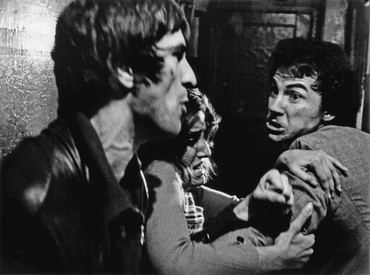

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Where have all the gangsters gone? It’s not enough to say they’re in the White House. The current American criminal at the top is doing a dismal job of acting like the old popular gangster, that glamorous yet deadly creature who cut men down with the agility of a ballerina (Jimmy Cagney) or swung with a brutality doubled by Catholic guilt (Harvey Keitel). Martin Scorsese’s recent film The Irishman tells us where all the gangsters have gone: once a hell-raising anticop icon of nonconformity, the gangster went to work, integrating himself into the business of workaday late-capitalist society. By now, such an answer isn’t particularly fresh. Crime dramas like The Godfather, Part II (1974) and Scorsese’s own Casino (1995) have already given similar glimpses of killers donning suits and forsaking “honor” in the name of bureaucracy and the dollar. So what distinguishes The Irishman, the culmination of America’s last bard of classical gangsterism?

The Irishman is the kiss-off to a breed of sick men and to a cruel genre. The antithesis of Goodfellas, which was all noise and nonstop action, The Irishman is built around a series of increasingly melancholic silences: the silence of daughters to fathers, the silence of a mundane morning breakfast in a Howard Johnson’s on the day you’re to kill your best friend, the silence of history when no one wants to remember it, the taxing spiritual trek of Scorsese’s Silence (2016), the silence of the living room in which viewers are asked to watch The Irishman. This depressing Final Gangster Epic is good at showing what it’s like to be forgotten in the digital age. It has a sleek look as relentless as The Conformist (1970), Bernardo Bertolucci’s film of a clockwork Italian “civilization” in political and moral freefall.

Simply put, the gangster has gone out of style because the job is no longer specialized: today, any idiot with a Twitter handle, a 401K job, and a trust fund can steal enough to become a symbol of infamy. With the consolidation of power by Silicon Valley tech, the gangster has become ordinary, nerdy, looking like Jesse Eisenberg in The Social Network—milquetoast on the surface but our greatest threat in the long run. This parallels what’s happening in movies today, as we forego the power of a theatrical space in order to see the film in the numb cocoons of our beds, with the film’s scope shrunk to the size of a plate and distractions all around. In making The Irishman with Netflix, Scorsese was recognizing that the only way to bring his vision to life was by dealing with a company set on returning viewers to the solipsistic couch, a departure from the communal, shared, submersive experience that has been the basis of moviegoing for more than a hundred years. And with The Irishman—which I consider less a gangster picture and more one of his intense psychological dramas, like Silence or New York, New York (1977) or The Age of Innocence (1993)—Scorsese makes a weird, stately epic (his Barry Lyndon, 1975), obviously designed for the big screen but consumed en masse on the home front. Here’s the curious thing: Scorsese’s not mourning the loss of gangsters or cinemas in fawning reverence for the good ol’ days, he’s not overcome with the frozen nostalgia that grips Quentin Tarantino in Once upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019), or Christopher Nolan in his painful Zola-like attempts to literalize each shiny helmet of each English boy of each battalion at Dunkirk. Rather, Scorsese accepts the new, outrageous state of the world, and brings to The Irishman, and to the people, all the memory and knowledge of history, moving art, and labor politics that can’t be accessed by a mere Google search.

The Irishman saps the glamour out of mobster killing, business, and betrayal. By contrast, Scorsese’s previous gangster pictures saw the ins and outs of these clandestine clubs with a glorifying eye, à la Howard Hawks’s Scarface (1932)—that is, they were as much voyeuristically swayed as repulsed by the carnage on display. Certain images of criminal macho swagger took on a disturbing pop-cultural beauty beyond any of the films’ critiques of such a life: messy bar fights set to the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman” (Mean Streets), bodies discovered in frozen meat vans to the tune of “Layla” (Goodfellas), psychotic Joe Pesci (Casino). One finds no such allure in The Irishman. The performances by Pesci, Robert De Niro, and Al Pacino are low-key, slowed by a softness that comes with age.

