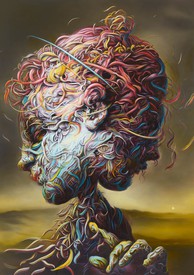

Mining art history and popular culture, Glenn Brown has created an artistic language that transcends time and pictorial conventions. His mannerist impulses stem from a desire to breathe new life into the extremities of historical form. Through reference, appropriation, and investigation, he presents a contemporary reading of images new and remembered. Photo: Edgar Laguinia

Jacky Klein is an art historian, author, and broadcaster. She worked as a curator at the Tate, Courtauld Gallery, and Hayward Gallery in London before moving into art publishing at Thames & Hudson, Phaidon, Tate, and HENI. An associate lecturer at the Courtauld Institute, she is the author of a number of best-selling art books and regularly appears on the radio, on TV, and online, including for the BBC, Bloomberg TV, Sony, and Christie’s.

Jacky KleinYour painting has undergone a major shift in recent years in terms of your process, and I understand you stopped painting altogether for a time, to delve deeply into the world of drawing. What sparked that desire for change, and what impact do you feel it’s had on your work?

Glenn BrownI accidentally abandoned painting for a few years, because I felt I wasn’t properly going forward. I knew that drawing was the fundamental building block of all good composition and all good painting, and I couldn’t go to the grave not having learned a bit more about it. So I came into the studio one day and just thought, “Today, I’m going to do nothing else but draw.” I carried on for about two and a half years.

The first drawings I made were awful, but they slowly got more accomplished as I learned what to do—and what not to do. The technical part wasn’t so complicated: it was just learning how you make a beautiful line, and how you make that line go with other beautiful lines to create something that is intriguing—maybe ugly or entertaining, but that keeps your eye moving around. I was working in black and white, just using line, no shading at all—yet those simple elements are very hard to get right, to weave into an interesting drawing that feels as if it has three dimensions to it.

JKThere’s nowhere to hide in a drawing, is there? They’re stripped back, exposed—and also potentially exposing.

GBYes, exactly. You can’t blur the edges; you can’t hide behind color, which is an easy way to hide lack of talent. Just turn the color volume to ten and nobody will notice that the composition’s not as good as it should be. But with a drawing, especially a line drawing, the composition has to be well-balanced and rigorous.

JKWhat’s the difference for you between a drawing and a painting? It seems not to be about medium, in that you use acrylics for your drawings, and you work on panels as you do with the paintings.

GBYes, and I draw with a brush as well.

JKSo what is the dividing line for you? What makes something a drawing?

GBIt’s about lack of color and lack of shading. Obviously, you can make a drawing from just shading: some [Georges] Seurat drawings have no line—they’re all shading with no hard edges. But to me, drawings are about just using line. It’s like the difference between a full meal and a snack: a painting feels like a full meal with all of its courses. It can be soft and hard. You have the different textures and colors, and the different taste sensations all mixed together, and by the time you’ve looked at it, you feel quite full; you’ve even had the dessert course to round things off. A drawing is a snack or an hors d’oeuvre—fast food. Which can be just as satisfying, but it’s not as complex to create, or consume.

JKOr to digest . . .

GBYes. A good painting should take a little bit of digestion, a little bit of time to recover from. That’s how I try and gauge whether something is a painting or a drawing.

JKIs there an element, too, of making work that sits precariously between mediums, in the way that your paint-encrusted sculptures sit between sculpture and painting?

GBYes. I make lots of work that is stuck halfway between painting and sculpture, and, likewise, work that is stuck halfway between painting and drawing. And some is stuck halfway between painting and photography as well, because photography influences my painting an awful lot. I like things to be between different states, and if they question the medium, that’s all good.

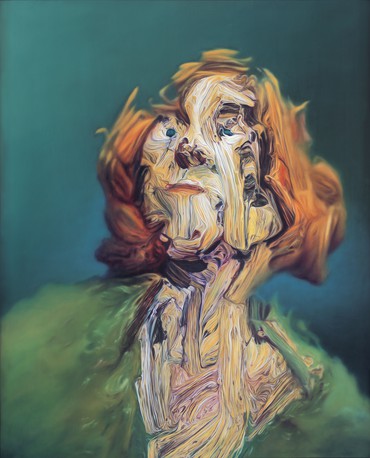

JKTell me about your most recent painting, Touch the Flaming Dove—we’re sitting in front of it here in the studio—and about its relationship with the recent drawings.

