Mark Stevens is the former art critic of New York magazine. He has been the art critic for the New Republic and Newsweek and has also written for the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and the New York Times.

Annalyn Swan is the former arts editor of Newsweek and an award-winning music critic. She teaches biography at the Graduate Center of City University of New York as well as at the Middlebury Bread Loaf School of English.

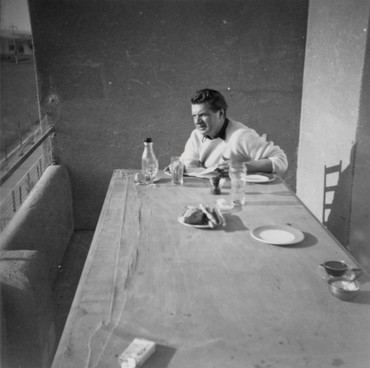

Stevens and Swan won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for their biography de Kooning: An American Master. They live in New York. Photo: Elena Seibert

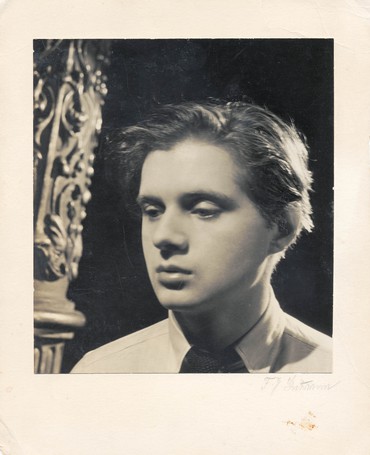

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including eight Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

Michael CaryLet’s start with how the project came about.

Annalyn SwanAfter our de Kooning biography was published, we were approached by several estates with proposals for artists we might like to write about. Bacon won out for two reasons. John Eastman, who is a copresident of the de Kooning Foundation, was collaborating at that point with the Bacon estate on various legal matters. One thing led to another and Brian Clarke, the head of the Bacon estate, signed off on the idea and has been very helpful to us ever since. So that’s technically how it came about. But from the point of view of why it was interesting for us: there was no comprehensive, thoroughly researched biography of Bacon. Nobody had actually done the boots-on-the-ground work, and there was nothing from twenty-five years ago until now, so it looked like a great opportunity to write about a remarkable artist, many of whose dimensions had not been explored.

Mark StevensAlso, both Bacon and de Kooning had a kind of emblematic importance—extending beyond the paint. Bacon is arguably the darkest artist of an often dark century, and that’s immediately interesting. He set the outer edge, in a way, for twentieth-century art. He also matters as an unashamed homosexual before gay liberation. And he had a powerful philosophical aura in that existential period; there are echoes of Samuel Beckett and other existential playmakers of the time. Plus, he created a celebrated persona in an age of celebrity. All interesting for a biographer.

MCSince much of the existing biographical writing on Bacon was written by friends and intimates, it inevitably contains elements of memoir; you end up with very, very subjective portrayals of Bacon in the literature.

ASExactly. We’re very grateful to Dan Farson [The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon, 1993] and Michael Peppiatt [Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, 1996] because both of them knew Bacon personally. But having said that, there are also limitations in that their books are based on the personality and the interaction and don’t necessarily take a dispassionate look at Bacon. Who is this man really? That’s what we were trying to come in and do.

MSBacon circulated in many different milieus, so people knew him in different ways and he could be a different person in different places. It’s too bad that we didn’t know him personally, that we could not call on that kind of visceral knowledge. At the same time, we could hope to navigate his life with some objectivity.

ASThat whole “Bacon, the great legend of Soho” narrative narrows him. There’s so much more to Bacon than that.

MCI love Farson’s book because it’s outrageous, but both of those books prop up the Bacon persona, right? Bacon’s persona has a huge presence in the popular imagination. So the subtitle of your book, Revelations—one of the revelations is that Bacon was a whole person.

MSThere’s a well-known observation by E. M. Forster about the importance of both flat and round characters in a novel. Bacon has been presented in an interesting but flat way, and what we wanted was to draw him in the round.

MCIt struck me when I got to your chapter “Performance Artist” that you very much deal with the Bacon “persona” in that chapter. It comes quite late in the book, so we’ve had five hundred or so pages of Bacon as a person before you address the persona in a direct way. It’s remarkable: you’ve arranged for us to be able to see the performance and the persona more clearly because you’ve given us the material to know him more intimately as a person.

ASThat chapter comes toward the end because as he grew older, the performance became more important to him. He had so many physical issues, emotional issues, anxieties. He was struggling. He maintained that indomitable facade at huge cost into even his later years.

