Alison M. Gingeras is a curator and writer based in New York and Warsaw. Her curatorial history spans from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; and Palazzo Grassi, Venice, to the storefront curatorial space Oko in Manhattan’s East Village. She is currently an adjunct curator at Dallas Contemporary. Independent publisher Heinzfeller Nileisist published Totally My Ass and Other Essays, a collection of Gingeras’s writings, in 2019. Photo: Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Gingerass), 2003 (detail)

The Best a Man Can Be?

Middle-aged men glare at themselves in middle-class medicine cabinets. A fragmented, cacophonous assault of talk radio provides the soundtrack for their introspection: “Bullying . . . the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment . . . masculinity.”1 The familiarly velvety voice of the ad’s narrator interrupts the sonic wall of the news cycle, asking “Is this the best a man can get?” as a clip of the Gillette tagline from a 1980s commercial flashes on-screen. This gendered promise is incarnated by stock characters, an all-American white guy being kissed on his freshly shaved cheek by his generically pretty white girlfriend. Then our culture war bursts through the screen, personified by a herd of marauding tween boys who dramatize the social Darwinism that undergirds capitalist society: the weak are justifiably terrorized by the strong. Cut to a close-up of a blue text bubble: social media rears its ugly head in the narrative with the epithet “freak!!!” The scene dissolves to show a mother comforting her bullied boy while more text bubbles ping with menace: “You’re such a loser.” “Sissy!” “Everyone hates you.” The montage of footage continues at a rapid pace, evoking systemic sexual harassment and teens passively consuming the girls who sell stuff on TV by dancing in skimpy bikinis. The narrator reprimands, “We can’t just laugh it off.” The mantra “Boys will be boys” is chanted by a seemingly endless row of paunchy dads, each standing behind a smoking backyard grill. The camera pans down this Busby Berkeley chorus line of suburban toxic masculinity.

“But something finally changed . . . ,” the narrator intones, as cable-news clips decry headlines about “sexual assault and sexual harassment.” Without calling out the most egregious offenders, such as Donald Trump and Harvey Weinstein, the ad takes on a transformative, even redemptive tenor: “And there will be no going back,” the narrator promises. The collective article we dominates the rest of the spot: “Because we, we believe in the best of men . . . to say the right thing, to act the right way.” Evangelical in the delivering of these correctives, the edit continues with vignettes of bros checking other bros’ behavior—breaking up street fights, cutting short catcallers, serving up positive reinforcement for their daughters, saving the kid from getting bullied. Gillette’s de facto manifesto for today’s manhood ends with the woke corporate slogan: “Because the boys watching today will be the men of tomorrow.”

This capitalist court métrage ends with a new pitch line: “The best men can be.” Rather than just finesse a sales jingle, Gillette has felt compelled to dramatize the current crisis of traditional manhood. In this landscape of gender war, it’s impossible for them merely to peddle men’s hygiene products; first they must sell men on the new confines of their identities. In under two minutes, this rebranding hinges on a deceptively simple grammatical move: swapping the verb get for the verb be. In simpler times, men were just men; all they had to do was obtain the accoutrements needed to enforce their manhood. Nowadays men are the object of scrutiny: they must be deprogrammed, reeducated, and remade to “be” a better version of their gender.

This fragment of pop culture encapsulates a much larger zeitgeist. Masculinity is under the microscope. Fueled by shocking revelations of high-profile men abusing their power, a phenomenon epitomized by the election of the notoriously misogynous Trump in 2016, a populist groundswell has finally emerged that seems to have absorbed certain feminist ideas. Simultaneously, the very bedrock of traditional gender constructs has come to be questioned in even the most mainstream quarters of American public life. While many pundits have heralded this moment as a triumph for feminism, our current societal paradigm shift has had less to do with the liberation of women than with the restraint of men. Whereas the feminist political exigency of the 1960s and early ’70s was centered on concepts of what a woman could be—politically outspoken, sexually liberated, freed from the traditional burdens of domestic life—our current moment is fueled by a radical questioning of male identity. The bra-burning of those years has given way to similarly inflammatory, career-scorching social media campaigns and the CEO-toppling “Shitty Media Men” online spreadsheet.2 Consciousness-raising groups that provided safe spaces where women could share the intimate details of their oppression have been superseded by the public self-flagellations of men ashamed to have participated in systemic misogyny. Public intellectuals such as George Yancy have penned mea culpas that were unthinkable in even the most liberal circles years before. In his New York Times polemic “#IAmSexist,” he confesses, “There are times when I fear for the ‘loss’ of my own ‘entitlement’ as a male. Toxic masculinity takes many forms. All forms continue to hurt and to violate women.”3 Man-hating was once the exclusive domain of radical feminists; now it’s been co-opted by men themselves.

