Nalo Hopkinson was born in Jamaica in 1960. Her first published short story, “A Habit of Waste,” appeared in 1995 in the Canadian feminist journal A Room of One’s Own. In 1997 she received the Warner Aspect First Novel Contest, leading to the publication of her novel Brown Girl in the Ring the following year. She has published six novels, numerous short stories, and comics in DC’s “Sandman” universe.

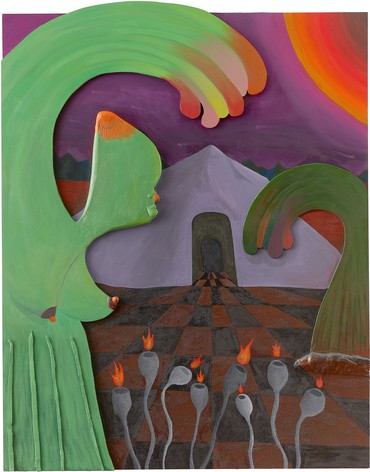

Alexandria Smith is a mixed-media visual artist based in London and New York. Her work interweaves memory, autobiography, and history to explore the complexities of Black identity and its relationship to the body. Photo: © Amoroso Films

Alexandria SmithNalo, I’m so excited to speak with you. I’ve been reading your books since college—Brown Girl in the Ring [1998] and The Salt Roads [2003] are over there on my bookshelf. They’re old copies [laughs], they’re in my permanent stack: Toni Morrison, you, Gabriel García Márquez, Octavia Butler, and Samuel Delaney.

Nalo HopkinsonThank you, Alexandria. I’m delighted to be in such great company—Delaney is one of my go-tos, for sure.

ASWhat drew me to your work was your rich, clever use of language and these spins you’ve made on folklore, in Skin Folk [2001] especially.

NHMy dad was a well-known poet in his generation in the Caribbean, and my mom worked in libraries. So I think the bent to wordplay happened early on.

ASYou were surrounded by words!

NHAnd people doing things with them. I mean, Caribbean writers can make a sentence dance for its supper [laughs].

ASI don’t have that, as a writer [laughs], but I hope I do that with my visual work.

NHIt’s there. It’s there. Looking at your work, part of what’s intrigued me is what’s buried in the titles. Like Backbend, part of the Ibeji series —that’s a clever use of language.

ASOh, that’s good to hear!

NHThat particular one intrigued me—apart from the character being an Ibeji, it looks like one of them has an injured arm.

ASOr never had an arm. I tried to play with expectations, thinking through our own reality and the reality of the world these characters exist in. Sometimes people think they’re missing limbs, but for me, they’re whole. They’re full beings with the limbs that they “have” or “do not have,” you know? I use air quotes because it’s perception, right?

NHYeah.

ASI’m trying to push that a bit. It’s easier to do now because I’m using a lot of color, whereas before, when the characters had skin tones that were similar to ours, another layer of complexity was projected onto the figures. But now that they’re multicolored, I hope they resist that kind of read [laughs]. But who knows?

NHI like that. I spent two years recently working on a comic series for DC. The main character was the deity Erzulie and I opened the comic with a huge party she was throwing on a large riverboat. I wanted there to be a ball competition in the middle of it and I wanted one of the competitors to have one and a half legs. I told the artist, you know, “I want the crutches to go flying, I want this person to be in the most dynamic position you can imagine, because they’re not limited. They have the body they have.” And he did an amazing job. This person is doing a somersault and just flying through the air, and that’s the feeling I wanted—that’s their body and they do what they do with it to the utmost and it’s not a question of, Oh, he’s missing . . . he’s got lots.

ASThere’s this interesting play with duality too, in that. It’s the lack versus abundance that I think a lot about. I’m thinking more about body as material, body as a space. In this new work I’m trying to depict the body as a utopic space, not just in a utopic space. There’s the motif of the island landscape, which is what you tend to think of as Utopia, this warm climate surrounded by water and sun. But in these newer works, the figures are becoming that space. They’re inhabiting and taking on these architectural or geologic poses. That’s why using wood, and assembling and collaging, became so key to the work: I didn’t feel like the bodies could just exist in paint. They needed to infiltrate our space, too, by coming out of the rectangle a bit.

