Currently Director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Dr. Simon Groom lived in Japan and Italy before starting his career at Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge, where he curated the first UK retrospective of the Japanese group Mono-ha. He later moved to Tate Liverpool as Head of Exhibitions.

Jenny Saville remains one of the most complex, ambitious, and instinctive figurative painters working anywhere in the world today. She erupted into public consciousness in 1992 with her graduation show at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA), which caught the eye and wallet of the British collector Charles Saatchi. Since then she has continued to make works that extend the subject matter and test the possibilities of painting, as well as powerfully articulating a very contemporary consciousness of the experience of being in the world.

As the late, and great, art historian Linda Nochlin wrote in 2003, the formidable power of Saville’s paintings derives as much from their sheer scale as from the ambiguity of their subject matter. But Nochlin also identified the ambiguity of the work’s formal language, “a language that inscribes a conflict at once visceral and intellectual between the assertive pictorial naturalism of the subject matter and the openly painterly, at times almost abstract, energy of the brushwork. It is as though a Sargent had mated with a de Kooning before our eyes, and the coupling was more of a violent struggle than a love match.”1 This sense of tension, almost violence, is a defining characteristic of Saville’s work to date. Her portraits of large, mostly female nude bodies—“I try to find bodies that manifest in their flesh something of our contemporary age”2 —provoke discomfort as much as fascination, repulsion as much as attraction. The technical bravura of the brushwork vies with the often brutalized appearance of the subject matter; lyrical passages of abstraction coexist with figurative details, the visceral with the conceptual. If the mark of intelligence, as Scott Fitzgerald once defined it, is the ability to hold two contradictory beliefs simultaneously, then Saville is a super-smart painter.

Never one of a group, or identified with any particular movement or style, Saville has remained distinct and distinctive. She arrived in Glasgow in 1988, when figurative painting was strong at GSA but was identified almost exclusively with the male painters who came to be known as the “New Glasgow Boys,” Steven Campbell, Stephen Conroy, Ken Currie, Peter Howson, and Adrian Wiszniewski. At the same time, painting was being challenged as a self-sufficient medium nowhere more vigorously than at GSA: the school’s newly founded Environmental Art program, which emphasized context, concept, and critical theory, led to a fertile period of experimentation that was to galvanize a whole new generation of artists, from Christine Borland and Cathy Wilkes to Douglas Gordon and Richard Wright. In this context, painting itself seemed to some to have arrived at a dead end, being seen as reactionary and perhaps, more crucially, inadequate to contemporary expression.

when I was at college, everybody was into Kiefer and Baselitz, and big-time macho paintings. If you painted figuratively, it was seen as a little quaint. I liked those big paintings. . . . And I didn’t feel like being figurative was quaint.

Jenny Saville

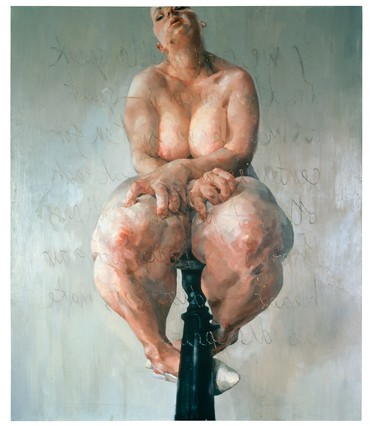

This milieu forced Saville to test the medium all the more. The interest in the body, and particularly the manipulation of the body, and the construction of a gendered identity, became central to her work at GSA, where a language of contemporary discourse around feminism and critical theory helped to inform her thinking. Propped (1992) shows a nude woman wearing silver shoes, and perched precariously on a Singer-sewing-machine stool. We encounter the figure first through her knees, large in their proximity to the viewer, as our eye then follows her hands and travels up the body to be met by the model’s direct stare, a look that appears to issue us a challenge, confident and defiant in the assertion of its own physical encounter. Scored in reverse lettering across the surface of the painting, literally carved out of the thick layers of paint with a lino-cutter, is a quotation by the French psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray: “If we continue to speak in this sameness—speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other. Again, words will pass through our bodies, above our heads—disappear, make us disappear.”3 In Saville’s degree show at GSA, she installed the work with a mirror placed opposite it, a simple device that made the words legible and at the same time placed the viewer reading them firmly within the symbolic space of the painting.

