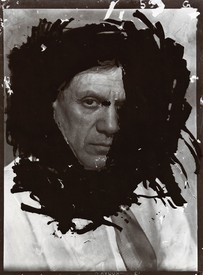

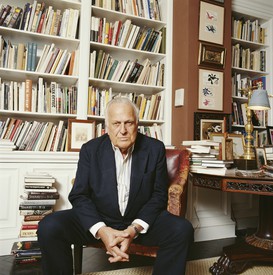

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including eight Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

After the birth of their son, Claude, in 1947, Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot began to spend time in the town of Vallauris, near Cannes in the South of France. Vallauris was the home of a ceramics industry that fascinated Picasso; he was eager to explore this new medium, and in 1948 he and Gilot settled into a small house in the town, La Galloise, so that he could work with the craftsmen at the nearby Madoura pottery. After the birth of their daughter, Paloma, the following year, Picasso acquired a building nearby, a decrepit former perfume factory called Le Fournas, and turned it into a studio in which to paint, sculpt, and store the growing volume of ceramics he was creating. His route there on foot led past a field that served as a dumping ground for the local potters, who used it to dispose of broken pots, tools, and leftovers of metal and wood. Here Picasso would collect whatever caught his eye and carry it to the studio, adding to the scrap already present in the disused factory. Over the next few years the possibilities he saw in this pile would reinvigorate his sculptural practice; from this detritus he would construct some of the greatest sculptures of his career.

“One of the first sculptures Pablo made in the perfume factory was La femme enceinte” (The Pregnant Woman, 1950), Gilot would recall.

He wanted me to have a third child. I didn’t want to because I was still feeling very weakened even though a year had passed since Paloma was born. I think this sculpture was a form of wish fulfillment on his part. He worked on it over a long period of time, I suppose from a composite mental image he had of the way I had looked while I was carrying Claude and Paloma. The breasts and distended abdomen were made with the help of three water pitchers; the belly from a portion of a large one, and the breasts from two small ones, all picked up from the scrap heap. The rest was modeled. The fact that the figure was only about half the normal size gave it a grotesque appearance. It had almost no feet, it swayed perilously, and the arms were too long. It always looked to me like a child-woman recently descended from the ape.1

The ape comparison was not far off the mark; Picasso was concurrently working on sculptures of a baboon (Le Guenon et son petit, 1950–51) and of a goat (La Chèvre, 1950), both pregnant, no doubt also to inspire Gilot. Yet the circumstance of the fetishlike construction of La femme enceinte reinforces her totemic purpose: she is a fertility goddess, and, as Diana Widmaier Picasso has pointed out, should be seen in light of the two casts of the Lespugue Venus, an ivory figure of the Upper Paleolithic period, that Picasso had long kept in his Paris studio.2

The art historian Elizabeth Cowling has proposed that La femme enceinte should also be seen as a response to Edgar Degas’s sculpture of the same subject (1896–1911), an uncommon one in sculpture in general and in Degas’s and Picasso’s oeuvres in particular. The two works share several similarities, especially the symmetry of each figure’s pose. Degas’s figure, however, is a psychological study: it depicts a woman confronting the strangeness of her changing body, and expressing concern or love for her unborn. Picasso’s, on the other hand, is a stoic vessel, and under her plaster skin her distended stomach and breasts are made from ceramic pots—literally containers for water, the medium of life.3

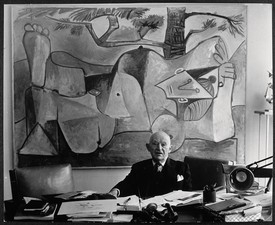

Picasso kept the 1950 plaster original of La femme enceinte for the rest of his life, often placing her in a commanding position in his studio to keep watch over its contents. (She now lies in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.) She appears as such in the painting Femme dans l’atelier (1956), and in a number of photographs of the studio at La Californie, the villa in Cannes that Picasso acquired in 1955. Between 1951 and 1953, an edition of three bronzes was cast from the figure. In the ensuing years, Picasso altered the plaster intermodel from that casting, adding the anatomical enhancements of navel and nipples and more solid feet to stand on. This second state of La femme enceinte was cast in a numbered edition of two in 1959.

1943

May: Pablo Picasso meets Françoise Gilot in a Left Bank Paris restaurant, Le Catalan.

1946

April: Picasso begins to live with Gilot in Paris.

August–November: While Picasso and Gilot vacation on the Côte d’Azur, he is invited to use rooms in the Château Grimaldi, Antibes, as his studio. He creates a number of works in situ and donates others to the Château, which will become the first Musée Picasso in 1966.

1947

May: Birth of Picasso and Gilot’s son, Claude.

Winter 1947–spring 1948: Picasso begins to work in ceramics at the Madoura workshop in Vallauris.

1948

Sometime this year, makes the first of four sculptural portraits of Gilot pregnant, including Petite femme enceinte (Spies 335.I).

May: To be closer to Madoura he acquires a small house, La Galloise, in Vallauris.

1949

January: Publication of Les Sculptures de Picasso, the first study of Picasso’s sculpture, with text by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and photographs by Brassaï.

April: Birth of Picasso and Gilot’s daughter, Paloma. Spring: Creates the second sculpture of a pregnant Gilot, Femme enceinte (Spies 347.I), made from plaster and a palm frond.

Summer: Acquires Le Fournas, a disused factory building in Vallauris, where he sets up one studio for painting and another for sculpture. A room connecting the two is used to store the ceramics that he makes at the Madoura workshop.

1950

May: Begins La femme enceinte, 1er état (Spies 349.I). The work inaugurates a burst of creativity in the artist’s sculpture over the next few years.

1951–53

Casts an edition of three bronzes from La femme enceinte, 1er état.

Summer 1951: first signs of the breakdown of the relationship between Picasso and Gilot.

1952

Summer: Picasso meets Jacqueline Roque, who works at the Madoura pottery shop in Cannes. Roque will become his mistress and the two will marry in 1961.

1953

September: Gilot leaves Picasso, taking their children with her to Paris.

1955

April: Picasso purchases the villa La Californie in Cannes. After he and Roque move into the villa two months later, he will install a number of bronze casts of his Le Fournas sculptures on the grounds.

1956

April: Picasso paints Femme dans l’atelier, depicting Roque sitting in a rocking chair staring at La femme enceinte across the studio at La Californie.

1959

Picasso creates the second state of La femme enceinte (Spies 350), working from the plaster intermodel used to make the bronzes in 1951–53. The base is inscribed with what appears to be the date “15.3.59,” although the “9” is unclear. Photographs of the intermodel by André Villers, dated 1958, confirm the absence of the nipples and navel at that point, making them a late addition to the second state.

1Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), p. 320.

2See Diana WidmaierPicasso, “Between Form and Medium,” in The Sculptures of Pablo Picasso (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2003), p. 15.

3See Elizabeth Cowling, Picasso Looks at Degas (Williamstown, Mass.: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2010), pp. 205–07.

Artwork © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY