Fiona Duncan is a Canadian-American author and organizer and the founder of the social literary practice Hard to Read. Duncan’s debut novel, Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull Press), won a 2020 Lambda Award. She is currently developing a narrative biography and critical study of the transdisciplinary American artist Pippa Garner.

The copy of Arthur C. Danto’s Playing with the Edge: The Photographic Achievement of Robert Mapplethorpe I was reading came from the New York Public Library. Published in 1996 following a moral panic about a publicly funded Mapplethorpe show, Danto’s survey is preoccupied with this context; he’s building a case for the work as art in defense against conservative (homophobic) accusations of child pornography and obscenity. What I was looking for was any information about the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, Mapplethorpe’s collaborator and the subject of his first art book, from 1983. With no index to shorten my search, I started reading cover to cover. By page 111, I still hadn’t found Lyon but I did notice something: a faint gray rectangle crossing fourteen lines of text across the page from Mapplethorpe’s gorgeous photograph of a man in a three-piece suit with his cock out. I kept reading. A few spreads later the same rectangle appeared, this time darker. I flipped the page and there it was again, darker still. One more turn of the page and the rectangle became a scratch on the surface of the paper. The page after held my answer: the same jagged rectangle was now completely cut out, severing this line at the bottom:

. . . men were, with perhaps t-- ---eption of Lisa Lyon, a woman who played. . . .

I turned the page and gasped. Within a photograph showing a square of rippling water was a coffinlike cavity where, I realized, a body should be. Lisa Lyon, the image caption read, 1980.

The only reason I’d taken this book out from the library was to find Lyon, so to find her missing—well, it didn’t surprise me.

Lisa Lyon, a bodybuilding pioneer and muse to Robert Mapplethorpe, died on September 8, 2023, in Westlake, California, at the age of seventy from cancer or stomach cancer. Lyon first came to minor or demi-celebrity in 1979 after winning the first Women’s World Pro Bodybuilding Championship. Five foot three or four and 105 pounds at the time, she was photographed lifting Arnold Schwarzenegger on her shoulders. Of Lyon, Schwarzenegger said: “She’s the best, I adore her.” Lyon posed for Playboy in 1980. That same year, she met Robert Mapplethorpe. They would go on to collaborate, or he took dozens/hundreds of photographs of her, or she posed for him. His or their photographs came together as a book, Lady: Lisa Lyon (1983). She was also photographed by Helmut Newton, Marcus Leatherdale, and Marcia Resnick. Lyon saw herself as a performance artist or artist. She challenged ideals of femininity. Her physique inspired Frank Miller’s depiction of Elektra, a Marvel Comics assassin. In 2000, she was inducted into the International Fitness and Bodybuilding Federal Hall of Fame.

That, roughly, is how almost all of Lyon’s obituaries read. Two longer ones in the New York Times and the Washington Post came closer to doing her justice, quoting her on her childhood (“dark”), on what women’s bodybuilding represented (“an image of strength and survival”), on what she wanted to look like (“a sleek, feline animal”), and on the ultimate compliment (“if someone asked, ‘What planet did she come from?’”).

From an obit of a public figure, though, one would hope to branch, to find more. But online, Lyon, with her plucked dawn-of-Hollywood eyebrows, is like a silent movie star.

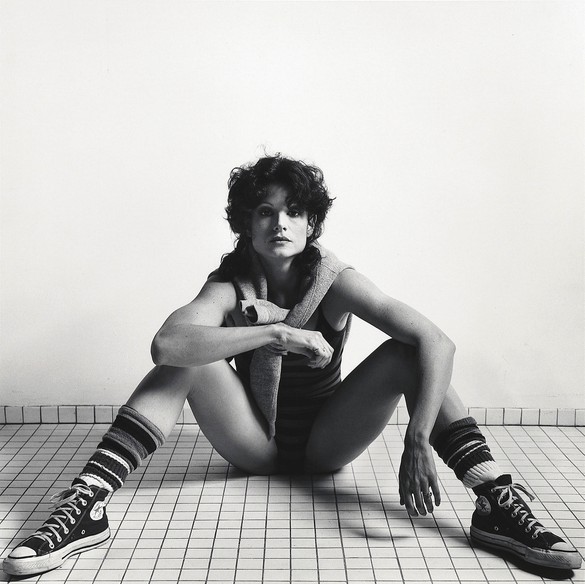

In photographs she is portrayed in black and white when she is not wearing red or, once, blue. It is 1979 to 1983 and she is flexing in a gym, on stage, at the beach, or in an artist’s studio. There is a harmony between her face and body, both being chiseled and supple. Her broad shoulders are to her narrow waist what her jaw is to her nose, while the dimple in her chin recalls the ridges of her abs. Her breasts and lips are pillowy, as is her hair—her curls could fill a pillow. As for her arms: whether lifted in victory pose, archer pose, or bicep pose, framing her hips in a battle stance, forearm at her waist in side chest pose, lifting dumbbells, or supporting her own body weight as she leans in a Grecian dress, Lisa Lyon’s arms are a knockout.

