Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

There are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with black creativity.

—Bill Gunn, “To Be a Black Artist,” 1973

I think our artists have got to stop being so damned clear. But “clear” is not the word; it’s unjust to destroy “clear”: clear is good. “Flat” is what I’m trying to say. I want hallways, crevices, ditches, hills, and valleys. So I don’t expect you to go and understand it instantly. Just let yourself be taken on this artist’s trip. They’ll take you all sorts of places.

—Bill Gunn, interviewed by Clyde Taylor, 1982

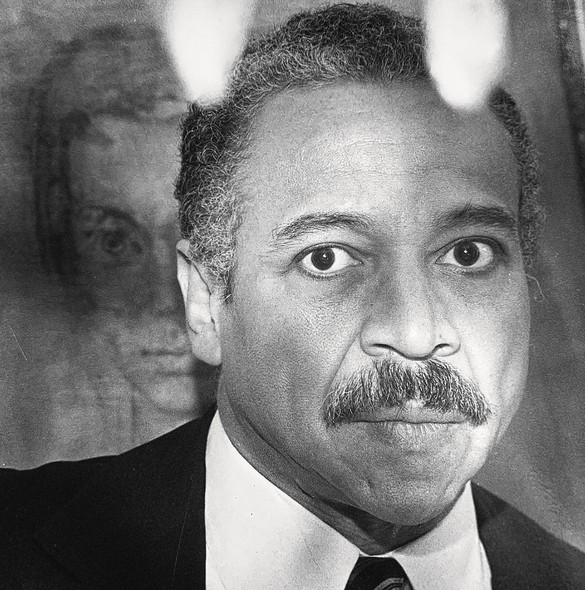

The world still hasn’t caught up with Bill Gunn. Throughout his life (1934–1989), he railed against and within institutions that rarely accorded him the respect or the space needed by this searing, maximalist visionary. But he never ceased to strive. Gunn built networks of solidarity, political and artistic (the two can never be separated).1 Today we have the proof in a body of work with which critics and public are still coming to grips: unpublished poems and short stories, novels, plays such as The Black Picture Show, an Emmy Award–winning teleplay, a subtly developed turn as the artist/husband in Kathleen Collins’s 1982 film Losing Ground, the scripts for two of the most audacious Hollywood films ever greenlit (The Angel Levine and The Landlord, both 1970), and three self-directed masterpieces (the never released Stop!, 1970, the classic Ganja & Hess, 1973, and the mammoth Personal Problems, 1980), toward which these notes on a Gunn poetics are aimed.2

Before continuing, we must reckon with that beastly process known as canonization. We must come to terms with the unseen violence of the process of posthumous recognition, especially as it pertains to women, nonbinary people, and artists of color. Although certain key allies, collaborators, and friends of Gunn are still alive to see the larger, too-belated recognition of his genius (runs in repertory cinemas, shiny home-video releases, lauds in major newspapers and magazines), Gunn himself is not. He died in 1989, at the age of fifty-four, of encephalitis and aids-related complications in a hospital in Nyack, New York, the day before his play The Forbidden City opened at the Public Theater in New York City.3 He lived to see neither the acclaimed restorations of his work nor the audiences flocking to see Collins’s Losing Ground, not to mention his own Ganja & Hess and his and Ishmael Reed’s Personal Problems (restored through the joint efforts of Jake Perlin and Kino Lorber).4 Nicholas Forster, a lecturer in African American and Film and Media Studies at Yale University, is currently writing a biography of Gunn. For all these milestones (pluses for us now), we must never forget that racist establishment types stonewalled Gunn throughout his entire life, and that he did not live to flourish in the current culture, which fetes him both for better (the restorations of his work) and for worse (a feckless push for diversity that neoliberally acknowledges his existence at the expense of serious engagement with his work). On October 27, 2020, Ephraim Asili—the director of one of the best films of 2020, The Inheritance—posted on Instagram that he was listening to Carman Moore’s soundtrack LP of Personal Problems: “So glad that Bill Gunns soundtracks are finally getting pressed to vinyl and that his films are getting way overdue recognition (they love it when we die first [Black man shrugging emoji]).”5

