John Elderfield is chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

Ambroise Vollard was not only one of the most important French art dealers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—some would say the most important—he was also an extremely gifted writer who published biographies of Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, and Auguste Renoir: promotional vehicles for his artists, to be sure, but great reading nonetheless, full of wonderful firsthand anecdotes. Among the pleasures of his book on Degas are the half-dozen nicely rambling pages recording the artist’s thoughts on the subject of paintings being altered after their completion by those who had not made them.

Degas was testy about his dislikes, and began by fulminating about a conservator wax-lining a painting: “giving it an ironing,” as he described it. Then he got to what was really on his mind: people cutting off from paintings a part they didn’t like. Someone he knew had said of the painting of a nude woman: “A good many society ladies come to my house, and I thought the lower part of the torso was not quite proper, so I cut it off.” Degas: “To think that an imbecile like that hasn’t been caught and locked up.” More alarmingly personal, Degas had painted a double portrait of his friend Édouard Manet and his wife in exchange for a still life of fruit. Visiting them, he “had a fearful shock”: Manet had “thought that the figure of Madame Manet detracted from the general effect,” and had cut it off. When Degas got home, he returned the still life with a stiff note: “Sir, I am sending back your Plums.” Then came the most interesting story. Vollard writes:

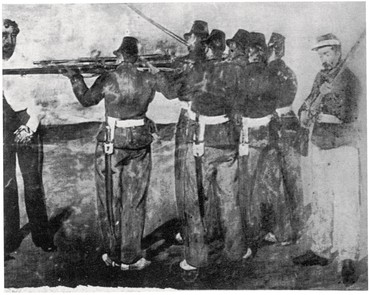

Sometime later I happened to meet Degas accompanied by a porter wheeling one of Manet’s pictures on a cart. It was one of the figures from the subject picture entitled, The Execution of Maximilian, and showed a sergeant loading his gun for the coup de grâce . . . [Then Degas shouted] “It’s an outrage! Think of anyone’s daring to cut up a picture like that. Some member of Manet’s family did it. All I can say, is never marry.”

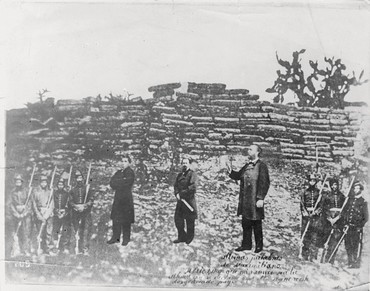

I remember admiring this painting of the upper half of a soldier when I first visited the National Gallery in London as a teenager. The label said that it was a fragment of a large, damaged painting of the execution of the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico, on June 19, 1867; I hadn’t heard of this incident, the history then taught in British schools being almost exclusively British history. And the label had nothing to say about how the fragment got to the National Gallery. Little did I know, of course, that I would eventually learn a lot about both of these things while preparing an exhibition of Manet’s paintings on this subject—for there were more than this one—that opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art late in 2006. Among the works shown there were photographs related to Maximilian’s execution that Manet would have seen. In an extraordinary irony, while the exhibition was on view, images of the execution of Saddam Hussein in Iraq were beamed around the world.

T. S. Eliot famously wrote that the art of the past is altered by that of the present, as much as that of the present is directed by the past. Looking back at Manet’s enterprise now, in a period of the production of far more art with a political message than a decade ago, does alter it. I will say something about that in the companion essay to this one to appear in the next issue of this magazine. Now, I will be arguing that the cutting up of this painting, deplored by Degas, now contributes to its delivery of its message. But let us first learn how the fragment showing the soldier got into the collection of the National Gallery in London.

This is what happened: the painting was a fragment of, in fact, the second of Manet’s Execution of Maximilian paintings, abandoned by the artist in 1868—of this, more in a moment—and left rolled up at his wife’s home, where it languished in storage. Probably before Manet’s death, in 1883, the left side of the canvas was cut away, by Manet or someone unknown, perhaps because it was damaged, thereby removing the images of Maximilian and one of the two generals executed with him. That was when the only contemporaneous photograph we have of it was taken. “Some member of Manet’s family”—in fact Léon Leenhoff, who has been described both as Manet’s stepson and as his half-brother; his paternity has never been revealed—subsequently discarded and burned the by-then, he claimed, seriously damaged lower sections on either side of the composition, and cut up the remainder into four pieces.