I had once heard and once read that Lyon was intelligent, “a genius” even. This was easy for me to believe because those who innovate—she inaugurated women’s bodybuilding and a new aesthetic for women—rarely do so by accident. The first people to do anything usually come to that thing through a Rube Goldberg–machine-type sequence of life events and intelligent reactions to them. They have theories and reasons that redirect the movement of things, charting a new course of events for themself, leading into new possibilities and sometimes a new standard for others.

What did it mean to Lyon to be an artist? What was “dark” about her childhood and how did that inform her? Did she have cats or did she just perceive herself to be one? And what happened? Why did she disappear from the public eye—her last press appearance was in 1991—after being so embraced by it?

About a year ago, I had a friend and former private investigator look Lyon up in her detective databases. She found some things of use but only out-of-date addresses for the woman herself. Then Lyon died and it was too late. She couldn’t answer my questions. Neither could the Internet. So I turned to the old Internet: people and printed matter.

Leonard Koren, creator of the California-cool Wet magazine—which was published from 1976 to 1981, a similar timeframe to Lyon’s fame, and which featured her in its July/August 1979 “Outlaws” issue (with cover star Debbie Harry)—said that he and Lyon came from the same “milieu, middle class West Los Angeles.” She was “a petite intellectual girl” whose conscious practice of building her body could be considered “conceptual,” and “like a conceptual artist, maybe she didn’t have a lot to show for it” in the end (I had asked about her legacy). In her Q&A with Wet, Lyon responded to a question about her legacy, stating, “I’d like to be a proponent of social change and a representative of a new artistic standard.” Will that be through bodybuilding? She wasn’t sure. Bodybuilding “doesn’t have this ultimate kind of importance attached to it,” she admitted, “it’s a kind of a low-life thing to do,” and “that makes it almost ridiculous to talk of it as ultimate achievement or pure art.” But she liked the “humor” of the practice and beyond the “inane side,” she said, there was “the serious side.”

That same year, 1979—the year Lyon put both women’s bodybuilding and herself on the map by winning the first ever formal women’s bodybuilding competition—Eve Babitz profiled her for Esquire. “Lisa and I know all the same people in the movie business and the art world and even in jazz,” Babitz reported, using Lyon’s first name because they knew each other as well. On the record with Eve, Lisa explains that she started bodybuilding in 1977 after meeting Schwarzenegger; before then, she had “studied dance and kendo—that’s Japanese fencing—” and before that she had been an art student pursuing medical illustration. Of Lisa’s student days, Babitz recalls that “she was very political and studied criticism in [UCLA’s] graduate film school, which, as everyone knows, is where in L.A. Karl Marx resides, at least in spirit.” Lyon’s father, we learn, was an oral surgeon, her mother an interior designer. Eve shadows her from the floor of the original Venice Beach Gold’s Gym—then the mecca of bodybuilding, where no women practiced, reportedly, until Lyon broke the seal—to its changing room and then to lunch, over which Lisa tells Eve that, thanks to bodybuilding, “I’m happy all the time.” She flexes her phallic arms and states, “It’s art. It’s living sculpture.”

Lyon would push this idea further. Her 1980 debut in Artforum—a portfolio of photos of her by Mapplethorpe—introduced her as “a performance artist.” And she did perform. Painter Nancy Reese recalls seeing Lyon perform naked and covered in graphite circa 1979–80 in Venice, California: “She used sand and stones,” Reese remembers, “like the ones in the Kyoto temple gardens as her stage set. The audience was rapt, mesmerized, as she slowly and powerfully moved around the small stage assuming various archaic poses. It was like seeing some sort of zen version of Nijinsky dancing in Afternoon of a Faun. I can’t recall if there was music or total silence. The performance seems to me now not as an actual event but the memory of a dream.”