NHI like that. I think we experience text through the body as well. When I’m writing fiction, I’m not trying to just get to your eyes or ears, I want the reader to be experiencing it from the body out. Metaphor does that most strongly, because readers have to map their own experience onto it. I’m constantly trying to find ways to pull readers in so that they’re living through the story while they’re reading it, rather than just watching it happen at a distance. I find lots of people use camera metaphors to teach writing, and I’m like, No, no, you are the camera [laughs]. It’s not this thing you’re carrying around, you know, putting on a subject.

ASOh, that’s really interesting. I think we came from a different educational style from what students now are used to—the way we learned our craft was by experiencing. That happens less with the younger generation; they try to plan and prepare everything in advance, to the point where they’re afraid to learn by allowing chance or failure.

NHStudents say to me, “So what do you want me to do in order to get an A?” and I’m like, “I don’t know.”

ASThat question [sighs]—

NH[laughs] You realize this is a creative pursuit? So what I’ve started doing is talking about the writing they do in the class as experiments. I don’t know what perfection is, and I don’t necessarily want to see it. I want to see you throw everything out there and make a hot mess and see what you discover from that. And it helps remind me I should do that too [laughs].

ASI always tell my students that I’m a facilitator—I have a level of experience that you don’t have, but at the end of the day, this is a collaborative endeavor.

NHI was talking to a group of Black high school students from the Vancouver area and they asked me if I ever feel impostor syndrome. I said, Well, not about writing. But about teaching—Oof, baby. Because it’s not my training, I still walk into a classroom and feel like I’m fumbling around, because I am [laughs].

I think we’re both so immersed in our work, and trust ourselves, and trust our intuition, that we pull in material from the outside world and situate it within.

Alexandria Smith

AS[laughs] I feel it too. I feel it in the classroom, as well as in art-institutional spaces. I know I’ve worked my ass off, I know I belong here, but I also don’t feel like I belong here. But I don’t feel that in the studio.

NHI notice the only people who feel impostor syndrome are people who are actually doing the work.

ASOh yes [laughter].

NHSo they’re already not impostors. But something is telling us, you know, we’re not good enough, we’re not something enough.

And you’re right about institutional spaces; it was a few years into being full-time in academia before I realized just how nastily competitive it is, like how it sets scholars against each other and is forever implying that they’re not good enough, so you get this weird competition/fear thing happening.

ASSpeaking of space, do you think there’s a difference between place and space? How do you think through these terms in your work?

NHI’m immediately flashing on Sun Ra, Space Is the Place [1972] [laughs].

ASOh yeah [laughter].

NHI think I have an answer to that, but Alexandria, you’re working in physical space in a literal sense with your work. Maybe you could speak to that question first?

ASIt’s tricky. To me, space is more spiritual, metaphysical, emotional, and place is an actual locale. But I think in my work I’m playing with ambiguous places, and how they interact with liminal and fluxus spaces, playing with those two and separating them. Sometimes those emotive spaces take you to a place, or reference a place. They can transport you.

NHI might tend to use them interchangeably, but would do so differently in each instance of using them [laughter]. What I can say, I’m very much about intentional community, about people coming together and building their own support networks, both emotionally and in physical space. So that shows up a lot as taking place in a space, to make room for yourself and others like you.

I’m from the Caribbean, so I think a lot about ocean-level rise and was actually talking to a Jamaican marine biologist who said, You know, it’s going to be much worse than we think, because people are talking about it in terms of an incremental rise when, in fact, it’s exponential. So I have a community living on the water in what used to be the Caribbean Sea, and as I think through it, it’s not so much taking back the space but remaking it, and remaking it in a way that acknowledges the actual geography—that there’s this changed place, but it’s still theirs. Humanity played a part in ruining it, and humanity can play a part in both survival and in undoing some of the damage. I talk a lot about place-making but it’s also space-making, because I’m usually talking about marginalized groups of people. There’s that sense that I need to elbow up some room.

Can I ask you a technical question? Typically, how do you begin a new project or work of art?

ASIt’s always a drawing for me. I don’t put brush to panel or canvas without having a drawing. The drawings are my safe space, and they aren’t made as blueprints for the paintings in any explicit manner. They’re independent, they have their own power, but then when I’m looking at them, it may sound corny but I let the work tell me whether it needs to also exist in another medium. There are some drawings I’ve never made into paintings and then others that I’m like, Yes, this is definitely going to be a painting. Because I’m excited about being able to move this paint around and fully engage with the materiality of paint to see what can come from this composition that the drawing has provided.

