Raymond Foye is a contributing editor to the Brooklyn Rail. His most recent publication is Harry Smith: The Naropa Lectures 1989–1991 (2023). Photo: Amy Grantham

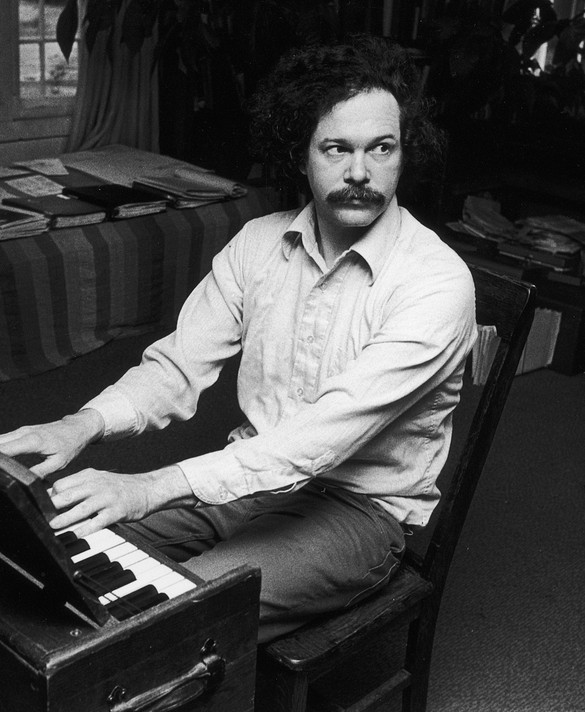

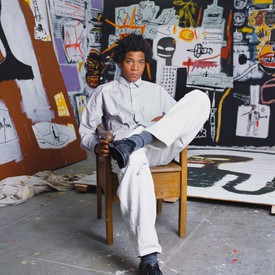

Poet and writer, bookstore owner and publisher, peace activist and environmentalist, and founding member of the musical group The Fugs, Edward Sanders turned eighty-one on the day I spoke with him in August of 2020. Sanders is one of the last great figures of the American counterculture, and from his home in Woodstock he remains as vital and productive as ever.

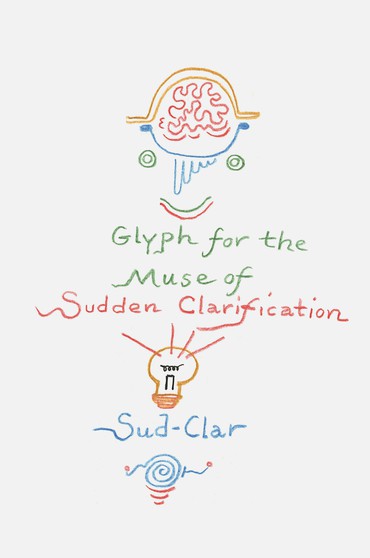

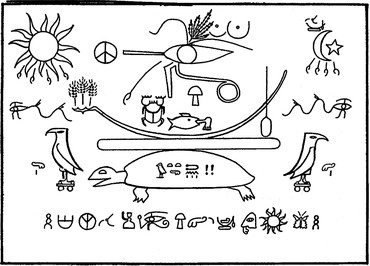

His latest book, published in 2020 by Brooklyn’s elegant small press Spuyten Duyvil, is A Life of Olson—a biography of the poet Charles Olson, told in verse and glyphs. The hieroglyph has fascinated Sanders since he took classes in ancient Egyptian at the New School in 1961, and he quickly saw how it could be adapted to his early imagistic style. I’m not sure how many poets are composing in hieroglyphs today; suffice it to say that he is preeminent within that small group.

Among Sanders’s many fans was the late David Bowie, who listed The Fugs, the band’s self-titled second LP (ESP, 1966), as one of his top twenty-five albums, noting, “This was surely one of the most lyrically explosive underground bands ever.”1 Bowie also listed Sanders’s Tales of Beatnik Glory as no. 78 on his list of top 100 books.2 Running to almost eight hundred pages, Tales of Beatnik Glory is a brilliant and sprawling collection of Chekhovian short stories chronicling the subterranean life of creative rogues on New York’s Lower East Side.