Propped is also a massive statement of ambition, seeming to combine two quite contradictory and irreconcilable traditions. The presence of the script asserts the flatness of the picture plane, a key feature in the development of painting as described by Clement Greenberg. But Greenberg applied his theory of historical advance principally to American abstract art, and Saville’s work is figurative—and not only figurative but absolutely contemporary in its depiction of a body type that is familiar but not readily celebrated as heroic in modern times. While large bodies are of course not exclusively contemporary, they are very much a contemporary subject. At the same time, they also refer back to earlier periods of art history when such subjects were more commonplace, and Saville has spoken of her admiration for Rubens. Similarly, she looked to the past in her search to give form to the body, and the unusual perspective of Propped clearly owes its inspiration to her study of art history: “When I was at Glasgow, I was obsessed with Michelangelo. All my early Prop paintings are based on his big knees coming out from stone, in those unfinished slave sculptures.”4 The title too is significant: referring literally to the support on which the model sits, it also conflates the idea of the woman with that of the prop, suggesting a temporary state, a proxy, something constructed, often simply for the sake of show. Although large in scale, the subject of Propped is riven with the idea of impermanence, almost literally figuring a sense of precarious balance that would run throughout Saville’s work.

At well over six feet tall, the figure in Propped, and in the related painting Prop (1993), is made to feel even larger by the perspective, which forces the viewer to look up at a body literally too big for the frame. At a moment when there was open criticism of Saville’s decision to paint such a subject, the works’ scale constituted an assertion of the validity of the figure, and particularly of the female nude, as a subject matter for painting. It was also a reaction to the status of painting at a time when the medium was overtly identified with a particular kind of mostly male, large-scale work, perhaps masking a very real concern over its continuing adequacy:

They actually shocked me, those paintings being so big now. I wanted to be taken seriously as a figurative painter. I remember, when I was at college, everybody was into [Anselm] Kiefer and [Georg] Baselitz, and big-time macho paintings. If you painted figuratively, it was seen as a little quaint. I liked those big paintings. I loved [Jackson] Pollock and [Mark] Rothko and all those enormous paintings. And I didn’t feel like being figurative was quaint. And I didn’t want to make paintings that were going to go in someone’s living room. I wanted to make paintings that were going to be in big spaces, that would be taken seriously.

The scale of these paintings forces the viewer into a powerful, even uncomfortable physical confrontation with them. It also emphasizes the materiality and construction of the painted surface itself. In works such as Branded (1992), Plan (1993), and others, the women’s flesh shows markings in preparation for plastic surgery, transforming the body into a territory to be mapped. Saville recalls that in Glasgow in the early ’90s, knowledge of cosmetic surgery was almost nonexistent, and she would have to explain what she was doing:

“What are these target marks?” people would ask, because they simply hadn’t come across the notion of plastic or cosmetic surgery. I used to spend my whole time describing liposuction to people because they would say, “What is it? That’s a weird word.” And now I don’t think there’s anyone in the Western world who doesn’t know what that is.

I try to find bodies that manifest in their flesh something of our contemporary age.

Jenny Saville

Another work from this period, Cindy (1993), was based on an image Saville had spotted in a magazine article about a woman who had used her inheritance to rid herself of any resemblance to her family. She had even changed her name, wanting to look like a Sindy doll:

I liked this idea of a kind of fictional normality that this woman had created. It was like a mask, which is why the piece looks the way it does. It doesn’t have a kind of form or an edge.

Saville’s fascination with the representation of gender and the manipulation of the body was deepened after she left GSA, when she went to New York, at the invitation of one of her collectors, to learn more about cosmetic surgery with the surgeon Barry Weintraub.

I already knew I was going to seek out a surgeon. I just found it completely fascinating. There was a certain egotistical side to the surgeons, I have to say, and also the patients, the people who went there thought they were ill. They thought they were sick and I was quite intrigued by that [idea] that if they went through this process, they could come out more natural than they were when they went in. So they had this idea in their head, this fiction of what their natural self should be and the surgeon was going to help them reach that point.

Matrix (1999) takes as its subject Del LaGrace Volcano, who was born intersex, raised as a female, and was then transitioning to a male. Volcano was the first such subject with whom Saville worked. Like Cindy, Matrix undermines the conceptual underpinning of traditional portraiture, identifying its interest precisely in the subject’s refusal of a stable identity. The subject matter is also contemporary: the body it shows, thanks to surgery, could not have physically existed previously.

When I started researching surgery, there are a huge number of before and after pictures. So when you had somebody who is in between, like Cindy, she’s not before or after. . . . I was interested in the state of in-betweenness, that’s what kind of got me. I was reading a lot about the monstrous feminine—just lots of issues around the body. It was a very contemporary issue—identity, the possibilities of changing yourself, and the same with that of your gender.