This performance was not, as far as I could discover, documented. One can find photographs of another performance from 1979–80 at the University of California, Irvine. On the website of the artist Susan Kaiser Vogel, the work is attributed to her. “Peach pastel blocks, lead bricks, drawings on paper, human body, graphite, sound,” reads Vogel’s materials list. The body belonged to Lyon, who had herself painted in graphite again (it was her thing). The work, titled Point Conception, Lead Barrier Reef and Leadwall/Wishing Well, involved Lyon posing in front of a peach brick-wall, performing a similar sequence of flexes as she had in her 1979 International Federation of Bodybuilding winning debut.

The conceptual artist Pippa Garner, known until 1992 as Philip Garner, happened to go to that competition, “an obscure fringy event,” as her ex-wife, the Reese from above, remembers it, “in rat-infested Skid Row.” An amateur bodybuilder themself, Garner came home totally wowed by Lyon’s androgynous power: “she was definitely,” Garner says, “an avant-garde artist.” Inspired by Lyon and Chris Burden, Terence McKenna, and the Plasmatics’ Wendy O. Williams, Garner started gender-hacking in 1986. Like Lyon, she positioned the willful transformation of her body as art. This was dismissed by her peers in the LA art world as a lark taken too far. Little did they know, a generation who would embrace Garner’s prophetic genius was just being born. Once introduced, will they love Lyon as well?

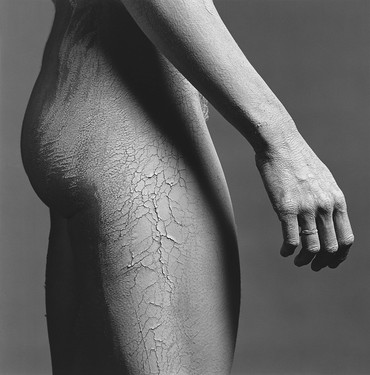

Garner wasn’t the only androgyne inspired by Lyon. Author Kathy Acker briefly trained with her during her celebrity heyday. Acker kept the practice up and in 1993 published a brilliant essay on bodybuilding, “Against Ordinary Language: The Language of the Body,” in which she heralded the practice as “about nothing but failure.” Because you lift until you can no longer, that’s how muscles grow. You tear your muscles by pushing yourself just past the point where you want to quit, then you quit, and it’s then, while repairing, that your muscles grow. They grow so that next time they can meet your challenge. For Acker, bodybuilding was a quadruple fail because it was impossible to relate in words and because it brought one in contact with the body, which decays and dies, so you’re working against language, physics, time, and the West’s fear of death.

I wonder if Lyon ever came to a similar conclusion. Her writing on bodybuilding in her commercial self-help guide Lisa Lyon’s Body Magic (1981) talks more about success than about failure, although that may be the genre speaking. Body Magic boasts about “the spiral of success” wherein mind, body, and spirit are connected, not unlike the chakra system. Everything in your life, the book promises, will benefit from physical movement.

One look at Lyon’s 1979 winning competition performance and it’s obvious how important movement was to her practice. She moves with the grace of a cat, a dancer, a tai chi master. Joel Fletcher, a Hollywood animator, happened to film her 1979 stage act on his Super 8 camera. He was at the back, though, and it wasn’t until computer tools allowed him, in 2013, to stabilize his shaky handheld footage that Lyon’s debut became accessible.1 In this footage Lyon looks supernatural, like an animated cartoon come to life. But remember, she studied anatomy, martial arts, and art itself, not to mention show business—she was from Los Angeles. She wasn’t some magical apparition but a studious human whose backgrounds coalesced into this one outstanding performance that would never be repeated in the same context.

After inaugurating the sport for women, Lyon refused to compete as a bodybuilder, and to this day none of her successors have done it like her, focusing more on musculature than on her synthesis of movement, spirit, entertainment, and site-specific sculpture. “Musclée mais douce” (Muscular but soft), an Elle France feature from 1981 repeated, in awe of her balance. Lyon was careful not to build her muscles to an even potential; she tore, grew, toned, and left alone what she wanted to, honing a total package.

From bodybuilding, Lyon pivoted back to art, but stayed on stage and camera. She was photographed and filmed by Mapplethorpe and, later, by the artist Tadanori Yokoo in Japan. She also appeared in a few films. In the trashy horror Vamp (1986), starring Grace Jones, Lyon plays a guard in a leather harness and pasties. When the guy she’s guarding is attacked, she turns into a zombie-vampire-demon out for the kill who’s impaled almost instantly and improbably by a high heel that’s not even a stiletto, it’s stacked. In Three Crowns of the Sailor (1983) Lyon wears pasties again, two sets of them during a striptease. Before this she’s seen dancing on a cabaret stage in a bikini, introduced by a man’s voice-over as “the femme fatale, the woman who does what she wants.” When this man asks to be alone with her, she replies, “Art is solitude.” It’s a French film and Lyon is either speaking French or she’s been dubbed. To date, in all my research, I’ve yet to hear Lyon’s voice in her native tongue.