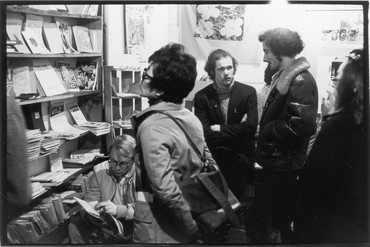

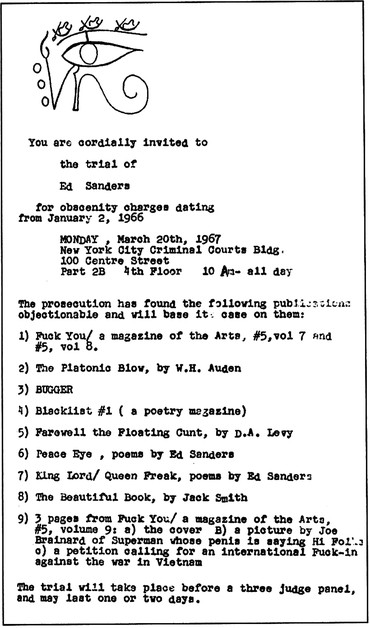

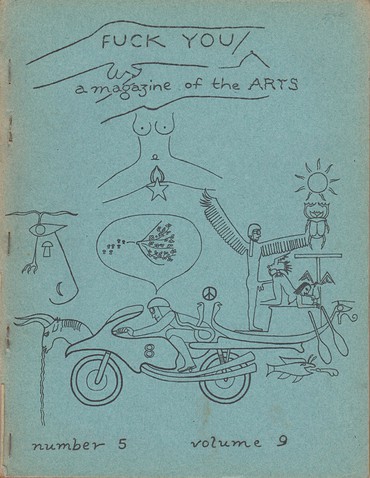

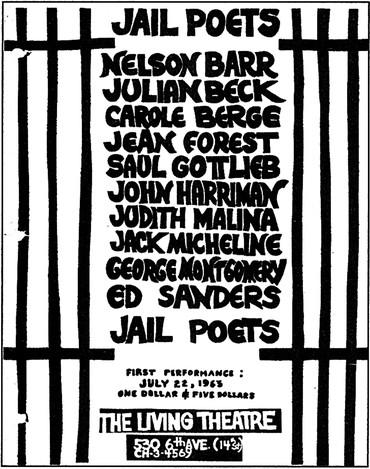

A pioneer of the mimeograph revolution, in 1962 Sanders began publishing Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts—surely one of the more eye-catching titles in the annals of literary appellation. In 1965 he opened the Peace Eye Bookstore at 383 East 10th Street, where the decor included four silk-screened flower paintings donated by Andy Warhol and hung as banners. Antiwar and legalization-of-marijuana activities regularly landed him on trial and in jail. As courtroom attire, his blue suede shoes particularly outraged Judge Julius Hoffman at the Chicago Seven trials in 1970.

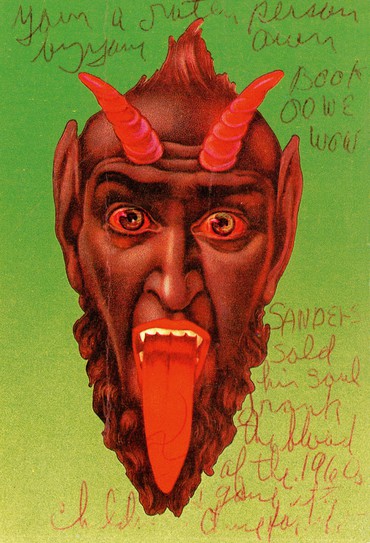

In the 1970s, close encounters with Charles Manson resulted in yet another underground epic, The Family (1971, revised third edition 2002). Since then Sanders has published dozens of books of poetry, history, journalism, and biography. He has released over a dozen albums of original material with The Fugs, in addition to eight solo records, including the genre-bending country-and-western albums Sanders’ Truckstop (1969) and Beer Cans on the Moon (1972).

The scope of Sanders’s work is daunting, so in this conversation I chose to focus on the unifying element behind it all: his vast archives. Since the 1960s he has been preserving the cultural artifacts that have passed through his spheres of interest. As a passionate researcher myself, I understand the talismanic power and unmediated narrative that historical objects possess and emanate.

Sanders met his wife, Miriam, at New York University in 1959. Miriam studied geology and Ed would graduate with a degree in ancient Greek. Sixty-one years later they are still together, living in a small cabin in Woodstock, where they moved in 1974 to raise a daughter, Deirdre. Here Sanders continues his work promoting the green agenda: historic preservation, zoning regulations, water rights, and conservation. Miriam’s book of nature essays and drawings, Our Woodland Treasures, was published in 2020 by Station Hill Press.

