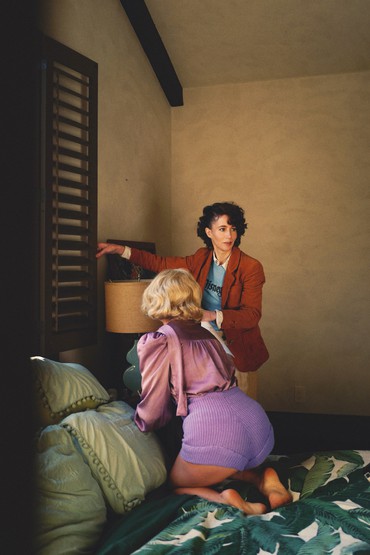

Miranda July, Nichols Canyon Road, 2020

Lavender: some words about a film about a painting

by Miranda July

The deal with surviving a pandemic is: you live a small life. You mostly stay inside. When you go out you go to the same places, safe places you know well. You see very few people, always the same people. Sometimes you forget why you are doing this—are you depressed? Is that why? Did the whole world become depressed at once? No. It’s to not get breathed on. It’s all to avoid the breaths of other people. And thus stay well, keep living and breathing, easily. With all this in mind, you can understand why driving on a new street in an unfamiliar part of town seemed a little reckless. I made a plan to visit Nichols Canyon Road on a particular day, as if it were very far away and I had to schedule my life around this trip.

And then all of a sudden, on the way home from an errand, I decided to just go. I exited the freeway abruptly at Hollywood Blvd.—it was like deciding at the last minute to go with your lover instead of seeing them off. I mean, not at all, it wasn’t at all like this, unless, as I said, you were living a very restricted life. The road was only fifteen or twenty minutes away from my house. There were hundreds of roads that were only fifteen or twenty minutes away, all radiating in a halo around me; I never drove on any of them anymore.

The black line at the bottom of Hockney’s painting is Hollywood Blvd., it’s the last bit of the known world; when you cross it to Nichols Canyon Road you’re crossing over into something wild. It’s really like this, for everyone, not just Hockney. Nichols begins in cold darkness, the trees are shrouding the road and because we are all just simple animals this makes us feel uncertain, doubtful, even a little sad. Transitions are hard, this one’s no different. I wondered if I even should have taken this job; how do you make a film about a painting? I was looking left and right for yellow and purple and orange and none of these colors were around. It wasn’t a circus, just the ordinary palette of life—some green but mostly gray and brown and white. But I was climbing, without noticing I was getting higher.

When I least expected it, the landscape broke open. The canyon unfurled and the sun came pouring in. I was suddenly high above the world and I wanted to laugh or yell. We were going to be ok! Life was still glorious! And I was twisting, this way and that, in and out of dappled, flirtatious sunlight and the elevation made my stomach lift like it does when your crush calls. The painting was on my phone, I stole a quick glance at it, wondering if I could find any of his landmarks, and half-expected to see the dot of my car moving up the brown squiggle as I drove, like on Google Maps. This was funny and life was funny, how it wound in and out of darkness and light—the darkness making the light ecstatic.

The colors were inside of course. In me, and exploding out of him, after living so long in England. In 1980 Los Angeles must have seemed glamorous and gay and sexy and free and the light was generous, warm, orange as he drove the squiggle back and forth to his studio. He was designing the sets and costumes for Parade, a ballet, and I was glad to find his red-striped Parade curtain repeated in the red roof of the central house in the painting. This reassured me that he does what I do (what any artist does): lets life come in. I wasn’t designing sets for a ballet but I was talking to my friend Angela a lot. She’d had a mastectomy to survive breast cancer and her silicone implants had rotated in a weird way from dancing too hard. So she decided to get them taken out but in the meantime she was trying to safely date online.

“I just want to make use of these breasts before they go,” she said. The woman she’d matched with wasn’t really taking full advantage of them. We shot the film on a Sunday, the next day Angela had a four-hour surgery and came out flat-chested. I sent her flowers and she sent me a picture of them, peonies. I sent back frame grabs of herself from the day before, careful to only send the curves she still had. But we’d recorded all of them; I’ll forever be swerving in a red convertible, left, right, left.

What you paint with is a moment in a time. A specific, fleeting mood when the world felt this way. And then, through no system we understand, that moment can be revisited by anyone, forevermore. But they will see it through their life—i.e., David’s 1980 seen through Miranda’s 2020. And because I’m a filmmaker, it’s not just my 2020, it’s Angela’s and the cinematographer’s, Natasha’s, who is from Argentina and can’t go home for the holidays because of covid, and the camera operator’s, Matias’s, and the focus puller’s, Hector’s… and the composer’s, and the sound designer’s, etc., etc., all these 2020s. Before we shot another take I would sometimes pull a color copy of the painting out of my purse and hold it in front of Natasha and Matias and Hector, who were all in the car with me.

“We must keep this in mind,” I’d say. “Some of these trees from 1980 are still here, let’s look for them,” and we’d all lean into the painting for a quiet moment. Jenny, the costume designer, kept the painting in one hand and with the other hand she picked through mountains of clothes looking for the exact lavender, orange, red hues. Her dog was sick in the animal hospital, so she was glad for the distraction. We decided against the more on-the-nose Hockney rugby stripes for under my blazer; I chose a light blue sweatshirt and white collared shirt, it just felt right. Later that day Jenny sent a photo of Hockney in a light blue sweatshirt with a white collar and I stared at it, wondering what he was doing right now, the night before the shoot, and what would I be doing forty years from now, when I am in my eighties.

On that first drive up Nichols Canyon Road I eventually stopped at the house where we would shoot Angela’s undressing; a wonderfully efficient location, geographically-speaking. Brigitte, the homeowner, was honored to loan her house for an homage to the painting. It was, after all, a painting of her street.

“Of course we all know it well,” she said of herself and her neighbors. “And we’re so glad he painted our canyon. Laurel Canyon is in all the movies, but ours is much more beautiful.” There are some undeniably special places on Earth where time collapses; you are lifted up out of your small world, your surgery, your sick dog, your pandemic, and for one winding drive all these aches are just blues and greens that make the reds and yellows pop. And the lavender, we all know, is love.

Short film and text © Miranda July

Horizontal-for-the-call: Angela Trimbur; Eyes-on-the-road: Miranda July

Producers: Elizabeth Litvitskiy and Melina Hayum; director of photography: Natasha Braier; editor: Aaron Beckum

Composer: Emile Mosseri; sound designer: Kent Sparling; sound assistance: Bjørn Schroeder

Camera operator: Matias S. Mesa; AC: Hector Rodriguez; location sound mixer: Oscar Grau Martin

Costume designer: Jenny Tsiakals; hair: Nikki Providence; makeup: Natasha Severino

DIT/colorist: Gianennio Salucci; assistant/BTS photography: Niki Byrne; PA: Madeleine Woolner

Thank you: Location: Brigitte Green; Car: Leandra Camilien; Sam Lisenco; Josh Bramer; EVB