Interestingly enough, the two films that seem to have been jangling through Scorsese’s head are none of his own but rather Bertolucci’s The Conformist1 and especially Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties (1939), an era-capping testament to gangster pictures that confirmed the legend of Cagney. Walsh recontextualized Cagney’s career as a snappy hood; he had Cagney go through familiar motions but filtered them through an old-age grace, with stakes of mortality that ran deeper than the simple tommy-gun kills of earlier Cagney ventures.2 Along a similar vein, The Irishman is Goodfellas drained of blood, wiser and without its seductive jangle. Both The Roaring Twenties and The Irishman are nostalgia-adjacent tributes to an era that the filmmakers are glad to be rid of. The lingering after-odor that connects De Niro’s yes-man, Cagney’s once-big hood, and Jean-Louis Trintignant’s fascist coward in The Conformist is failure. Failure to get with the times. Failure to change. But whereas Cagney goes out with flair and panache (note the pirouette as he stumbles down a set of proto-Godfather steps), and Trintignant goes mad in Bertolucci’s baroque geometric playpen, the fate of De Niro’s meek, stuttering “house painter” Frank Sheeran stings harder because his fade-out is so unremarkable, visually and narratively. Isolated in an old-folks’ home, stuck in a wheelchair, his friends dead or shot (by his own hands), Frank slips into shadowy nothingness for The Irishman’s gruelingly paced final half-hour. His last act is to tell a priest to keep his door open, since his daughter Peggy (Anna Paquin, who conveys hatred and loss in pure stares, the way silent actors used to) might walk in at any second (even though she has damned his soul) and he needs to be awake for her.

The air around the male heavies is pathetic and dejected, infested with the same time-is-running-out quality of the late work of John Huston.3 In the same vein, The Irishman is very much the work of an artist unapologetic about entering his late period. From the opening, Goodfellas-evoking tracking shot through a retirement home, Scorsese announces that this, his Last Gangster Picture, will be a conscious retread of his passions and his past, sapped of youth but not of vigor. The echoes of Scorsese’s eclectic universe pile up. There’s a famous scene in Taxi Driver (1976) where Travis Bickle (De Niro), the Vietnam veteran hell-bent on “cleaning up” the majority-black parts of Manhattan, buys an array of guns from a slick salesman (Steven Prince); that scene reappears in The Irishman when Sheeran (again, De Niro) is preparing to gun down Crazy Joe Gallo.4 The difference is that by the time of The Irishman (more than forty years after Taxi Driver), De Niro’s character is his own salesman, no middleman needed. In this and other scenes, his very being is defined by a fated aloneness5 —and, as Robert Warshow wrote in his famous essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero” (1948), “No convention of the gangster film is more strongly established than this: it is dangerous to be alone.”6

For a generation, moviegoers have come to associate the poststudio gangster picture with Scorsese and his gaba-goon squad: Keitel, Ray Liotta, and especially De Niro and Pesci. Let us first consider where Pesci fits into this strange new world, seeing as it is his persona that goes through the most strikingly radical transformation in The Irishman. As the Mafia boss Russell Bufalino, who pulls the strings and gives his blessing for the assassination of Jimmy Hoffa, Pesci has captivated so many in part because he’s the anti-Hoffa, both in his role in the movie and in his character outside it, where he presents as a team player who detests the spotlight and could give a shit about prizes, Oscars, or the threat of an outsized Pacino outburst.7 The Irishman’s key existential line, “It is what it is,” is whispered by Pesci of all people, an actor who made his name portraying sadistic firecrackers subject to fits of rage that are still the stuff of drunken late-night impressions (“Funny, how?”). Now, shockingly aged, Pesci-as-Bufalino is a barely speaking sage, acting as the unofficial uncle of young Peggy, who does little to conceal how unimpressed she is with him. Pesci has become a steady, unconditionally loving wise man who prefers to sit in the corner and lurk unnoticed. As he chats with De Niro in a bowling alley, Pesci crooks his arms in the air against the nonexistent back of his low chair. From any other actor the gesture would seem awkward, a strained attempt at looking casual, but the relaxed Pesci makes it seem refreshingly ordinary. The Irishman hints that men like Pesci/Bufalino are fin de siècle leftovers not long for the brave new iWorld. Pesci maintains an economy of expression and a refusal of blustering presence that’s not only a rejection of his young dependence on sadistic mile-a-minute Cagneyisms, it’s also his response to changing times, in which those in the amnesiac present see a classical mode of living and find it too clean, too irrelevant, too old.