GBThis is the only painting I’ve finished so far in 2021. I spent last year concertedly trying to turn the drawings into paintings. It’s taken me about eight years to do it; I would keep trying to add color to the drawings and it never quite worked. I knew the whole point of me stopping painting to draw was to fundamentally change the way I make paintings. With my previous paintings, the starting point was a photograph of another painting which I projected up: sometimes it was gridded, sometimes I even painted over the printed image of that source painting underneath—but I was fundamentally reproducing a photograph of a painting and then heavily changing it. With the newer works that I began in 2020, the starting point is very definitely a drawing. It’s the skeleton, to which I then try to apply color, texture, and flesh. Most of the works are figures or portraits, so I’m literally hanging skin, sinews, and muscle on the drawn lines.

It’s been a very interesting time for me. I think to some extent I succeeded about halfway through last year, when I broke through that barrier to find a new way of creating my paintings. Now, the work has moved from being either painting or drawing, and is becoming a synthesis of the two.

Touch the Flaming Dove is one of the first paintings that really joins together drawing and painting, and therefore it has a different feel from my older paintings. It’s much crisper, slightly more graphic. There’s a greater sense of translucency, of seeing through the object. Because one of the interesting things about the drawings is that you can always see through them, even when they have two or three elements overlaid on top of each other: there will be two or three heads that you see simultaneously. The difficulty with the paintings was to try and make all of that coalesce into feeling like it was one solid object but still had numerous dimensions and layers to it.

JKWhen you say that the recent paintings begin with drawings, talk me through the process. You’re still looking at art historical images that you come across in reproduction, but now you’ve been translating them into drawings first, which you then use as the basis of the paintings?

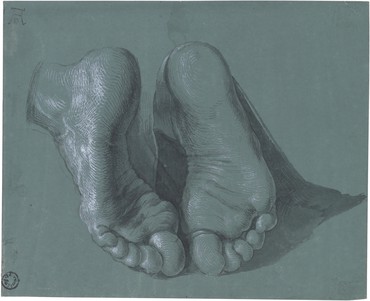

GBYes. I still use photography in the sense that the starting point is still a reproduction of a painting, or in this case, a drawing. The original here was by Albrecht Dürer, his Study of Two Feet from around 1508. I put that on a computer and played around with it on Photoshop: I stretch and cut things up and turn them upside down. I then made a small drawing on panel based on the Dürer image. It was made to be the cover for a book, for an exhibition I had last year in Berlin; the plan was that the black elements would be printed in black, and the white elements would be done in gold leaf. I didn’t finish it, because I realized that the image didn’t go with the exhibition—it felt slightly morbid and grotesque while the show was more toward uplifting science fiction. But it started the process of me then making the larger painting, because I thought, “Oh, this works compositionally rather nicely.”

JKAnd of course, importantly, you’ve inverted the feet.

GBYes, the feet are turned the other way up. In the Dürer, they’re the feet of an apostle praying, seen from the back, with the toes pointing downward, whereas in mine, the toes point upward. The symbolism of that is quite obvious: that the person somehow seems alive in the Dürer drawing, whereas in my painting, I’ve killed them.

I’m not trying to be Dürer. I’m just trying to be a bit of Dürer, perhaps with a bit of Dalí, for the twenty-first century—which is good enough for me.

Glenn Brown

JKThe blue celestial backdrop also creates a sense of the otherworldly, of not being tethered to the earth, literally not being “grounded.” I’m interested to know what it was in this Dürer drawing that particularly spoke to you?

GBDürer’s drawing capabilities are second to none. If you are interested in line drawings, then he is in many ways the pinnacle. His etchings are miracles: the sense of detail in them is extraordinary. He was obviously using magnifying glasses to make them, and with the etchings especially, he must have had help—a group of people who were so incredibly skilled—to create these parallel moving lines that change in thickness and weight as they move across the surface of the paper. They are technical tours de force in terms of what you can make line do. So, of course, I had to go to Dürer. And once you go to Dürer, then you go to Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert, artists whose drawings and etchings are also phenomenal.