What happens when words like “rediscovered” are unhesitatingly applied to the work of Gunn, who was never gone to those who knew or saw or were there since day one? Where is the place of the Black artist who lives for the art of film but gets no love back from the cultural and industry gatekeepers who own the means of motion-picture production?6

It’s with these questions in mind that I use the fragment to absorb, breathe, glide across and within Gunn’s work. Why the fragment? In part, it’s due to a necessary push against grand narratives or moral meanings—against totalizing, against seeing one’s self mirrored and being content with the surface, against learning about where Gunn came from and whom he desired as a key to unlock the work. Such methods only serve to comfort the viewer with a false sense of wisdom, appeasing her desire to use the artist to “solve” the work. By contrast, the fragmentary look—which we can also call a poetic turn—evades such bland approaches to the work. Gunn himself: “Even though [what I do] is political I would like for it to be looked at as a true poem about me.”7 I am guided by Alexander G. Weheliye’s Black feminist complication of our understanding of race’s central role in “bare life” through his idea of “habeas viscus,” which “insists on the importance of minuscule movements, glimmers of hope, scraps of food, the interrupted dreams of freedom found in those spaces deemed devoid of human life.”8 These scraps and shivers of life can, indeed must, be gleaned within such dehumanizing spaces as the plantation, the ghetto, the camp. The cancellations that take place in such spaces are extended, as Gunn soon understood in the 1950s, into the Hollywood movie industry, where images of a knotty Black subjectivity are policed, watered down, or outright denied.

In the world of film, I can think of no other work that pays closer, more careful attention to Weheliye’s glimmers than Personal Problems—shot for shot, a masterpiece of dazzling proportions. As I’ve written before, this 165-minute, two-part film was originally broadcast as a late-night program on WNYC in New York and KQED in San Francisco, then requisitioned and rejected by PBS.9 Reed, its cowriter and executive producer, was hardly fazed: “We knew that we’d made a mark when, after a showing on WNYC TV, Vertamae Grosvenor boarded a bus and the driver greeted her by her character’s name, Johnnie Mae.”10 The film, which has sometimes been referred to as a “Black meta soap opera,” is a collaboration among a host of beautiful Black minds: the director Gunn, the writer Reed, the poet/producer Steve Cannon, and a cross-generational cast with deep roots in Black film history (headlined by Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor).11 Scenes are glimpsed in the life of Johnnie Mae (Smart-Grosvenor), a weary Harlem Hospital nurse who’s sick and tired of her long shifts, her cheating husband, her infrequent lover, her father-in-law, and the freeloading brother who crashes at her place in order to avoid a jail charge. Finding love in the city while bearing the omnipresent load of US racism, trying to ease the bitter tensions that divide precariously middle-class families over generations—seldom have such themes been lent so cool yet sweeping a treatment as in Personal Problems. It’s a work lined with fragments as diverse as daytime soap opera, New Orleans jazz, race films, Chicago blues, and the cathartic, funereal rawness of John Cassavetes (Husbands, 1970; Love Streams, 1984), individual shards that must be both dwelled in and read shot by shot—as in a poem where you may dwell upon one unstable word or rush madly across entire fields of action.

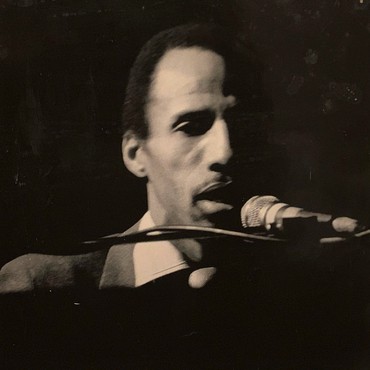

One such fragment: the performance of “Down on Me” for Johnnie Mae by her lover, the pianist Raymon (Sam Waymon, who wrote the song as well as performing it).12 Even as Raymon sits down, her hands prop up his back, as if to massage the voice radiating these tender notes. The Sony video camera eerily slows down the movement of her head as she bobs it to the side and weeps silently with Waymon’s divine delivery. As a result, we can see the traces of where she was before she moved, and of where she’s going after she’s already started to move. “Come crashing down,” he sings, “come crashing down.” For me, it’s the definitive filmic scene when you want to know what it’s like to be surgingly overcome with emotion in real time. For Gunn as for the Cassavetes of Love Streams, the only thing interesting is love, its irresistible call.

The loveliest touch in the scene, its button, is the length of a muscle spasm. It occurs when Waymon sustains the “me” in “down on me” for ages; all we see is Smart-Grosvenor’s face as she waits, along with us, for the natural end of the note. But it keeps going. And going. And still going. Once it does end, Waymon garnishes the note with a subtle melisma. At that, her eyebrow raises in surprise. In that one involuntary twitch, her body acts out the poetry she recited to Waymon a few scenes earlier: “They say if you are a true believer—that is, if the faith runs river deep in your heart—it’s possible, in the instant before the yucca-colored night gives way to dawn, to witness a cosmic freeze-frame.” In one twitch, Smart-Grosvenor avoids the “loss of the human” that occurs when somebody is “captured” by the too-perfect, too-neat image, instead existing in a choppy film flow.13 We can pause that twitch with a DVD player, rewind it and live it again and again, yet it will always escape the paltry explanations we fling at it.

It would be remiss to call what Gunn films “reality,” passive and generic. Reality in Gunn is not the mythic filming of life as capital-L “Life” lusted after by André Bazin—some kind of objective truth of cinema, the trace made into a monument of itself. Rather, the truth seen by Gunn and company appears to its audience in blips: precious as pearl daggers, or as the chipped ebony keys on which “sepia sambas” are composed.14 The fragments—the eyebrow twitch, a champagne glass at brunch lifted to underline a bit of gossip—cannot be assimilated into a straight plot, yet they are painstakingly toiled over. The fragments record skins and shades that weren’t envisioned as worth noticing with any delicacy by the makers of the Hollywood camera apparatus (Gunn: “We’re photographed like the side of a fence—we’re photographed so hard”).15 Twenty-nine-year-old white cinematographer Robert Polidori wields the camera with the intent of twisting the glamour apparatus against its racist origins.16 Polidori and Gunn reject a top-down approach to cinematic-image construction, following wherever the actors want to take the piece. As Polidori told Reed,

The way Hollywood works, they don’t like improvisations. They want the movie to follow a map. They get everything preplanned and precut so they can shoot with one kind of camera. You’re not jamming anymore. You’re playing the preset song, so the actors don’t get to take off. They have to mimic, so it’s robotic. But I was filming Personal Problems like improvisational jazz.17

Such a highly unorthodox method of filming bolsters (what else?) poetry, that incommunicable domain of the quotidian that swerves to avoid crashing into institutions of power and fixed meaning. Recall the shot in Personal Problems when Gunn pans down to Waymon’s shiny black spats tapping out the pulse to his “One to One.” A crazy, inspired pan! All the singer’s sighs, all the love of the sight of blue lilies, all the lusciousness and the longing for Johnnie Mae that fills Raymon’s stage on this night (for only a night?), all the Black voices building toward the climax together: they all crystallize into this one shot, the feet that scaffold and feed a roomful of crying faces.18 The shot cuts to the heart of the film’s notion of a human as unrepresentable yet defiantly present; in a state of restless, blurry forming; engaged in a film act rather than ending as a filmed thing.19

