Berit Potter is assistant professor of art history and museum and gallery practices at Humboldt State University, where she oversees the Museum and Gallery Practices Certificate Program. Her current book project, Widely Curious: Grace McCann Morley and the Origins of Global Contemporary Art, examines the career of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s first director and her pioneering advocacy for global perspectives.

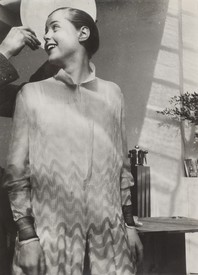

In 1960, twenty-five years after taking the helm at the San Francisco Museum of Art—“Modern” had yet to be added to its name—Grace McCann Morley summed up her vision of the art museum, describing a dynamic space that offered “the revelation of a new experience, a new kind of world, a new way of living, really.”1

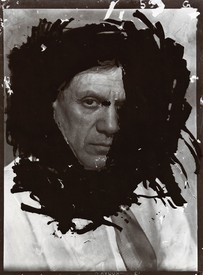

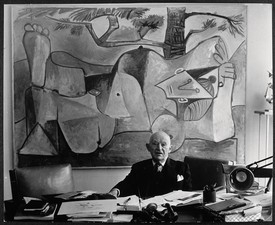

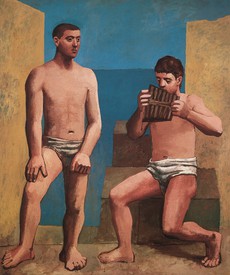

Of the staggering seventy to one hundred exhibitions that Morley staged in each of the museum’s earliest years, perhaps none bore this out more than Picasso: Forty Years of His Art. Morley brought the exhibition to San Francisco from New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1940. Such was the show’s intensity for the 1,300 visitors who attended on the last day that many sat down in the galleries and refused to leave when the museum tried to close its doors at 10 p.m.2

Morley had been raised in rural St. Helena, California, and attended the University of California, Berkeley, before her passion for languages, literature, and, above all, art inspired her to migrate to the Sorbonne, where she earned a doctorate in literature and art in 1926. After returning to the United States, she served as the first general curator of the Cincinnati Art Museum, then in 1933 made her way back to the West Coast. Two years later she established the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA) in its first permanent home, on the top floor of a beaux arts edifice across the road from City Hall.

As founding director of the fledgling museum, Morley’s first order of business was to broaden San Francisco’s experience of modern art. The city’s de Young and Legion of Honor museums—which opened in 1895 and 1924, respectively—were what Morley called “general art museums,” not exclusively dedicated to modern art. Noting the city’s cultural isolation, particularly that “artists were ten or fifteen years behind the movements of their time, simply because they didn’t see enough of what was going on in art,” Morley was eager not only to build on local interests but also to collaborate with institutions across the country.3

Morley’s relative historical obscurity today is particularly paradoxical given that she brought regional, national, and global recognition to many formerly obscure artists.

Immediately noting the region’s passion for Diego Rivera, who had created his first murals in the United States in San Francisco in 1930 and 1931, Morley worked to expand the public’s interest in Latin American art beyond Mexico. In 1942 she organized the first survey exhibition ever dedicated to modern Latin American art, a show that traveled throughout the country in various forms for the better part of the decade, and she ultimately developed an important early collection of modern Latin American art at SFMA, including works by Eduardo Kingman, Amelia Peláez, Emilio Pettoruti, and Joaquín Torres-García.4

Prior to the Picasso show, Morley had challenged the museum’s audiences with other groundbreaking exhibitions from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, including the pivotal Cubism and Abstract Art (1936) and Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (1937). Indicative of the critical reception of her daring program is the San Francisco Chronicle’s description of the latter as “a cross between a three-ring circus and a chamber of horrors.”5

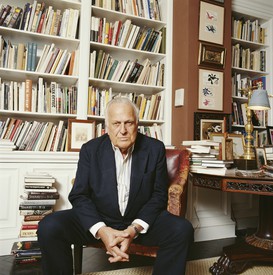

Morley’s relative historical obscurity today—she is far less known than her East Coast colleague and friend Alfred H. Barr, Jr., MoMA’s founding director—is particularly paradoxical given that she brought regional, national, and global recognition to many formerly obscure artists. At a time when many East Coast institutions still had their eyes trained on Europe, Morley gave numerous Abstract Expressionists some of their earliest museum exhibitions. Presentations of work by Arshile Gorky, Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Robert Motherwell all took place at SFMA between 1941 and 1946. Under Morley’s direction, the museum also acquired significant early paintings by Pollock and Rothko.