Then, in Degas’s words, “the sergeant loading his rifle . . . was hawked about and eventually sold for 500 francs to [the art dealer Alphonse] Portier who let me have it.” (This was the delivery Vollard saw on the cart.) Degas then set about searching for the other pieces that remained of the picture: one large piece, depicting the remainder of the firing squad of soldiers, and two smaller ones, showing the upper part of the second general. He eventually found them, and now with all four, Vollard reported, “proceeded to glue them onto a canvas prepared for the purpose, leaving necessary space for the missing parts in case they should ever be recovered.”

None others were recovered; and this was how the painting remained until Degas’s death, in 1917. The following year, the London National Gallery purchased it in the sale of Degas’s private collection—and, extraordinary though it now seems, proceeded to unglue the four pieces from the canvas on which Degas had so lovingly recomposed them. And so matters remained until another painter intervened. It is the National Gallery’s rule to itself that an artist should occupy a term position as one of its trustees; and when the painter Howard Hodgkin was appointed to that role, in 1978, he campaigned to have the painting returned to how Degas had left it, and eventually succeeded. The composition was first exhibited in that form in 1992. So, three artists—Degas and Hodgkin in addition to Manet—are responsible for the painting that now hangs as it is in London; as well as, of course, Léon Leenhoff.

What may be said in defense of what the National Gallery did?

First: there is no reason why, in principle, Manet would have objected to the exhibition of a figure removed from a composition with which he was dissatisfied. Leaving aside what he did to Degas’s double portrait of the Manets, when one of his own compositions, showing a death in a bullfight, was actually on the walls of the 1864 Salon, Manet “boldly took out a pocket knife and cut out the figure of the dead toreador,” a friend reported. And he made an independent painting of it.

Second: if Manet was a divider, Degas was a combiner. In his later years he enjoyed making paintings from pasted-together pieces of paper. The work that the National Gallery acquired could be thought a joint production of Manet, the divider, and Degas, the combiner.

And third: while the jigsaw that Degas assembled from the pieces of Manet’s painting would have fitted very comfortably into, say, the recent ecumenical exhibition of “unfinished” works of art at the Met Breuer, New York, it would not have done so on the walls of any major museum in 1918. Tastes have changed enormously since then, when the first modern collages had appeared only six years earlier. Now that collage techniques have persisted for almost seven decades—amazingly, longer than the entire period from Romanticism to Cubism—the current appearance of Manet’s painting speaks to us anachronistically as an example of the art of assemblage.

I said that the painting now in London was the second that Manet had painted on this subject. The first, now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, would also qualify for an exhibition of “unfinished” works. It appears to have been begun within days of news reaching Paris, on July 1, 1867, of Maximilian’s execution in Querétaro, north of Mexico City—quick at that time for a distant event that had taken place less than two weeks before. It was begun, therefore, before engravings and photographs that pretended to show episodes or objects documenting the event started to appear, in August of that year; and it is generally agreed that when Manet eventually saw such images he abandoned this first painting, which would not be exhibited until 1905. As it stands, its unfinish in fact speaks of the uncertainty of the story it purports to tell, and of how Manet changed his mind about what to represent when he made the London painting.

In shaping the Boston composition, Manet borrowed freely from Goya’s Third of May, 1808, a painting of 1814 in the Prado that depicts the execution of Spanish nationalists by invading French soldiers under the orders of Napoleon—the uncle of Napoleon III, the monarch of France in Manet’s time. Manet was imagining a situation that was, at face value, almost opposite to Goya’s subject: Mexican nationalists executing the representative of a French invasion. And he dressed his execution squad in flared pants and sombreros, which conformed to popular notions of what ordinary Mexican soldiers then looked like. Yet the borrowing from Goya suggests that he was beginning to implicate France.

