Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Alison McDonaldYou worked on this exhibition since 2015. Could you describe the initial steps and give a sense of how you became involved?

Olivier BerggruenWell, the story actually goes back to my childhood. A close friend of my father’s was also a friend of Picasso’s, the English connoisseur and collector Douglas Cooper. He was the one who started investigating Picasso’s work for the stage, which in my view is a crucial and fascinating aspect of Picasso’s activities, one that really permeates much of his career. It’s not as well known as it should be. By reading Cooper I became increasingly interested in Picasso’s collaboration with the Ballets Russes.

AMcdHow did Picasso first begin working on theatrical productions?

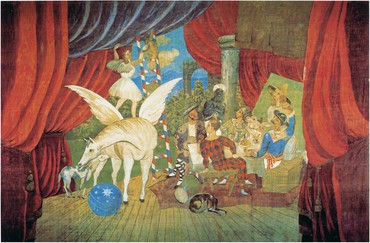

OBIt all started in 1917 when Picasso was asked by Sergei Diaghilev, the creator of the Ballets Russes, to join him in Rome. Picasso accepted the invitation and worked on Diaghilev’s latest production, Parade. With this exhibition we are marking the hundredth anniversary of this 1917 journey to Italy.

AMcdThe show includes works from 1915 to 1925. What was the reason for these specific parameters, rather than spotlighting 1917 in particular?

in many ways the visual shortcuts of the theater are not unrelated to the illusion of painting. So that must have appealed to Picasso. Very quickly he learned the tricks of the trade, how to simplify the lines, to insist on primary shapes, to exclude the unnecessary, all things that make stage design more effective.

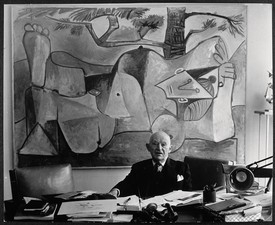

Olivier Berggruen

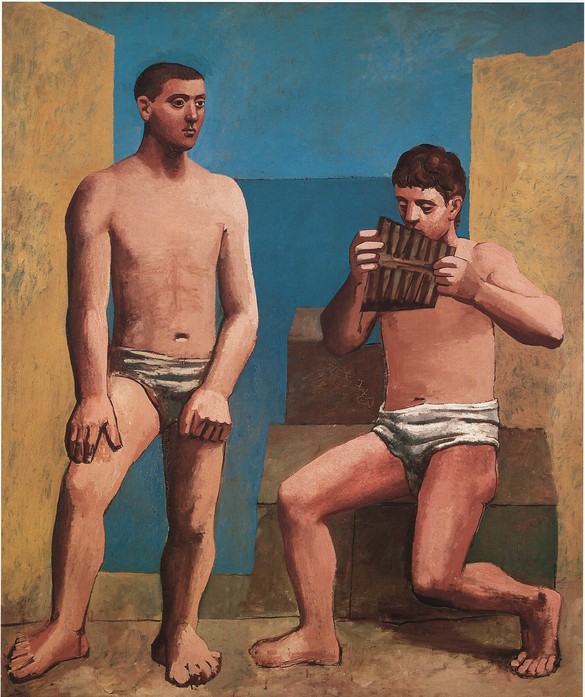

OBWe did not want to simply cover the year 1917, but rather we wanted to show how Cubism facilitates Picasso’s work for the stage, how Picasso uses certain techniques like construction and assemblage to put together his stage designs and, on the other hand, how his encounter with stage design influences his other work. Over time he moves towards a more classical approach but without ever giving up ideas derived from Cubism. The exhibition leads all the way to 1925, where it ends with a famous painting in the collection of Tate Modern, Three Dancers, which is a kind of ritual frenzied depiction of dance in its orgiastic dimension.

AMcdYou’ve just done so much research into this period, is there any story or anecdote that surprised you?

OBWell, Picasso was in Rome, where he starts working on all the aspects of Parade’s production. And, being Picasso, he goes beyond and actually introduced new characters into the ballet. He creates walking Cubist sculptures. But he also does the stage designs, the costumes, and a giant painted curtain. It was fascinating to learn more about the details of the collaborative process.

AMcdThinking about Italy at this time, one can’t help but wonder about the Futurists. Do you suppose that the Futurist artists and their radical views might have affected Picasso in some way during this time?

