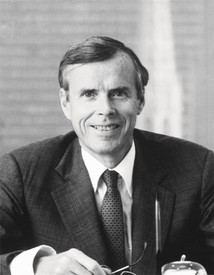

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 350 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

From October to early December 2006, Gerhard Richter’s studio in Cologne was the site of an intense painting process that led to Cage 1–6, a cycle of six large abstractions—a highly important group in the artist’s oeuvre.

In early 2007, I visited Richter during the filming of Corinna Belz’s Gerhard Richter Painting (2011) and we talked at length about his Kölner Domfenster (Cologne Cathedral Window, 2007), a seventy-five-foot-high stained glass window that fills the cathedral’s south transept. It comprises 11,000 hand-blown squares of glass in seventy-two colors derived from the palette of the original medieval glazing, which was destroyed during World War II. Half of the squares were sequenced by a random process, a ceding of control that suggests Richter’s interest in chance and in the submission of one’s will to forces beyond one’s control. His design takes its lead from his 4096 Farben (4,096 Colors, 1974), a square painting consisting of 4,096 small, different-colored squares. That work was itself the culmination of a visual inquiry begun with Zehn Farben (Ten Colors) of 1966, and continuing with a series of works based on the principle of the color chart.

After our interview, I asked Richter if he could show me his most recent work and we went to his studio, where I was lucky enough to be among the first to see the extraordinary Cage paintings. They were being readied for shipment to the 52nd Venice Biennale, curated by Robert Storr, where they were to be shown for the first time. Seeing them was an overwhelming experience: I was looking at one of the great cycles of paintings not only in Richter’s career but in the early twenty-first century.

As we were looking at the paintings, Richter explained that he did not yet have a title for them. Years earlier, I’d learned about his method for finding a title: choosing one significant word as a title is a repeated practice, often offering an initial explanation of the work. When we were organizing our first exhibition together, at the Nietzsche-Haus in Sils Maria, Engadin, Switzerland, in 1992, I suggested titles like Nietzsche and the Circulus Vitiosus Pictus. Richter’s method was more laconic: he asked me, “Where is the exhibition taking place?” I replied, “Sils Maria.” He said, “Too long.” So the title of the exhibition became Sils. During the studio visit in Cologne, when Richter wondered what he should call the new paintings, I asked him what music he had been listening to when he made them. His answer was “Cage.” There was a silence, and then he said, “That’s their title.”

This concise title could be unfolded into an extensive interpretation of these abstract paintings, but everything is already there in the short form. Like an explanation of a phenomenon, it unlocks the works, describing their relation to John Cage, one of the most important cultural figures of the twentieth century, and one who shared with Richter an interest in the great themes of chance and uncertainty. The title Cage can also be considered a visual association, since the six paintings have a hermetic, almost impermeable appearance. The title points to different layers of meaning and further speaks to their multidimensionality.

There are many relations between Richter’s work and Cage’s. Storr has traced them from Richter’s attendance of a Cage performance at the Festum Fluxorum Fluxus in Düsseldorf in 1963 to similarities in their artistic processes. Like Richter, Cage often applied chance procedures in composing, in his case notably through use of the I Ching. But there was nothing random about the chance events produced in this way; as Richter has pointed out, Cage made sure to set up his chance events in a way that would produce something worthwhile: “One can see, or rather hear, a great example in Cage’s work of how extensively, cleverly, and sensitively he treats chance in order to make music out of it.” Of his own work he told me, “These chance results are only useful because they’ve been worked out—that means either eliminated or allowed or emphasized; in short, brought into a particular form that’s skillful and artistic.”

In their large scale (over nine feet square) and dense materiality, the Cage paintings feature a variety of blocks and patches of color, lines, and areas of white, all fading into each other. To me these demand an infinite process of looking, since one can always discover new and different elements in them on each viewing. This process has a certain sense of slowness. It is as if Richter’s working process were reflected—continued, almost—in one’s repeated encounter with his works. Richter has compared his process to music, where notes are combined in such a way as to sound good or right or comprehensible, communicating something different from a verbal account. This is perhaps why the Cage paintings are beyond our comprehension, leading us to look at them again and again.