That period of Northern European Renaissance art is particularly appealing to me, because it was freeing itself from the constraints of the Church. More people were educated and literate. It saw the birth of oil painting as well—and what was going on competitively between Holland and Germany was just extraordinary. It really was the golden age of art in many ways. Drawing never got better, and it never will, I think, because that competitive element and the mastery of technique no longer exist.

I’m not trying to be Dürer. I’m just trying to be a bit of Dürer, perhaps with a bit of Dalí, for the twenty-first century—which is good enough for me.

JKIn terms of the central image itself, the feet—you’ve painted feet many times before. What’s the enduring appeal?

GBThey’re the most downtrodden bit of us—the bit that we hide. In many Asian societies, to show the soles of your feet is considered very rude.

JKAnd art history throws out some wonderful examples of controversial feet in paintings—I’m thinking, for example, of Caravaggio, whose depictions of the dirty feet of saints, based on his studies of everyday laborers, became a sort of political and religious calling card, a symbol of his rebellion against convention.

GBTo paint Christ with dirty feet was a revolutionary thing to do. To show the dirt, that he was a real human being, was shocking because it shows that none of us is perfect. But in terms of Christ, you also have the imagery of the nails going through not only his hands, but his feet. And there’s the washing of the feet as a way of indicating that you were cleansing somebody, that you were helping them.

JKThe famous [James] Gillray print of gout also comes to my mind, with the devil launching his fangs viciously into a swollen big toe. The foot has had a range of symbolic functions for artists: as a sign of illness or decay, of the abject or base; as shameful or improper in some way. These all seem to be ideas you’ve played with and subverted over the years.

GBI was also working in response to Georg Baselitz’s paintings of feet and limbs. He was looking not just at Dürer, but also at Adolph Menzel. There’s one beautiful painting by Menzel of the artist’s own foot, which I’ve used on a number of occasions. In fact, the background for Touch the Flaming Dove is copied from my painting War in Peace [2009], which is in turn based on a Menzel.

JKYou’ve talked before about how portraiture is the central thread that runs through your work, and many of your paintings take the head as their focus. Do you see the feet in a way as portraits too?

GBOh, very definitely so. They’re very personal, very specific. The scars you get on the feet are like the scars you have on the face: the blemishes, wrinkles, and signs of history that the feet have on them are just as telling as the signs you find on somebody’s face—in fact, more so, because the shoes you wear over the course of your life affect the way your feet look. These obviously aren’t the feet of somebody young; they have age and history, and they’re proud of that history.

JKYou certainly convert them into something majestic and iconic in this painting, in terms of its scale and also the foregrounding of what might usually be seen as a hidden part of the body, particularly the aging or dying body.

GBThere is also an eye in there. It’s not a literal eye; it’s ambiguous—but I’m encouraging the viewer to see one of the feet as possibly a head as well, so it does become a strange portrait, a face that could be looking back at you. All of the feet I’ve done to some extent have that feeling that they could metamorphize into something else. The idea that the object isn’t stable is very important—that you can conceive of it as changing into a head or an animal or a human.

JKCan you say something more about the painting’s background, and about the relationship more broadly between figure and ground in your work? The background seems to me to be where the conversation with photography especially comes in, the idea of focus and blurring. Your backgrounds are really distinctive—as distinctive a part of your work as your inversions and curlicued brushstroke. Of course, one thing the drawings don’t have is a dense, worked background; they simply use the color of the paper or panel as the base on which you create your images.

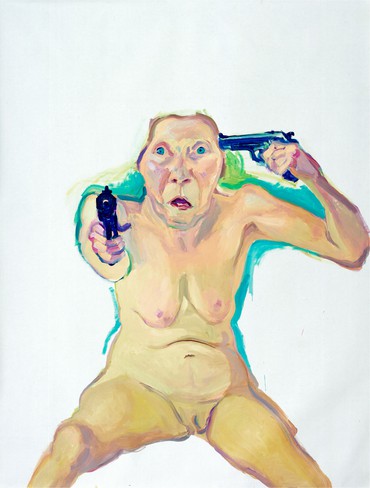

GBTo a large extent, I am very much more interested in the figure than I am the ground. It’s like the artist Maria Lassnig said: “I just want to paint the figure—that’s what interests me.” You see that to some extent in [Pablo] Picasso’s work as well—he’s not really interested in what goes on behind the figure: he’s just so intent on the figure itself. That’s why you don’t really see any Picasso landscape paintings.

And with Lassnig’s work, you have this wonderful sense that the figure could be transposed into any environment. They’re not made too specific; very often her figures are naked, so there’s nothing to place them in a particular time, which gives them a transmutable quality, in that they could be somebody you know.

So I was interested in that idea of not having a background, or having a ground that is very ambiguous: it’s either clouds or a very loosely formed landscape that could be anywhere. Or, as in this case, it’s stars, which are the epitome of the eternal.

JKAlthough they do also bring with them other, more pop sensibilities, and associations with the space age and sci-fi.

GBAnd twenty years ago, I was doing work that was very much based on science fiction, that idea of fantasy, of being lost in space, and of escapism. Why one person’s fantasy is often so similar to somebody else’s—that we have shared fantasies, shared escapisms.

I think the stars are a way of being in nature as well. I mean, there’s a very nonspecific sense of being lost in time and space.

JKYes, there is a timelessness, alongside those rich cultural associations: the possibility of space as a blank canvas, an endless, unknowable, edgeless universe.

GBI was listening to a program on the radio recently where people were talking about consciousness. One of the scientists said that consciousness is just a series of neurons and electrons hitting off each other in our brains and creating this sense of consciousness, and that we’re actually living in a universe which is constantly expanding into nothingness. It’s impossible to conceive of this, just as it’s impossible to conceive of our brains being just neurons. That’s why we create God: to try and cement all that back together and create meaning.

I thought, “That’s exactly how I feel! That we’re living in a universe which is constantly expanding into nothingness.” My brain feels exactly like it is electrical impulses and that’s all it is—but I don’t need God to fill in the gaps. I feel humbled by the universe and I don’t have any grander scheme for myself. I don’t need to invent a greater reasoning other than my brain is here now and it won’t be here forever. My paintings are here now and they won’t be here forever. I don’t need to feel the eternal—I like my lack of importance in the universe. And to some extent, that’s what the starry background is there for, to say that we’re not really very important. Human beings are very good at thinking of ourselves as being overly grand and our cultures as being more important than any other thing in the world, and they’re not. That’s why my feet are dead and floating in space. It’s a very grand thing to have lived a life. One of my works is called Life is Empty and Meaningless, and I think to some extent it sort of is—but I think that’s wonderful.

JKThis painting holds that intention, those contradictions between the specific and the universal, the time-bound and the timeless. And as with all of your work, there’s a sense of living and breathing, as if the surface is moving before our eyes. Your paintings aren’t fixed: they seem to move, shifting and slipping.

GBPart of what I’m trying to say with the brushstrokes and lines in the paintings and the drawings is that we are constantly in a state of flux, that we are made of atoms very loosely held together. Things travel between us—travel through us—all the time. We’re not solid objects. So I’m trying to create the sense that we’re fluid and we won’t be here in this form continuously; we’re always changing. We’re growing and decomposing at the same time. And that is a wonderful thing: to decompose elegantly.

JKThinking about brushstrokes, I’m interested in the flatness of your paintings. You play with the gestural mark making of some of the artists whose work you appropriate, but purposefully lose any sense of the encrusted, impastoed surface, flattening and in a way neutralizing the surface of your paintings. Has that changed at all in these newer works?

GBI haven’t become a modernist and I still aim to deceive the viewer, but the gesture—the original gesture—is more evident in these newer paintings than it is in the old ones. That one on the wall behind you, which is called The Real Thing, is from 2000, and the gesture there feels much more staid. Frank Auerbach’s original gesture is trapped on the other side of the picture plane there, whereas in the newer paintings, you’re seeing more Glenn Brown in them, and less Dürer or Auerbach. I’m allowing myself more “voice,” which just felt necessary in order to bring out the real me, which I felt was being a bit too coy and hidden for years.

JKHow would you define your “voice”? What is the “real” Glenn Brown?