NHThat’s cool. I’ve been looking at your drawings, and for me, without the training, putting pencil to paper, I’m shaking [laughter], literally shaking. And you know, when I started trying to do that, it was at a time in my life where I was about to go homeless. So when I bought paper and pencil, I didn’t want to waste it. I look at your drawings and I see freedom and experimentation. What you do with line and shading and color, so that they aesthetically stand on their own, is very liberating for me. Because it’s so difficult for me to look at my own work when I try to do that and see anything useful in it.

ASOh, interesting. How do you start?

NHIt varies. When I was writing mostly short stories, it would often start with the title. It’s difficult to know what it is that my mind is approaching, but a title has this power of encapsulation.

I collect snippets, I call them my “ideas file,” but if I write something down as an “idea,” it’s usually pretty static and I don’t do anything with it. Usually it’s stuff I overhear, often wrongly, but what I’ve heard tends to be more interesting than what they said [laughter]. So I keep that file, and I will look for two things in it that seem to not have anything to do with each other, and push them together and see what happens. Because I’m not so good at plot. I have to really work at plot.

ASReally?

NHI have to scare plot up out of the story.

ASWow.

NHBut all the questions about “how do you work,” I always feel like I’m lying [laughs].

ASWell, what’s the real answer then [laughs]?

NHThat’s the thing, I don’t know. I fumble around until something happens. Sometimes it’s deadline pressure that pushes your brain into that space of desperation where creativity can happen.

ASYes!

NHI’ve had to learn to make peace with the brain I have. I’ve got ADHD, I’ve got nonverbal learning disorder, I’ve got fibromyalgia—a bunch of things that convene around organization and decision-making and memory. I was diagnosed fairly late in life, in my forties, so I’d been fighting my brain all this while, thinking there was something wrong with me, I’m not doing it right, I’m lazy, you know, and then realizing there was nothing wrong with me, it’s just the way my brain is wired. So I have to talk to my brain when it’s fighting doing something. I say, “So you know you want to do this thing,” it says, “Yeah.” I say, “All right, so what do you want to do now?” “Go watch bad TV.” “Okay, so let’s do that and you let me know when you’re ready to open the file.” “Okay, maybe” [laughs].

ASWow.

NHAnd I find that’s way more likely to work than me calling it a “block.” Often, if I’m in the middle of the piece, the block is really my hindbrain saying, You’re going down a route that’s not working.

ASAh. That’s a good way of looking at it. I’ll have to start shifting my perspective toward that as well.

I find that every time I finish a new body of work and I’m ready to start something else, I always forget how to paint. It’s just the most crippling, debilitating feeling, and I’m like, Wait, you’re, what, almost forty-one now, right [laughs], and you didn’t forget how to paint. It never happens in drawing, it’s painting only. It’s weird, and I don’t know if I’ve figured out a solution—because it happens every single time, for as long as I can remember.

NHThat’s the kind of thing I would decide is part of the process.

ASYeah [laughter].

NHIt’s like going through labor. We’re not at the part where we’re going to push yet.

ASOh, that’s so true.

NHAnd if you make it part of the process, then you think, Okay, this is where I am and then there will be another part of the process. I’m that way a bit about novels, which are really hard.

ASDo you prefer short stories over novels, then?

NHI can’t tell anymore. I used to prefer short stories because my brain could encompass the whole of it. I mean, a novel is like a country [laughter]. But once I started being able to perceive form in a text, then the length of the story doesn’t matter so much, except that [laughs] novels are really hard to get to the end of. But to go back to art and the body, and how you explicate the body in art, there are ways in which it becomes helpful that you’re getting older.

AS[laughs] How so? Enlighten me, please.

NHParticularly in fiction, and in the type of speculative fiction I write, the go-to body is the superhero body. You know, it’s perfectly symmetrical, it’s perfectly powerful, it’s young, it’s slim. And I can’t write that anymore, especially not now, as I’m writing through the body myself and I think about something like throwing a basketball into a hoop, this shoulder’s like, “No you don’t [laughs], you’ve got to use the other hand.” So you remember that bodies have particularities, bodies have uniquenesses. They each have their own language. I write so much through the body and it’s easier for me now to remember that everybody’s body is different and to celebrate that as much as I can.