The thick layers of paint and the dense texture derive partly from Richter’s own technical invention: the use of a squeegee. By moving squeegees of different sizes (in this case a large one) over the canvas, sometimes slowly and carefully, sometimes more forcefully, he adds and subtracts colors and reveals the painting’s many layers, unveiling its multidimensionality. He chooses the colors on the squeegee but the trace that the paint leaves on the canvas is to a large extent the result of chance. “One doesn’t find many brush marks” in the Cage paintings, Storr remarks, “the squeegee is the main protagonist.” The result then forms the basis for decisions about how to continue with the next layer. As Richter says, painting happens. He seizes on these moments revealed by chance in a tension between composition and accident—a controlled chance, so to speak, like that found in Cage’s work.

Analogies with Cage also appear in other Richter works. Patterns: Divided Mirrored Repeated, for example, his extraordinary artist’s book of 2011, shows his experiment of taking a reproduction of his Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting, 1990, cat. rais. no. 724-4) and dividing it vertically into strips: first 2, then 4, then 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1,024, and 2,048, up to 8,192 strips. The strips get thinner and thinner throughout the process. The experiment then leads to the strips being mirrored and repeated, which results in a diversity of patterns. The outcome is 221 patterns published on 246 double-page spreads. Here Richter set the rules but didn’t manipulate the outcome, so that the pictures are again an interaction between a defined system and chance.

Other outstanding artist’s books of Richter’s include Wald (Forest, 2008) and Eis (Ice, 1981), which contains his stunning photos of a trip he made to Greenland. The layout of these books is sometimes interrupted by blank spaces, like pauses. Richter told me that his layouts have to do with music and silence, again recalling Cage.

As Richter says, painting happens. He seizes on these moments revealed by chance in a tension between composition and accident—a controlled chance, so to speak, like that found in Cage’s work.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

A performance of Cage’s Organ²/ASLSP (1987) is currently taking place in Halberstadt, Germany. “ASLSP” stands for “as slow as possible”; Cage offered no further instructions, so that each performance of the score is different. The actual performance will take 639 years to complete. The slowness of Cage’s piece is an essential quality for our time, in which, with globalization and the Internet, all processes are accelerated to a speed at which no time remains for critical reflection. ASLSP thus argues for the importance of liberating time.

Richter once told me that “picture-making consists of a multitude of yes/no decisions.” He finished the Cage paintings when there was nothing left to be added and nothing left to be destroyed/subtracted. The works’ seemingly never-ending process was suddenly finished “with a yes to end it all.” Like all of his most important works, the Cage paintings are heterogeneous models; combining observation, improvisation, and memory, they allow—even demand—perpetual change and mutation.

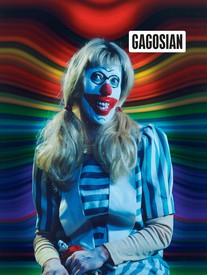

The presentation of Richter’s Cage paintings at the Gagosian galleries in New York and Los Angeles marks a particularly important moment, since Richter’s work has never really been exhibited in Los Angeles. The galleries will also show eight extraordinary recent drawings that further connect Richter with Cage. Drawings have accompanied Richter’s work as a painter from the beginning, an early example being his Elbe cycle of monotypes made with a roller from 1957. Later, in 1978, when he was on the threshold of beginning the abstract paintings, he made a cycle of important drawings in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Another intense drawing cycle took place in 1999, at the time of his first retrospective, at the Kunstmuseum Winterthur. A more recent group is November (2008), where the seepage of ink through the paper makes each work viewable on both sides.