Raymond Foye How do you maintain your focus in the midst of so many diverging interests?

Ed Sanders You need to pare down what you do in the world. Compartmentalizing: I’ve done that pretty well. I’m able to build these Protestant walls to divide projects up.

RF Protestant walls? You mean your upbringing?

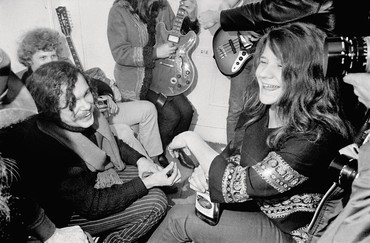

ES Yeah, my mother was very religious and taught a Sunday school class, like Janis Joplin’s mom taught a Sunday school class. Some of us wound up being pretty bacchic during our wild youths but some of us hung on to a certain discipline.

RF When did you first get a sense that you were going to keep an archive?

ES Early on in the 1960s I started saving things, mostly items that came to me in the mail when I ran a bookstore and a little magazine. First I discovered manila folders, which were very useful to keep track of things you needed. Then I was involved in the nonviolent peace-activist movement, which generated a lot of files that later became useful for court cases. Slowly I began building a history of all my activities, alphabetical and chronological by subject. But the real breakthrough came in the 1970s, when I discovered banker’s boxes, which are letter and legal size and very sturdy. You can stack eight of them on top of each other without them collapsing. So I began to measure out my life in banker’s boxes.

When I moved to Woodstock I acquired several baby barns that I’ve now filled up with my archive. I have a writing studio attached to our garage and I filled that up, and there are more archive boxes out in the woods in something called the duck barn. In the house there are numerous filing cabinets and boxes of active materials. I have well over five hundred boxes in my archive now. At a certain point it becomes a question of what should be excluded from the archive.

An archive is never done, it’s never complete. I have it all listed on a computer. My rule is to be able to physically locate any particular item within a minute or two: any photograph, any manuscript, any tape. When I can’t locate something I get very upset, but it’s very rare that I can’t find something immediately.

RF Was Allen Ginsberg an influence on the archive?

ES Yes, and Jack Kerouac too. You never would have thought that this rowdy gentleman had such a meticulous archive, but Kerouac kept everything very well organized, and he dated everything.

RF It’s always frustrating in an archive when you come across a poster or invitation and it says “May 15th” but no year. Of course it makes sense: when you get an invite in the mail, you know what year it is. But thirty years hence it’s a problem. The ideal archivist has an awareness of the historical moment, in present time.

ES Right. That’s another principle of archiving: you have to date every entry, every interview, every discussion. Every idea needs to have the date of when it was created, and to be labeled so it’s clear what it is. Because if you’re like me and you’ve done a bunch of things, over time a number of manuscripts can appear in an archive, and you don’t know who wrote them—there could be hundreds of manuscripts. I did a lot of work for the mimeograph revolution and lots of poetry came my way. Most poets are egotistic enough to write their names on all their poems, but in the ’60s there were a lot of space cadets who just handed in their poetry or songs and forty years later no one knew who they were. So the idea is to keep everything chronological, alphabetical, and subject by subject. And then I learned from William Burroughs, when I looked at some of his archives, he typed a description of what was in each box and taped it on the front, so I started doing that too. Because once you start moving archives around, it can get all scattered and rearranged, like pick-up sticks.

RF Every archive constitutes a history in itself—a kind of secret, unofficial history, doesn’t it?

ES In a way, yes. I guess an archive will ultimately be of value to scholars in the future, but in some cases just to a handful of scholars, maybe just one scholar, maybe two scholars. I had the galleys for William Burroughs’s novel The Wild Boys (1971) in front of me when I began writing my book on the Manson family, so I wrote my first ideas for the Manson book on top of The Wild Boys. Perhaps someday somebody will possibly make note of that. Or they won’t.

RF A commonplace item, because of its association, can have great import. At the Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa, for example, they have a simple white T-shirt stenciled with the words “Greystone Park State Hospital.” Somehow that T-shirt communicates the tragedy of Guthrie’s situation at that stage in his life better than any biographer ever did.

ES I have a pair of blue suede shoes in my archive that I wore when I testified at the trial of the Chicago Seven in 1970, and I have a gas mask from the Chicago riots. Oh, and when I went to congratulate Charles Olson after his Berkeley lecture in 1965, I noticed he’d drained a small hand-held bottle of Cutty Sark scotch, and it was lying there on the podium, so I grabbed it and there it is in my collection. It’s nice and small and it fits nicely in a file folder. Ultimately the question is what to keep.

