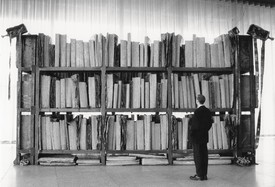

In Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures and drawings, everyday settings, objects, and surfaces transform into ghostly replicas that are eerily familiar. Through her use of the casting process, her subject matter—ranging from beds, tables, and boxes to water towers and entire houses—is freed from practical use, suggesting a new permanence imbued with memory. Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Fumio NanjoRachel, it’s nice to meet you—I’ve known your work for a long time, but I’ve sadly never had the opportunity to connect with you until now. I’d love to hear your perspective on your past works, from the beginning, and how they led to your new project in Kunisaki.

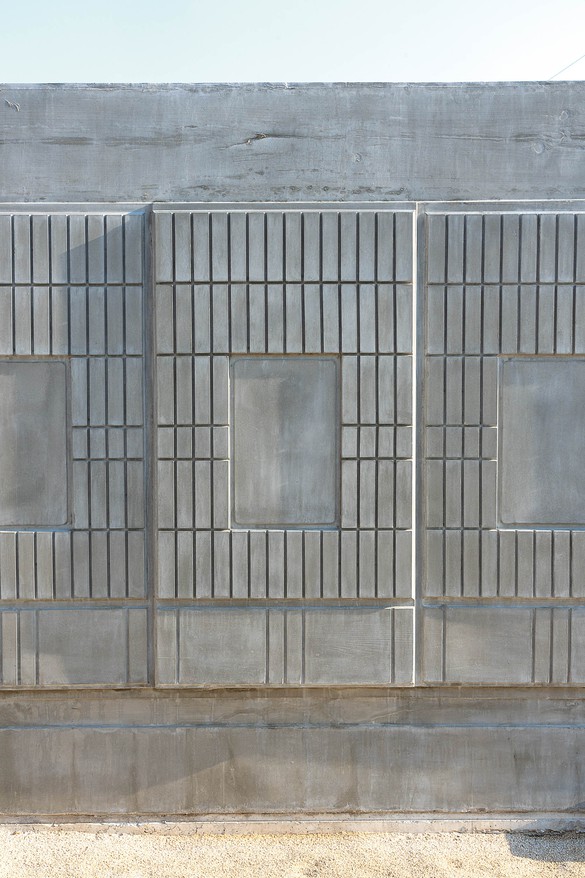

Rachel WhitereadI think I’d start in 1990, with Ghost, the first architectural sculpture I made. When I decided to make that piece, I wanted to use a small Victorian family room, similar to a room we had in my childhood home but also the kind of place I lived in when I first left home. Within that room I wanted there to be a window, a door, a fireplace, cornicing, and a skirting board; I then used those five elements to break up the surface of the piece architecturally and sculpturally. It was all made from the inside out, and then I took it to my studio and put it on a framework.

The next piece I made, which was in a similar vein, was House [1993]. It was the cast of the interior of a Victorian house, which was made by simply—well, not simply—by spraying concrete inside the house and the building and then removing the building. This involved working with engineers, and it was the first time I worked in a way that I do quite often now, with engineers, builders, and larger teams.

FNAnd where was this located?

RWHouse was in the East End of London. It took about two years to make and then it was up for just a short period of time, about four months, but it became an interesting point of contact for people talking about contemporary sculpture, politics, housing, and all sorts of other issues that were very much in people’s minds in [Margaret] Thatcher’s Britain, which was a difficult time politically.

FNIt was controversial, wasn’t it?

RWYes, it was very controversial. There were the political reasons that I just touched on, but also there was very little public sculpture being made and put in the street like that, so people were surprised by it. They reacted, first of all, with a lot of interest and discussion. Later on it became a sort of political pinboard. By the end of its life, there was a lot of graffiti, lots of notice boards up, signs up saying “For sale,” and all sorts of things going on. It really had attracted people’s imaginations.

FNSo what happened to it?

RWIt was torn down. And then the land was turned into a park, which is still there.

This was really the beginning of making memorials—a memorial to a lost place—as part of my practice, and it later translated into making a Holocaust memorial in Vienna. That was another difficult piece to make. It took about five years to get it made and put in the square; the government changed I think three or four times during the process. There was a right-wing government at one point that didn’t want it to happen. There were suggestions that it should be moved to another place, but my work is site-specific and always has been. I completely refused for it to be moved.

FNIt must still be there?

RWIt’s still there and very well looked after. But again, this caused an enormous political uproar. I was getting exhausted by being a political pawn while making work, so I decided to start working on a group of works that I call Shy Sculptures. The term “shy sculpture” means a work that’s almost hidden away, that minds its own business and that people have to make an effort to go and see.