Painting has certainly lain at the center of Richter’s practice, but as Dieter Schwarz pointed out on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition of drawings at the Louvre, Paris, in 2012, his drawings were never studies or sketches for paintings but independent autonomous works, produced in very concentrated working phases. Since 2017, drawing has for the first time moved to the forefront of his activity. His critical and self-reflexive practice in the medium includes the use of an eraser, perhaps in echo of his employment of a squeegee to remove pigment in his paintings.

What follows is an edit/collage of two conversations I had with Richter about the Cage paintings, one of which has never been published before. Here Richter himself makes a connection between his drawings and the Cage paintings when he says that early on, he “thought the paintings would have to be completely white, with very little adumbration—like large drawings in oil on canvas.”

Hans Ulrich Obrist Can we talk about the new Cage paintings? This is the first time this new cycle has been shown.

Gerhard Richter It’s a series of six large paintings, and they have a special significance for me insofar as I still don’t fully understand them. They were planned completely differently: I wanted to paint them from photos that I’d prepared two years ago, photos of various atomic structures comparable to the Silikat [Silicate] series of 2003 or the Strontium picture from 2004. These six photos promised beautiful, serious, somewhat disturbing paintings. And then when I’d begun the first painting, in late August, I suddenly lost the desire to work on it and proceeded to destroy what I’d already painted, to paint it over without being conscious of what I wanted and where I wanted to go. And I just kept on painting like this somehow. This peculiar state of hopelessness, perplexity, and high spirits kept on long enough for me to finish all six paintings. From time to time during the work, of course, I had fantasies about how the paintings could finally look. At one point, for example, I thought they would have to be completely white, with very little adumbration—like large drawings in oil on canvas.

HUOSomething like the large white paintings that were exhibited in Japan?

GRYes, something like that. These ideas always get me very excited, but usually they disappear the next day, or the next week. And then I’ll start up again, nonsensically. In this way they’re definitely my freest paintings. And I never, ever thought it possible they’d be finished; I had no concept of final results. But then they were finished, after three months, which meant there was nothing more I could do with them. I was almost upset.

HUOA sudden emptiness?

GRYes, that too. That’s often the case when something is finished, one feels superfluous and useless.

HUOHow do you know when a painting is finished?

GRWhen I have no more ideas about how to change it. When I can’t think of anything else to add, or even whether or not to throw it away. That also happens; it’s okay, and healthy, to throw things away. You have to get angry when you see the nonsense you’re making. And it will always be destroyed until you reach a situation when you can’t complain anymore, and then it just stays like that. But in this case, that finished state of the paintings came quite unexpectedly, in fact almost disappointingly. I think I’d felt I’d be able to—or would have to—paint them forever. In any case, they were done, and the next problem was that I didn’t know what the paintings showed, and how I could title them. And then you helped me with a question: you asked me what music I’d been listening to during that period, and I answered: Cage!

HUOAnd with that you’d found your title.

GRIn hindsight, I have to say rightly. Because just then I’d discovered, or rediscovered, Cage’s Complete Piano Music, and I’d been listening to it almost exclusively for a while. I still enjoy it today—around eighteen CDs, all of them with Steffen Schleiermacher—wonderful. Of course a title like that is only indirectly linked to the paintings; it doesn’t actually describe anything, it just guides one’s perspective in a certain direction, toward certain connections and similarities. But it’s also more than just a name. In any case, the title is meant to honor and express admiration for the music.

HUOCage has made an enduring mark on you. You once said that you were impressed by his “Lecture on Nothing”: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.”

GRYes, that’s true. Oddly enough, another connection just occurred to me, a visual similarity: yesterday I saw a postcard of this beautiful [Francesco] Guardi painting, Laguna grigia [1765], a wonderful little picture I’d seen once in Milan. I enjoy these kind of connections.

HUOAnd that brings us back to Venice.

GRInto the gray lagoon of John Cage.

HUOWonderful! Perhaps we can speak a bit more about Cage and chance. You’ve spoken often about the idea of chance in Cage’s work and in your own, and it seems to be the case that chance again plays a role in these unplanned paintings.

