In his photographs, Roe Ethridge uses the real to suggest—or disrupt—the ideal. Through commercial images of fashion models, products, and advertisements, as well as intimate moments from his own daily life, he subverts the residual authority of established artistic genres such as the still life or the portrait, merging them with the increasingly pervasive image culture of the present. Photo: Albrecht Fuchs

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and critic. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications, and he has contributed essays to museum and gallery catalogues. Sargent has co-organized exhibitions including The Way We Live Now at the Aperture Foundation in New York in 2018, and his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, was released by Aperture in fall 2019. Photo: Darius Garvin

Antwaun Sargent So, how are you doing, Roe?

Roe Ethridge Oh, you know. It’s weird, and then it’s not weird. And then that makes it even weirder.

AS Exactly, that’s how I feel too: What am I supposed to be doing in this moment?

I wanted to jump in and ask how, as someone who has been working in an “art and fashion” space—a space between the commercial and the conceptual—for a very long time, you started that process of breaking down the distinctions that have been made between art photography and commercial photography?

RE I guess I could trace it back to being interested in Andy Warhol and Irving Penn when I was in high school. For whatever reason, Pop imagery and Penn’s Camel cigarette packs just made sense to me as a sixteen-year-old in suburban Atlanta.

There was a show on MTV for a minute called Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes.

AS Oh, right. Yeah.

RE It seemed kind of lame, but also completely free and commercial. There was very little art in it, you know what I mean? [laughs] I think that blew my mind. I was so open to taking it all in.

At the same time my dad had these photography books and I was discovering Lee Friedlander. So it was this weird thing where in my world there was both Friedlander and Warhol. There was something about the mirrors that they put up—looking back, I can say it’s like mirrors, but it’s also compositional; there’s something formal about it. And the persona was so droll.

Back in the 1980s, identity politics were really coming to the fore. And being in art school at that time, I had to ask the question, Well, who am I? There was something about stock photography and the generic that felt like this was the script that I was supposed to pick up, resent, reject, participate in, whether I wanted to or not. It was the lightbulb going off: this sort of generic Methodist, Southern middle class was my stuff.

I would go to the grocery store and spend an hour at the magazine stand just looking at fashion photography. It’s like that was my Instagram in 1990—going to Big Star and looking at magazines [laughs]. You’d just flip through and consume these images for an hour, lost in Vogue, Elle, Mademoiselle, Bride’s Day. And it was all interesting to me.

After I graduated from art school, I assisted catalog photographers. It’s the main image industry in Atlanta, because it’s a cheap place to have a big, shedlike structure to pump it out. So I got the lowest-common-denominator fashion experience, but it was also like producing stock photography. I think that’s when I really started to think, What if I worked as a commercial photographer and made the images that Richard Prince is appropriating? You know what I mean?

It’s a thing where one image could slide from one context to another. If it didn’t have a caption, if it wasn’t historically contained, it could do multiple things.

Roe Ethridge

Then when I moved to New York in 1997, I was assisting and almost immediately I got a job for the New York Times and another one for Allure, and I was like, What is going on here? I thought I had to have a union card or something. It felt like I was doing something illegal, almost, both from the commercial side and as an artist. Like I was fooling around. But at the same time I thought, “This is what photography does—it’s different from painting or sculpture, and it’s also different from film or TV.” It’s a thing where one image could slide from one context to another. If it didn’t have a caption, if it wasn’t historically contained, it could do multiple things.

AS When was the moment for you when these weren’t actually separate practices, when it was all the practice of one artist? Because all the way through the ages, there was this deliberate separation, right? “These images are my art images and these images help me survive and pay the bills.” What image or moment made it all connect?

RE I would say it’s probably the portrait of Kathryn Neale from 1999. I had been hired by Allure to shoot some front-of-book beauty stuff, and my first assignment was how to put on lipstick. When Kathryn showed up to the shoot, her lips were chapped; it’s January, and they’re completely chapped. This was before Photoshop was ubiquitous, so the photos were going to have to be airbrushed. I was so overwhelmed in general, and then to have this obstacle—I think it added something to the energy of the whole thing.

But when we were taking the pictures I realized that there was this exchange going on: she wanted to look good and she wanted to be famous and she wanted to get paid, and I wanted my pictures to look good and I wanted to get paid and be famous too. We were both working toward this thing, in almost a collaborative way. I didn’t know what I was doing exactly, but I was sort of telling dumb jokes, because I thought what I could bring to the table with beauty photography was something more human—you know, as an artist, almost disrupting the flow, and not just having a perfect picture. It’s that Warholian thing—what does he call it?

AS The idea that everybody’s in on the picture making?

RE Yeah, that collaborative complicit thing—you know, this is not a street photograph; we’re producing it together. But there’s also something about the exactly wrong thing, that Warholian exactly wrong.

all of a sudden I had found the path. It was this comment on commerce, the collaborative complicit thing between the two of us. And the power of that image was like, “This is it.”

