Lauren Mahony is a director in the publications department at Gagosian, where she has worked on exhibitions and publications devoted to Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Brice Marden, and David Reed, among artists, since 2012. She previously worked as a curatorial assistant in the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Rob McKeever

On May 4, 1959, Willem de Kooning opened an exhibition of new paintings at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. Six years after he had divided the art world with his controversial third series of Woman paintings, the 1959 show of large, abstracted landscapes was an unqualified triumph: well received by critics, it drew huge crowds and sold out within the first week. Just three weeks after the show closed, and as a direct result of its success, the artist purchased land in Springs, in East Hampton, where he had spent most summers throughout the decade. The East End of Long Island appealed to him because of its diffused light and quiet seaside atmosphere, and because it reminded him of his childhood in Holland.

Although de Kooning would begin to spend more and more time in Springs, it would take nearly four years for him finally to leave New York and take up permanent residence on that parcel of land, in a house and studio he personally designed. In the intervening years, between 1959 and 1963, as he thought retrospectively about his career, he would make some of his most magnificent and personal works, with the light of his future home at the forefront of his mind. Perhaps because of the wide range of smaller-scale works dividing his attention—his next solo Janis exhibition, in 1962, included “six types [of pictures], from five places”1 —and the relatively few large paintings completed, this period is sometimes overlooked or misinterpreted. However, it should be seen as a critical moment of rediscovery and refocusing of his powers, one that allowed him to pursue the kind of art that most pleased him, as new artistic movements, particularly Neo-Dadaism and Pop art, began to supplant Abstract Expressionism as the avant-garde styles of the day.

Over the course of these four years, de Kooning would make works that vary in scale, medium, and degree of abstraction, but all are the clear result of an artist newly confident in his creative voice. As he told David Sylvester in 1960, “I get freer. I feel I am getting more to myself in the sense of, I have all my forces. . . . I have this sort of feeling that I am all there now.”2 When the critic Thomas Hess, writing in 1968, offered general descriptions and dates for de Kooning’s multifaceted oeuvre, such as the oft-cited “abstract parkway landscapes,” “abstract pastoral landscapes,” and so on, he was quick to qualify this methodology: “de Kooning keeps as many possibilities going at the same time as he can, each feeding the other, each in a sense inhabiting the other. So a division of his work into types could result in the ultimate parody of art-historical periodicity in which there are as many periods as there are pictures.”3 This being so, in order to understand de Kooning’s practice, particularly during these years, one must examine series worked on simultaneously, to see how they “inhabit” each other. For the period of 1960–63, the large-scale “abstract pastoral landscape” paintings and the smaller works on paper that comprise his fourth Woman series, not often discussed together, were both represented in his next exhibition at Janis, in 1962, and have intriguing formal parallels. Looking at the two series side-by-side, the figural nature of the so-called landscapes becomes undeniable. As de Kooning told Hess in 1953, “the landscape is in the Woman, and there is Woman in the landscapes.”4

When de Kooning traveled, away from his primary studio in New York, he frequently borrowed or created makeshift studios so he could continue working. While in Rome for several months in the winter of 1959–60, he worked in the artist Afro’s studio. In the summer of 1961—with his daughter Lisa (then five years old) and her mother, Joan Ward, recently returned from the West Coast—he worked in a garage adjacent to the East Hampton house where they were staying, long before his new studio in Springs would be complete.

John Elderfield speaking on Willem de Kooning

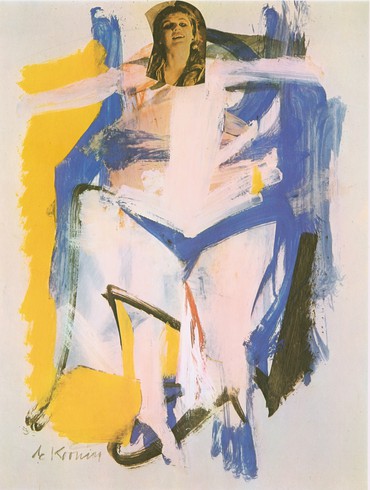

It was there that he embarked on a new series of Woman paintings on paper. Smaller in scale than his recent landscapes, due to his limited workspace, they are the first fully realized images of women—not disembodied fragments of anatomy—that he had made since the mid-1950s. Woman I Springs (1961) is composed with the same broad brushwork and palette as the pastoral paintings contemporary to it, with blue outlines loosely delineating pink flesh. Depicting the figure with arms extended and her right leg in two positions, de Kooning suggests a body in motion, perhaps swimming in Napeague Bay, the blue paint around her indicating water. He completed this figure by collaging onto the paper a photograph of a woman’s head, likely cut out from a magazine, to assert unequivocally that this is an image of a woman.