It is extraordinary how radical the reconceptualization and normalization of gender issues have been in the past twenty years. Today, Facebook offers fifty-six gender-identity options, and Tinder thirty-seven. But when Saville made these paintings, she remembers:

People didn’t even realize that you had bodies that were in-between male and female unless you were in the medical profession, or someone who had a particular interest in that. So I tended to spend a lot of time explaining things, talking to a journalist or an art historian about the issues. In common language, those terms were not there.

The revelations for Saville of watching a surgeon at work extended beyond the body, it informed her practice as a painter:

I liked this idea that flesh was something you could manipulate and move, in the same way you do with paint. So the idea of paint as a substance, as a potential body, and flesh being moved by a surgeon, came together. And I think watching a surgeon at work actually changed my painting technique because I could see what the layers of flesh were like, and the manipulation of a human body, in the same way that you move paint around. And I wouldn’t have made such scraped, thick paint had I not seen the surgeon at work. It was really influential.

The idea of paint as a kind of liquid flesh became more instinctive for Saville when she was working on the Stare series, from 2004 to 2011: “I was working on the Stare Head when I was pregnant with my son, and it was so profound to be making flesh in my body while I was trying to produce flesh on a canvas.” Struck by the port-wine stain on the face of the subject in a small photograph in a dermatological textbook, Saville produced a number of works based on the image. Uncertain in gender, the face in these paintings stares out somewhere slightly beyond the viewer’s gaze, appearing not fully present yet physically insistent: “I guess there’s something enigmatic about a person, or a look, that runs through my work. It’s a kind of blank intensity.” Saville has spoken of how the repeated address of the same subject gave her the freedom to test and expand her ways of working, so that her paintings, while remaining figurative, also became more abstract. She was able to explore abstraction in her handling of the paint, moving from the particular to sensations and ideas with more universal resonance. The Stare paintings demonstrate this thought in process, introducing the paradox of combining the durational notion of time with a stasis corresponding to the work’s subjects—the stare, a prolonged act of fixed looking.

she has recreated painting in the image of our own ominous and irrational times, and that in itself is no small achievement.

Linda Nochlin

The introduction of time, and the increasing emphasis on the physical passage of the paint, demonstrate the increasing complexity of the artist’s conceptual vision and technique. While the body remains the focus of works such as Compass (2013) and Ebb and Flow (2015), made largely in pastel and charcoal, there is a shift from single to multiple figures and a merging of figuration and abstraction. The transparency and fluidity of drawing allowed Saville the opportunity to figure multiple realities simultaneously. This was partly a result of the way she worked, finding inspiration in the countless images that catch her eye, whether from art history, medical textbooks, or Abu Ghraib, the prison run by US forces outside Baghdad after the Iraq War. Pinned to the walls of her studio or scattered across its floor, these images facilitate a way of looking that corresponds closely to the way we process our current experience of the world, with its vast range of eclectic, fragmentary, and simultaneous visual imagery: “I don’t have a hierarchy of what I look at. . . . Google images changed everything: there is no concept of scale or time. A page-three girl and a prehistoric cave painting exist on the same page—it’s so exciting.”

The shift to multiple figures also coincided with Saville’s pregnancy:

I had kids and that changed everything—there was a shift between the heavy, singular objects, basically of bodies, to multiplicity. So I’m watching a body grow and a body moving around, and then one year later I had another child, so I had two babies within one year and two weeks. So I was doing drawings because I was so busy with the kids and I just started drawing one on top of the other, on top of the other, and the multiplicity of lines became more descriptive to me about humanity or human bodies moving, in terms of my kids. Then that related me to old master drawings again.

To deal with motherhood, Saville embarked on a series of works directly referencing some of the most iconic works of Western art, from Michelangelo’s Pietà to Leonardo’s great Burlington House Cartoon in London’s National Gallery. She also worked from life, taking up to 2,000 photographs at a sitting of couples who came to the studio to model for her:

Instead of setting up a very still image, I might start like that and then they just move, and so I photograph constantly, almost like constantly drawing. And then a lot of those images are of bodies in movement, as they shift from one position into another position. And instead of trying to seek out one, I just have all these images scattered over my studio floor, from which I pick certain ones out, which I mix with art history. So I might have, for example, an ancient Greek leg mixed with the leg of a model I’ve worked with, mixed with a piece of Picasso, and something from Matisse. I just see color combinations and so it becomes this very organic process.

