Somaya Critchlow lives and works in London. She obtained her BA in Fine Art Painting at the University of Brighton in 2016 before entering the Royal Drawing School, London, where she completed a postgraduate diploma in 2017. In October 2022, Critchlow will present her second solo exhibition with Maximilian William, London. Photo: Lewis Ronald

Katy Hessel is an art historian, broadcaster, and curator. She runs The Great Women Artists podcast and Instagram account and her book The Story of Art without Men is published in September (Penguin, 2022).

SOMAYA CRITCHLOWWhen you started curating, was it something you always wanted to do or did it happened organically?

KATY HESSELI’m not a curator by training, I’m more of an art historian. For me, the form of the group exhibition is most appealing, as it’s a place to experiment, to put different artists together and spark conversations. I’ve never orchestrated a solo show so I don’t know what that’s like, but with group shows you can really explore a theme, a subject, or a concept, grappling with its varieties and resonances.

From the time when I really began engaging with art, before university, it has been a dream to curate. That said, it took a while to make it a possibility. I worked in galleries and museums, and then, in 2017, I was able to stage my first exhibition: it was in the foyer of an advertising agency! I always tell people, Never be precious about where you first show or curate—everyone’s got to start somewhere.

SCIs it right that you started your Great Women Artists Instagram page when you were around eighteen—

KHI was twenty-one.

SCTwenty-one, okay. So you were working at the Victoria Miro gallery in London.

KHI worked at Victoria Miro throughout my whole time at university. And then, when I was twenty-one, I started working for a museum. It was straight after university that I started The Great Women Artists. It was very much inspired by Alice Neel.

SCAlice Neel captivated me as well. She was working hard throughout that period of Abstract Expressionism, and obviously she didn’t get recognition until much later. When that finally happened, she was like, I deserve this recognition, I’ve been doing this for years. I think it’s interesting to look beyond codified periods and movements in the art world, like Abstract Expressionism, and see what else was happening concurrently.

Since starting the Instagram page, do you feel your thoughts on the art world have expanded?

KHNot only have I grown up, but in those seven years—you and I are close in age, so I’m sure you’ve felt this as well—the art world too has completely changed. The world at large has changed: this was pre-Trump, pre-Brexit, prepandemic, pre-war in Ukraine. The gatekeepers have also changed dramatically. In 2016, Frances Morris became the director of Tate Modern—it was one of the first positions that really shifted—and she’s been instrumental in bringing women artists to the fore, curating Louise Bourgeois, Agnes Martin, and Yayoi Kusama exhibitions. To take these risks in an institution like Tate Modern, to say, I’m going to put these women at the forefront, is radical. Now the head of the National Gallery of Art in Washington is a woman; the head of the Louvre is a woman. It’s up to them to change this world.

My own position in the art world has greatly changed from being an assistant at the gallery to now being able to curate my own shows and write my own books and try to forge my understanding of what art could be. I’ve written this book, The Story of Art without Men, but I explicitly say that it isn’t definitive. I’m standing on the shoulders of all these people who have come before. This is a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the story of art. But what’s exciting is that all these stories are being discussed widely, and I think it’s such an exciting time to be in the art world.

What do you think? Since you graduated from the University of Brighton and from the Royal Drawing School, how has your view of the art world changed?

SCI came out of university feeling incredibly frustrated and confused, but not really knowing why. It was only during postgraduate study that I started to figure it out. I was back in London (whereas I had studied out of London initially) and heavily involved with visiting galleries and looking into art history through all these classes. There was a lot of talking about the same men, the same kind of canon and history of the art world. It made me realize where that frustration came from; it framed where things were then and how I felt. I can see how the art world has changed, but it’s weird because it seems to have coincided with a real personal journey for me. There’s so much in education that’s exciting, but I think to take it and make it work for you, instead of feeling alienated or excluded from it, is liberating.

What did you think when you were studying to be an art historian? How does that education tie into what you’re doing now and the changes that you think are occurring?

