Negar Azimi is a writer and the senior editor of Bidoun, a publishing and curatorial project. With Klaus Biesenbach, Tiffany Malakooti, and Babak Radboy, she recently curated the first retrospective of the Iranian avant-garde theater director and filmmaker Reza Abdoh at MoMA PS1, New York. She is at work on a book about the 1960s and 1970s.

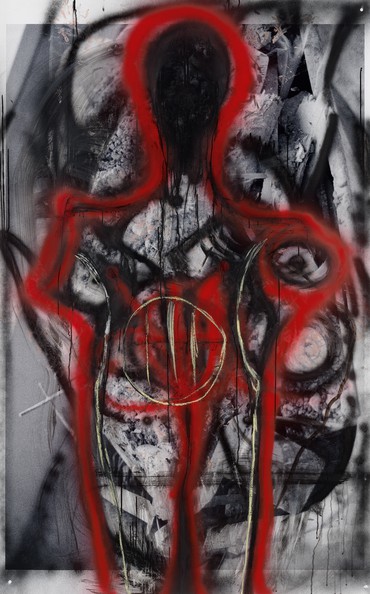

In expressive drawings on photographs as well as figurative sculptures carved from cork and Styrofoam, assembled from refuse and clay, or cast in bronze, Huma Bhabha probes the tensions between time, memory, and displacement. References to science-fiction, archeological ruins, Roman antiquities, and postwar abstraction combine as she transforms the human figure into grimacing totems that are both unsettling and darkly humorous. Photo: Sean Thomas

Negar Azimi Dear Huma, for starters, your rooftop sculptures last year at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, presented under the rubric We Come in Peace, shook me as few sculptures have. They took my breath away with their crookedness and their monstrosity. The word “monster” derives from the Latin root monstrum, which means “divine omen” but also, according to the Old French into which it was adapted, an animal of multiple origins. I use the word with tenderness, the way the monster loved Dr. Frankenstein, or the way Diane Arbus considered her subjects, askew as they were, “aristocrats.” I don’t necessarily want to embed your sculptures in these particular lineages as much as to say I found them incongruously lovely. Can you tell me a bit about what was going on in your head and heart when you concocted these works?

Huma Bhabha It’s the monster I connect with, not Dr. Frankenstein. Dr. Frankenstein is arrogant, he’s not ready to accept his failure, which is why he can’t accept the monster’s otherness. The monster, and other forms of the monstrous and grotesque, inspire me. I had already imagined the prostrate garbage-bag figure as a potential monumental sculpture some time ago and stored the idea away. Then came the commission from the Met, which inspired the companion sculpture. The connection between the two figures was very theatrical; it was as if the roof were a stage or a landing pad on which they had arrived, with the skyline very much a background. Think The Burghers of Calais meets a Marvel comics movie.

NA That’s a remarkable image. I’m equally drawn to your figures because of their striking ambiguity. In the case of the standing figure on the Met roof, they’re intersex, both human and alien, both firmly contemporary in their use of materials and ancient in their evocation of a long history of figurative sculpture, both coming into being and en route to dissolution. It’s all marvelously unclear. The prostrate one, covered in a plastic-bag tarpaulin that to my eyes evokes the fragility of the homeless, is called Benaam, which I understand means “no name” in Urdu. Its hands are cartoonish and it sports a tail concocted from clay and electrical parts. In a way, the work seems to betray your spiritual commitments. Is that fair?

HB Benaam, “without name,” was always for me a monument to the unnamed victims of ongoing conflict. The black covering is literally a plastic bag covering a body that has expired. The hands stretching out from under the plastic signal a last movement, as does the refuse or tail of rubble—a final expulsion. We Come in Peace, which is also the title of the standing five-headed intersex figure, is responding to being summoned by Benaam. They obviously don’t look human in scale or presence, so the scenario between them is open to the imagination. For me, it’s an antiwar statement, but I don’t want to limit the work to one interpretation.

NA “We Come in Peace” is a line plucked from the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, about alien invaders who come bearing an alarming message for inhabitants of Earth. The film is a fascinating relic of the Cold War. I’ve used the stock phrase “alien invader” but I feel like your art is at odds with the standard images one associates with that phrase: it channels empathy and warmth rather than marauding malevolence. Again, you feel closer to the monster than to his creator. What does science fiction offer us, anyway?

HB Science fiction lets me feel less alone in my paranoia. Philip K. Dick’s writings are a big influence on my psyche and my work. One of his most compelling themes is that the Roman Empire never ended. Christianity was absorbed into it and today America is the new Empire.

NA He was not wrong. Dick was an uncommon seer, a Cassandra who lived a tormented life and didn’t live long enough to see the impact his works had. And the truths they held: I guess one of the basic truths of Blade Runner [1982], the filmic version of his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? [1968], is that no matter how “advanced” people may think they are, they revert to their most basic, even malicious instincts. Do you feel that? Do you have a favorite work by Dick?