As drawings set one on top of the other, the works remain open-ended, layered, full of possibility. The lines both make and obliterate, blurring the edge between creation and destruction. The ambiguity of the figures themselves—whether they are male or female, whether they are different figures or variations on the same figure—reflects the artist’s own more profound and complex experience of self:

I’m not drawing a hermaphrodite. I’m drawing many bodies together so that the gender becomes fluid. So parts of the male body become the female body, and that becomes really exciting, because it almost represents more what we’re like as humans, rather than these separate sexes. We’re made up of masculinity and femininity, so those are the things that become interesting by layering them up.5

Although the work is figurative, the eye is never allowed to settle or rest—it moves ceaselessly through the work’s tangle of lines, in a constant effort to read, re-create, make whole, as if the only thing that kept the work together was the very act of looking.

That’s my aim. That comes from looking at Pollock, hours and hours of looking at Pollock, or de Kooning. With them, your eye is active in the making of the picture and I thought, “Why can’t figurative painting do that?” It doesn’t mean the figures are moving, but you employ those techniques in a figure so you can create a movement through the figures with the paint and the line.

Saville’s ambitious evolution of a radical visual language for the fluidity of identity could not appear more contemporary. But in fact these concerns connect directly to a far older tradition, exemplified not least by that great handbook of change, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which deals so explicitly with the ambiguity of gender and the instability of the self. Drawing on an older Hellenistic tradition of metamorphic myths, the mythical setting for many of the stories Ovid recounted was Sicily, a country settled by the Greeks, a crucible for the Roman Empire, and a foundation of Western culture.

Saville was to spend time living and working in Sicily’s capital, Palermo, between 2003 and 2009, where she came to appreciate the hybrid formation of culture through the layering of time in successive waves of immigration. Her time in Palermo had a powerful influence upon her work:

After I had children, I wanted to find an art that felt like the rawness of giving birth. I lived in Sicily for a long time, so being in Palermo around those myths and ancient history really linked me to that and the myths of the ancient Greek world . . . gods and goddesses and the power of fertility. So that seeped into my work a lot then and it’s a big driving force in my life now, especially in the drawings, a kind of creative urge. I’m much more interested in what the life force is of a creative urge, or how to make something and destroy it and bring it back. Through that cycle, which is basically a cycle of nature, you get to a greater truth, or a more interesting area of the work. I only really managed to do that through looking at ancient art.6

I’m really passionate about trying to make what I do relevant.

Jenny Saville

Archaic and classical Greek sculpture, which Saville encountered primarily at the British Museum, London, and the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, is an art almost exclusively about the body. In particular, the fragments of ancient sculpture, which in their cool and pristine detachment retain a power of form and suggestion unmatched in the history of art, have provided a formal and imaginative inspiration for Saville’s work.

A comment of Nochlin’s from 2003 remains uncannily prescient today: “Jenny Saville has indeed returned painting to its origins at the same time as she has made it new. . . . above all, she has recreated painting in the image of our own ominous and irrational times, and that in itself is no small achievement.” Saville remains a remarkable artist because so instinctive, because unafraid of contradiction, because only too conscious that the risk of engaging with the art that has come to define us over the past 2000 years could not be greater, but that central to risk is the promise of change:

I think I’m really passionate about trying to make what I do relevant. There was a lot of guilt about being a figurative painter, and it’s really hard to be a good figurative painter. You can adopt a sort of bad painting idea, but that was just too novel for me. I guess it wasn’t my thing. And so, I desperately wanted to be serious about it. I didn’t want to be banal, deliberately banal, because all the great art that I like has been serious. So I thought, “I have to try to do this or I might fail desperately.” But I definitely want to try to navigate my time in a serious way and if that means I look stupid or sometimes they’re naff, then that’s something I’ll just accept. That’s a risk worth taking.

1Linda Nochlin, Migrants, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003), n.p.

2Jenny Saville, in Simon Schama, “Interview with Jenny Saville: New York, May 2005,” in Jenny Saville (New York: Rizzoli, 2005), p. 124.

3Luce Irigaray, “When Our Lips Speak Together,” trans. Carolyn Burke, in Signs 6, no. 1, issue titled “Women: Sex and Sexuality, Part 2” (Autumn 1980), p. 69.

4Saville, in conversation with the author, January 12, 2018. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations of Saville are from this source.

5Saville, in Elena Cué, “Interview with Jenny Saville,” The Blog, Huffpost, June 8, 2016, available online at www.huffingtonpost.com/elena-cue/interview-with-jenny-savi_b_10324460.html (accessed March 3, 2018).

6Ibid.

Artwork © Jenny Saville; NOW: Jenny Saville, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, March 24–September 16, 2018