KHIt’s so fascinating because when I was at [University College London], we had this overview course in which we studied legendary figures in art history. I know it’s very different now—someone who works with me is currently at UCL—but when I did it, we didn’t look at any women. The worst thing was that it didn’t even occur to me that something was missing.

SCWhen did you eventually have that realization?

KHIn my final term there was this visiting teacher, Andrés David Montenegro Rosero, who taught an amazing course on activism in art. I’d had a very traditional art-historical education until then: I’d learned about the Surrealists, the Dadaists, the photojournalists, the Pop artists, et cetera, and they’d all been men. In this course on activism we suddenly learned about people like Ana Mendieta, and Land art, and what that meant. And the world shifted for me—I suddenly realized, Oh, okay, art can be a force of change. And yes, it might sound naive now when I look back at it, but I was a twenty-year-old and my world was turned upside down. Even just learning about Ana Mendieta and what she did, how she used the body, and how she talked about the world, migration, borders, memory, loss, death—it was mind-blowing. Did you have a turning point?

SCI had a classical technical training, but I didn’t know traditional art history so well. The bits I got were from family—Rembrandt and the National Gallery, you know. Because I went to a performing-arts school, we looked at loads of contemporary art, but I’ve always felt much more of an affinity with painting and the old masters. So I come at it from a really different point of view. I’m curious about the current drive in interest in minority and female artists in the art world, particularly in institutions, which I think feel this need to catch up. They’ve been putting on a lot more exhibitions by women. What are your thoughts on how this is being handled?

KHEverything is very much in flux. My first thought is, How has it taken this long? Feminists and activists like Faith Ringgold, Linda Nochlin, Alice Neel, and many others have been doing this work for a long time, but it still shocks me that institutions were able to avoid these conversations until so recently. Still to this day, I can’t believe there hasn’t been a Remedios Varo retrospective or a major Magdalene Odundo exhibition in London. How have we gotten to this point? As you said, there’s suddenly this scramble, and what I don’t want to happen is for the scramble to be a fleeting moment and for people to think that female artists are simply a trend, because they’re absolutely not. I spoke earlier about how Frances Morris has been putting on these amazing exhibitions at Tate Modern, but at the same time, are these institutions collecting these works? Because the most important thing is legacy, and I don’t want people in the future to look back to the early 2020s and say, Oh, that was such a progressive time. They said that about the ’70s and then the ’80s happened. I don’t want history to repeat itself and I’m in this for the long haul; hopefully I’m not going anywhere, so I want to create substantial interviews and books and resources that people can use. I’m just a speck in this; it takes a whole army, which so many people are part of.

SCI’m really excited about your new book, and I believe you’ve talked about the motivation for it coming from Ernst Gombrich’s Story of Art [1950]. I love this, because when I was studying, Gombrich was always on the reading list—it was this bible for artists. Yet looking back at it, it barely mentions any women. What’s going on with your book? It’s a big project, going from the 1500s all the way to the present. What were your hopes in putting this book together?

I was writing this book at a formative time in history, between 2018 and 2022, and this is my take on it. What I love about art is the fact that everyone is entitled to their own opinion and somebody can read something and disagree with me, and that’s great as well.

Katy Hessel

KHFirst, I have to say, I love Gombrich’s Story of Art. I grew up on it, I still reference it, and I love reading it. But it’s only representative of the old guard. What I hope is that my book is an additive. First of all, the title The Story of Art without Men makes people laugh—which I like, because I think humor’s a great way of getting people to be serious about something. And then suddenly you’re like, Oh, can I name ten female artists?, or, Did that art-history book I read when I was younger actually include any women? I hope it shifts people’s perspectives.

What I love about Gombrich’s writing in The Story of Art is that it’s readable, it’s enticing. He makes you think about so much, and that’s what I wanted to do with this book as well. The word “accessible” gets thrown around so much, but I really feel that this is a book for the twenty-first-century reader. It’s dense, but it’s, I hope, energetic and exciting.