It’s all just a flash of infinity—two hundred years will go by very quickly and whatever’s left of our archives will be our remains. It could end up being like an archaeological dig: an archaeologist can take a few potsherds and bronze buckles, the remnants of an old metal helmet and one or two embers of a three-thousand-year-old campfire, and voilà, they can hallucinate a book. Same with the sacred relics of the Beat generation, or the hippie generation, or the mimeograph generation, or the rock ’n’ roll generation, or the computer generation.

RF There’s an archaeologist named E. Breck Parkman who actually conducted a dig on the remnants of a California hippie commune called the “Chosen Family.”3 He excavated all kinds of debris, including record albums by Bob Dylan and the Beatles, but he also found records by Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand and the soundtrack album to My Fair Lady. Parkman concluded that “our species is a complex and diverse one and that those who believe that we can be subdivided into stereotypes are only fooling themselves.” What a marvelous summation. So in this regard, archives often stand against histories: the objects themselves may tell a very different story from the established accounts.

Speaking of archaeology, I’d like to ask about your obsession with Egypt and how that led you to think about hieroglyphs as a medium for poetry. You’ve adapted the glyph to your own uses in fascinating ways; by now it’s become a second language for you.

It’s all just a flash of infinity—two hundred years will go by very quickly and whatever’s left of our archives will be our remains.

Ed Sanders

ES In the late 1940s my mother used to walk me and my younger brother home from the movie theater in the little town of Blue Springs, Missouri, where we lived. After the movie we walked past the cemetery and I remember my mother telling us the story of the curse of King Tutankhamun—how all the archaeologists who opened up this tomb were later cursed with untimely deaths. I always remembered that. We had a wonderful art museum in Kansas City, the Nelson-Atkins, which had some Egyptian items. Later, when I came to New York City in 1958 to study at NYU, I became aware of these wonderful bookstores in Cooper Square and along Fourth Avenue, where I acquired some of the early books on Egyptology by Sir Alan Gardiner—really original scholarship. In the fall of 1961 I took a course in ancient Egyptian at the New School, taught by Joseph Kaster. Then when I was in jail in the late summer of 1961 for trying to board a nuclear submarine, I had an Egyptian textbook in my jail cell and all my memory cards for studying hieroglyphs—I made little index cards from the inside of cigarette packages, the hieroglyphs on one side and the translation on the other. Not long afterward I began to use what I called glyphs in my poetry. I started Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts in 1962, and there I started drawing Egyptian images and glyphs on mimeograph stencils with a stylus, mutating them to fit the language of the counterculture.

RF It sounds like hieroglyphs may be the future of writing. I suppose emojis are glyphs, but a fairly impoverished species. Your new Life of Olson seems to be the fullest realization of this concept so far. Exactly how do you see the glyph functioning in your work?

ES Well, gradually the glyphs evolved until I began to realize they weren’t just idle drawings I was doing. Ezra Pound uses glyphs in the Cantos, mostly Chinese ideograms. My sense of space in poetry, visually, was significantly influenced by photographs of Zen rock gardens in Japan, which seemed like living hieroglyphs. Another big influence was reading John Cage’s Silence, his arrangement of text on the page. I also related the glyphs to Henri Matisse’s cutouts, which he thought of in terms of Platonic images or “signs.” Many of my glyphs are arranged with words but some of them stand by themselves as visual poems. A glyph can be observed very quickly or can be an object of extended contemplation.

RF What is it about the persistence of Egypt—what makes it so compelling to people all these years?

ES It’s just a long river with a narrow civilization on either end, from the Delta south to Nubia. It had an interesting religion, the solar religion, which featured lots of human/animal transformations. But it was their artwork that remains so compelling and alive. When I started working with glyphs, I realized that one day in the future they would be able to move, to wiggle and change color—the ancient Egyptians believed the hieroglyphics on their shrines were actually alive. Matisse talked about the effect of color on emotions, and I realized that you could have color typography utilizing colors associated with certain mental moods. Long after my time here on earth, I think eventually hieroglyphs will go full color—not cartoons, but closer to literature. The human eye can detect something like four thousand different shadings of color, so why not utilize that capacity? There are interesting possibilities. I make a glyph just about every day, when the spirit moves me.

RF I know you were good friends with Andy Warhol, and he was a big supporter of your early activities.