Such ontologies of process go beyond the concept of the totalized Man in art, that imaginary figure toward whom all creation tends, lazily, to be pitched. The struggle Gunn faced to communicate his Black aesthete’s vision of the world was one in which he tried neither to placate the white establishment’s notion of universality nor to buy into an African-American establishment notion of what Sylvia Wynter calls an “ethno-aesthetics,” a reinforcing of the cultural Imaginary (a white-inclined separatism, binary prone, and uninterested in mélange, the poetics of relation, or frisson and fracture).Where is the place of pleasure, of the unrationalizable punctums of life? Gunn had been intrigued by such excess since childhood. He loved Oscar Wilde, man of the epigram, and Alexander the Great spoke to him more than such staid historical figures as George Washington Carver: “Not only did they say that [what Alexander the Great did] was real, but it was fantastical too.”20 It’s not a big leap to connect Gunn’s acceptance of childhood phantasy to his adult hatred of an essentialized Man who denies that very same phantasy, the Black Man or Woman artist who must “speak to their race,” who must engage “the race question” and thus is refused the right to obfuscation. Gunn and company instead are invested in sonic textures, shattered scenes, errant colors, poetry, what the autonomist philosopher Franco Berardi calls “the excess of sensuousness exploding into the circuitry of social communication and opening again the dynamic of the infinite game of interpretation: desire.”21

Ganja & Hess and Stop! queer and trouble desire, returning it to the quarrelsome erotic sketched out by figures such as Audre Lorde and Jean Cocteau. It happens, again, through the fragment: the ring-finger glinting on Ganja’s toe as she gives in to the death drive, a glacial, bewitching shot that adds yet another dimension to a body falsely presumed to be understood. Or the moment when the blood-addicted anthropologist Hess (Duane Jones) squeezes a cherry open and the widow Ganja (Marlene Clark) dips her red fingernail into the vampiric ooze, sucking the nail, licking the lip, baring her sharp canines. What clinches the scene is the glockenspiel of the film’s main theme, “You’ve Got to Learn to Let It Go,” a demented lullaby sound like the la-la’s in Krzysztof Komeda’s score to Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Here Gunn takes us into the realm of the erotic, whose most precise definition comes to us from Lorde, cited by Marlo D. David in her wonderful explication of desire in Gunn’s Stop! and Ganja & Hess: “The erotic is the measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.”22 Where begins the ego, where the void? Partial answer: in between both gulfs, in a terrifying nowhere land where the rules of signification break down.

This is what guides Gunn. He can never take an assignment at face value. Given the signifier of vampirism (= Blacula, = cheap blaxploitation hit that bolsters the Hollywood regime, = business as usual), he breaks the contract that would only hire him out as a rhinestone sharecropper to unseen masters of mediocrity. It is the ultimate act of eroticization. As if playing with a Russian doll, he unnests the metaphors folded into vampirism: addiction to one’s own blood, addiction to capital, addiction to sex. Each is given a galaxy of moments, places, sensations: the Black church where a preacher’s hand against an addict’s forehead is the pathway toward a long-needed reckoning between body and soul; the coagulated blood pooling onto white tiles from a suicided Black assistant’s neck, lapped up by Hess as if parched at the end of a long exodus—only to start his longer death march into insanity.

What lingers in Stop!, a neo–Pier Paolo Pasolini psychosexual thriller on the basic mistrust that forms any one-to-one human equation (what Gunn films barely counts as “relation”-ships), is Gunn’s wild approach to space. Rooms are claustrophobic, bulging; the white lovers walk in and out of sight in ugly wide-angle views, while plan-séquences of their fights stretch on for merciless minutes without a cut. Gunn nails the irritable, lost quality of the main toxic relationship, its endlessness, which becomes the allegorical starting-point for the film’s journey: two straight white squares are set loose in Puerto Rico, meet a mixed Black/Puerto Rican swinger couple (the better half is Marlene Clark), and lose all sense of patriarchal ego in drug-fueled orgies that make Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice look like Full House. Outrageously, this movie has never been officially released. This major achievement of 1960s studio filmmaking has not been given the light of day by Warner Bros. Studios, despite the large following Gunn has commanded over the years. Waymon believes that an original print of Stop! is stored in the Warner Bros. archives, and a good print of the film played in 1989 at a posthumous retrospective of Gunn’s work at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. Perhaps readers might help in contacting Warner Bros. and asking them to release Stop! from the jail of obscurity in which this frightening, dense, sexy film has wallowed for now more than fifty years.23