MSStructuring the book that way lets you experience the evolution of a life. Bacon never wanted to appear vulnerable or weak, probably a consequence of his difficult childhood. So he developed a very powerful persona over time, with the help of David Sylvester and others. He was already beginning to do that in the ’60s, when the press started to approach him and people wanted to know more about his life. He was well-known then, but it wasn’t until the ’80s that his myth really began to inflate. So the “performance artist” in that chapter feels contemporaneous—it’s happening at that time, while having earlier roots. And as Annalyn says, it’s poignant because he’s painting himself up and performing and being outrageous in a way that also reveals weakness and vulnerability.

The persona is never fake news. It’s a vital part of Bacon, and we think it helped him make his art, it helped him get through the world. It’s intrinsic. It’s just that there’s much else.

MCYou never met Bacon, which seems an advantage—but would you have wanted to meet him? Would you have enjoyed going out to dinner with him . . . besides the champagne and the caviar?

ASWell, other than the fact that he could be immensely dangerous . . . shall we start with that? He could absolutely eviscerate his friends, so it was always a gamble to go to dinner with Francis Bacon. If he got too drunk, he could get mean and vicious. But when he wasn’t too drunk—and he often wasn’t too drunk—he could be the most marvelous, charming, entertaining presence. That was his best stage.

MS He had exquisite manners, unlike many artists and unlike many people. That’s one thing that he took from the privileged circumstances of his birth. The manners are wired into the sensibility.

ASBacon’s sister, Ianthe, told us that at one point Bacon said to her, “I’m so glad that I know where the silver is on the dinner table and that I learned manners.” Then Ianthe paused and said, “Not that he always used them, of course” [laughs].

MSDavid Sylvester said, “He was never rude unintentionally.”

MCYou said Bacon was perhaps the darkest artist of a dark century. Was it depressing at all to spend ten years of your life with this artist?

ASI have to say, we had such fun. Bacon had been kind of trapped in this myth as a so-called monster, and very English, but this was also a man who loved France and had many close friends there: he adored French intellectuals. His Anglo-Irish background was a whole new world and no biographer before us had actually crossed the Irish Sea and gone to Ireland, which is so revealing about his youth. We went to Dublin and visited all of these grand houses in the Pale, we learned everything we could about the horse-racing country and about the big-house traditions. It was wonderful. And we spent some time in Tangier . . . that was really tough [laughter]!

MSIt wasn’t depressing because Bacon wasn’t depressing. The reason he was so good at darkness was that he was full of light. You need light to make a shadow. He loved gambling, he loved conversation, he loved wine, and he was funny. One time in the 1970s he was gambling at the Playboy Club in London, playing roulette and losing badly, so he’s bitching and cursing and carrying on. One of the bunnies asks him to please behave. Bacon mutters, “Bunnies! What they need around here is more buck rabbits” [laughter].

ASThere’s a sort of a playfulness that just doesn’t translate into what most people think about Bacon. He didn’t take himself too seriously. It’s kind of unimaginable, the way he just flung money across the table, but it speaks to how wonderfully high-spirited he was, that he would just go for the gold, just go for whatever, just fling it all out there. Isn’t that an interesting character to pursue?

MSBacon thought most people were being cagey and holding back. He didn’t keep that kind of savings account. Most serious players of roulette develop these obsessive systems, but Bacon had no interest in that sort of safety. He had a kind of ancient Greek feeling for fate: he didn’t mind being struck down, he didn’t mind losing. At least then something was happening.

MCAnd he gambled with his work?

MSYes, he depended on chance in his work—gambling in the studio much as he did at roulette. He would take a chance and very often would ruin a portrait, for example, or upset an almost finished picture. He didn’t care, he would relish slashing it up and getting rid of it. You don’t always hit the jackpot when you put all your money on twenty-eight, you know? It doesn’t happen that often. It’s important to judge Bacon not by the lesser bets that escaped the studio but by his best work, which is like nothing else—and does hit the jackpot.

ASBacon was so judgmental of his work, so prone to destruction. Valerie Beston of Marlborough—“Valerie from the gallery”—her primary job was to intuit when Bacon had finished a painting so she could somehow coax it out of his Reece Mews studio and have it whisked off to the gallery in the van. And they would have to hide the paintings so when Bacon came into Marlborough he wouldn’t see them. He was so self-critical, he probably would have destroyed half of the surviving paintings had he had a chance.

MSRemember, Bacon was largely self-taught. An artist who has formally trained in a school is not going to screw up to the same extent that a self-taught artist might, especially in the treatment of the figure. Matisse and Picasso, both such fluently trained artists, they’re never going to make a really bad picture because they don’t know how to make a bad picture. Bacon is different. The self-taught aspect of his sensibility helps explain why he became a great original, but you can also sometimes see related weaknesses. John Richardson and David Sylvester and others, for example, have complained about the sometimes awkward relationship between the figure and the ground in a Bacon painting. People with an eye know that the ground is almost as important as the figure, the negative space about as important as the positive space. Bacon struggled with that. And the struggle sometimes led to terrific solutions, poignant and powerful and steeped in a sense of the terror of blank space. But not always.