GBMy paintings are very slowly made and built up over time. They take many months to paint, and there are elements hidden underneath that you don’t see, but that were very important nonetheless in the construction of the work, even if they’re hidden in the end by the final layers. The intricacies of it are very important: you’re meant to go up close and look at how the thing was made, and how it breaks down, to see the tiny little brushstrokes painted with a brush with just a few hairs on it.

I am cautious in the way I paint. I don’t make rash decisions. I like painters who make rash decisions—it’s why I like Maria Lassnig’s work so much, because she’s much more assertive and energetic and spontaneous. But I’m not. So I pretend to be, but really I am much more slow and cautious. I have to rehearse quite a lot before I do something. It’s like a swan that appears to be gracefully gliding along but its feet are swimming furiously underneath. I’m trying to show a bit of the flapping feet beneath, to show that the works are actually quite complex in the way they’re created.

JKWe touched on your method of using reproductions of other works of art as the jumping-off point for your paintings, how you’ve long engaged in the technologies of reproduction, and how you also use computer programs to help manipulate images before you move to the easel. That boundary where the physical and the digital meet, it seems to me, is getting more and more interesting with the advent of new technologies like 3-D printing, machine learning, AR, and VR. I wonder if these big leaps forward in the digital realm are in any way interesting to you, whether you see them as having possibilities for you, or not?

GBA friend of ours gave us an introduction to VR technology and painting—and it was fantastic. I mean, when you start using painting tools with a virtual reality headset on, it’s absolutely amazing. And yes, it will be very important to the visual arts—well, I hope it is, because it’s a very exciting way for painting and creativity and drawing to go.

JKDo you feel it’s something you might experiment with if the opportunity came up?

GBAbsolutely, yes. It was so enticing and my immediate thought was “Picasso would’ve loved this!” I say Picasso particularly because of his big gestural marks—because it feels at the moment that that’s what the technology is capable of. You’re quite aware that everything is a bit pixelated when you have a headset on, and therefore you have to make quite big gestures in order to overlook the fact that it’s all a bit glitchy. My work tends to be a bit more refined and delicate, and therefore it didn’t quite feel like the technology was there yet. But I do want to do things using virtual reality. The relationship with the audience is problematic at the moment, because not many people have headsets. When it becomes more normalized, that’s when great things will start to happen.

JKYou’re right that the technology isn’t there yet, but it’s certainly on its way. It’s interesting that the artists who’ve been dabbling with VR so far have been in the main performance and installation artists, or sculptors, where perhaps the connection to physical space feels more relevant. Though there are also exhibitions that have started to play with painting and tech, like Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, which has been touring around the world recently, where you get to walk “inside” a series of Van Gogh paintings.

GBWhen we were in the South of France in 2019, we saw a “Van Gogh experience” in some limestone caves, the Carrières de Lumières at Baux-de-Provence. They used a lot of powerful digital projectors to project manipulated images of Van Gogh’s paintings on the walls, ceiling, floor—everything on a vast scale. It was fantastically kitsch, but quite entertaining, and you could see that, given enough time and skill and learning, it could be a tool that works really well.

JKSkill is something that’s very important to you, isn’t it? That idea of learned craft and the hours—years—of labor it takes to become truly skilled at something. The sociologist Richard Sennett wrote about something similar in his book The Craftsman, arguing that dedicated commitment, striving to be excellent—whether in painting or cooking or computer programming—gives us deep pleasure and is part of what makes us human. What’s your feeling about your own level of skill as a painter? Does it excite you that you’ve gained in technical skill over the years, that your latest paintings achieve something new?

GBI spend my life feeling incredibly unskilled, because I’m always trying to do things that I can’t quite manage to do. And so I never congratulate myself on how skilled I am. It’s the absolute opposite, because technically I would love to achieve lots of things—get two colors to act in a particular way, borrow some composition from another artist, or use an edge in a way that I find interesting. It makes my life a continual nightmare to some extent, because I can never achieve what I really want to achieve. I get close sometimes, but it’s always a disappointment.

JKA lot of artists feel that, I’m sure. Perhaps it’s part of what makes one get up in the morning and keep trying.

GBOh, absolutely. Art is the most enjoyable disappointment I can think of.

All artwork by Glenn Brown © Glenn Brown