What Sort of (Wo)Man Reads . . . ?

Reading men’s magazines was once considered a normal rite of passage for boys. In the spirit of Camille Paglia’s argument that “men become masculine only when other men say they are,” the consumption of pornography was one of those acts that externally qualified one’s virility.4 Thanks to the eclipse of print media by Internet porn, the natural audience for men’s magazines has evaporated since the heyday of Hugh Hefner, but back in the day it would have been almost an exercise in obviousness to profile the average consumer of such normative manly material. This did not stop PR executives from trying to: “What sort of man reads Playboy?” was the tagline for an ad campaign that ran from 1958 to 1974. Playboy published the sophisticated ads with this headline as a way to distinguish and elevate its editorial product from the smuttier periodicals that competed for its readership.

In the most zealous corners of our current political zeitgeist, this simple reversal

of the gender/power binary effectively prevents us from learning from the voices of those men who actually offer critiques of their own gender.

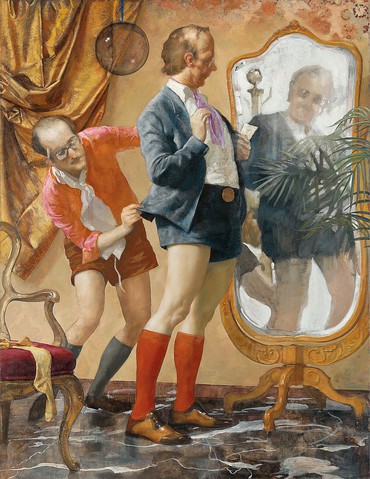

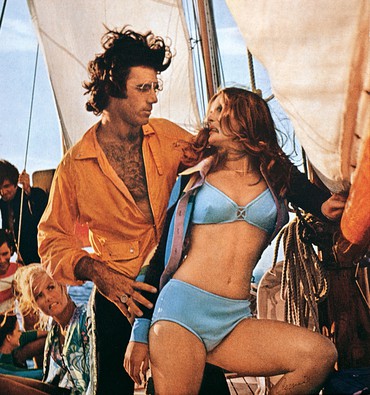

Targeting potential advertisers, these print ads featured a seductive yet unthreatening photographic tableau of a successful, confident American guy in a leisured setting. Urbane straight men between the ages of eighteen and fifty—each model pictured was white, seemingly upper class, and surrounded by attractive women—were depicted at play: lounging on the beach, reading on the deck of a sailboat, buying an expensive suit, riding a horse, mixing a cocktail in a wood-paneled rumpus room, fueling up a shiny convertible. The text below the image would answer the lead question “What sort of man reads Playboy?” with a dazzling description of the typical Playboy subscriber: “A young executive with an event-full calendar. A Playboy reader knows where he’s going and the best way to get there.” This copy would boast facts and figures about the desirable demographic that the magazine regularly reached—vaunting the readers’ high salaries, their metropolitan addresses, the number of credit cards in their wallets—and would urge companies to advertise in Playboy to reach this affluent, aspirational class of men. While the ads just echoed the magazine’s propaganda that Playboy was read “for the articles”—the perfect alibi for its porn-hungry audience—they have now become sociological time capsules in the way they enshrine a golden age of traditional masculinity that has been slowly eroding since the later part of the twentieth century.