In the London painting that followed, the implication was made explicit. Manet learned from a report of August 11, 1867, in the newspaper Le Figaro, that the uniform of the Mexican soldiers resembled the French uniform, and probably soon thereafter he saw photographs of the firing squad. He then brought into his studio a squad of French infantry to pose, and also painted the face of the sergeant loading his rifle to resemble Napoleon III. This was sheer provocation on Manet’s part, and while his painting had been announced for exhibition in the official Salon due to open in May 1868, there was no way that he could have received permission to show it. A photography dealer was jailed simply for being in possession of some of the photographs, by then in clandestine circulation. The painting therefore languished in Manet’s studio—what happened to it we already know—and Manet eventually began a third and final large painting, which is now in the Kunsthalle Mannheim.

I will defer to the second chapter of this story the changes in Manet’s imagining of this subject in that third painting, the extent to which they were influenced by incoming reports about what had actually happened in Querétaro, and how this relates to issues of political and polemical art and its censorship. To conclude now, I want to return to why I think the collage that Manet’s second painting became is such a compelling work.

We are to imagine the artist making this composition poring over a succession of newspaper stories of a distant, horrifying event, hoping for clarification and definitive truth, as we do now with such events, and either not finding it or disbelieving it, as we do now. We are also to imagine Manet piecing together fragments of news, knowing that they did not realistically or completely describe what had happened but offered, rather, the means of an imaginative act of rediscovery of something that was quickly receding into the past. It is purely accidental, of course, that the London canvas conveys something of this in its collagelike format, the parts not composing a complete picture and not quite matching up with each other. Still, its incomplete status as a painting gives it particular power as an incomplete remembrance. And knowing that Manet drew on composite images of the execution, images themselves made by collaging together photographs of the victims and the firing squad, reinforces our awareness of the process of assembly that shaped its imagery.

In the sky at the center of the London painting can be seen a diagonal motif, apparently a sword, that appears in neither of the other two compositions. It is especially puzzling because we cannot see the soldier holding it, Manet having hidden him behind the line of the soldiers who are firing their muskets. Late-nineteenth-century viewers would have known that it was customary in executions by firing squad that the command to fire be signaled by an officer either abruptly raising a sword or slowing raising and then abruptly lowering it. Now that that meaning has faded, the motif has become akin to what Roland Barthes famously called a “punctum,” something that catches our gaze without disclosing why it is there, even what it is, as opposed to the “studium,” the manifest meaning of a composition; therefore, inviting of subjective interpretation. I don’t think many people will associate the sword, this cutting device, with what happened to this painting, but it is there to wonder at in the sky; and perhaps some people will. What is unquestionably strange is that in 1861 Manet had painted a charming portrait, Boy with a Sword, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was in his possession when he put the sword in this Maximilian composition—perhaps even made him think of doing so. The boy portrayed in that canvas holding the sword was the young Léon Leenhoff, who would eventually cut up the extraordinary painting that Degas then saved.

Whether or not we know this, what remains unexplained is what precisely is happening in this cut-up painting. The muskets are firing, but one of the two generals who survived the cutting also seems to be surviving the execution; so presumably does the missing person—Maximilian?—whose hand he is holding. But why are there two left hands? And why is the general so unrealistically tall? And why is the soldier with a rifle so disengaged from the action as to seem almost to invite being cut off? In our age of assemblage, such narrative anomalies, far from further damaging the damaged painting, come across as entirely consonant with its now collaged format, the two forms of disjunction together fueling the excitement of unresolved recognition of what happened at Querétaro on June 19, 1867. But then, Manet himself did not know that when he made this painting; and when he did, he made yet another one.

Bibliographical Note

The information presented here is drawn from my Manet and the Execution of Maximilian (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), supplemented by my “Soldiers of Misfortune,” The Guardian, January 6, 2007, from which I have taken a few sentences. I also refer to Ambroise Vollard, Degas: An Intimate Portrait, translated by Randolph T. Weaver (New York: Greenberg, 1927); T. S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” 1917, in his Selected Essays, 1917–1932 (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1932), and widely anthologized; and Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1980, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).