ASThere was another advantage to being self-taught, which was that he experimented until he got things right. We write about his time in the village of Steep, in 1941 and ’42 during the war, when he takes himself away from London for two years. It turned out nobody had really looked into that period very much, for one reason: Bacon completely hid it. But it was the rough experimentation that he did hidden away in Steep that led to Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion [1944], his breakout painting. So there are periods in there when he just took the time to teach himself to go to the next level.

Working on Bacon was sometimes like walking into a Dickens novel. These characters! People don’t write nineteenth-century novels anymore, of course, but biographies can do something related in our world—be long, expansive, a little discursive.

Mark Stevens

MSHe was certainly what we would now call a controlling person—and that extended to his past. There are two periods in his life that he essentially erased. One of them is Steep and the other is when he was in Paris as a very young man. He was in Montparnasse in the late ’20s, surely the art mecca of the twentieth century. He never talked about it! It’s erased. He’s in Paris for a year and a half then and he says almost nothing about it? Why?

AS His time in Paris is fascinating because it was the beginning of his short-lived design career, which he completely buried later. He did everything he could to dynamite it out of people’s memory, but in fact he was very much plugged in to the design world then, on both sides of the Channel. It had been a mystery where Bacon’s very modernist design aesthetic came from, but it clearly came from seeing Eileen Gray’s Jean Désert showroom in Paris. He would have had exposure to Gray through a woman named Madge Garland, who was best friends with that whole group of designers in Paris. Madge was the fashion editor of British Vogue for four years in the 1920s while her lesbian partner Dorothy Todd was the top editor, and the two of them were the queen bees in the design and fashion world at that period. In a book Garland wrote later, she mentioned a room that Bacon had designed—a room for her, actually—but no writers had discovered this connection to Garland before. We asked John Richardson if he knew whether Bacon knew Madge, and he gasped, “Madge Garland!” and of course he was off to the races. “Yes, he knew Madge.” John described her—one of my favorite lines—“Madge Garland is the kind of woman who would move in next door to you if she thought you would be useful.” She was a connector [laughter].

MSAnd Bacon wanted to be connected. The remarkable thing about this, from a biographical standpoint, is that Bacon, at only eighteen years old, is already setting out on a very ambitious design career. Madge knew Virginia Woolf, she was very much interested in modernism and in bringing modernism to London. And she fastened on Bacon and Bacon accepted her as a mentor. So this is not a young and dissolute wastrel killing time, as Bacon would have you believe, but a determined young man looking for helpers and mentors, first in Madge Garland and then, back in London, in one of the chief modernist designers at the time, Arundell Clarke.

MCWe knew that Bacon designed a bit of furniture here and there, but it always seemed strange, because how does an eighteen-year-old manufacture furniture? It was never really elaborated.

MSAnd how does an eighteen-year-old get to painting without any training? It would have been intimidating, almost absurd, for an eighteen-year-old Englishman in Paris to start painting serious pictures in Montparnasse while Picasso was just down the block. What’s he going to do instead? He moves into the very powerful design world in Paris, which has English, Irish, and American figures. It becomes a natural segue. Once you gain some fluency in design and you get to know people, well, it then becomes easier to take a chance at painting to see what happens. The design is not just an interlude; it helps make possible the move into more serious painting.

MCDesign is also a profession, it’s a job. And a young man on his own who’s been cast out from the family has to figure out a way to make a life.

ASHe probably loved making money on his own. But he was also never abandoned by his family. Being “cast out from the family” seems to be another myth more than anything else. Decades later, Bacon’s sister Ianthe said, “Our mother never knew he was homosexual. She always said, ‘Oh, I hope Francis settles down and gets married.’ And our parents never threw him out.” And Ianthe would have known, there would have been something in the family legend. So again, Bacon is not the most reliable narrator.

MCThe relationship with Ianthe in Bacon’s later years really surprised me, and another of the revelations in your book is the extent to which a series of women played important roles in Bacon’s life.

ASIt goes all the way back to his grandmother, Granny Supple, the one he lived with in Ireland. She was the first woman to take up Francis apart from his nanny, who lived with him until her death, in 1951.

MSHe didn’t know other little boys when he was a child. He knew little girls. And then he moved on to women who were somewhat older than he was, who liked to help this charming boy.

