Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

“Bildung” is a useful German word meaning a gradual process of self-cultivation, intellectually and aesthetically as well as morally (in the sense of character formation). It came to mind when I viewed Georg Baselitz’s exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. Containing nearly one hundred paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures, this unforgettable exhibition—the first by a living artist in the Accademia—focuses on the works Baselitz made before and after the formative months he spent in Florence in 1965 on a Villa Romana fellowship, the oldest German visual-arts prize. The title of the show, Baselitz – Academy (coined by the artist as a sort of pun on “Accademia”), alludes to the difference between self-education and formal or academic teaching but also to the role that the latter can play in the former. It is a happy coincidence that the galleries devoted to the exhibition were once occupied by the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, the art school where the Venetian abstract painter Emilio Vedova, one of Baselitz’s heroes, taught from 1975 to 1986.

You have to consider that the venue is an academy, in Venice, during the Biennale . . . you can’t show up with anything slipshod. The Gallerie dell’Accademia is not the German Pavilion, where contemporary work is shown; here it’s about history as a rule. . . . For me the Gallerie dell’Accademia is a chance to show things that have been important in my life, but have not been so clearly appreciated as yet—the portraits, the early nudes, the negative pictures.1

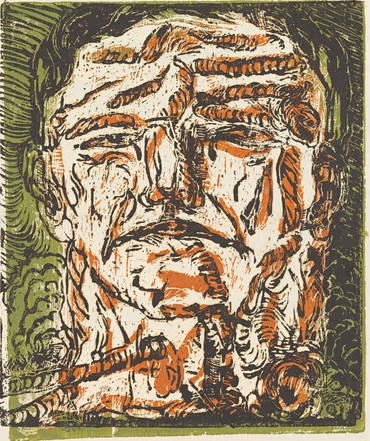

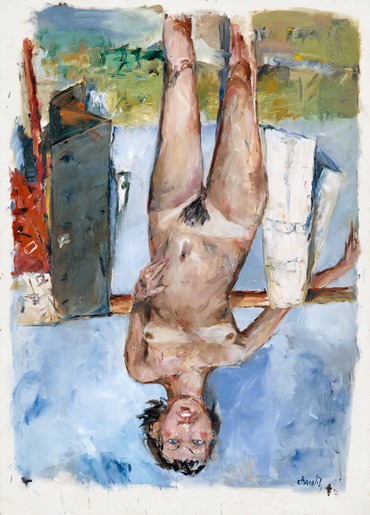

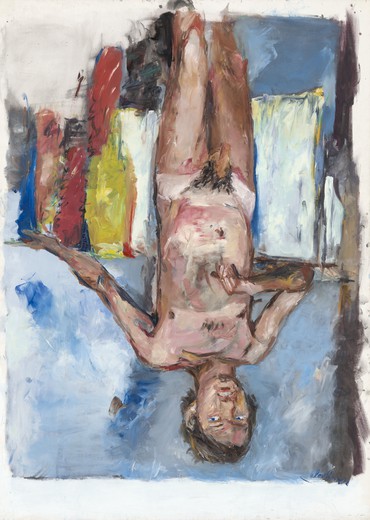

The three larger galleries in the show are dedicated to a spectacular display of portraits and nudes from two especially vibrant and productive periods of Baselitz’s oeuvre: 1969–77, the first “upside-down” decade; and 2004–12, including the series of “negative” pictures that Baselitz mentions above in his interview with the exhibition’s curator, Kosme de Barañano. In the four smaller rooms and in the corridor leading up to the entrance, Baselitz’s long and fruitful engagement with Italian art is explored in depth, largely through works on paper.

Baselitz’s first introduction to art history came in 1955, when, as an ill-prepared seventeen-year-old in Kamenz, East Germany, he and the rest of his school were taken to Dresden, sixty kilometers to the southwest, to welcome home the old master collection of the city’s Gemäldegalerie alte Meister on its return from a decade of forced exile in the Soviet Union. The following year he took lessons in drawing at his local community college (Volkshochschule) before applying to the Hochschule für bildende und angewandte Kunst (Academy of Fine and Applied Arts) in East Berlin. His uncle Wilhelm, a Dresden priest, had earlier encouraged the young Baselitz to paint by arranging for him to be given paints, brushes, and a palette and by introducing him to the paintings of the nineteenth-century Saxon realist Ferdinand von Rayski. Baselitz also recalled recently his excitement at discovering a book on Italian Futurism when he was fifteen or sixteen:

I was in the library that I often visited in my town, Kamenz, which had been purged of all such art and literature by the Nazis and then the Communists. You couldn’t find anything there anymore that disturbed, that was controversial. But still, I found a book, which I remember was called Il Futurismo . . . , with some black-and-white reproductions in it.