GRYes, a definitive role, even in the abstract paintings. Despite all my technical experience, I can’t always exactly foresee what will happen when I apply or remove large amounts of paint with the scraper. Surprises always emerge, whether disappointing or pleasant, in either case representing changes to the painting—changes that I have to process mentally before I can continue. One can see, or rather hear, a great example in Cage’s work of how extensively, cleverly, and sensitively he treats chance in order to make music out of it.

I can’t always exactly foresee what will happen when I apply or remove large amounts of paint with the scraper. Surprises always emerge.

Gerhard Richter

HUOYou’ve also spoken of Cage’s discipline. You were interested in the notion that chance is only possible with a great deal of discipline. The same applies to these paintings.

GRYes, otherwise they’d just be smears of paint. Even with the Farbtafel [Color Charts, 1966–74] and now with the cathedral window, these chance results are only useful because they’ve been worked out—that means either eliminated or permitted or emphasized; in short, brought into a particular form that’s skillful and artistic.

HUOCan I ask how the window began?

GRThere were ideas, such as depicting six modern saints—Edith Stein, for example, and others. I tried to put together a couple of little designs, only to realize that this wouldn’t work at all. And then, when I’d already mentally turned the project down, I found that this picture [4096 Farben] fitted the template so well that it really shook me, and I thought, yes, that’s it, I can offer them this. After that it took another two years for the cathedral’s chapter to agree to try it. That’s how everything came about.

HUOThe color charts started in 1966 and ran up to 1974. Can you maybe tell me something about how this series started? Was there a trigger?

GRWell, it had to do with the spirit of the time, the zeitgeist of Pop art, when these banal motifs were discovered—newspaper or advertising photographs, commercials. In my case it was the color charts in painting-supply shops: they were so perfect, all I had to do was copy them and there was my painting. The benefit was that it wasn’t as holy—I’m saying this a bit polemically—as those devotional pictures people used to believe in, something I always found highly disagreeable: this is a [Josef] Albers, and this is a certain play of color shades, this is an [Antonio] Calderara, and so on. To rebel against things like this is very important at that age [laughs]. Anyway, I just developed this further and systemized it. At first, each color was separated from the others by a bar, because I said to myself, You can’t let them touch, that looks just horrible. It was a step—today you can’t see anymore that this was supposed to be a step, but it was a step, and one that showed that it worked: you can put each color next to any other and it fits in almost all cases. And isn’t that truly anarchic?

HUOYou’ve said that your starting point was four rows of colors, red, yellow, green, and blue, and that their respective shades and degrees of lightness resulted in the color charts. Can you tell us a little more about this systematic scheme, and how you arrived at 4,096 colors starting with just four?

GRThe color charts in the shops were pleasant images—six nice shades of yellow, or a color scale for garden furniture—whatever. And then, because there are three basic colors, red, yellow, and blue, I started mixing them, three by three by three, divided into dark and light and into the next color shade. This produced paintings with 180 colors. For my taste, though, they all had too much of a red-bluish tint, and then I read somewhere that [Arthur] Schopenhauer had said that there were four basic colors—that green was one too, because it was so natural, or something like that. With that I was out of the woods! Now I had an alibi, and I simply took green into the basic color line. [Laughter.] And so the other paintings developed. It is actually very easy to do—four by four, by four, by four, and so on. And that’s why we end up with weird numbers like 1,024.

HUOYou bring up the realism that penetrates even into abstraction as such—you say that a certain part of it is always a narrative. This seems interesting in the context of the color charts, at least as a possibility.

GRYes, the eye always searches for “something” in abstract paintings, some similarity with real objects—that’s what creates the effect of abstract paintings. That’s why we can understand them. This kind of realism is always part of the color charts. With billions of sorting possibilities, an image will appear at some point—probably all images conceivable will appear. But the probability that I—or we—will produce an image is close to zero. They all look alike, always, one like the other, diffuse, not like an object. Everything is in there.

HUOAs a possibility.

GRYes, as a possibility.