De Niro in The Irishman plays without a doubt the most unnervingly passive of all of Scorsese’s gangster leads. For the most part, his Frank Sheeran is a collection of blank and confused stares. He lets out shrugs at odd times when he talks, revealing his discomfort and bemusement at any situation in which he has to talk to anyone but Hoffa and Bufalino. His first lines are telling: “When I was young, I thought house painters painted houses. Heh-heh. What did I know.” We soon see that Frank doesn’t seem to know much of anything. He’s a frustrating drone who’s only good at dispatching civilian undesirables on demand—then muttering to himself, seconds before or after the deed, “What’s that about.” Scorsese glimpses inside a killer and finds empty space. Sheeplike and nervous, passion tamed and without a garrulous inner life, following orders on a nine-to-nine time clock, Frank Sheeran has more in common with newly graduated centennials than one might expect.

Of particular note is the voice, filled with stutters and cracks, that De Niro has developed for his character. A nervous babble creeps into Frank’s attempts to recall Cuba/union/Mafia dealings that are too complicated to remember and that no one alive cares about anymore. Here is a worker (an exsoldier who killed scores of Germans during World War II) who is scarily complacent, confident that the Gray Flannel Suit world in which he ekes out a humble mid-century living as a contract killer will never change. Like the meek fascist hitman of The Conformist, Frank takes good ol’ US business-as-usual as a permanent given—with tragic naiveté. He refuses to pay attention to the larger 1970s global realities of Vietnam, Richard Nixon, political assassinations, civil rights. All that matters is figuring out which of his friends will tail the wife of an enemy union man running for president of local-chapter XXX. De Niro’s Frank is rarely vindictive and lacks the ability to launch into male pyrotechnics, like previous Scorsese hotshots: his own Johnny Boy of Mean Streets (1973), Keitel in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), or De Niro himself again as the abusive sax-player Jimmy Doyle in the surprisingly mean-spirited and brutal “musical” New York, New York. This is Frank’s spiritual failure: unable to really feel anything, he is doomed to a life of both solitude and mediocrity.

Yet the question remains: why is the classical gangster dying now? It would seem that Scorsese is doing a double trick: he kills off the gangster he helped to create in order to point us in the direction of a world that’s about to change more vastly than we ever thought possible, new lines drawn in the sand, new allies and enemies to be aware of. Along the same lines as David Lynch’s 2017 reboot of Twin Peaks, The Irishman is defeatist but not defeated. In this it runs counter to a current trend that I find it fit to call the New Hollywood Pessimism.

By way of brief historical context: in “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” Warshow identified a sickening American optimism, of which, he argued, the popular movie gangster was but one of many consequences. “At a time when the normal condition of the citizen is a state of anxiety,” he wrote, “euphoria spreads over our culture like the broad smile of an idiot.” Euphoria, for Warshow, was the postwar state of mind in a popular culture that saw prosperity in every nook and cranny of a Levittown suburban home, a euphoria that had been building in the minds of American moviegoers, what with the scores of happy-go-lucky wartime films ranging from the asinine (Wilson, 1944) to the sublime (Vincente Minnelli’s touching, aching Meet Me in St. Louis, 1944). Against the backdrop of such films, so cheery on their Technicolor surfaces, the black-and-white gangster rocketed into the sky, riding on his own sadistic glee and the ease with which he could quickly be pinpointed as the only menace to an otherwise “healthy,” blessed republic. The wearily optimistic 1948 viewer could thus see gangsters shoot up hoods on the street, smash women’s faces with grapefruits—but all with the assurance that order would be restored, that Cagney or Robinson would get some narratively bland comeuppance. To Warshow, the singular gangster made morality in the modern age too easy to understand. The problem was not the system, these films argued; it was just Cody Jarrett (Cagney in White Heat of 1949), whose defeat called for nothing less than literal explosion in order to restore order and stall chaos. The American viewer’s naive confidence in a boom that was not felt by all, that did not last, was thus confirmed.