I had never seen anything like that before, and because it was all in black and white, I was only able to picture some of it. Yet I immediately started working in this fashion, with drawings, very large drawings, and I thought—and this is the strange thing about it—that now I was up to date, that I was a modern artist.

Now I know that I was mistaken.2

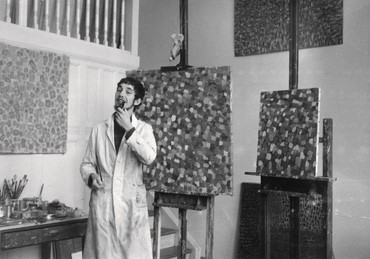

In East Berlin, Baselitz studied painting under Walter Womacka and Herbert Behrens-Hangeler, the former a Socialist Realist to his fingertips, the latter a modernist who was out of favor with the Communist regime and was restricted to teaching painting technique and color theory. Baselitz remembers it as good training, even though he survived only two semesters of a six-year course before being expelled for “socio-political immaturity.” In addition to painting, life drawing, and still life drawing, there were classes in wall painting, calligraphy, art history, and political history (i.e., Marxism-Leninism), the latter compulsory. Art history began with the nineteenth-century realist Adolph von Menzel, on the grounds that he had painted workers and industrial subjects and was therefore a forerunner of Socialist Realism. As an eighteen-year-old from the provinces, Baselitz knew no better. In the art-school library he found books on Pablo Picasso published in Czechoslovakia, but when he tried to paint like Picasso he was reprimanded by his teachers.

Baselitz’s move to West Berlin in 1957, to continue his studies under the tachist painter Hann Trier at the Hochschule für bildende Künste (Academy of Fine Arts), must have dealt him a profound shock. He not only had to unlearn much of what he had been taught in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) but his knowledge of twentieth-century art movements—Die Brücke, Der Blaue Reiter, Bauhaus, and so on—was nonexistent:

At the age of eighteen, I was completely ignorant, I had no information, I basically knew nothing. I literally lacked any knowledge of contemporary art or of the past.

. . . At the academy in West Berlin, I was an abstract, informalist painter, as one was supposed to be, like my teacher.3

Wasting no time in making up for such cultural deprivation, Baselitz began a crash course in European art. He started to visit the old master collection in West Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. Guided by Trier, he read the writings of abstract or nonobjective artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Vasily Kandinsky, Willi Baumeister, and Ernst Wilhelm Nay, many of whose theories (e.g., concerning pictorial harmony) he would reject. In 1958, at the art school where he was a student, he saw The New American Painting, a traveling exhibition of seventeen Abstract Expressionists, organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, shown together with a small retrospective of Jackson Pollock, who had died a couple of years previously. The two exhibitions were a revelation, but their impact on Baselitz was also confusing:

I had just come from the GDR and I had a picture model in my head of how art and society existed together. In my mind, the picture was not free; the picture served a function in society.

. . . And then I saw Pollock, [Willem] de Kooning, Sam Francis, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, and others in terms of freedom. The effect was overwhelming, but at the same time, you couldn’t breathe anymore. . . . And so I looked for someone who offered a bridge, and the one with whom I found it . . . was de Kooning. At least he had the artistic foundation of Picasso. . . . And yet, in the works that I made then, you cannot find any trace of de Kooning.4

The following year, Baselitz visited the second Documenta, the exhibition that more than any other proclaimed the ascendancy of abstraction in the West. In 1960 he traveled to Amsterdam, where he admired paintings by Rembrandt and Soutine, and in 1961 he visited Paris. He made drawings based on Pontormo’s Madonna and Child with Saint Anne and Four Saints in the Louvre—the first stirrings of his love of Mannerism—and started to take an interest in the work of artists and writers outside the mainstream: the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, for example, the poet Isidore Ducasse (the self-styled Comte de Lautréamont), and more-contemporary figures such as Jean Dubuffet and Antonin Artaud (originator of the Theatre of Cruelty, and a victim of schizophrenia). The angry, nihilistic “Pandemonium Manifestos” that Baselitz and fellow artist Eugen Schönebeck issued in Berlin in 1961 and 1962 clearly show the influence of Artaud’s writings and drawings. In the same period, Baselitz also discovered Hans Prinzhorn’s classic 1922 book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill), on the art of psychiatric patients. It confirmed him in his intuition that it was the tragically human but uninhibited language of madness and irrationality that would reinvigorate painting—a new kind of painting that would transcend the dichotomy between abstract and representational art, uniting elements of both: “the complete reinvention of the world, and of course of the picture. To no longer imitate nature but to paint a reality.”5