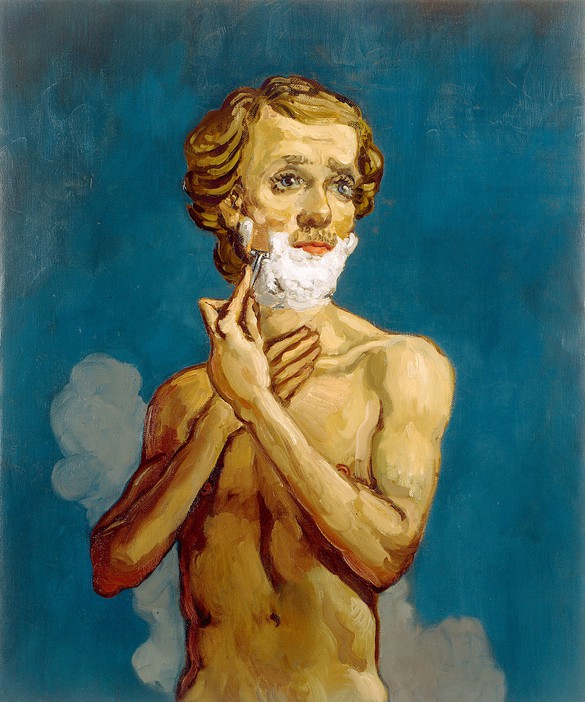

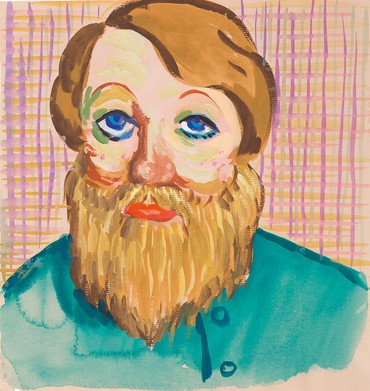

In 1997, John Currin appropriated these iconic Playboy ads as fodder for a series of works titled The Jackass. In an act of Situationist détournement, Currin used gouache to overpaint the expressions on the faces of the nubile young women whose longing gazes are invariably trained on the men who star in these ads. Come-hither looks and coquettish miens have been transformed into horrified scowls, furrowed brows, and expressions of utter disgust. With but a few strokes of the artist’s brush, these trophy women have turned against these men—in essence neutering Playboy’s construction of a certain type of masculinity as highly desirable and readily monetized. With Currin’s minor yet socially scathing modifications, the Jackass works humorously deflate the performance of gender that these men’s magazines were selling to their subscribers while also performing a semiotic reversal. Currin’s overpainted women hold all the power in the battle of the sexes, while these Playboy readers have been transformed into clowns. With the male protagonists positioned as the punch line of the joke, one might be forgiven for mistaking these gouache modifications for the handiwork of a feminist artist. Given that they were made some two decades before our current gender war, it is tempting to read the Jackass series as a curious anticipation of the current public scorn for so-called toxic, even normative forms of masculinity. But if not prompted by the current feminist groundswell, why would Currin turn to mocking his own kind? Instead of anachronistically sweeping up the artist’s work in a revisionist narrative of the battle of the sexes, it is more accurate to reinsert Currin into a long tradition of male authors the very substance of whose art revolves around probing the foibles and excesses of their own masculinity.

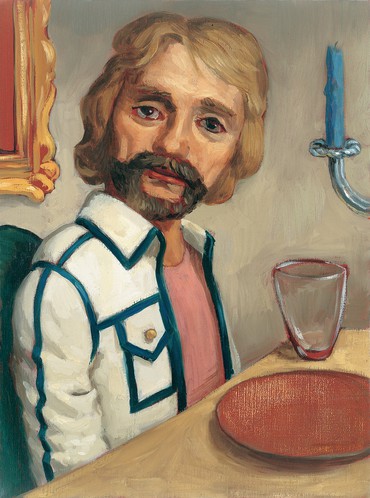

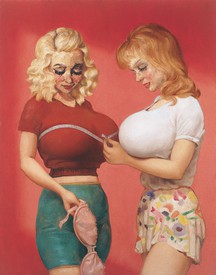

The novels of Philip Roth impose themselves as the literary equivalent of Currin’s work when it comes to representations of masculinity. Both Roth and Currin are artists “who make great comedy of male sexual appetites and failures.”5 While it is impossible to compare literary and visual depiction exactly, both have created works that oscillate between the ravenous sexual desires embedded in the male gaze and the exploration of crippling anxiety produced by masculine vulnerabilities. Both have been criticized for the “thinness of female characters,” while both have also centered much of their narratives on an “obsession with women’s power over men.”6 Satyriasis seems to be an affliction shared by many of their fictional protagonists—whether the strange black-gloved man grabbing at the pneumatic breasts of Currin’s The Wizard (c. 1994) or Roth’s character David Kepesh, who awakes to find himself metamorphosed into a six-foot-tall breast. Roth’s humor and cultural references are bathed in the Jewishness of his native Newark, New Jersey, whereas the cultural texture of Currin’s paintings is rife with the sociological details of an East Coast wasp imaginary. Despite this ethnic divide, both Currin and Roth expertly apply the high language or technique of their craft to subject matter inspired by low culture. “The sick jokes and borscht-circuit vulgarity”7 that pepper Roth’s novels find their echo in Currin’s appropriations that mix “leering, lightheaded kitsch with old-masterish weight as if there were no distinction,” producing what critic Michael Kimmelman named “a dizzying feat that makes every picture seem wholesome and evil at the same time.”8 Roth and Currin are each master portraitists of the male condition.