OBEven before the war, Picasso was visited in Paris by the Italian Futurists. And when he arrives in 1917 in Rome, he is already well known and meets many of the Futurists, who were already making a name for themselves. But it’s interesting that in later years, Picasso was somewhat dismissive of the Futurists for various reasons, maybe because they were so radical in their political outlook. They rejected tradition in a way that Picasso never did. On the other hand, he got on very well with Leon Bakst, the designer of the Ballets Russes, who was a very traditional Russian costume and stage designer. You cannot think of two artists who are more different than Bakst and Picasso. Still they had a huge amount of respect for each other.

AMcdAnd how do you think his work in theater connects to his painting?

OBStage design has a lot to do with visual effects and trickery. You give the illusion of something that is not there through shapes and forms being seen from a distance. Yet in many ways the visual shortcuts of the theater are not unrelated to the illusion of painting. So that must have appealed to Picasso. Very quickly he learned the tricks of the trade, how to simplify the lines, to insist on primary shapes, to exclude the unnecessary, all things that make stage design more effective. A great deal of this was already at his disposal because of Cubism. That’s why I was so keen to have late Cubist works opening the exhibition. In some sense, Cubism evolves into a vocabulary of shapes and forms that are articulated in space in such a playful way that Picasso could use that mechanism, that device, to articulate planes on a ballet or theater stage.

AmcdI’m curious how the exhibition is organized? Aside from the parameters of the time period, what other methodologies were applied to the curating?

OBWell, we have included two hundred works of art! It was important for me to tell the story of what happens between 1915 and 1925. The main thread of this vision has to do with Picasso’s stylistic changes, or more precisely, the back and forth he played with between different styles. Picasso was a very complex artist, he doesn’t give up Cubism; he keeps it alive. He used it within the framework of classical compositions and he switches back and forth between different modes of expression. To give you a very succinct example, Picasso loved Ingres’s portraiture. That particular tradition was used to create the famous portrait of Olga Khokhlova, from the collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris, Olga in an Armchair (1917). But then for the still lifes, he prefers to employ a Cubist or neo-Cubist mode. And, of course Picasso, in his earlier years, meaning the early 1900s in Paris, was very fond of street performers, of jugglers, of acrobats, the so-called saltimbanques. That is a world that he comes back to because of Parade, Cocteau’s fantasy about street performers.

AMcdWill visitors encounter the works in a chronological manner, or were the works arranged by some other method?

OBYes, we decided to have a somewhat chronological path whereby the story starts in 1915 and ends with The Three Dancers, of 1925. Overall it is chronological, but with groupings that are quite tight. For instance, there is a room of late Cubist paintings. Another room has a group of large bathers from the early 1920s, from the so-called Fontainebleau period, when he’s influenced by monumental forms and then creates big groups in a sculptural manner. And the interesting thing here is that Picasso doesn’t really sculpt in those years but the paintings convey a very solid feeling. That’s all on the ground floor, but then upstairs we document all the productions, not only Parade but the following ones like Cuadro Flamenco and Pulcinella, which is inspired by the Commedia dell’arte, and finally Mercure, which was not a Diaghilev production but one for a private French patron. Additionally, there are wonderful documents about Picasso’s trip to Italy, including nearly forty letters and postcards on loan from the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which have never been seen before.

AMcdThat sounds great. Will there be a book made for the show?

OBYes, certainly. At the moment it is only in Italian, but an English language version is forthcoming shortly, to be published by Skira.

AMcdGiven that this trip to Italy is when Picasso’s relationship with Olga begins, how much of this exhibition is a love story of sorts?

OBOlga is a very central character in this story, but I wanted to showcase her within the context of the Ballets Russes because after all, she was part of the theater company of Diaghilev. Interestingly, Olga is very often depicted in slightly melancholy poses, for example, in the show we have a drawing of Olga reading. However the backdrop is war. Her family is back in Russia, it’s the revolution, her father and her brother are members of the White Russian Army and she’s constantly given bad news, so she’s understandably anxious. Of course she is thrilled to meet the man she would marry, but she also has to struggle with the vagaries of war in her home country, in Russia and the Ukraine.

AMcdWar is the backdrop for the whole exhibition in some way.

OBYes, war is the backdrop for everything. In so many ways the art that is being created in 1917 in Rome is made by a group of people who are all displaced. And this is an aspect which I would love to focus on more in the future and eventually write something about.

All artwork © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY