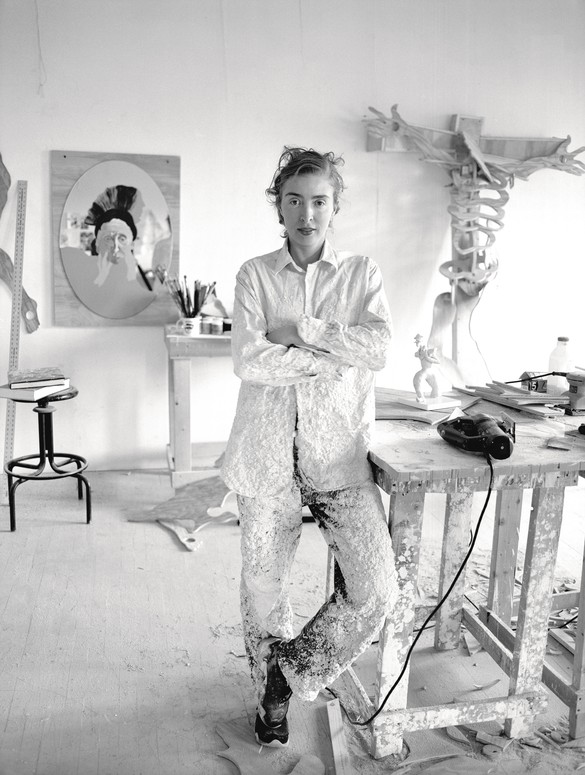

In richly detailed sculptures and multipart installations, Rachel Feinstein investigates and challenges the concept of luxury as expressed in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, in the context of contemporary parallels. By synthesizing visual and societal opposites such as romance and pornography, elegance and kitsch, and the marvelous and the banal, she explores issues of taste and desire. Photo: Markus Jans, Architectural Digest © Condé Nast

Alan Yentob has held many prestigious positions at the BBC. In addition to these various roles, he is on the boards of the South Bank and the International Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. He is also chairman of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London.

Alan Yentob I want to ask you about your early life and the influence of your family—you have a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, and when you went to university you chose to study art and religion.

Rachel Feinstein Yes. My family is really the source of my whole vision. My father was a classic second-generation immigrant; his family came from Vilnius, he grew up in Brooklyn, and his grandfather only spoke Yiddish and would go to shul every day. My father was remarkably intelligent and worked hard, even from a young age, cleaning sheets and doing laundry. His father never finished sixth grade and he decided he wanted something better for his life. So he worked hard and went to Brooklyn College.

After that he went on to SUNY Syracuse for medical school, and it was there that he met my mother, who was this eighteen-year-old freshman from upstate New York—five-foot-ten-inch blonde Irish-German Catholic girl [laughter]. They completely fell in love at first sight and that love affair has continued throughout my whole life. They’re total opposites, but through these different backgrounds they each almost became the other person after fifty years of marriage. My mother makes the best matzo ball soup—I mean, really incredible—and my sister ended up marrying a practicing Jew and her daughter had her bat mitzvah in Israel.

I was always curious about these two backgrounds I grew up in the middle of. I went to Temple Beth Am for elementary school and I was baptized Catholic, secretly, by my mom. Later, in Miami, I didn’t know what was going on [laughter]. And now, according to Claudia Gould, the director of the Jewish Museum in New York, my mom told her that she converted and she’s actually Jewish. That was the first I’d ever heard of this. I still don’t know what the real story is, to tell you the truth.

AY This is fascinating. That thing about opposites, your parents Catholic and Jewish, reminds me of your own interest in the paradox of fairy tales and fantasy, where there’s a dark side to these genres.

RF Yes, yes. You need darkness to show light. All fairy tales originated from much more gruesome and sinister stories than we know now.

AY Your grandmother was an artist as well, correct?

RF Yes, a painter. She was my mother’s mother. Her husband died when she was in her forties, and she stayed single the rest of her life; she was the unusual creative spirit in my life. She had an orange VW bug and she drove it till she was ninety-five years old.

AY Wow, just like Mel Brooks, ninety-three and he’s still driving a car.

RF Exactly [laughter]. She’d drive me around Miami, and at that time, in the 1970s and ’80s, it was nothing like it is now. There was no culture whatsoever. There was no ballet and almost zero art museums. There was the Bass art museum, and this old art theater on Collins Avenue. They would play old movies, experimental films, as well as more mainstream stuff. My father brought me to see Koyaanisqatsi [1983], the Philip Glass/Godfrey Reggio film, when I was like twelve years old. I’m still amazed—I don’t know how he learned about the film, or thought to take me, because he had really no art education whatsoever. It was definitely one of those key moments. I truly believe that every artist, writer, and filmmaker—it all stems from those pivotal years when you’re a child and you’re soaking it in.

AY I absolutely agree. I’d love to talk about your abiding interest in materials. From even your earliest artworks, there’s a concern for the history and specifics of whatever material you’re using. In your work with ceramics and plaster, the hands-on dimension of using those materials also seems, to me at least, to be an important part of your process.

RF There are a lot of films of me and my sister when we’re really young, and I saw them for the first time since childhood maybe ten or fifteen years ago. In one of them my sister’s in the pool with all of these neighborhood kids and they’re jumping and they’re playing, and then I’m in the corner cutting up a box; I’m just trying to dismantle it and then restack it together to make a sculpture.

And I remember there were some old shoes being thrown out, and my father being a doctor would have really cool, weird plaster bandages and alginate, a dental-mold material. I have no idea why they were around the house, but I’d mix it all up, and I covered it all on this shoe, and then I painted the shoe in all these colors. I brought it to school and they thought it was so amazing that they submitted it to the Miami-Dade county fair, which is a really Southern thing where people bring livestock in and get prizes. I won an award for that shoe! [laughter]

AY This element of play is still very much part of your work today, wouldn’t you say?

RF Very much so. And also the influence from Disney World. I’ve tried to count how many times I’ve been to Disney World in Orlando, and I honestly got to fifty and gave up trying to remember. I’ve been there so many times that I know where all the secret doors are that all the characters go into.

If you graduate from high school in Florida, they have something called “grad night” where every single graduating senior in the state gets to go to Disney World from 9pm till 6am It’s an extraordinarily weird and amazing experience, totally surrealistic. I heard that this person was on acid and really freaked out—the staff took him into a holding cell that you don’t even know exists underneath one of the rides. They went down a little hole and then disappeared until the next day. I mean, imagine having that happen to you when you’re seventeen. It informed my worldview. That’s why I think life is big and full of surprises—you can try to have everything and do everything and not limit yourself, but you never know what will happen. And I think life is out there for the taking and you might as well just try. You only live once, you know?

AY The other thing that drives you, and I think it’s the big C in creativity, is curiosity. You were obviously a child who just got immersed in all these things; now there’s another side to this—the Disney World angle, Grimms’ fairy tales, where you’ve got the dark side and the light side. These are things that obviously preoccupied you. Where did you get your interest and curiosity about baroque and rococo art from?

RF Growing up, I didn’t have the huge love and knowledge of art history that I do now. Even as an art student, my initial belief was in making art from an unconscious place deep inside. When I attended Skowhegan, in Maine, I had Kiki Smith as a teacher, and earlier Ursula von Rydingsvard and Judy Pfaff as my teachers at Columbia. They were huge influences on me, and at that moment in the early 1990s, Kiki was showing a sculpture of a woman on all fours with this big turd coming out of her—I mean, I could not believe it.