Yet it is not the best time to advocate for the legacy of Roth and his ilk. With heteropatriarchy under a cloud of suspicion, creators like Roth and Currin who have for decades trained their authorial gaze upon the condition of their own sex have also been caught up in the revisionist backlash. It is a fair question to ask, to borrow the phraseology of the Playboy ads of yore, “What kind of (wo)man reads Philip Roth today?” And further yet, why specifically contemplate the depiction of men in Currin’s work? This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue have been conceived at a time when the primacy of the male author is more fraught than ever. My Life as a Man borrows its title from Roth’s novel as a conceit to prompt reading of the full span of male iconography in Currin’s thirty years of work through the lens of gender politics. After five decades of feminist struggle, to believe that achieving gender parity is tantamount to censuring male voices altogether would be a travesty. Yet in this era of understandable #MeToo rage, many women (as well as members of other groups that have been historically oppressed) feel compelled to radically rewrite the canon so as to silence or downgrade the cultural contributions of men—especially white heterosexual cis-gendered men. In the most zealous corners of our current political zeitgeist, this simple reversal of the gender/power binary effectively prevents us from learning from the voices of those men who actually offer critiques of their own gender.

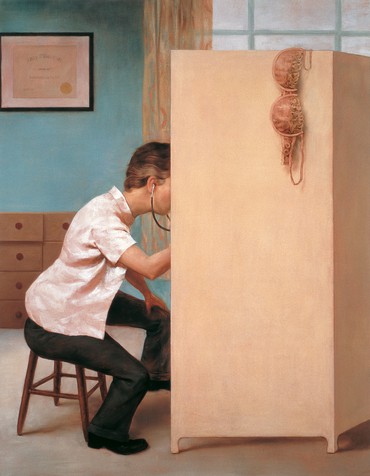

There is immense value for feminist movements—and for humanity as a whole—in carefully examining the portrayals of the masculine psyche that operate in much of Roth’s and Currin’s oeuvres. Their fictional men are more often than not antiheroes. The minutiae of their sexual drives, narcissism, or misogyny are ultimately the subject of brutal lampooning—whether embodied in the portrayal of a lecherous medical professional in Currin’s Dream of the Doctor (1997) or in Roth’s profoundly sexist character Nathan Zuckerman. Both artist and author allow themselves to transgress the confines of political correctness to probe the masculine grotesque; their “mansplaining” takes the form of a ribald autopsy of the flaws, conflicts, and anxieties that dominate contemporary manhood. While our revisionist urges attempt to downshift men’s status from the first to the second sex, any renegotiation of gender politics must involve both halves of humanity. When read as a whole, Currin’s work may be animated by the same existential desire as Peter Tarnapol, the central figure in My Life as a Man: “I wanted to be humanish: manly, a man.”

1Kim Gehrig, “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be,” Gillette commercial, January 13, 2019, video, 1:48. Available online at www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPmuEyP3a0 (accessed June 22, 2019).

2See Moira Donegan, “I Started the Media Men List: My Name is Moira Donegan,” New York, January 10, 2018. Available online at www.thecut.com/2018/01/moira-donegan-i-started-the-media-men-list.html (accessed June 22, 2019).

3George Yancy, “#IAmSexist,” New York Times, October 24, 2018. Available online at www.nytimes.com/2018/10/24/opinion/men-sexism-me-too.html (accessed June 22, 2019).

4Camille Paglia, Sex, Art, and American Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), pp. 50–51.

5Elaine Blair, “Men’s Lib,” The New York Review of Books, February 21, 2019. Available online at www.nybooks.com/articles/2019/02/21/henry-miller-mens-lib/ (accessed June 23, 2019). A review of John Burnside, On Henry Miller: Or, How to Be an Anarchist (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

6David Gooblar, “Roth and Women,” Philip Roth Studies 8, no. 1 (Spring 2012):, p. 9.

7Morris Dickstein, “My Life as a Man,” New York Times, June 2, 1974. Available online at www.nytimes.com/1974/06/02/archives/my-life-as-a-man-by-philip-roth-now-vee-may-perhaps-have-begun.html (accessed June 23, 2019). A review of Philip Roth, My Life as a Man (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1974).

8Michael Kimmelman, “John Currin,” New York Times, November 12, 1999. Available online at www.nytimes.com/1999/11/12/arts/art-in-review-john-currin.html (accessed June 23, 2019). A review of Currin’s exhibition at Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, fall 1999.

Excerpted from Alison M. Gingeras’s essay of the same title in John Currin: Men (New York: Gagosian, 2019), published on the occasion of the exhibition John Currin: My Life as a Man at Dallas Contemporary

Artwork © John Currin; photos: Rob McKeever unless otherwise noted