Bit by bit—a Manchurian Candidate and a Kennedy killing here, a Nashville and a Nixon impeachment there—Americans became disillusioned. They distanced themselves from art and the direct world around us through irony, nostalgia, computers, and a suspicion of new popular cultural trends (the idea of a thriving studio-funded cinema not of the Star Wars kind, what was called “multiculturalism”). On the whole, Americans became distrustful of far more than just politicians—they started to distrust most public sectors of US life, the newspapers and the media, and any belief that the person next door holds with a sickly bold conviction. Today we are no longer living with the blanket euphoria that so bored Warshow, but with something just as bad: morbidly obvious nihilism. The basic line: everything that’s worth seeing or saying has been seen or said, plus end times are here, so let’s just ride the bomb and, instead of taking active measures to enhance our perception and change the world, go underground and wait for all this to blow over.

American movies have been there to reflect the curdling. Something like Joker (2019)—in which Todd Phillips of the manically stupid Hangover movies rebrands himself as a renegade Jean-Luc Godard of gritty comic books (and gets away with it!)—is the latest culmination of Lobster/Deadpool cinema and of the New Hollywood Pessimism. Pop culture has become sanitized, corporate, and serious to a malignant and boring T. Phillips microwaves the original breakthroughs of a Scorsese8 in order to sell a pop vision that appeals to the blanket pessimism of now—yet still handsomely profiting him and his fellow filmmakers, who scowl and frown and guilt-trip their way to the bank.9 As Warshow saw the gangster in his time, so do I see a cardboard bundle of mannerisms like Joker’s Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), whose empty anarchist glee only exists to confirm the viewer’s fear of the truly original, the truly wild and reckless and weird. By being against everything, these new spate of films are for nothing.

What we need now is a radical uplift, a refusal to be wooed by the same basic Lars von Trier–isms or Yorgos Lanthimos cruelties. Perhaps some answers lie in the aesthetics of late films—works by directors in their twilight years who were around to see the once mighty studios, bastions of pop dreams, crumble before their eyes.10 In the Denmark of 1964, an auteur such as Carl Theodor Dreyer could use his own conviction to make a final film like Gertrud, in which he has his lead declare, with a frightening lack of compromise, “When I’m near the grave and look back on my life, I’ll say to myself: I suffered much and made many mistakes, but I have loved.” To give love back to an unloving world makes Gertrud the only revolutionary of her time; undoubtedly, her route will end in pain, tragedy, jeers of hate, and promises of obscurity. Yet Gertrud accepts this, as does Dreyer, as do we. Gertrud ends with a closed door, but the dominant mood is one of surging, manic hope—what else have we left?

Now, in 2019, an auteur like Scorsese ends his late film with the least-inviting open door in all of cinema, the atmosphere heavy with defeat: daughter Peggy will never come, no one will mourn the loss of “just another” mob guy—what else have we left? The dead don’t die (Jim Jarmusch), the Irishman fades into the still of the night (Scorsese), and, in a silly fantasy, the slaughtered princess is saved and invites her hero into her Cielo Drive castle, while we either leave brutally aware of Sharon Tate’s real-life fate or, if we’re under thirty and don’t know anything about the 1960s, remain blissfully ignorant of history (Tarantino). All of these late visions put the power of cinema to its highest possible uses, but they land with a depressed thunk. They serve to confirm the viewer’s exhaustion. They are dead points. To varying degrees, they all flirt with the fashionable allure of New Hollywood Pessimism.

By contrast, last year saw late films by auteurs such as Agnès Varda (Varda by Agnès), Pedro Almodóvar (Pain and Glory), and Terrence Malick (A Hidden Life) that go somewhere light, nonearthly—angelic, even. Malick, for example, guides our vision toward daily details that we ignore: donkey pelts, pulsing greens that turn the world into transcendent garden scenes for three hours, the spells of flood and drought in an Austrian village whose people don’t understand where they fit in the larger landscape of history-morality-politics. By burrowing so fastidiously into the mundane, Malick transports us out of our time and, like Dreyer, makes us aware of our mortality and need for love, companionship, movement—and all without a smack of defeat. Like Dreyer, he cannot compromise—which means he’s been branded as a naïf and a fool. And so he is. Just as one tense settles (the ethereal/eternal past-future tense of Malick), another tense takes its place (Scorsese’s brute, necessary, hard-edged present tense). From whose and which tense will we choose to speak now?