But by all accounts, she talked a lot. Journalist John Lombardi said so in his Spy Magazine profile in October 1991: “Lisa is a big-time monologuist,” he wrote, “in the awesome league of Neal Cassady and Robin Williams. There is a Formula One quality to her sentences, as if she were afraid the phrase behind might skid and blow out its syntax if she paused.” Travel journalist and novelist Bruce Chatwin echoed this in his introduction to Lady: Lisa Lyon:

Lisa is not inclined—ever—to be tongue-tied; and in any snatch of conversation, you’d be as likely as not to hear her dilating on the principles of Taoism, the future of the planet, her old friend Henry Miller, or the percussion cap needed for her Remington shotgun: “I like weapons. They are a part of my reality.” Or she might explain her concept of the prototype of woman of the eighties: her concept of a woman’s body (“neither masculine nor feminine but feline”), her concept of body building as ritual, and her concept of ritual as Art.

When men write that Lyon talked a lot, they tend to summarize her, as above. Her speech is gestured to in their frame. Did she have a Southern California accent? Dimitri Levas, a collaborator and close friend of Mapplethorpe’s, now a vice-president of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, can’t remember what Lyon’s voice sounded like. Then he says, “She could be pushy, domineering.”

Levas has wonderful takes on Mapplethorpe’s side of his collaboration with Lyon. He believes, for example, that Mapplethorpe probably dedicated Lady: Lisa Lyon to Patti Smith because he was planning on doing a similar book with her—a blockbuster photo book of one iconic woman—but when Smith was unavailable, having married MC5 guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith and moved to Detroit, Mapplethorpe turned to Lyon, another androgynous model who embodied an ideal he’d pored over in his youth. “When Mapplethorpe was a young man,” Levas explains, “he had a number of big art tomes that he loved and one of them was of Michelangelo. If you look at Michelangelo’s women, they’re basically men’s bodies with women’s faces and boobs.”

Lyon and Mapplethorpe came together to make hundreds of photographs that would end up in Artforum, in a book, at the Leo Castelli Gallery, and in 1982’s Documenta 7 exhibition in Kassel, West Germany. Spy’s Lombardi claimed it was Mapplethorpe’s exboyfriend and studio manager Marcus Leatherdale, also a photographer, who introduced Mapplethorpe to Lyon. Chatwin wrote that Lyon was already “on the lookout for the right photographer to document” her “ephemeral” art as “a sculptor whose raw material was her own body.” Like Lee Miller shot by Man Ray, authorship of Lyon × Mapplethorpe’s photographs is obviously shared. She posed, he shot. Their aesthetics were similar: Lyon was already wearing black leather when they met. She was even wearing a veil on their first meeting, just like on the cover of their book. “The pictures are a little hard,” Lyon remarked, “like us.” If only by didn’t imply authorship. Their work was always titled like this, Lyon by Mapplethorpe, which bothered some feminist critics who felt it undermined the work’s collaborative nature. The root of by in Old English, though, also means around, about, near. And Lyon was a radical intellectual—she dedicated Lady: Lisa Lyon to Huey P. Newton, founder of the Black Panthers—so maybe she knew and didn’t mind being by others in the original sense of the term. She was by others often. In Helmut Newton’s frame, she swings on a trapeze and pulls a steel chain. In Yokoo’s, she wields both chalice and blade. By Leatherdale, she wears a veil. By Resnick, she’s all rippling back.

According to Lombardi, Huey Newton and Mapplethorpe were Lyon’s lovers, as were Yokoo, Dennis Hopper, Jack Nicholson, and others. Lombardi’s Spy article is the most comprehensive look into her life and work, answering one of my questions: Lyon did have a cat, named D. D. Puss. Lombardi’s article is riveting, salacious, and undoubtedly unfair. Remember how Tonya Harding, Anita Hill, Pamela Anderson, Ilona Staller, and Monica Lewinsky were treated in the press; the ’90s could be cruel to their female athletes, political femmes, and sexpots. Was Lyon a PCP-huffing muse who, as Lombardi portrays her, got lost in the sauce after mind-melding with psychonaut John C. Lilly? Maybe. Unlike the gentle McKenna, who advocated once-a-year psilocybin trips, Lilly sought transcendence through ketamine doses that were just short of deadly. The inventor of the isolation tank, celebrated for his CIA and/or self-funded experiments with dolphins, Lilly inspired two Hollywood films and multiple generations of young men desperate to reenact California’s patriarchal hippie counterculture. It’s hard not to look back on his work and see anything but animal abuse, bestiality, the exploitation of his young female employees, and a colonial relationship to nature (he trapped dolphins in a house full of pools and tried to teach them English as if this would prove their intelligence, not to mention that a pretty twenty-something employee had to routinely relieve a teenage male dolphin sexually.)

