Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

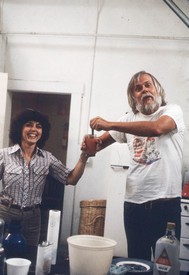

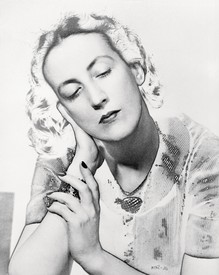

Niki de Saint Phalle, the jubilant, mystical sculptor who may be best known for her Tarot Garden in Tuscany, was due to have a retrospective at MoMA PS1, Queens, this spring. Whether I’ll ever see the show is at the time of this writing unknown, given museum closures resulting from the pandemic, but looking with longing through an online preview of its contents, I was reminded of Saint Phalle’s legendary 1966 exhibition at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Entitled She—The Cathedral, the show—co-conceived by Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, Per Olof Ultvedt, and the museum’s visionary director, Pontus Hultén—was a trailblazing redefinition of what a museum exhibition could be; it was humorous, multimedia, erotic, immersive, and built collaboratively for popular enjoyment. It was a sensation in every sense of the word. Saint Phalle had created for it one of her iconic Nanas at a momentous scale, the reclining figure serving as the architecture for the other works included in the show. Attendees had to enter through the Nana’s womb, whereupon they were greeted with a milk bar, screenings of an early Greta Garbo film, an aquarium, ad hoc artworks, and even a slide for the children.1 It was a feat that could only have been imagined through the collaborative minds of artists, and only staged by someone as daring and devoted to them as Pontus Hultén. In fact, She—The Cathedral is but one star in a constellation of experiments conducted by Hultén over the course of his long career. Over four decades and in multiple cities, and whether as curator, museum director, educator, collector, or patron of artists, Hultén worked with a creative, populist, anarchistic spirit rarely seen before or after.

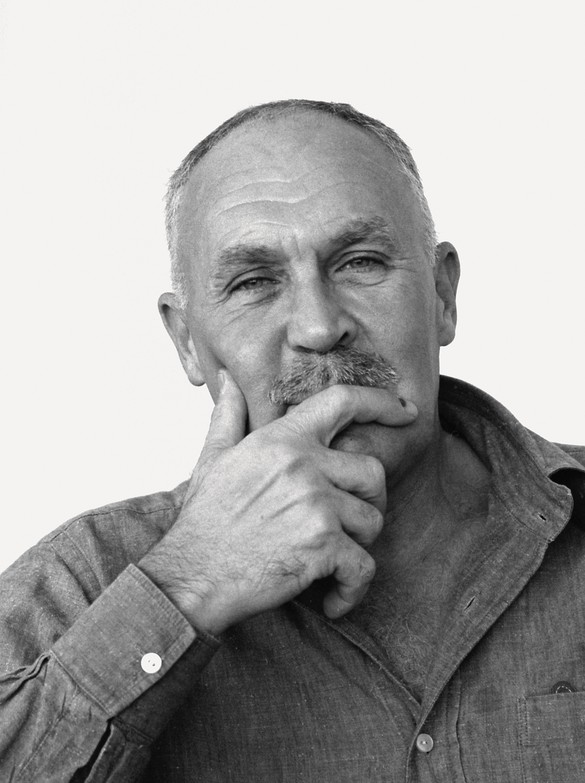

Saint Phalle, like many others in Hultén’s orbit, greatly admired the Swede: “Pontus works in the same way as an artist does—mainly on instinct.”2 That instinct was formed in his youth, first as a student at the University of Stockholm, where he studied art history and wrote a graduate thesis on Spinoza and Vermeer, then developing strongly during the 1950s as he traveled between Stockholm and Paris. Precocious and with a potent desire to know working artists, by 1955 he was working on such exhibitions as the first exhibition of kinetic art (ever) at Galerie Denise René, Paris.3 Planned in concert with René, Tinguely, and the painter Robert Breer, Le Mouvement included work by Alexander Calder and Marcel Duchamp. Not a bad start for one barely cresting thirty.

From there, Hultén took charge of the nascent Moderna Museet, working on the plans that would separate it from its original parent institution, Stockholm’s National Museum, and organizing its first exhibition—nothing less than a comprehensive presentation of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. In 1959, the year after the Moderna Museet opened, he became its director. During his tenure there he used his endless curiosity, his friendships with artists, and the changing face of the art audience to redefine not just the role of a museum director, and the ways a museum might engage the public, but what the very goals of a museum might be.

The museum must be opened to disciplines once excluded, and to the largest possible public, and this right away.

Pontus Hultén

As Calvin Tomkins argued in his 1978 profile of Hultén in the New Yorker, the democratic notion of a museum that we now take for granted was not always in place—these institutions were elitist, static, and conventional right up until the mid-twentieth century.4 It was through the work of directors like Hultén, and his mentor Willem Sandberg at the Stedelijk, Amsterdam, that living artists and a broad public were brought in. Dynamic programming came to be seen as a necessary function of the museum, and the idea of what constituted visual culture was vastly broadened. No longer would the museum be a rarefied house; for Hultén, it had to meet the needs of a new “anonymous public, curious, much larger, more varied, and, in a way, disoriented, which has replaced or bypassed the literate and curious traveller of the last century.”5

Hultén did this at the Moderna Museet with solo exhibitions of, among others, Paul Klee (1961), Jackson Pollock (1963), Barbara Hepworth (1964), and Francis Bacon (1965); landmark group exhibitions such as 4 Americans: Jasper Johns, Alfred Leslie, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Stankiewicz (1962) and Poetry Must Be Made by All! Transform the World! (1969); and with prescient risk-taking, including Andy Warhol’s first solo museum exhibition, in 1968.6 He did this as the curator of the historic 1968 exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He did this as the founding director of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, for which he left the Moderna Museet in 1973. He did this as the founding director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, leaving a deep impression during his time there despite exiting before the museum’s much delayed opening. He did this as the founding director of the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, and as one of the founders of the Institut des hautes études en arts plastiques, that intimate postgraduate art school in Paris.

Hultén’s time at the Pompidou may end up what he’s most remembered for. When the building opened, after a prolonged construction process during which the project endured vicious criticism, Hultén brought his desacralizing impulse to the space and staged a number of beloved exhibitions, beginning with a Duchamp retrospective, then moving on to a series of encyclopedic shows that traced the role of Paris in the development of twentieth-century art and visual culture. As he told Tomkins, “The museum must be opened to disciplines once excluded, and to the largest possible public, and this right away.”7

Hultén’s intuition and perception in all of his roles strikes me as tied to his lifelong enthusiasm for sailing. It was the activity with which he most often filled his holidays. Honed by his enduring passion for the hobby, Hultén knew the power of following currents, working with the changing winds, and keeping an eye on the ever changing horizon.

1See Daniel Birnbaum, “Passages: Pontus Hultén,” Artforum 45, no. 6 (February 2007). Available online at www.artforum.com/print/200702/pontus-hulten-12381 (accessed April 2, 2020).

2Niki de Saint Phalle, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “A Good Monster,” New Yorker, January 16, 1978. Available online at www.newyorker.com/magazine/1978/01/16/a-good-monster (accessed April 2, 2020).

3See Tomkins, “A Good Monster.”

4Ibid.

5Pontus Hultén, quoted in ibid.

6See Anna Tellgren, ed., Pontus Hultén and Moderna Museet. The Formative Years (Stockholm: Moderna Museet; London: Koenig Books, 2017), pp. 183–85.

7Hultén, quoted in Tomkins, “A Good Monster.”