More than ever, as the dreamers of musicals and the second-wave gangsters die away, we study the legacy they left behind—and we must choose to conjure up their spirit in new forms of expression, not to trot out the old dependable classics, unchanged, unchallenged, and declare humanity a lost cause.

1The critic and filmmaker Neil Bahadur was, to my knowledge, the first to make this crucial connection, in his Letterboxd film review of November 8, 2019, online at https://letterboxd.com/neilbahadur/film/the-irishman-2019/3/ (accessed March 20, 2020).

2Those earlier Jimmy Cagney ventures include William Wellman’s Public Enemy (1931), Roy Del Ruth’s Taxi (1932), Archie Mayo’s Mayor of Hell (1932), and Michael Curtiz’s Angels with Dirty Faces (1938).

3I am thinking of Fat City (1972) and The Dead (1987).

4Bob Dylan later wrote a song in tribute to Crazy Joe, “Joey,” for his 1976 album Desire, an album he later promoted with his now-legendary Rolling Thunder Revue tour—and which, in 2019 (the same year as The Irishman), Martin Scorsese would document in Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, another Netflix exclusive.

5It’s necessary to point to the large influence of John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), and specifically of its central character, the doomed loner/wanderer Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), on Scorsese’s imagination of his male leads.

6Robert Warshow, “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” 1948, in The Immediate Experience: Movies, Comics, Theatre, and Other Aspects of Popular Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), pp. 132–33.

7Joe Pesci may hold the record for short Oscar speeches. When accepting his Best Supporting Actor Academy Award for Goodfellas, in 1991, he simply said, “It was my privilege. Thank you.”

8From Who’s That Knocking at My Door? (1967) through After Hours (1985), Scorsese made consistent breakthroughs in the history of US cinema in his unsparing, realistic depictions and critiques of masculinity, from its brutality (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in 1974, New York, New York in 1977) to its farcicality (The King of Comedy in 1982, After Hours in 1985). Here was an artist unafraid to show the extent of the violence inflected by the male loner. Scorsese learned all the best lessons from gangster films to create remarkably original studies of American masculinity and its sputtering failures.

9After seeing Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here (2018), either in theaters or on Amazon Prime, one might consider it the film for which Joaquin Phoenix might more aptly have won his Joker Oscar. It’s a performance of the same Joker intensity and woven from similar material: the descent of a mentally unstable male loner into an expressionistic pit of New York madness, inspired by Taxi Driver. But I find Phoenix better employed in Ramsay’s film—it’s gutsier and of a piece with Ramsay’s last film, We Need to Talk about Kevin (2011), which might be bluntly characterized as an existentialist hate letter to American masculinity in crisis.

10Key to the late film’s charm is the prizing of small, scruffy bits of action over the tightness of a narrative in which each action exists along a clean arc. At the expense of narrative propulsion, the late auteur’s focus is on process, planting the camera on actors who like each other and recording the ensemble harmony. This relaxed state results in films that are odes to mere being, a love of people that is baked into the drawl of such landmarks as Howard Hawks’s Hatari! (1962; a study of horny white zebra-chasers in Africa that is stretched to an absurd 160 minutes), the DIY home-movie comfort of Agnès Varda’s final films where each theatrical audience feels like part of a family, and even the buddy-buddy drudgery on display in The Irishman. Scorsese directs his best friends, who happen to be De Niro and Pesci and the like, to show the effort it takes to maintain a nonbloody front. For most of the film’s 200-plus minutes, actual business and killing are kept offscreen. When someone does get whacked, it has the quality of a telegram dispatch. Deaths are perfunctory facts, not a big deal, and the way blood pours out of an eye socket becomes less interesting to the late auteur than the brownstones nearby, lit in moonglow like the stoops where lovers meet in songs by the Platters.