Roe Ethridge

Afterwards, I had a Polaroid from the shoot sitting in my studio, and my conceptual art project was over there on the table. I was working on this American version of German objective photography at the time. I was super bored with that, but you know, I wanted to be considered a smart artist. And every day the Polaroid was taunting my conceptual art project, saying, “This picture that you took for Allure had no thesis, and it’s better than the entire project that you’ve written about, that you’ve been the smart artist about.” I went back through the negatives and found one where Kathryn is laughing at my stupid joke, and I thought, “That’s the best picture I’ve taken all month.” I printed it up, and all of a sudden I had found the path. It was this comment on commerce, the collaborative complicit thing between the two of us. And the power of that image was like, “This is it.”

AS Fast-forward a bit, and you make the Andrew W.K. image. For me, I knew that image way before I knew who you were as a photographer—thirteen-year-old me, growing up in Chicago, seeing this image everywhere. It was just such a bizarre image for that moment. It broke through on the levels in which you’re talking about—it was an album cover image, and there was a function for that, but it was also a mirror, where you’re looking at this image and you’re thinking, “Well, what is this saying about me? How is this potentially a representation of my teenage angst?” [laughter] When you talk about the construction of that image and what you as a photographer were trying to go for, it wasn’t just album art—

RE Right. I met Andrew W.K. at a Fischerspooner gig when I was sort of the band’s in-house photographer. We started talking, and he said, “Let’s make a picture.” At that time he was just playing a keyboard onstage and singing. But there was something to him that was self-possessed. It felt like this would be a collaborative portrait—that mode where the subject brings so much to the image and I need to set up my little spider web to capture whatever it is.

Andrew had a couple of ideas about what he wanted to do. I think he brought an axe—it was going to be a kind of heavy metal picture, you know? I had set up lights and he showed up with what he wanted to wear. And then he went into the bathroom and came back out with this full-on bloody nose, blood everywhere. I’m like, okay, great. We started taking pictures and I said, “Let’s do some where you’re just looking through the camera, looking through the lens, no gesture.” And that was the magic moment. The taking away of the heavy metal trope and having a straight, nonexpressive gaze—almost like a Thomas Ruff, like a passport photo, except that it had this extreme situation happening [laughs].

There wasn’t any intention for the image when we made it, and later Andrew decided he wanted to use it for the cover of his album [I Get Wet, 2001]. I think he retouched the shirt, changing it from a basketball jersey to his signature white t-shirt thing. We were getting all ready to go, and then 9/11 happened. And we thought, What does this mean now? The context had changed. But to the record label’s credit, they kept it and said, “Actually, we think it’s an inspiring image, in a way.”

When you saw it in Chicago, did you see the blood? Or was it censored?

AS I think I saw it with the blood.

RE Because in some places it was covered with a sticker so that you couldn’t see the blood [laughs].

At the same time that the record was being released, the photograph was in a show in London, at the Barbican Centre [The Americans: New Art]. There was no coordination at all; it was total serendipity. The 24 × 30 inch print was hanging in a walnut frame inside the gallery, and when you walked outside there was a poster of nearly the exact same image all over London. It was crazy—this thesis that I’d been operating on wasn’t just theoretical anymore, it was literally happening: The image got made. It wasn’t named; it was just a picture. And then it got named as a cover. And it got named as an artwork. And it got promoted, so now it was a public image. It wasn’t just in the art world or in the record store; it was ubiquitous. I’d say that was the first time that something went—in that pre-Internet time—

AS Viral.

RE Yeah, if you want to say that—you know, where it was ubiquitous. Even if people didn’t know who Andrew W.K. was, they sort of knew the image.

AS Right. And seeing this image everywhere implied importance—it made you think, What is it about this image that I need to confront?

It’s also interesting, looking at it now, to see the juxtaposition that you often see in your work. There was something really interesting about this heavy metal rocker in a basketball jersey. His nose is bleeding. He’s looking on like it’s a normal day, like nothing’s happening. It forces you into looking harder, looking deeper. Nowadays the divisions are a lot less noticeable—you can slip from being someone who plays guitar to being a skater to also enjoying basketball. Back then, you were a basketball guy or you were a rocker—identity was a lot more fixed. And in this image, you get an unfixing of identity that I think is also characteristic of the work that you’ve made through the years.