HUOThe window project was a presence in the studio over the past few years, and a lot of other work developed in parallel with it—an entire series of abstract paintings, complete exhibitions. Were there overlaps, or are we looking at parallel universes here?

GRI think parallel, because the window project has a different origin, dating back forty years now. So it’s a field plowed “on the side,” which is no problem.

HUOIn earlier statements you often talked about atheism. Religion often turns up in the idea of art being a substitute for religion. Do you still think that?

GRYes, absolutely. We look at art with so much faith. In fact what resembles art the most is religion and faith. Nothing works without faith.

HUOWhen I saw the Cage paintings in your studio for the first time, you weren’t yet certain whether the cycle would have five paintings or six. It was as if the five paintings belonged together, but the sixth was a part of the series, yet also not. Can you say something about that? I believe all six are being shown in Venice.

GRYes, that question was solved in time, because the first painting quite obviously belongs to the series, even if its appearance is somewhat different, somewhat softer than the following five. It now has the sense of being an introduction. These new paintings are more spontaneous, more free, unplanned.

HUOSomething quite new is happening with the Cage paintings that wasn’t there before. Can we possibly encapsulate what it is?

GRThat’s hard for me to say. I’m glad that I’m gradually able to recognize what the paintings show, that something is being conveyed, that they actually depict something, something quasi-real. But it will take some time before I can describe what it is.

HUOYou once said that in your abstract paintings there’s a search for a likeness, which is always there.

GRYes, it’s always there. I think all abstract paintings function that way. We aren’t capable of viewing paintings without searching for their inherent similarity to what we’ve experienced and what we know. We want to see what they offer us, whether they threaten us or whether they’re nice to us, or whatever it might be.

We aren’t capable of viewing paintings without searching for their inherent similarity to what we’ve experienced and what we know.

Gerhard Richter

HUOIt’s very interesting that this cycle began, like many of your abstract paintings, with an image that was then destroyed. And there are several phases of images that you’ve documented photographically, so that we can see all the painted-over images that no longer exist. It’s actually a rather destructive act, and you agreed as we looked at them that this destruction is there, but that alongside it there’s the desire to create a well-built,

constructive painting.

GRYes, it’s quite exciting to work that way, with destroying, building up, wrecking again, and so on. That’s effectively a prerequisite—otherwise nothing will result. It’s different in figurative paintings; the destruction and construction aren’t as obvious there.

HUODo you think these are optimistic paintings?

GRI’m beginning to.

HUOI thought the gray paintings in your New York exhibition were much darker by comparison.

GRThe ones I showed in 2001 with Marian Goodman? They were actually a light gray, like bright dust and fog, but rather melancholic.

HUOSomehow the Cage paintings have a more optimistic quality . . . something of the principle of hope.

GRThat may lie in a certain aggression and unpredictability they have, which makes them more optimistic than the gray New York paintings.

HUOWe haven’t yet spoken about the light in these paintings—about cold light, warm light, southern light, northern light. How would you describe their light?

GR[Laughs.] Now that I’ve mentioned the Guardi, with its gentle southern light from the lagoon, I think I have to describe it as northern light.

HUOPerhaps that’s the paradox of the light in Engadin, where south and north collide, like Finland and Italy.

GRWonderful! Yes, Nietzsche described that so well. That’s exactly what it is: the light of Sils Maria.

HUORainer Maria Rilke wrote a wonderful set of letters as “advice to a young poet,” and I’d like to ask you what your advice is to young painters?

GR[Laughs.] Don’t be easily led astray, and don’t give up believing in art. That’s all.

HUOAnd a question that I always ask when I do an interview: Are there any unrealized projects?

GRVery few. When I have an idea, I start it. And when I have no idea, no one is the wiser.

After Gagosian’s exhibitions of the Cage paintings in Los Angeles and New York, the series will return to Tate, London, where the canvases are on long-term view, loaned from a private collector and philanthropist who has long been one of the most ardent supporters of the artist.