The longtime disrespect accorded Gunn’s legacy is not simply a matter of distribution. When Personal Problems was rereleased in 2018, the New York Times naturally decided to review it for the first time. It was a Critics’ Pick. It was lauded for its “vitality” and “integrity” (despite “all its rough edges”—words to unpack). But out of this curiously distant appraisal, a telltale line slipped through: “Personal Problems contains not a single shot that can be called beautiful.”24 One would laugh if one were not so horrified by the casual racism here, masked under an identity-based appreciation begrudgingly, correctly doled out. By whose standards is it not beautiful? Whose beauty is even under consideration? What’s the standard: Quentin Tarantino? Marriage Story (2019)? For all my contempt for such a line, I refuse the balm of surprise. After all, it was in the Times that Gunn himself had to read a review of Ganja & Hess in which the reviewer left twenty minutes after the film started because he couldn’t understand what was happening, then decided to publish a full review anyway. In response, Gunn wrote “To Be a Black Artist,” an excoriating cri de coeur published in the Times as a letter to the editor that still speaks to us today. Gunn takes the paper and other like-minded publications to task for unchecked racist standards: “Another critic wondered where was the race problem. If he looks closely, he will find it in his own review.”25 Through language, Gunn’s lifelong medium, he exposes the annihilations and dehumanizations wielded by a petty-minded, misogynist critical establishment: “When I first came into the ‘theatre,’ black women who were actresses were referred to as ‘great gals’ by white directors and critics. Marlene Clark, one of the most beautiful women and actresses I have ever known, was referred to as a ‘brownskinned looker’ (New York Post). That kind of disrespect could not have been cultivated in 110 minutes. It must have taken at least a good 250 years.”26 So when I read a regular Times reviewer in 2018 still finding himself falling into the easy traps of the racist unconscious of US culture, we can only say that such disrespect extends a good 400 years more. It’s the kind of slip explained best by Diana Sands’s unforgettable line in Gunn’s Landlord script. When asked what she plans to do with her mixed-race son (the father is Beau Bridges), Sands gives voice to the fury of Bill Gunn: “I want him to be adopted white so he can grow up casual. Like his daddy.”

Why Gunn now? What do these ghostly video images of Black love, these grainy bootlegs of ’60s orgies, tell us about where we are going in the realms of love, politics, and art in these times of pandemic, acceleration, depression, state violence? In his seminal book The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance (2012), Berardi provides the start of an answer: “Since the 1980s, precarity has provoked a process of desolidarization and disaggregation of the social composition of work. Virtualization has been a complementary cause of desolidarization: precarization makes the social body frail at the level of work, while virtualization makes the social body frail at the level of affection.”27 Gunn’s films—whether he is in front of or behind the camera—restore the passion of the body tenfold. Bill Gunn, Black artist, transforms the symbols and the language that spurn us into action. It is the individual’s choice to listen. Whatever she does, with or without her, Gunn’s poetry continues to slide on, soaking in blue lilies and wet cherries, rambling ever forward.