Lyon and Lilly met in 1986, following her two years in Japan, where she was a big star, recalling perhaps for Japanese audiences the celebrity author and kendōka, karate-ka, and boxer Yukio Mishima. (Acker’s bodybuilding essay is a Western mirror of Mishima’s 1968 Sun and Steel.) I trust Spy’s Lombardi as much as I do Lilly, so I’ll be generous and say that what Lyon entered into with Lilly remains a mystery. Drugs? Love? God? Lyon herself said, back in 1982, while speaking of her new (and ultimately short-lived) marriage to the French musician Bernard Lavilliers, “I need a collaborative reality.” She seems to have satisfied that need throughout her life, with Gold’s Gym; with Mapplethorpe, Leatherdale, Resnick, and co.; with Lavilliers; with Yokoo; and, not ultimately, with Lilly. As far as collaborative realities go, the one with Lilly must have been a trip; we’re talking astral travel, aliens, psychic communication, transhumanism, and enough money to pursue these things without limits. He was seventy-six to Lyon’s thirty-eight when Spy quoted her saying that the body, once her prized medium, had come to seem “increasingly irrelevant.” Lyon wasn’t the first of Lilly’s former lovers to be adopted by him as a daughter, and she wouldn’t have been the first to lose herself, if temporarily, in druggie hippie drop-out culture. Lilly died in 2001. Lyon married actor Alan Deglin in 2009. He died in 2020. She passed away three years later. Rare late-life photos of Lyon found in the comments section of her Legacy.com obituary show her looking fierce, fit, and happy with gray hair, black Wayfarers, and leopard print, always, somewhere on her body.

I was wondering out loud about Lyon’s disappearing act when Wet’s Koren suggested that “she was almost too smart to be famous. She understood the game and may have lost interest in the self-aggrandizement part of things.” I liked this explanation better than my feeling that the game wasn’t in her favor.

If Lyon encountered failure in bodybuilding, it wasn’t the failure Acker described in her essay, although it was a failure Acker experienced in her youth: the failure for her work to be considered art. That’s what Lyon seems to have wanted. She didn’t want to open a chain of gyms in her name, because she was an artist. She may have agreed to a commercial book but Body Magic turned out strange, mixing self-help clichés with illustrated exercise demos, microbios of historic strong women, and intellectual concepts. (An excerpt: “Changing your body goes beyond just changing your outward appearance; it can have a significant influence on everything in your life. As Freud said, ‘The body is the ego.’”) Like a twentieth-century artist, Lyon did tons of drugs, had lots of sex, and innovated an expressive aesthetic following a troubled childhood marked by compulsive behavior. She socialized with artists and collaborated with them as an equal. She didn’t make objects of her own, though, and that’s a requisite for artist status in the West, where the fiction of the individual hero and the fact of something sellable are more creatively valuable than practicing within the truths of interconnection or our ephemeral human nature. Had Lyon taken her own photographs like Francesca Woodman or Lee Miller, had she packaged her concepts in cool Chris Burden–like documents, would her obits have called her an artist rather than saying “she saw herself” as one? Maybe.

The image of Lyon that was cut out of Danto’s Playing with the Edge wasn’t, as I first feared, one of bulging veins and muscles; a queer threat. It’s a picture of her emerging patient-predator-like from the sea, as languid as she was ever pictured. Baywatch before Baywatch, it’s easy to imagine who took it and why. And as banal as masturbation is, that cutout may be a clue. To this day the art world has little room for hot young femmes, just as the status of art is rarely bestowed on representations of them unless they’re debased, exploring feminine abjection and grotesquerie, or captured by another artist, ideally male. I’ve no doubt this bias had something to do with why Lyon left the art world and pop culture in 1986, at the same age at which Jesus died “for somebody’s sins,” as Smith sings, “but not mine.”

1You can find it on Fletcher’s website; https://www.joelfletcher.com/creative-process/?post=bodybuilder-sculpture-zane (accessed December 16, 2023).

All Robert Mapplethorpe artwork © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.