Even things like putting on weight—I mean, my main character for the comics, Erzulie, is sometimes a mermaid, and I wanted an artist who could draw a thick Black woman who was strong and powerful and sexy. Because I kind of think that a skinny mermaid is a chilly mermaid [laughter]. So I wanted somebody who could represent that beauty and gravitas, and it was lovely to be able to describe how I wanted her to move, how I wanted her to look, and to have to remind myself constantly, No, her body’s more like yours than, you know, Supergirl’s [laughs].

ASI definitely do the same thing. It’s funny, my mom even said, That looks like my body in The Intuitionists, and I was like, “Oh, yeah. I guess it is your body” [laughter].

NHOh, of course. And that’s such a great title.

ASThank you. I mean, my titles are borrowed—stolen—the same way you accumulate snippets. I have running lists in my notebook, and in the Notes section of my phone, where I write down things that I read, titles from books. I mean, one of my paintings is called Skin Folk, like your story collection.

NHThat’s lovely.

ASI was drawing from the title of your collection, but also thinking about “All skin folk ain’t kinfolk,” right? So it’s also these very Black colloquialisms that I’m drawing from, too, where I’m chopping them up and remixing them.

NHThat’s where I got it from. Not being American, it wasn’t a saying I’d grown up with, so when I discovered it, I was like, “That’s nice” [laughs].

ASIt’s so perfect.

NHThat’s so cool that stuff echoes and recapitulates and remixes.

ASSpeaking of this, I have to say that I have a real love/hate relationship with change. I’m always moving because I like change, but change is also a coping mechanism for me. I’m always moving past something, and sometimes I think I move past it or through it a little bit too quickly; I don’t necessarily fully explore myself being in a space, or the work existing in this style of making. But I also trust myself, and I know that part of it is because it wasn’t doing exactly what I needed it to do. Moving from the Duality series and the Ibeji series to this new body of work, my goal was to make work that looked like my collage installations and my paintings had a baby. So I returned to canvas—I’d been working on wood—and the canvases were large, because I love collage installations where my whole body was engaged in the making and I would throw out my back [laughs] from how physically involved the work was, you know? So I think change is important, but I’m also hyperaware of it, and I almost overanalyze it to make sure that it’s supposed to happen, to make sure that it’s me being true to myself and not me running away from something.

NHThat sparks, because with my impatient brain [laughter], I do have the problem of not going deep enough into a practice or an idea before I want to be doing the next thing. I mean, I’m working in a time-based medium. Change has to happen in a story. There’s always that moment when you go, Okay, something has to happen [laughs].

ASIt’s interesting to think about what it means to be contemporary and how that figures into speculative fiction or utopian thinking or disregard for traditional temporal relationships. How do you keep it contemporary in addressing the present moment, if you need to at all?

NHDo you find there’s a way in which people, because we’re Black, are forever trying to throw us back into the past?

ASOh yes, I totally do. Especially making figurative work, I feel I’m fighting this upward battle throughout my career. I think part of it is that it doesn’t look like a lot of what’s out there. I’m not making portraits of other Black people doing leisurely things, you know—they’re not realistic depictions of Black or brown people, they’re sort of futuristic, surrealist. And I don’t think there’s been much space allowed for Black people, especially Black women, Black queer women, to exist in that space, to make that work. I can name some, but I didn’t know about them until much later. And I think that’s part of it too. It’s like when you start using the body in your work, people only see the body you inhabit and look at the work through that lens and place this expectation or projection onto you and the work. Do you feel that happens in your field as well, in your career, that you’ve sort of had to—

NHYeah. It’s happening less as the field educates itself more, but it still happens. And often it’s when people want to use it as a way of saying that my work is lacking. They don’t want to analyze it in terms of where and what it is, they’re like, Oh, well, it’s not like, you know, Black literature. Well, clearly it is, because I made it [laughter].

ASYeah [laughs]. To the contemporary question, it’s like, yeah, we’re definitely contemporary, but I think it’s automatic—there’s no effort that has to be made. I think we’re both so immersed in our work, and trust ourselves, and trust our intuition, that we pull in material from the outside world and situate it within.

NHAnd just temporally, what else would we be? We’re contemporary.

ASYeah. We’re not going anywhere.

Artwork © Alexandria Smith