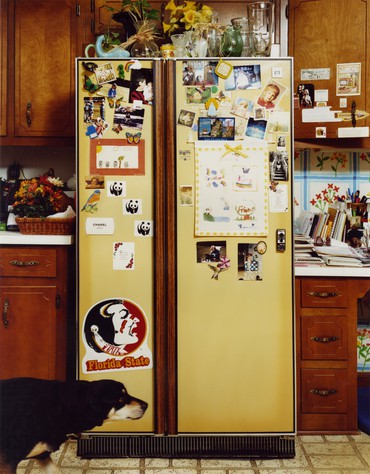

But you talked about collaboration earlier. How does that work for you? Some photographers are super open to feedback from subjects; others have an idea in mind. And another part of that question is the fact that you seemingly make no distinction between shooting someone like Telfar [Clemens] and shooting old fruit, or pigeons, or the American landscape, or the refrigerator in your parents’ home. There seems to be an approach that in some way ties all of these subjects together. So I was wondering about your thinking about subjects and objects, and their relationship to you as a photographer.

RE Well, I guess over time I’ve found that I’m more jujitsu than kung fu, to use a martial arts analogy. I like to have a thing to work with, an energy that’s coming at me so I can do something with it. Within a commercial operation there are different considerations, so it gives you boundaries to push on. And I suppose that works really well for me. I can ask, What do you want? And they say, Well, this is what we want. And then the artist part of me thinks, Okay, let me take it right to the edge of that or to the edge of what is acceptable, or How do I invert that?

Simultaneously, I’ve found that I have to start from somewhere. And so baseline intention is, What is my voice? I’m constantly asking that. Do I have a voice? And trying to get my voice through this heterogeneous thing: Can you hear me through these different types of photography?

AS Another thing that emerges in looking at your work is a sense of America, or Americanness. There is the body of work called American Spirit, for example, with images that are in some ways the trope of the American photographer taking on America—from William Eggleston to Richard Prince and the Marlboro Man, to Robert Frank, the list goes on. In your show Old Fruit, too, or your Rockaway book or the model photographs, it’s almost like America is another subject or another character. But there’s something about your images that messes with the conception of American beauty, with the idea that we’ve inherited this certain value system. It seems that you’re in some ways taking aim at these iconic Americana images that we live with and grew up with.

RE For some reason, I feel like I want to go to Paul Outerbridge now, and Man Ray. When I was in art school, I didn’t learn about Outerbridge. I learned about Man Ray and Alfred Stieglitz. Pictorialism was so passé, but that’s what I wanted to know about [laughter].

There is that Stieglitz picture of the gelded horse—the harnessed, castrated horse—that he called Spiritual America [1923]. And then back to the late twentieth century, Prince made a picture called Spiritual America [1983] that was a baby Brooke Shields behind a curtain, you know? So for me, American Spirit was a joke about Spiritual America in some ways, but it was also the name of the cigarettes that I smoke—so it’s kind of a mash-up of Marlboro Man meets Stieglitz. I guess it felt like the Stieglitz picture represents that idea of “I’m making the highest art statement with the medium”—it speaks to that schism between art and applied things. And these things seem particularly American because of the success of twentieth-century industrial Americanness—from the can of soup to the Model T, whatever it was, it needed photography to come along with it, to depict it, to tell you how to use it—lifestyle instructions or something [laughs].

Discovering Outerbridge was like opening up a world of Americana that I didn’t know, but I knew. When you look at his work, it’s as high modern as it gets, like his formal still life The Triumph of the Egg [1932]. But then there’s his ad image of a group of men sitting around drinking coffee—it looks like the most repressed white people having a coffee. For whatever reason, maybe knowing what it was like to grow up in that suburban world, I feel the dark and the light, the undercurrent, the sort of repressed or suppressed violence that’s in that picture. And then to find out that Outerbridge also made all these crazy pictures of fetish models, and he did sweet still lifes for the cover of Vanity Fair as well—it was like he was living five different lives. He was an American who wanted to be an artist but needed to make some money.

I have to start from somewhere. And so baseline intention is, What is my voice? I’m constantly asking that. Do I have a voice?

Roe Ethridge

AS Thinking about his work, there’s a softness to the way that he used light. It seems you go in the exact opposite direction—this idea of making images that are so filled with light that it produces something a bit more harsh. I was wondering if those formal aspects of his images informed your thinking.

RE I suppose it’s like everybody has their palette or something, but it was somewhat determined by the technology. For Outerbridge, a lot of his work predated color photography, so he was essentially inventing what later became the carbro print. He sort of invented making color images.

AS In some ways, the history of photography is the history of technological advancement, right? And in a part of your practice, even as you’re crossing genres, you’ve also decided to pick up things like the iPhone and test the limits of what that type of camera can do.

RE Well, you know, when I was in art school, I thought that I was smarter than everybody else, like young people tend to do. And I thought, Everybody’s doing these emotional, black-and-white pictures, but everything’s been done; there are no more new pictures to make. So I refused to use a 35 millimeter camera. I would shoot SX70 Polaroids. I was like, I’m not even a photographer, I’m an artist, you know?

AS Right [laughs].

