Ashley Overbeek is the director of strategic initiatives at Gagosian, where she has the pleasure of working with artists on Web3 and digital projects. Overbeek is also an advisory-board member of the Art and Antiquities Blockchain Consortium, a 501c3 nonprofit, and a guest speaker on the subject of art and blockchain technology at Stanford and Columbia University.

Andrei Pesic is a cultural and intellectual historian of early modern France, with special interests in the arts and economic thought.

Ashley OverbeekAndrei, thank you for taking the time to speak with me. You teach a class at Stanford called “Art and the Market,” which back when I was a student I took and loved. What was your impetus to start the class?

Andrei PesicMy desire to talk about art and the market, especially with Stanford students, was spurred by how dissatisfied I was with media coverage of the contemporary art market. It tended to trumpet or bemoan every event as an unprecedented innovation, and thus had a very narrow focus on the contemporary. So instead, I wanted to try to place the very real novelties in our time in the longer historical context of the ways that artworks have been valued and exchanged.

AOWhen did you first start hearing about NFTs?

APGosh, I’m a bit of a dinosaur. I’m a historian, so I’m never the first one to hear about something. I heard about NFTs right before the Beeple auction in the spring of 2021. I was able to add the topic to the syllabus immediately and I said to my students, There’s nothing academic to read about it but we can read the journalistic accounts, watch the auction video, and look at the Everydays project. And that produced such fantastic discussions among the students about the nature of value in art. It became this wonderful concrete example, one that really offended a lot of the students in an interesting way. I found myself being the defender of trying to understand NFTs on their own terms, whereas a lot of the twenty-year-olds were utterly outraged by it and thought it was really just a scam. And I thought that that was an interesting dynamic in itself.

AOOn scams, I think that’s such a common, immediate reaction when people hear about something going on in the crypto space. How have NFTs impacted the conversation around authenticity in the art world?

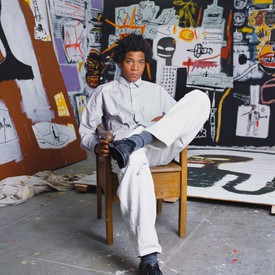

APThere are so many wonderful examples of forgeries and so much deep uncertainty about the attribution of a lot of artworks, especially from the past. Although, as we saw with the cardboard [Jean-Michel] Basquiat scandal, it can happen with artworks made during our lifetimes just as easily as with Vermeers. There has long been interest in what forgery shows about the social-trust and authority structures that undergird the whole art-historical complex that authenticates artworks.1 In a way, the NFT was undermining even the most basic version of that structure. The blockchain allows NFTs certainty of ownership and artist attribution, and yet there is radical uncertainty about their value.

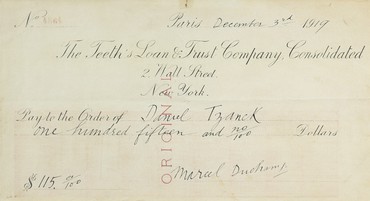

You can think of previous waves of outrage with conceptual artworks, for example Marcel Duchamp’s Tzanck Check (1919), in which a fake check became an artwork. The question of its authenticity as something that Duchamp created himself was certain, whereas its status as a check was obviously false. So we have lots of people who have played with this distinction of whether an individual object has value or not, but it’s really interesting to see a whole category of objects, NFTs, and the question of their value become such a lively topic for discussion.

AOI don’t think you can talk at length about NFTs without speaking about the merits of blockchain’s immutable record-keeping. But this technical solution—the ability to store an artwork’s proof of ownership and provenance information on a blockchain—hasn’t solved much regarding the larger concerns of NFTs’ value, worth, and scams in the art market. Some might argue that the role of a dealer is to help an artist navigate such a complicated environment, but the NFT community is often vocal in its advocacy of direct communication between artists and their collectors, without a gallery as an intermediary. What can the NFT space learn from historical dealer/artist relationships?