HB Philip K. Dick was fortunate not to have seen what he predicted. There has been no evolution; we still strive for the same ego-driven bullshit. My interest in P.K.D. is in not only the visionary aspect of his writings but also his writing style, which offers an amazing fusion of unpretentiousness, humor, and imagination that I hope to attain in my own work. I like almost all of his books and short stories, but Martian Time-Slip [1964], The Penultimate Truth [1964], and Valis [1981] are special favorites.

NA You grew up in the 1960s and ’70s in Karachi, often referred to as Pakistan’s largest and most cosmopolitan city. The city’s population swelled after partition, in 1948, as millions of Indian Muslims streamed in. Can you tell me a bit about your experience of the city, but also your family and perhaps, even, your visual universe growing up? What were you looking at as a young person?

HB My work is strongly shaped by where I grew up. Karachi’s population has swelled to 20 million in the last thirty-five or so years. After the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, in 1979, and the Iranian revolution around the same time, Pakistan started to change and the atmosphere became more openly feudal, corrupt, and ganglike. In the 1960s and ’70s Karachi was less built up, there was none of the hideous Third World pop-up architecture that is prevalent now. There was desert on either side of the roads . . . beautiful sandy stretches with the most resilient bushes and mangroves that only grow in the most arid, salty conditions. My mother was born in northern India and my father was born in South Africa. I was exposed to art by my mother, who was a very talented amateur artist. My father grew up during apartheid and left South Africa when he was twenty-four. He traveled around quite a bit, I can tell from old photos, and settled in Karachi in the mid-’50s. Karachi has a rawness that has seeped into my work—the landscape, the crumbling construction, the histories of the region. One fond memory is a class field trip at age fifteen to Mohenjo Daro, the ancient city of the Indus Valley Civilization, and later seeing the art of Gandhara, which shed light on the hybrid nature of my work.

NA It seems to me that your background is riven with lines. The line of apartheid. The line of partition, which tore India apart and gave birth to a new country, Pakistan. Lines divide, they fragment, they exercise a violence of their own. I see this in your work. At the same time, your art, fashioned from vernacular bric-a-brac drawn from motley sources, gives lie to the myth of purity, of being from one side of the line. It makes sense that you were deeply affected by the art of Gandhara, itself Buddhist but inflected with Greco-Roman influence. I am trying to conjure a Buddha with Apollo’s face.

HB The lines in my art are absolutely about combining my emotions with a highly sophisticated approach to materiality. I believe there’s no such thing as one side of the line. Notions of purity, nationalism, and patriotism are extremely disturbing and heinous to me.

NA I read a piece in the Times recently—maybe you saw it too—about how Karachi’s old Empress Market, named after Queen Victoria, was soon to be razed for beautification. The article included a crucial detail: the market had once been the stage for executing dozens of South Asians who had risen in mutiny against the occupying British. After independence, the market drew people from all over the city. It was a hybrid space, not unlike your own work—a mishmash of histories, textures, instincts.

HB I used to shop for groceries at Empress Market with my mother when I was young. One of my favorite sections was where the butchers sold fresh meat. I was fascinated by how they carved up the animal in the most beautiful way, with knives only. The market was a place full of flies and stray cats, dogs waiting for a scrap. And yes, gentrification is a domestic form of colonialism.

NA You were taken by the scrap market: that seems apropos. Your use of material is idiosyncratic, collagistic. The materials themselves have the quality of evoking refuse, detritus, the leftover and discarded. Can you tell me a bit more about the materials you use, where you source them and when and how this tendency began? Were you always working in this way?

HB I started using found wood and cutting up printing proofs to make assemblages when I was an undergrad at the Rhode Island School of Design. I was interested in painting on hard surfaces so I scavenged from the garbage. If I liked something I’d use it. Later, when I moved to New York, I furnished my apartment with things other people had thrown away. I had no money so I adapted my work to include found and cheap objects for both the armature and the surface. One thing led to another. So I guess you can say I always liked working in this way.

NA Your works are often bruised, for lack of a better word, betraying the marks of their making. There’s no commitment to bravura artifice. Can you tell me about this mark-making, these tattoos of time and place?

HB The hand is consciously very present in my work. Showing my skill, or lack of, is very much part of my process. The carving, scratching, and painting on the sculptures has evolved a lot over the past few years. My interest in expressionistic mark-making in the work of painters like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Georg Baselitz has merged with the use of found materials and combines that you might see in Robert Rauschenberg and David Hammons. I should add that African art is the one consistent genre that I return to again and again.

NA There’s something of African funerary sculpture in your work, too. And like Rauschenberg and Hammons, there’s a humbleness to the materials you use. Like them, your imprimatur, or fingerprint, is ever present. The marks you make almost feel like hieroglyphics to decode.

HB Or let’s say a private language—made-up messages to keep evil at bay.

Artwork © Huma Bhabha; photos: Matteo D’Eletto, M3 Studio