1As regards this notion, I think in particular of Clyde Taylor’s essay “We Don’t Need Another Hero: Anti-Theses on Aesthetics” (1988) and its critique of the late-1960s Black Arts Movement in the United States: “The Black Aesthetic sprang from the Black Arts Movement and largely follows the description set out by Larry Neal: ‘The Black Arts Movement is the cultural arm of the Black revolution.’ The misleading influence of aesthetics is visible in this semi-autonomous conception of cultural production apart from social and material production. This self-concept of the Black Arts Movement, which reproduces the separate aesthetic realms of first-world institutions, surrendered vital dimensions of economics and politics to others.” In Mbye B. Cham and Claire Andrade-Watkins, eds., Blackframes: Critical Perspectives on Black Independent Cinema (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988), p. 81.

2In 2020, the Criterion Channel highlighted three films in which Bill Gunn was involved. I’d already seen and loved Ganja & Hess and Personal Problems, so the biggest revelation for me was The Angel Levine, directed by Ján Kadár, scripted by Gunn, and based on a story by Bernard Malamud. Harry Belafonte, Zero Mostel, and Ida Kami´nska all appear at the peak of their careers. Mostel is an aging mensch on welfare, whose wife (Kamińska, a Polish theater star, Oscar nominated as the Jewish widow in Kadár’s equally powerful Holocaust melodrama The Shop on Main Street, 1965) suffers a possibly fatal heart attack. God sends Mostel a Black Jewish guardian angel (Belafonte) to guide Kamińska to health and Mostel toward a miracle—that is, if Mostel chooses to believe in Belafonte’s gift. It’s a film about being pushed past belief in love, charity, and brotherhood when faced with the racist, classist, ageist big city. Would that all guardian-angel films were as tenderly textured as this, as sentimental without treacle.

3See Cynthia Davis and Verner D. Mitchell, “Gunn, Bill (William Harrison Gunn),” in Davis and Mitchell, eds., Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), p. 149.

4“The assignment of authorship to a single director has always been an illusion. To call this Gunn’s movie would be a misnomer that imposes the same language that has historically devalued the work of black artists. The dictatorial regime of the television writers room or the power granted by the director’s chair was dispersed among a group of artists that ranged from actors, poets, and writers to anthropologists, experimental filmmakers, jazz musicians, and models. As [actor Mizan] Nunes recalled, the project was the work of ‘outlaw artists’ and the cast and crew made their own rules. This is apparent in the concluding credits. Though the lead actors and director are delineated and there is a note that the project began with ‘an original idea by Ishmael Reed,’ other roles were fluid and less clear. Throughout the production actors served as editors and producers when needed just as writers became assistants when necessary.” Nicholas Forster, “Improvisational Jamming: The Process and Production of Personal Problems,” Metrograph. Available online at https://metrograph.com/improvisational-jamming-the-process-and-production-of-personal-problems/ (accessed December 10, 2020).

5Ephraim Asili, Instagram post, October 27, 2020. Available online at https://www.instagram.com/p/CG2YdSIlE4w/ (accessed December 10, 2020).

6With The Inheritance—much like Garrett Bradley with Time (2020) and RaMell Ross with Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018)—Asili extends the tradition forged by Gunn and other Black artists of his generation (St. Clair Bourne, Kathleen Collins, Ivan Dixon, Melvin Van Peebles): a fantastic reveal of the gaps in language, the thrill of grainy and knotty texts, le gai savoir.

7Gunn, in Hector Lino, Jr., “Black Picture Show,” interview, in Impressions: A Black Arts and Culture Magazine 1, no. 2 (Spring 1975), p. 8. Available online at www.graffitiverite.com/Bill_Gunn_Interview.htm (accessed December 10, 2020).

8Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), p. 12. Weheliye critiques what the philosophers Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben theorized as “bare life”—life before it is integrated into “good life,” into a sociable, political order—by centering our understanding of the biopolitical within race and Blackness. “Bare life” is an exclusionary category whose explicit and eventual goal is an eventual inclusion in the biopolitical order—one based upon death and destruction—that governs how modern neoliberal capitalistic society is organized. Agamben pays attention to the deleterious effects of establishing a bare life in contrast with a “good” (complete) life: “The realm of bare life—which is originally situated at the margins of the political order—gradually begins to coincide with the political realm, and exclusion and inclusion, outside and inside, bios and zoē, right and fact, enter into a zone of irreducible indistinction.” He warns that “until a completely new politics—that is, a politics no longer founded on the exceptio of bare life—is at hand, every theory and every praxis will remain imprisoned and immobile.” Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, 1995, Eng. trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), pp. 12, 13. In striving for that same “completely new politics,” Weheliye’s nuanced critique of Foucault and Agamben points out the totalizing theorization of a capital-M “Man” that lurks beneath their formulations. The latter two take, as their ubiquitous modern example, the Nazi concentration-camp victim, labeling the degradation of subjecthood and individuality within the space of the camp an “exception” to the polis, and in the process taking for granted the quotidian existence of the Black subject as always already within a state of exceptio in otherwise “ordinary” circumstances (living within policed neighborhoods, with higher and earlier mortality rates, etc.). It is with this in mind that Weheliye turns to Black feminist theorists such as Hortense Spillers and Sylvia Wynter, as well as to the literature of Toni Morrison—whose thinking I, too, keep in mind in the course of this essay.

9Carlos Valladares, “Personal Problems,” Film Comment 55, no. 1 (January–February 2019), pp. 46–47.

10Ishmael Reed, “The Black Artist Hollywood Couldn’t Buy,” Criterion.com, August 27, 2020. Available online at criterion.com/current/posts/7073-the-black-artist-hollywood-couldn-t-buy (accessed December 14, 2020).

11In addition to her starring turn in Personal Problems and other film appearances including Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Jonathan Demme’s and Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1998), Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor is perhaps best known for her revolutionary work in food writing and culinary anthropology. She was born into a Gullah family in South Carolina, was active in the Black Arts Movement alongside Amiri Baraka and Nikki Giovanni, and wrote the classic cookbook/memoir Vibration Cooking: or, The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl (1970). Dash is currently directing a documentary on Smart-Grosvenor’s book and her legacy. Says chef Thérèse Nelson, the founder of the Black Culinary History project: Smart-Grosvenor “showed us that when you break down a culture through its food, you cut through a lot of nonsense and get to the truth much more clearly than any other medium. The book starts from a space of fullness and asks that we see the genius in this culture in a world that is built to diminish and marginalize it. Her work wasn’t about acceptance or translation for the mainstream as much as it was about killing the myth that we were less than. Her work blew my mind because it was so rooted and so specific, and didn’t need to qualify itself.” Quoted in Mayukh Sen, “Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor Is the Unsung Godmother of American Food Writing,” Vice, February 20, 2018. Available online at www.vice.com/en/article/evmbwj/vertamae-smart-grosvenor-vibration-cooking-profile (accessed December 10, 2020).

12Sam Waymon, the brother of Nina Simone, composed the score to Gunn’s Ganja & Hess and played a supporting role in the film as the Preacher, who doubles as narrator.

13Judith Butler, “Precarious Life,” in Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006), p. 145.

14“Pearl daggers” is a reference to Ganja & Hess, where Dr. Hess is infected with a thirst for blood from a stab wound he receives from an ancient dagger. “Sepia sambas” comes from a poem that Johnnie Mae recites to Raymon in a garden, which was Gunn’s own: “They say that ebony rumbas, sepia sambas. The dance of the colors is so splendid that even the lemon-colored sun is dazzled, laid back, waits her turn. And baby blue and apple green have no shame jitterbugging on the clouds. And when quiet gray shakes her magenta, even the wind won’t behave.” Later, Johnnie Mae is interviewed by an offscreen voice (Gunn) who asks her to recite the poem she has been composing. She complies, then begins reciting the first words of the poem above: “They say if you are a true believer—that is, if the faith runs river deep in your heart.” She then goes on, however, to recite a completely different set of lines: “it’s possible, in the eyelids of one of these mornings, that you, too, will witness this exotic vision. And the wind, heady with the perfume of the colors, will tickle you. Do not laugh, weep, for, from dawn to dusk, anything can happen.” Gunn lets both poems stand as definitive works-in-progress.