RE At some point I decided to take a 4 × 5 class as an elective. I can remember shooting in a cemetery in Atlanta the first day and thinking, This is real; it’s hard. But it was so architectural in the way that it rendered things, in the way you had to slow down and really look. Because you’re looking at the ground glass, and it’s upside down and backwards, and so it becomes very still-life compositionally. Everything becomes that—architecture, people, the bowl of fruit. That really appealed to me. Shooting with a 35 millimeter felt like using a machine gun, whereas this was some other ancient kind of tool.

The result was fascinating, too, because the resolution was so high; it was like the thing depicted was more real than the thing in real life. For a long time that was fascinating to me. But at a certain point it started to get a little ridiculous—I was shooting hundreds of sheets of 4 × 5 film. That’s not what large format is supposed to be about.

AS Yeah, it takes a lot of dedication on everybody’s part—the artist’s part, the subject’s part. It takes a while to take those images.

RE Right. And at the same time, I was working on a soup-to-nuts commissioned project downtown, at Goldman Sachs headquarters, and I realized I couldn’t take the pictures that I wanted to take with the 4 × 5; it physically couldn’t be done. At that time, the Canon was just rolling out, so during the period when I was shooting that commission, between 2005 and 2011, I came around to the idea that “this is how you do it, and you sacrifice something but you also gain something.” Technically that appealed to me. There was also something about being a modern citizen and using the ubiquitous tool—if this was the common tool, well then I wanted to use it.

Later, in the studio, I started thinking of the scanner as the same kind of thing—it was like another camera. And pretty soon after that, it was like, Am I going to use this iPhone picture in this show? That’s crazy! [laughs] But it just made sense as it was another part of the ordinary technology of image making.

AS So, you’ve been doing this work with Telfar recently, including the special issue of Garage [no. 17], with the photographs of Telfar and Jeremy O. Harris. Those images are absolutely beautiful, and surreal. They also tie into this idea of America, because Telfar talks about how he wants to make an American brand and to make clothes for everybody. There is this democratic thinking around the construction of his clothing, but also in the cast of characters that he surrounds himself with, as you know.

Going back to this idea of collaboration, how did those images, which operated in a magazine context, but also in an art world context—how did you go about making them? Could you also talk about the relationships that develop in these projects, where you drop in and you make these relationships with communities and bring them a part of your world and your aesthetic?

RE I think that’s the great good fortune of being a photographer living in New York right now. I’m certain it wouldn’t happen if I wasn’t here. But it also has a lot to do with Babak [Radboy]—

AS Telfar’s creative director.

RE He’s the one who has facilitated these projects. With the project for System [no. 12], the idea was in some ways to have a kind of weird reversal of cultural appropriation—like my sort of white stock photography, but without any apparent irony. It’s Telfar’s entourage in Telfar’s streetwear with French rococo wigs on, on a sailboat, having a barbecue at the golf course . . . and we’re not going to say anything about it and we’re just going to go about our business, sailing, golfing, having a good time. It’s a party, but it’s not like you’re at the party; it’s the party depicted.

And because it was for System, which is very influential but at the same time sort of obscure, I knew that there was a fashion audience that was built into the story—the fashion insider who’s looking at System magazine. And bringing Telfar in in this way that’s silently in your face—it’s not screaming, but it’s in your face. The context was so rich, and the collaborative spirit could only have happened with New Yorkers—do you know what I mean? There was something magical with that story.

Sometimes I do editorial stuff and I know it’s just an editorial. With the System piece, I knew: there’s going to be something that goes up on the wall from this. It felt important before we shot it.

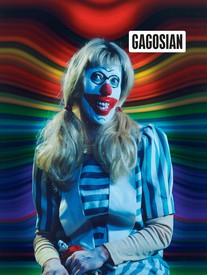

AS Your show at Gagosian, Old Fruit, looks at the last twenty years of your photographic and creative practice. These iconic moments from your career, what do they say about the photographer?

RE I guess for me, there was something about going back into that archive for this show. I’ve done a couple of survey shows, and this was a different thing. We knew we wanted the pigeons to be in there, and the moons to be in there, and then it almost became a 1999 to 2004 show, you know? And that refrigerator image—it’s never been shown in an exhibition other than a survey show—so here it felt like it got to have a little more volume. Seeing it again, in this moment—it’s so ancient. I mean, that kitchen was decorated in 1983 or something, and the photo is from 1999. So it feels like it’s speaking to olden times. I see myself there twenty years ago, even forty years ago—the pictures of me from when I’m an infant, on the refrigerator door.

So I guess in some ways the attempt was to make a poetic notation about what I’ve been doing, taking one image from this part, one image from this part—like if the refrigerator held all the secrets.

Artwork © Roe Ethridge; Roe Ethridge: Old Fruit, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, February 26–May 30, 2020