For my podcast I interview some of the world’s most renowned academics, artists, and curators—these are highly intelligent people, and what I like to do is break things down a bit and stand in as the perspective of the listener. I tried to do the same with my book. And I’m genuinely in love with every single artist in the book. I could talk for hours about Rachel Ruysch or Cindy Sherman or Elizabeth Catlett or Loïs Mailou Jones. Art history isn’t offered at many schools, it’s not prioritized in the UK, or at least where I went to school. And for a kid to be able to find it in their library—I hope it invites them into something.

SCIt’s not that women are missing from art history entirely; obviously a few make it in. But a lot of women artists just haven’t gotten their due.

KHAbsolutely. This comes up a lot with marginalized artists working in different mediums, right? So I have a chapter on fiber arts in the 1960s. And when I think of work born out of war, especially World War II, I look at Lee Miller, as opposed to a male photojournalist, and think about what she had access to: just because she was so restricted, she told a completely new side of the war. Or, someone like—I’m sure you’re familiar with Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theater? [1941–43]? It’s the world’s most emotional and heart-wrenching piece of art, and somehow it makes what was happening human. This was a woman, similar age to me, who shared what she went through and what it was like for a Jewish girl to grow up in Berlin at the rise of Nazism. These artworks make these historical events real, in a way.

SCHow did you find putting the book together as a project? How long were you working on it?

KHIt’s been seven years in the making. I worked very intensely during lockdown, I shut myself off and worked straight. And I loved it. The book was meant to be 30,000 words and now I think it’s 100,000 words; every single artist led to something new. Honestly, it pained me to only write 150 words on Marisol or Augusta Savage, both of whom deserve so much more.

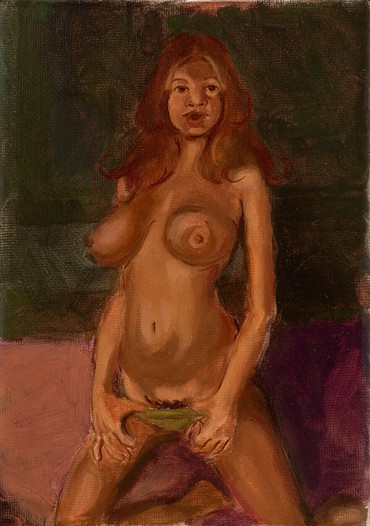

A lot of these artists are evolving, as you are. You’re at this exciting part of your career, and yes, I have a work by you in the book, from about 2019. That will be reflective of one particular moment in your career, but you might be working on something completely different in a decade, and that’s fine. These are ongoing careers, these are ongoing questions. I was writing this book at a formative time in history, between 2018 and 2022, and this is my take on it. What I love about art is the fact that everyone is entitled to their own opinion and somebody can read something and disagree with me, and that’s great as well.

SCHaving finished the book, what are you thinking about for the future?

KHI’m focusing on curating a few exhibitions. The book has sparked so many ideas for other projects and I think that’s what I want to be doing, to write more and curate more.

SCWhat authors have influenced you, in or outside of art?

KHMy favorite writers to read on art are actually nonart writers. Hilton Als, the theater critic for The New Yorker, I could read all day and all night. Deborah Levy, one of the greatest writers of our time. Ali Smith, the way she plays with words and art. I interview authors on my podcast—Olivia Laing, for example.

SCAre there any specific books that you hold close? I’ve continually returned for inspiration to Philip Guston’s essay “Faith, Hope and Impossibility” [1966].

KHIn addition to these writers I’ve mentioned, Eileen Myles’s poetry on Joan Mitchell enchanted me and gave me a totally different perspective. What I love about doing my podcast is that I can interview artists on the work of other artists. It’s not going to be by the book, because artists and writers have this imaginative approach.

SCYeah, you’re interacting with the work on so many creative levels.

KHI also invite interactions with the public, listeners or readers, because I want to know what they think. And people don’t have to know anything about art to enjoy it. It’s about a feeling, it’s about a reaction, and that’s the strongest thing for me.

Katy Hessel, The Story of Art without Men (London: Hutchinson Heinemann, 2022)