ASHe had this ability to be close friends with women that gets overlooked in the Soho sacred-monster legend, which is very much a male narrative. But Madge Garland, Isabel Rawsthorne, Sonia Orwell, Janetta Parladé, Valerie Beston, Nadine Haim, and other lesser-known figures were powerful characters who were of enormous help to Bacon. And when you include them, another dimension of Bacon starts unfolding before your eyes. Generally he liked strong, tough women.

MSValerie Beston, for example, had that sort of no-nonsense “I’m not going to pity myself” English character. A bit Miss Marple. Stocky and sensible shoes. Bacon could be a bitchy gossip about his friends, including Miss Beston, but he also liked to keep his friends. One important revelation in the book is that he remained so interested, not just in rough trade and being a sexual alley cat, but in serious long-term relationships. He didn’t usually give up friends, and he didn’t give up lovers; he was even a bit clingy.

ASCompanionship and wanting companionship, that was really true throughout his life. And you see it particularly toward the end, with John Edwards and José Capelo. Both of them were sympathetic characters who were very helpful to Bacon in his waning years. So there was a cozy side too. Bacon really wanted the companionship, not just the S&M sex.

MSPeter Lacy never spoke publicly about Bacon, but we found two of Lacy’s nephews who knew him well and they were aghast at the traditional and caricatural portrait of him as a sadistic fighter pilot. They told us that he’d never been a fighter pilot. They presented him in the round. If you actually look at Bacon’s letters to his various friends and see his anxiety about Lacy, you can begin to piece together, almost forensically, that these two men simply never got over each other. Their relationship was tortured and sometimes violent, but also revelatory for each man. It’s nonsense to portray Bacon as a little vulnerable masochist and Lacy as a powerfully sadistic fighter pilot. They were together for ten years, on and off. That’s something.

MCThere’s a device you use throughout the book, where you punctuate the end of several chapters with a brief essay on a single significant work. How and why did you develop and deploy this device?

MSThere are a couple of reasons. One, if you’ve read a lot of biographies of serious artists or imaginative people, very often descriptions of their work—and their work is after all the reason the biography is ultimately being written—the descriptions of the novel, the symphony, or the ballet interrupt the narrative in a kind of gloppily glutinous way. You’re reading about something exciting in the artist’s life, maybe even his love life, and then suddenly you have to shift gears to read about the choreography of some ballet that you can’t see. And you just want to get back to the narrative. That’s unfortunate, because the ballet is actually more important than the sex life. So you’re sort of screwing things up in a fundamental way. We do discuss works of art within the text, but usually quickly, and these longer breakouts are a way to put some space between the life and the art. The device suggests that you must not reduce the art to the life or the life to the art—they can live together, but with some space, some oxygen, between them. It represents a kind of modesty about what one can and cannot finally know.

ASI teach biography- and memoir-writing at the Graduate Center of CUNY, in New York, and the first class starts with “Show, don’t tell.” Convey the character through anecdotes, through other people’s observations, and make the tough decisions to keep the narrative zipping along. One reviewer wrote that there’s a slightly picaresque quality to our book, which absolutely thrills us. We love that sense that you’re in an adventure, it’s almost like an early novel. When Bacon is young and at the threshold of his life, instead of just saying “Now he’s going off to London, he’s leaving home,” we ended the chapter by saying “He set out.”

MCSo what are some of your favorite biographies?

MSBiographies haven’t been very important to me, actually. Nineteenth-century novels are more the model, or that’s what I often want to take from a biography—that sense of a large, encompassing social landscape, with a flawed hero, intriguing secondary figures, and a strong narrative line. Working on Bacon was sometimes like walking into a Dickens novel. These characters! People don’t write nineteenth-century novels anymore, of course, but biographies can do something related in our world—be long, expansive, a little discursive. There’s such pleasure to be found in an immersive reading of a vital person’s life, from birth until death.

ASFor me, one of the best biographies has a truly original narrative style, The Quest for Corvo [1934], in which A. J. A. Symons went on a sort of detective mission to find out about this man named Baron Corvo. But then you can also write brilliantly, as Richard Ellmann did in his Oscar Wilde [1969], where everything sparkles and is witty in the way that he describes his character. He writes in the same spirit that Wilde wrote and lived. So I look at how you can make biography not boring; you have to find a way to reveal the character by degrees. By the end of the book, what you hope is that the reader has been fascinated, loved the story, and then has a real sense of the character. And so many biographies don’t do that.

MSBiography is portrait painting. It’s not only an earnest accumulation of facts, a piece of heavy baggage, an attic, a storeroom, an archive; it’s a reflection. And that means you leave some things out, put other things in, juxtapose magically. You work with figure and ground. There can be different kinds of portraits, but the good ones come alive, in the book and on the wall.