That visceral, nasty side of making art, that was where my first real energy came from. I had never seen that in art before, especially coming from a woman. I think it appealed to me, in part, because of my dad’s background in medicine. My dad would have this dermatological magazine called Cutis lying around the house while I was growing up. There were always intense pictures of people with syphilis or various other ailments, it was literally a skin magazine [laughter]. So Kiki’s art showing the visceral quality of being human, instead of glossing over everything, really spoke to me. I followed suit and was making work that was more physical and female oriented. I’d make alginate casts of my vagina and my anus and I’d wear it as jewelry out for the night.

AY And there was your Sleeping Beauty performance, right? You slept in Exit Art, a public gallery, for a week.

RF Yes. I was working at a bar in those days, the early ’90s—I had bleached white hair and I’d wear this pink ’50s underwear with this big black pubic hair coming out, and I’d walk around the bar like this. It was so incredible. It was right next to the New School. I enjoyed being a spectacle. At Exit Art I made a gingerbread house and I staged my performance through a window in the sculpture, sleeping under a humping castle. I’d sleep in the gingerbread house every night after the bar job, so I’d come in probably around 5 in the morning. I’d have to close the bar up at 4, count the money, count the bottles, sneak into this gallery, and go to sleep, but I couldn’t sleep because it was so weird, so I’d have to take sleeping pills. And people would look through this frosted-glass window to see me sleeping. The very first night, a man came up to me and said, “You look like John Currin’s paintings.” This was 1994 and I’d never heard of John Currin, didn’t know who he was, and I said, “Well, whatever,” and went on my way. And he kept calling me on the pay phone at the gallery to try to get me to meet him. It was so bizarre. So I finally stopped taking his phone calls.

AY The word is “stalking.”

RF Yeah. And the other thing about this man was, this was early September when all the galleries had just opened up, and September in New York can be very hot, and he was wearing full leather: a leather vest, a long leather jacket, leather pants, and high leather elevator shoes. And unbeknownst to me, he got John’s number from the White Pages, called him up, and said, “There’s this girl and she looks like she stepped out of these paintings that you’re making right now.” So John being John walked right over to SoHo. He was very close by. He was still wearing his painting clothes. He walked into the gallery and our eyes locked, and there’s about fifty people, and I walked over to him and I kissed him on the lips. Really, it’s really strange, and I don’t know why. We went out that very night and we’ve been together ever since.

AY That is a great love story. So you get together with John and he’s an artist and you’re an artist. You have different approaches but you’re often interested in similar themes.

RF Yes, you asked me earlier about baroque and rococo influences and how they found their way into my work, but I got sidetracked. So basically I was making this more subconscious type of work, and then I felt like I got all of that out of me, and it was gone, and I didn’t know what to do anymore. I was a little bit empty. When I kept finding myself lost, John would say, “Let’s go to the Strand bookstore together.” I remember focusing on the first image I saw in a rococo-period book, which was a Mars and Venus porcelain by Royal Derbyshire. After seeing that I made a small sculpture called Waterfall [2001]. I included it in a show and my dear friends Tobias Meyer and Mark Fletcher said, “You have to let us take you to see all the German rococo.” So we did a trip in November 2000 to see Würtzburg and Wieskirche and Nymphenburg, and that’s when everything kind of clicked into gear.

AY There’s another side we should talk about before we finish, which is being a mother and also being an artist. How did you make these things work?

RF Fitting into my belief in a world of dualities, I think that’s the greatest and strongest duality for me. They work against each other and they work with each other. I don’t think I would be capable of the scheduling and arranging what’s needed to make the work I make now if I didn’t have three children. I was a person who used to sleep until 12:30 in the afternoon, and everything does change overnight when you have children. To be a parent you have to grow up. There’s been a history of allowing artists to get away with very bad behavior, because of this belief that the egocentric need to put forth your own vision into the world is so strong that you’re allowed to be a horrible human being and act like a spoiled child as a grown-up. But that’s the opposite of being a good mother. I’m in my studio, I have three young men working for me and I have to tell them what to do, but I want to take care of them too. It’s completely conflicting at every moment of my life; so now I’m trying to use that as my strength.

Artwork © Rachel Feinstein