APIn a way, what’s funny and interesting about watching the early development of NFT marketplaces is that it’s almost like going back to the time before the dealer system really got going, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century. In my class we read two sociologists, Harrison and Cynthia White, who describe a transition from what they call a focus on canvases, individual artworks. For artists coming to display their work in the Paris Salon, you’re only as good as your last hit; you’re bringing new artworks to the market every year and trying to sell them as individual works.2 And what the dealers do, starting at the end of the eighteenth century and then even more so in the nineteenth century, is to instead bring this focus to the longer span of an artist’s career. So you go from canvases to careers. The dealer supports the artist from presumably an early point in their career, helps them develop, provides some sort of financial stability for them to make their work and to have the kind of freedom to not have to be constantly worried about producing work just to make ends meet the next month.

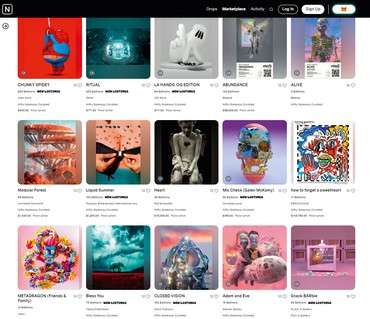

So what’s funny is that NFT marketplaces are providing more of a canvases model for now, where it’s an individual artwork that’s the object. Lots of artists, even famous artists with gallery representation, are selling NFTs, but the marketplaces themselves are structured on the level of the artwork. In a funny way, it kind of recreates the visual effect of the Paris Salons, where you had this enormous room in the Louvre covered in paintings and sculptures from floor to ceiling, creating an overwhelming visual spectacle where individual artworks kind of struggled to stand out from this tapestry of other ones surrounding them. That’s very much the NFT marketplace aesthetic, as compared to the modern gallery, where a single-artist show is the gold standard for display. History is not exactly repeating itself—the decentralized NFT marketplace is the opposite of the Paris Salon’s curation by an academy—but the cutting out of the middleman, of the dealer, raises some of the same questions that were raised in the past when you had artists selling their work directly into the marketplace.

AOIn the canvases model of the Paris Salons, were the public attendees also purchasing work? I ask because this discussion makes me think about all the ways in which we assign value to NFTs. In a lot of conversations that I’ve had, people say the best NFTs are the ones that sold for the most. The sale price is almost like an adjective describing the artwork or the artist’s value. So I’m curious: who were at the Salons, and were they mostly looking, or were they buying? How does that differ from what we’re seeing today, when almost everything in the NFT space comes attached with its sale price?

APIn the Salons, you could go in for free if you were decently dressed. That was a rare kind of mixing of social classes in old-regime Paris. There are many historical descriptions focused on the very heterogeneous audience, countesses next to fishwives—that’s the kind of joke the writers of the time would make.

In terms of whether the public was also purchasing, it’s, again, very mixed. It’s known that all of the collectors would show up at the Salon to see what was going on, but tens of thousands of people would come over the course of the run, a month, and very few of them could afford to or were interested in purchasing artworks. So a lot of the academicians were offended by the idea that anyone could come in and pronounce judgment, or that an art critic who couldn’t paint a painting well him- or herself would dare to pronounce on the artists’ talent or the paintings they’d produced that year.

The idea that the most expensive artwork is the best one is something that eighteenth-century critics would see as just utterly false. Back then, the most expensive work could just be a portrait of a very rich patron. In the case of the Salon, the public goes in and says, you know, What’s this ridiculous portrait of this fat guy in a wig? Who is he, who does he think he is? And it obviously horrifies the artist to hear that kind of thing because portraits are such a big part of their practice, and yet that type of painting sits badly in this big Salon space. A Salon is just not the ideal condition to see portraits of individuals, especially when the public doesn’t know who they are and can’t figure out who they’re supposed to be.3

AOThis conversation has gotten me to start thinking about ownership. A lot of the appeal of NFTs is the idea that you can take something that’s digital, and therefore infinitely reproducible, and make it ownable and scarce. Historically, possession and ownership of art have been important. And then you have the Salons, where people are getting to interact with an artwork without owning it, and there’s value in that kind of dynamic relationship between viewer and art. Likewise in a museum, where attendees may go and experience art but they don’t own it. How has ownership, or the premium that people place on owning art versus viewing it, changed over time?