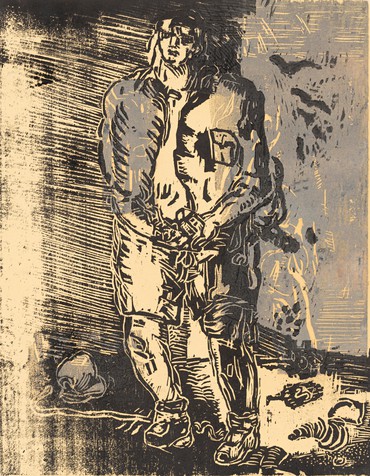

The connection between the imagination of madness and the unnatural, anticlassical forms of Mannerism was made in a book by Gustav René Hocke, Die Welt als Labyrinth (The world as labyrinth), first published in 1957. It prepared Baselitz for his stay in Florence in 1965. In Florence he was attracted to sixteenth-century Mannerism and was inspired to buy prints from this unfashionable period, especially chiaroscuro woodcuts. Their distorted forms, dramatic light effects, and heightened color contrasts influenced his own monumental figurative style. This is evident in the ironically titled “Hero” and “New Type” images that Baselitz made on his return to Berlin, works evoking childhood memories of war, destruction, and social breakdown in the rural part of eastern Germany where he grew up.

You could say that in Florence I began to study art history as an autodidact. The famous German Kunsthistorisches Institut there had catalogued only Italian art. Its people were very kind. . . . I was allowed to look at everything. And I have to say, that was a great period of education for me. If you find your own way and don’t have it mapped out for you, it’s better.

. . . [After] I had exhausted the entire Institut, so to speak, [I] began collecting prints.

. . . The art history of Italy, art history of Germany—that was what interested me. . . . But when an artist does art history, he doesn’t do it objectively. He asks himself: What can I take from this? What interests me? What do I need?6

For Baselitz, studying art history in this private way, visiting the Uffizi, making drawings back in his studio from reproductions, reinterpreting old master paintings, helped him mature as a person. In Berlin he had been, by his own admission, “a very aggressive type . . . a naive, oafish young man.”7

I was in a very poor state, completely adrift and disorientated. I had no religion, and no ideology. And I did not have what the École de Paris had, for example, what was referred to as “existentialism.” I simply reacted in a very violent and angry manner. The general thrust of my reaction was ugliness.

. . . I found everything so lousy, and I tried to show it. . . . This is why I painted the P.D. pictures. I did not paint them as a masochist or as an onanist; I painted them as someone who desperately wanted to be seen.8

It was the P.D. (Pandemonium) paintings, and related canvases such as Die Große Nacht im Eimer (The Big Night Down the Drain) of 1962–63, that caused a scandal and got Baselitz and his dealers into trouble with the law. Die Große Nacht im Eimer shows a male figure whose body appears to be decomposing, dressed only in shorts, masturbating his disproportionately large penis—a gesture symbolizing futility and alienation that is found in other works by Baselitz of the early-to-mid-1960s. A couple of paintings were confiscated by the police, the legal process dragged on for two years, and Baselitz did not get the works back until 1965, when he was in Florence. He was bruised by the whole experience: “I felt a fairly strong social pressure. That induced me to seek a substitute. And that substitute was art history in museums.”9

Initially, the subjects of Baselitz’s pictures had no source in reality; they were nothing to do with nature or illusion but were, in the artist’s own word, “inventions”: “You reject the model, the portrait model, the nude model, the landscape model.”10 But all this was to change in 1969.