ES When I arrived in New York City, in my late teens, I started going to all the art galleries and museums. Warhol silk-screened a bunch of flower paintings for the opening of the Peace Eye Bookstore in February 1965, and he sent a lot of people by. He was always in his own world, but he would often come to Fugs shows, and I would hang out at the Factory, although I more or less admired him from afar. One of the first Fugs songs I wrote, but never recorded, was a salute to Andy Warhol. I have a rehearsal tape of it somewhere.

RF So you really appreciated him at the time, as an artist?

ES Yeah, sure, he was a very sophisticated conceptual artist and he also had a great interest in the counterculture. I never went along with people who deprecated Andy Warhol, I thought he was an excellent artist. He was a highly skilled draftsperson, and technically extremely meticulous: I’d watch him touch up those silk-screen paintings very carefully, getting all the colors just right. The difference between whimsy and genius is sometimes imponderable. Warhol always had a clear idea about what to do next, and that was the difference between him and a lot of other artists.

If you’re in the avant-garde you can’t control the kind of people who want to hang out with you. I can remember being backstage at a Fugs show in Cleveland, surrounded by Hells Angels, and I realized you had to maintain your integrity and dignity and worth in the midst of whatever chaos happens. I think Andy Warhol was pretty good at that. I guess he would always go home to mother, which is probably a good idea.

RF Did you ever go to Claes Oldenburg’s storefront?

ES No, but I did go to many of the early Happenings.

RF Was that an influence on The Fugs?

ES It was an influence only because I realized you could rent a storefront and get a tank full of grapes, get a naked person to dance up and down on top of it, add a Fender guitar and amplifier and a smoke machine, and then you could charge admission. It was an updated version of a rent party. In the ’50s through much of the ’60s in New York, you could rent a pad for $50 a month, so you didn’t need much of a job to pay for that. It made it possible to earn a living through one’s art. That’s how The Fugs got going, playing in galleries. Then [the poet] Diane di Prima put us in the American Theatre for Poets on East 4th Street. The idea was to make a living, or a half a living, off your art, and the performance movement pointed a big purple arrow in that direction.

RF Do you ever reflect on what young artists are up against today in terms of society and capitalism, how to make a go of it, what it’s become? Any ideas about how you would get by if you were starting out, what it would be like, how it would be different?

ES It’ll always be difficult for an artist, between now and 20,000 ad. To do something like art or performance or music or painting, it’s not unnatural but it’s full of obstacles. First of all, you have to believe in yourself, you have to learn to trust your heart, and you just have to keep working on your art until you’re satisfied that you’re doing the best you can do given all of the gifts you have. And then you put it out there, and if it’s not accepted, then you have to decide whether you want to go on as a neglected artist. I always think there are a lot of Emily Dickinsons out there who just got turned off and don’t survive as great artists when they could have in different, more encouraging climates. It’s hard to know. And then to be impoverished like William Blake or Charles Olson or John Wieners, none of them were overfinanced. It’s a difficult thing even to talk about. It’s hard to know how many great artists are squashed out of the game while lesser people may have more pronounced egos, or the ability to withstand the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune and stay on their feet. You have to believe in yourself. Olson said you have to dare to be part of history, you have to enter the time stream in a historical way and make yourself known, but you also have to avoid arrogance.

RF Did you ever have any resentment toward the art world when artists started making really significant amounts of money and somehow the poets, because they didn’t make material objects, didn’t share the same success?

ES No, I always felt sympathy for inventors. An artist invents something in time, and they should be recompensed for their work. It’s true that some artists get ridiculously high prices for their work, but again, that can have to do with aggressive and pushy managers or agents. Because the more artists get paid, the more goes to agents and dealers, the same way as in real estate. I don’t know, there’s no easy answer. I don’t like to criticize creative people for making a living from their art, even if it’s excessive, because you’re dealing with capitalism, which is unnecessarily vicious.

1See David Bowie, “Confessions of a Vinyl Junkie,” Vanity Fair, November 20, 2003.

2See John O’Connell, Bowie’s Books: The Hundred Literary Heroes Who Changed His Life (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), p. 197.

3E. Breck Parkman, “Digging Olompali: The Archaeology of the Recent Past,” Society for California Archaeology Proceedings 30 (2016): pp. 175–82. Available online at https://scahome.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/15-Parkman-Breck.pdf (accessed September 14, 2020).

Photos and scans, unless otherwise noted: courtesy Ed Sanders and Granary Books