15Gunn, in Taylor, “Bill Gunn: Climbing the Seven Monied Media,” interview, Black Renaissance/Renaissance Noire 10, no. 2–3 (Fall/Winter 2010), p. 102. The original interview was conducted in the summer of 1982.

16For more on racial biases in film-camera stock see Ann Hornaday, “‘12 Years a Slave,’ ‘Mother of George,’ and the aesthetic politics of filming black skin,” Washington Post, October 17, 2013, available online at www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/movies/12-years-a-slave-mother-of-george-and-the-aesthetic-politics-of-filming-black-skin/2013/10/17/282af868-35cd-11e3-80c6-7e6dd8d22d8f_story.html (accessed December 10, 2020), and Rosie Cima, “How Photography Was Optimized for White Skin Color,” Priceonomics, April 24, 2015, available online at https://priceonomics.com/how-photography-was-optimized-for-white-skin (accessed December 10, 2020). Hornaday writes, “Filmmakers working with celluloid also need to take into account that most American film stocks weren’t manufactured with a sensitive enough dynamic range to capture a variety of dark skin tones. Even the female models whose images are used as reference points for color balance and tonal density during film processing—commonly called ‘China Girls’—were, until the mid-1990s, historically white.”

17Robert Polidori, quoted in Reed, “The Black Artist Hollywood Couldn’t Buy.”

18I centralize the face, then flit away from its explicitness, in the manner of Butler: “To respond to the face, to understand its meaning, means to be awake to what is precarious in another life, or, rather, the precariousness of life itself. This cannot be an awakeness, to use [Emmanuel Levinas’s] word, to my own life, and then an extrapolation from an understanding of my own precariousness to an understanding of another’s precarious life. It has to be an understanding of the precariousness of the Other. This is what makes the face belong to the sphere of ethics.” Italics mine. In Butler, “Precarious Life,” p. 134. With Personal Problems, Gunn films a plentitude of Black faces, which neither the big nor the small screen had ever tried to meet head-on before, whilst going beyond the face, locating Butler’s and Levinas’s face in feet, in the soft undulating waves of the upper Hudson River, in the kicking legs of a waiter (Marshall M. Johnson III) who practices his aikido moves while working, in clouds clearing over the sharp wake of a Black funeral: i.e., in all the shards, human and nonhuman, that make movies move. Butler, again: “The face, if we are to put words to its meaning, will be that for which no words really work; the face seems to be a kind of sound, the sound of language evacuating its sense” (134).

19For more on the film act and the open-ended film that is formed as much by what’s traditionally constituted as “the viewer” as by “the author,” see Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, “Toward a Third Cinema,” Cinéaste 4, no. 3 (Winter 1970–71), pp. 1–10.

20Gunn, in Lino, “Black Picture Show,” p. 2.

21Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, intervention series 14 (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012), p. 21.

22Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic,” in Sister/Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984). Quoted here from Marlo D. David, “‘Let It Go Black’: Desire and the Erotic Subject in the Films of Bill Gunn,” Black Camera 2, no. 2 (Spring 2011). Available online at www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/blackcamera.2.2.26 (accessed November 11, 2020).

23I was able to see Stop! through a bootleg leaked in the spring of 2020 by an ardent cinephile, apparently from the VHS copy that was screened during a Bill Gunn retrospective at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2010.

24Glenn Kenny, “‘Personal Problems,’ a Look at African-American Life in 1980 New York,” New York Times, March 29, 2018.

25Gunn, “To Be a Black Artist,” New York Times, May 13, 1973.

26Ibid.

27Berardi, The Uprising, p. 128.

For Moira Fradinger, Pamela Lee, and Kobena Mercer.