Beginning with the [first upside-down] portraits there was a model, and I had photos. I thought to myself: You can forget drawing in this realism sense. That’s no use, others have done it better. So I took Polaroid photos and used them like Pop art, like [Andy] Warhol. And then I painted these photos. I didn’t print them, or screen them. . . . I simply painted them.11

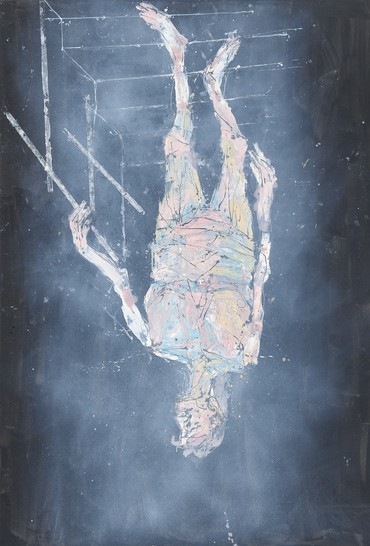

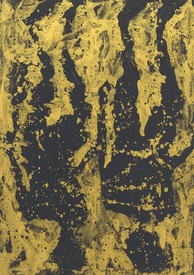

The Accademia includes a striking series of eight of these half-length upside-down portraits of Baselitz’s friends (all 162 × 130 cm, or 63 ¾ × 51 ¼ inches), executed in a naturalistic idiom but with an expressive painterly touch. As “demonstrations of absurdity” (the artist’s phrase), they occupy an important place in Baselitz’s oeuvre in that they are the first paintings to draw attention to the autonomy of art—to the painting as a self-contained object—without completely jettisoning tradition.12 His ambition to deconstruct figurative painting is further developed in the full-length nude self-portraits and nude portraits of his wife, Elke, that followed in the 1970s, also well represented in the Accademia show. Baselitz painted some of these with his fingers: “I . . . scoured the canvas, so that it would become as cold as possible. For the background I took a large amount of white and then worked with cold colors.”13 A similar alienation effect (to use Bertolt Brecht’s celebrated term) characterizes the “negative” paintings from 2004 onward, the first of which was based on a computer printout of a photograph of Elke with the colors reversed. In addition to portraits, Baselitz applied this technique to reproductions of Socialist Realist paintings from books on Soviet art that he had been brought up with in the GDR.

A coda or climax to the exhibition is provided by a pair of recent canvases that Baselitz showed me in his studio in Bavaria this winter, enormous full-length naked portraits, over fourteen feet high, of the artist and Elke, both titled Ankunft (Arrival). In each painting a figure is seen tentatively descending a staircase (echoes of Marcel Duchamp) against a black background. Here the distancing device is one of flatness, a complete absence of modeling in the way the figures are constructed. Since the early 1990s Baselitz has painted on unstretched canvas laid out on the floor. He uses stencils or templates to achieve sharp contours and to stop the paint from running, and thins the paint often with a mixture of turpentine and linseed oil. Consequently the figures seem to float, shadowless and almost transparent, like ghosts. As poignant reflections on the frailty and vulnerability of old age, these two recent portraits can also be said to conform to the concept of Bildung, which includes a crucial element of self-awareness.

My thanks to Georg and Elke Baselitz for their replies to my questions in conversation (Ammersee, January 15, 2019) and to Detlev Gretenkort, Julia Westner, and Leeor Engländer of the Baselitz Archive and Studio in Munich.

1Georg Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz in Conversation with Kosme de Barañano,” Baselitz – Academy, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian, 2019), p. 252.

2Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz and Okwui Enwezor in Conversation,” in Georg Baselitz: Jumping Over My Shadow, exh. cat.(New York: Gagosian, 2016), p. 53.

3Ibid., pp. 53, 54.

4Ibid., pp. 54–55.

5Ibid., p. 56.

6Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz in Conversation with Kosme de Barañano,” pp. 242, 244.

7Ibid., p. 243.

8Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz and Okwui Enwezor in Conversation,” pp. 55–56.

9Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz in Conversation with Kosme de Barañano,” p. 244.

10Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz and Okwui Enwezor in Conversation,” p. 55.

11Baselitz, in “Georg Baselitz in Conversation with Kosme de Barañano,” p. 252.

12Ibid., p. 253.

13Ibid.

Baselitz – Academy, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, May 8–October 6, 2019

Artwork © Georg Baselitz; photos: Jochen Littkemann, unless otherwise noted

![Georg Baselitz, Ohne Titel (nach Pontormo) (Untitled [after Pontormo]), 1961, watercolor on paper, 12 ⅛ × 8 ⅝ inches (30.7 × 21.8 cm)](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/essay-baselitz-bildung/UR9p0HxyJ5PR_585x1170.jpg)