APGreat question. I don’t think there’s a very clear progression from one to the other. I think it’s absolutely clear that the public display of artworks really changes in museums: they changed the extent to which people can potentially have a relationship with an artwork even if they don’t own it, right? I’m thinking of the great Thomas Bernhard novel Old Masters: A Comedy (1985), where the protagonist goes and sits in front of the same paintings in the Vienna Kunsthistoriches Museum every day and has a strange quasi-proprietary relationship with these paintings, even though he doesn’t own them, and spends much of his time yelling at people for not appreciating them.4

Conversely, I can think of ways in which collections, and what it meant to have a collection, really changed in art history. In eighteenth-century Italy, the idea was that you were creating a collection that would stay in your family’s palazzo, hung in the same way with the same works over hundreds of years. There was a different model for collecting in France, where art collectors would put together a compilation, sometimes among the best collections of paintings, and then sell it all at once at auction. They’d say, I’m not interested in Dutch seventeenth-century work anymore, I’d like now to collect something else. I’m going to get rid of this collection, I’m going to make a new one. And it was much more a relationship—almost an intellectual relationship—that would be memorialized in a book. You’d print a book illustrating your collection, saying this was what it looked like at that moment. That collection doesn’t exist anymore, they’re all in different places. It was like temporarily bringing together objects that would then lead other lives somewhere else.5 So even in art history, you can think of all these different ways in which people have understood ownership.

On the other hand, there is a long history of special relationships between collectors and the objects in their possession. You can think of the very different model in Chinese art, where some collectors would put their seals on the borders of a painting and write texts that would then be attached to it. The collector would become a part of the history of the artwork that would then be passed down with the painting itself.

So it’s clear that a deep engagement with an artwork can happen exactly because you own it, because you live with it, because you spend time with it. NFTs again provide such a perfect test case for allowing us to disaggregate different parts of this mindset in saying that there may be a deep kind of connection that a collector can have by owning an NFT that they couldn’t have if they were just looking at it in some other digital context. Also, the choice to spend money on it, to collect, to bring it into your collection, forces the question of aesthetic judgment in a way that walking through a museum doesn’t because you don’t have to say, I’ll take it, or, I don’t want it. In the museum you can have much more of a disinterested regard. That moment of choice in collecting has interesting effects on the kind of aesthetic judgments that you make.

AOSo does ownership matter in the case of crypto art?

APWith digital/crypto artworks, there is a radical possibility for ownership not mattering, so it will be really interesting to see if it still does matter. And it does seem, to some people at least, that ownership continues to matter. It’s almost like a philosopher invented the NFT to pose this kind of question about human nature—whether we would still care about the ownership of something even if we could still enjoy it without owning it. I think that in the end, if there’s a good reason to own NFTs beyond some potential financial return, it will be something along the lines of the act of judgment that acquiring an NFT will show, and the kind of collection that you can create in putting certain works in dialogue with each other. Maybe there’s still meaning in this exercise of investing in a certain number of artworks and bringing them into your home, whether they’re digital or physical, and that act provides a different kind of experience with artworks and a depth of interaction with them that is rarely realized without the concept of ownership.

1See Bernhard Lahire, This Is Not Just a Painting: An Inquiry into Art, Domination, Magic and the Sacred, trans. Helen Morrison (Cambridge: Polity, 2019).

2See Harrison White and Cynthia White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

3See Thomas Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).

4Thomas Bernhard, Old Masters: A Comedy, trans. Ewald Osers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

5See Patrick Michel, Peinture et Plaisir. Les Goûts picturaux des collectionneurs parisiens au XVIIIe siècle (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2011).