude 1 was already there in the archive. What scholars do is attempt to make meaning from what they “find.” In this case, it became my challenge to think through how Paik understood, made use of, abandoned, then prophesied the use of computational media to make a new kind of art.

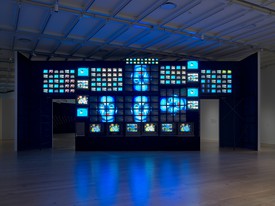

As was the case with Etude 1, the most generative thing about reading papers in an archive is how they provoke more questions. Sometimes, to answer those questions, you have to cross-reference other archives. When John suggested that we edit a selection of Paik’s writings into a collection, we naturally availed ourselves of the resources at SAAM, but I also traveled to the Paik estate in California, where I found his Bell Labs notebook in the bottom of a box; to the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York; and to the John Cage and Charlotte Moorman archives at Northwestern University, among other repositories. John’s and my coeditor Edith Decker-Phillips reached out to the Joseph Beuys Archive in Düsseldorf and returned to the Sohm Archive, in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, to pore over the documents that had formed her previous compendia of Paik’s writings, published in German and French, in order to obtain materials for our volume. Building out context for the writings in the book meant soliciting the memories and recollections of people who knew the artist. And so we conducted interviews with people like Carol Brandenburg, a longtime Paik supporter and producer at WNET, who helped orchestrate and navigate the complex constellation of people, stations, and technologies that constituted Paik’s three satellite works of the 1980s, Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984), Bye Bye Kipling (1986), and Wrap Around the World (1988), which combined resources and talent from dozens of countries. We called on the resources of Peter Wenzel, owner of one of the world’s most significant collections of Paik’s published writings and exhibition texts. We talked to contemporaries of Paik’s such as the video artist Steve Beck. We studied previously published interviews for corroborations and elaborations, and relied on a previously unpublished conversation between Paik and fellow Fluxus artist Dick Higgins that had been incorporated into SAAM’s archive.

I never met Nam June but John had curated his work, written about him extensively, and considered him a good friend. Before a screening of Zen for Film (1962–64), Paik’s zero-degree investigation of cinematic materiality in which a reel of clear leader accrues dust motes and scratches as its imagery, he told John to kick the reel across the floor before the screening, in order to gather further scuzz and make the image more complex. That’s information that’s not in a letter, not in a book, not in an archive. These are what Paik scholar and curator Hanna Hölling calls “microarchives”—repositories of knowledge that escape inscription. Such microarchives include the institutional memories of museum registrars, a conservator’s knowledge of CRT screens, and the anecdotal remembrances of someone like Jon Huffman, Paik’s longtime assistant, project manager, and now curator of the Paik estate. All of these different people, resources, and institutions are crucial components in the construction of an art history.

We Are in Open Circuits includes an essay called “Random Access Information” that Paik wrote for Artforum in 1980. It is at once provocatively speculative, digressive, and whimsical—a perfect encapsulation of Paik’s rhetorical style. “We have a thing called art and we have a thing called communication,” he wrote, “and sometimes their curves overlap. (A lot of art does not have much to do with communication and a lot of communication has no artistic content.)” To read Paik’s writings is to try to identify and illuminate such moments of intersection. The result, of course, is not definitive, it’s a collection. An assemblage. An attempt to mount a few new antennae on the tower of Paik’s oeuvre as signals to others. It provides some insights into Paik as an artist and innovator, and it is designed to spur others to further finds and interpretations and, ultimately, to new art histories.

Artwork © Nam June Paik Estate