The first piece in this genre was called The Gran Boathouse [2010] and it was a boathouse cast in concrete on a fjord in Oppland, Norway, about twenty miles out of Oslo. To go there you drive for an hour, and you get to this place that in the summer is on the water’s edge and in the winter is frozen into the fjord. It has this stoic presence; there’s nothing else there.

FNIt’s interesting that some people may happen on the work accidentally. I wonder what they think it is.

RWThere is a discreet notice, and I think in the village there are some more notices about it as a point of interest in the town. But the idea really was to make something blank and understated, something that could be ignored, as we often do with what I call “invisible buildings”—buildings that live in many urban or rural landscapes and that people just don’t pay attention to. It’s about giving these places a voice, however soft.

The next sculpture I made was Houghton Hut [2012], a shepherd’s hut. On grand estates in the UK, they would have these little huts on wheels that could be lifted and wheeled around the estate.

FNSo again, this is far from the town?

RWIt’s at Houghton Hall, near Norwich, a substantial town in Norfolk. The piece is placed within the grounds of the estate.

Another example is a pair of works in California, in the Mojave Desert near a place called Joshua Tree, where a number of artists have made interventions in the landscape. These two works were cast from what can be called shotgun shacks, which are like caravans or temporary sleeping and living places where people would buy small plots of land outside Los Angeles and stay in the desert over the weekend. A lot of these shacks are spotted around the desert and you could buy them quite cheaply. A friend bought these two structures and asked me to cast them, which was done under my direction, first in 2014 and again in 2016. It’s an involved journey to get to them—you have to know where you’re going. They’re quiet works in an extreme environment.

There’s also a work called Cabin [2015] on Governors Island in New York City, a very interesting small island in the harbor that has been turned into a park. Many years ago, when 9/11 tragically happened, I was asked if I would think about how to memorialize the Twin Towers and the tragedy, but I was sure that I didn’t want to do that. I felt it was too early—I felt that it needed time to settle, it needed people to mourn and grieve and gradually something else would emerge. Of course there are a number of memorials there now that are very successful as places of rest and grieving. In any case, I was commissioned to make a work on Governors Island and I decided to do something that was my answer to that early request to make a work in response to the Twin Towers. This is my first piece that’s completely invented. I wanted to somehow represent a place where a loner might live, a hermit or someone outside of society. I also thought about a number of American poets and writers who wrote during the Romantic period. There are a number of smaller pieces around the cabin, pieces of rubbish, cast in bronze, that sit around the edge. It feels as if someone had once lived there and that experience has somehow been fossilized.

FNAgain, the location contains important meanings?

RWYes, it does. From one side of the island you can see where the Twin Towers were, and on the other side you see the Statue of Liberty. These two things juxtaposed against the landscape, with the cabin in the middle of it, for me are extremely powerful.

FNIt’s a hut on the outskirts of Manhattan, of civilization. Huts seem to recur in your work. So most recently, you made a Shy Sculpture in Kunisaki. Had you been to Japan before?

RWI’d been once, just to Tokyo. And I’m looking forward to coming again.

FNThis time the building you worked from was made of wood. Was it difficult in a different way?

RWIt had its challenges. We began with a 3D model that was produced after many discussions. This really gave us a sense of what the final piece would look like and allowed us to assess different decisions. Initially it was extremely difficult to understand what the interior of the building consisted of. From the start, I was very clear that this was too complex to cast as is, so I asked the team to map out what was there. They produced extraordinary digital images of the interior of the building. I gradually began to understand that what was inside was what is referred to as a minka, is that right?

FNMinka, exactly—an ordinary house.

RWThis traditional Japanese house, which resembles an intricate piece of wooden furniture, was inside this much more complicated building. We had to work hard to find the building, and then we had to demolish everything else. I decided that I wanted to keep the walls around the original house as well as the traditional Japanese garden. Once the work has settled in the garden, the garden will replenish itself.

FNHow did you find the building? Were you shown many examples?

RWNo, I was shown the one example and I was asked if I’d be interested in casting it. Initially I thought it was far too complicated, too many rooms. The interior was phenomenally complex; it wasn’t designed by an architect, it was very much a kind of do-it-yourself house. Once I’d figured that out, there was a lot of discussion with the fabricators, who on Zoom worked tirelessly to make sure that the tight deadline was met. You can see the intricacy of the wooden screens and the fantastic detail that they’ve managed to capture, the bulbousness of the back of it where there are cupboards and parts of rooms.

FNIn its location, this one is a bit different: it’s surrounded by neighbors. It’s not completely shy.

RWYou’re right, it’s not completely shy, indeed. But hopefully it will have respect from the neighbors and they will understand its personality and let it be shy [laughter].

Artwork © Rachel Whiteread; photos: Takashi Kubo, courtesy Kunisaki Peninsula Culture Tourism Promotion Project