Willem de Kooning, Woman I Springs, 1961, oil on paper with collage, 29 ¾ × 23 inches (75.6 × 58.4 cm). Photo: © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

The other paintings in this series, of which Woman III Springs (1961) is a prime example, do not include collage elements, but they also clearly depict individual women’s bodies in full. The main indicators are the pink used for their flesh and their summarily described legs, feet, and toes. Nearly all of them are surrounded by areas of blue and yellow, suggesting the beach. The works in this series continue the theme of women exulting in idyllic landscapes, initiated in the early 1950s, which de Kooning would continue to develop throughout the ensuing decade, on a grander scale once he settled into his vast new studio.

The pastoral landscape paintings of 1960–63 differ in some important ways from the so-called “parkway landscapes” that comprised the 1959 Janis show. First, the brushmarks became looser and less likely to suggest an architectural space; in the words of Hess, “the forms became fewer, the surfaces bigger and less apt to be interrupted.”5 Second, de Kooning’s palette shifted to paler colors keyed to white—yellows, pinks, and blues—influenced by the light and waterfront landscapes of the East End.

Paintings from this group, including Door to the River (1960), Untitled (1961), and Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point (1963), although deeply inspired by the seaside environment, were in fact made in New York, in a new studio at 831 Broadway—by far the largest studio de Kooning had ever worked in, and with more natural light than his previous studios. In it he had “painting-walls on casters so they could be moved to catch the best light.”6 Door to the River, the earliest painting in the group, features some of the scaffolding of the earlier parkway paintings, with noticeably broad brushmarks and clearly differentiated zones of activity. By the following year, in paintings like Untitled, the brushmarks appear larger and less distinct because the areas of color have become more uniform, especially in the pale pink that dominates the composition. The overall effect of this more expansive use of pictorial space is to surround the viewer with an impression of the light and landscape.

These landscapes also differ from their predecessors in their overtly figural nature. The poet John Ashbery said that these paintings not only depict “topography,” but “woman looked at too closely to be legible as such.”7 In Untitled, for example, the pink form that occupies the center of the composition begins to resemble a reclining woman, the V-shaped brushmarks at left suggesting her raised knees, similar to those rendered in Woman III Springs. The oversized, simplified eye seen in profile—a motif dating back to de Kooning’s late-1940s abstractions—is present in the Woman painting, and hinted at in Untitled, in the yellow triangular shape at upper left. The way de Kooning ran colors together with his brush—bright blue cut with pale pink—was informed by his renewed interest in figural painting, particularly bodies submerged in water. When the pioneering gallerist Virginia Dwan purchased Untitled, in 1962, de Kooning told her she could call the painting Flesh if she preferred.8 In Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point, the pink paint in the lower center of the canvas outlines a truncated female form, her breast in the foreground and her thigh projecting away from the picture plane.

Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point and another painting, Pastorale, were the last major paintings de Kooning completed in New York in early 1963 before moving permanently to Springs. There, he would quickly embark on another series of Woman paintings—these painted on tall doors that were acquired but never used in the construction of his studio—that, in contrast with the pastoral landscapes that seamlessly combine close-up views of women with the landscape, are more overtly figural.9 As Hess summarizes the changes that occurred prior to the move to the East End, “De Kooning’s simplification of shape and format in the years 1957–1963 was the necessary discipline to arrive at his new colors. He could not have known that this was where he was going when he started out. . . . But he did finally arrive in the country and with the colors he needed to live there.”10

1Thomas Hess, Introduction, in Recent Paintings by Willem de Kooning (New York: Sidney Janis Gallery, 1962), n.p.

2De Kooning in “Content as a Glimpse,” interview with David Sylvester, BBC, recorded March 1960, broadcast December 1960; originally published in Location 1, no. 1 (Spring 1963); reprinted in Thomas Hess, Willem de Kooning (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1968), pp. 146–50; quote at p. 150.

3Hess, Willem de Kooning (1968), p. 26.

4De Kooning, quoted in ibid., p. 100.

5Hess, Willem de Kooning (1968), p. 102.

6Ibid., p. 101.

7John Ashbery, “Willem de Kooning: A Suite of New Lithographs Translates His Famous Brushstroke into Black and White,” Artnews Annual 37 (October 1971), p. 119; quoted in Richard Shiff, “Abstraction Not Abstraction,” in Willem de Kooning: A Centennial Exhibition (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2004), p. 13.

8Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, “Willem de Kooning: Painting in a New Light,” in Willem de Kooning, Untitled 1961 (New York: Christies, 2006), p. 32.

9The paintings of women on doors include Woman Sag Harbor (1964), in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC. Later in the decade, works such as Two Figures in a Landscape (1968), in the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, more fully integrated the two subjects.

10Hess, Willem de Kooning (1968), p. 103.

Artwork © 2020 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York