David Frankel is the former editorial director in the publications department of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was an editor at Artforum in the 1980s and ’90s and remains a contributing editor there.

So many of the artists we read about in the art magazines, let alone the glossies, are doing fine in the market. They are established or at least up and coming; in gambling language (an undercurrent in a certain sort of art talk), they are favorites, contenders, front runners, picked to win. If they’re in the upper tiers of success, we may find ourselves reading about their houses in lovely parts of the world, or about their studios, somehow both stylish and elaborately functional. And needless to say, we wish them joy in these things. But for every front runner there is the rest of the field; for every leader of the pack, a pack.

I first met Jeff Perrone in about 1988, through my then partner the artist Elaine Reichek. The two were dear friends, having bonded during the New York AIDS crisis, when both had shepherded people all too close to them through the last days of their lives. Elaine told me Jeff’s story before I met him: the son of wealthy parents, his father a real estate developer, he had grown up in part in San Francisco, but because he suffered from asthma, the family had installed him alone except for a housekeeper and a chauffeur in a second home in Stinson Beach, a seaside town in Marin County. There the air was cleaner than in the city and his health was safer; the family would visit, but Elaine had the sense that they were happy to have a reason to be free of him. When I eventually met Jeff, I could oh so easily imagine him as a difficult kid, a condition for which isolation and exile are not necessarily solutions, but they had actually turned out well for him: he loved Stinson Beach, loved his support staff, and was happy to take on the job of bringing himself up by himself. And he did it well, too: ferociously smart, he eventually studied linguistics at Berkeley, by his early twenties was writing for Artforum and other magazines, and was soon on staff at Arts, producing essays and reviews that would eventually get him described in Artforum as “a founding figure of the Pattern and Decoration movement” of the 1970s. Professional writing and editing, though, did not satisfy him, and in time he largely gave them up to make art.

After Jeff’s unexpected death, in the spring of last year, it fell to Elaine to find and contact his family in California, and in the process she discovered that much of this story was fiction: he was actually the son of a US Air Force colonel, the family comfortable but not rich, and though he did love Stinson Beach, having visited it often as a child, he had never lived there and had grown up conventionally at home. For something over four decades, long-term friends including Elaine, the artist Jimmy Wright, the critic Max Kozloff, the artist Joyce Kozloff, and others—not a large group; many in Jeff’s community had died during the AIDS years—had accepted his fantasy biography, or variations on it, having no reason to doubt it. Why the tall tale? I can’t say. Many come to New York to reinvent themselves, but where most devote those efforts to their futures, Jeff went whole hog and threw in his past. He did not invent his intelligence and insight, though, which are there in his published writing for everyone to see.

The first time I met Jeff, over dinner at a barbecue place on West 72nd Street, he sat more or less with his back to me, as far as the table shape allowed it, and monopolized the conversation, talking only to Elaine and ignoring everything I said. A few years later, when I’d gotten over that, I was having lunch with him once across the street from the offices of Artforum, where I was on staff, when the magazine’s then editor, Jack Bankowsky, walked in; thinking it could be helpful to Jeff and Jeff’s career to meet Jack, I waved him over, introduced him, and Jeff snubbed him just as he’d earlier snubbed me. (Jack took it in stride; if anything he was amused.) On another occasion I saw Jeff be equally rude to Betsy Baker, then the editor of Art in America. When I worked in the publications department at the Museum of Modern Art, I would sometimes hire Jeff as a proofreader to get him some income; his work was fine but infuriating, because he would fill the margins of the pages with derogatory comments about the writing when all I wanted to know was whether it had typos.

Jeff’s authority issues went way back. In a letter from 1977 generously shared with me by a longtime former boyfriend, Craig Monson, Jeff wrote of a lunch among well-known artists, photographers, and editors, “I admitted that I thought anyone could do photography. I also expressed the opinion that dance and theater and opera were stupid, which did not sit well with everyone.” It certainly wouldn’t have, and I doubt it was true—according to his family, Jeff had loved music as a teenager, playing the piano, and the organ at church on Sundays, and actually composing music—but I’m sure the outrage amused him. As time went by, though, his desire to offend seems to have grown less playful and more entrenched, for reasons I never fully understood but speculate came from the acute difficulty for him of reconciling confident, even arrogant belief in himself with the infantilizing effects of many artists’ lives. In the struggle to get their work shown, seen, and understood—professional tasks quite separate from the struggle to produce art—proud people may end up feeling like supplicants: they need someone (a dealer, a critic, a curator) to give them something (representation, attention, inclusion in a show) and can’t make it happen by themselves. All they can do by themselves is make their work.

As an artist, Jeff was a distance from unknown, but an equal or greater distance from earning enough to live on. He lived in a comically grimy tenement apartment above Yonah Schimmel’s, the ancient knishery on Houston Street. He had worked for some time in clay, making ceramic sculptures and tiles, and forcing his tiny life/work space to accommodate a kiln; in those years a layer of clay dust had added to the level of unvacuumedness. Although he was HIV-positive and immunocompromised—he barely survived the ’80s before a drug cocktail emerged to save him—he nevertheless smoked heavily, so much so that the Chicago gallery that staged his final show, which opened a few weeks after his death, came to smell of cigarettes, a perfume imported from Houston Street along with the art. So—in many ways a role model for no one, a man with advanced skills at shooting himself in the foot. But I completely respected and enjoyed him. Thinking about him now, I remember the critic and painter Manny Farber’s famous distinction between white elephant art and termite art, the former “an expensive hunk of well-regulated area,” the latter art that “goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and . . . leaves nothing in its path.” The termite artist tunnels blindly ahead until the house comes down, working best “where the spotlight of culture is nowhere in evidence, so that the craftsman can be ornery, wasteful, stubbornly self-involved, doing go-for-broke art and not caring what comes of it.” That sounds like Jeff, in his cantankerousness, his concentration on what he was doing, and his willingness to alienate those who could help him. If few would want totally to emulate him, there should be, must be, a place in the world for artists of his kind.

Jeff died in inexpressibly sad circumstances, of a heart attack when he was home alone. A few days went by before anyone realized he hadn’t recently checked in. Elaine found and cold-called his next of kin and she and Jimmy ended up acting as the family’s unofficial agents in New York, working to clean out the apartment above Yonah Schimmel’s and to prepare for the settling of the estate. The process was familiar to them: both had had to handle this task for other late friends during the AIDS crisis.

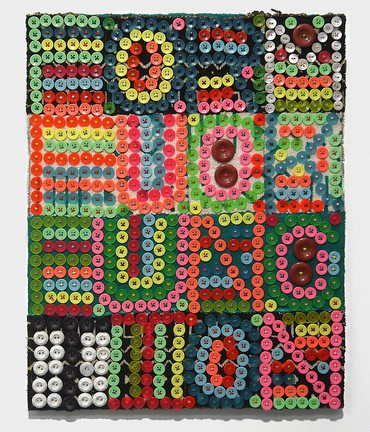

And as of this writing that’s where things stand, except, I haven’t said much about Jeff’s work. But it isn’t really the subject here, and I’ve written about it elsewhere in the past; so I will say only that I loved it.

Artwork © Jeff Perrone

Photos: courtesy Marinaro, New York