Many of these exhibitions and acquisitions came about through Morley’s close collaborations with figures including gallerist Peggy Guggenheim and mosaicist Jeanne Reynal. (It was Reynal who encouraged Morley to borrow Guggenheim’s Pollock show in 1945.)6 Indeed, Morley’s enthusiasm for collaborating with artists, collectors, gallerists, and museum colleagues—many of them women—helped her to build a diverse collection and exhibition schedule at SFMA. Her position as a female museum director working on the West Coast undeniably gave her a curatorial perspective different from that of many of her male colleagues to the east.7 While MoMA organized its first one-woman exhibition in 1942, SFMA had presented more than forty solo shows dedicated to women by 1940, during its first five years.

Morley’s ardent support for young American artists included highlighting individuals from the West Coast at a time when the region was largely overlooked. This dedication is best exemplified by her traveling exhibition Pacific Coast Art, which debuted at the third São Paulo Bienal in 1955 and brought international recognition to Ruth Asawa, Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, and many others. Morley also encouraged museum colleagues to visit California. As she wrote to Barr, “I have a feeling that until one knows the ‘backyard’ of the United States, west of Chicago, one does not know the whole picture.”8

Morley was a tireless evangelist not only for art and artists but for the role of the museum, especially as a powerful tool for social and political change. From 1947 to 1949 she took a leave of absence from SFMA to serve as the first head of unesco’s Museums Division (later ICOM, the International Council of Museums) and founded the international journal Museum. After leaving SFMA, in 1958, she worked briefly at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York before accepting a position as the director of the National Museum of India in 1960 and later leading ICOM’s Regional Agency for South and Southeast Asia.

All this, though, came after she had left an indelible mark on California. Despite criticism and pushback, Morley had persevered, by 1955 transforming San Francisco into what Time magazine called “one of the nation’s most enthusiastic strongholds of modern art.”9

“And that’s what art is, you see,” Morley explained, “it’s a broadening of experience.”

1Grace McCann Morley, quoted in Suzanne B. Riess, “Grace L. McCann Morley: Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art: An Interview,” 1960, University of California, General Library/Berkeley, Regional Cultural History Project, p. 178. The museum was renamed the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1975.

2Susan Landauer, The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996),

p. 30.

3Morley, quoted in Riess, “Grace L. McCann Morley,” pp. 36, 106.

4See Berit Potter, “Building a Model of Diversity: Grace McCann Morley and Collecting Modern Latin American Art in San Francisco,” in Edward J. Sullivan, ed., The Americas Revealed: Collecting Colonial and Modern Latin American Art in the United States (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2018).

5Alfred Frankenstein, “Comments and Cautions Evoked by the Year’s Most Sensational Show,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 8, 1937, p. 4D.

6Jeanne Reynal had just purchased Jackson Pollock’s 1941 painting The Magic Mirror from Peggy Guggenheim. See Potter, “Gathered Another Way: Early Surrealist Exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art,” in The Space Between: Literature and Culture 1914–1945 14 (2018). Available online at http://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol14_2018_contents (accessed September 24, 2019).

7Megan Martenyi explores the possibility of Morley identifying as queer in her essay “Wide Open Publics: Tracing Grace McCann Morley’s San Francisco” (SFMOMA, August 2017). Available online at https://sfmoma.org/essay/wide-open-publics-tracing-grace-mccann-morleys-san-francisco/ (accessed September 24, 2019).

8Morley, letter to Barr, January 23, 1952, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Papers, 1.124.

9“Art: Twenty Years of Grace,” Time, February 28, 1955.

10Morley, quoted in Riess, “Grace L. McCann Morley,” p. 178.