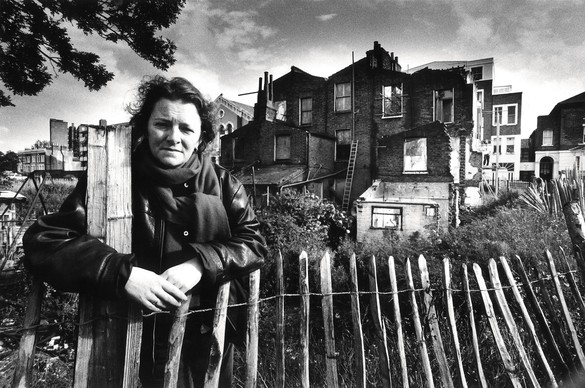

James Lawrence is a critic and historian of postwar and contemporary art. He is a frequent contributor to the Burlington Magazine and his writings appear in many gallery and museum publications around the world. Photo: William Davie

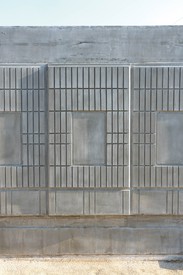

In June 2012, Rachel Whiteread unveiled her first permanent public commission in Britain. Tree of Life spreads across the upper façade of the Whitechapel Gallery, a venerable east-London institution with an important place in the history of postwar art. The façade had been incomplete since the Whitechapel’s opening, in 1901, when expected funds did not materialize, leading to the cancellation of a mosaic proposed for the wall’s central panel. Whiteread’s frieze elaborates on the building’s original terra-cotta reliefs depicting the Tree of Life, a motif that in the context of the Arts and Crafts movement of the time connoted social transformation through art. Leaves and branches of gilded bronze now punctuate the original areas of terra-cotta foliage, whose density anchors the sporadic distribution of Whiteread’s bronze elements across the central panel. The panel also holds four negative terra-cotta casts taken from the building’s windows. That kind of architectural reconfiguration established Whiteread in the public eye in the early 1990s, while her crisp vocabulary of everyday forms brought a new language to our private relationships with objects.

Tree of Life is insistently slight, influenced not only by gilded architectural grandeur but also by buddleia, an invasive plant that has thrived for decades in the crevices of London’s bricks and mortar. Pedestrians might easily miss the frieze as they hurry past with eyes on phones or traffic. There is power in its lack of clamor; sumptuously eye-catching, it nevertheless retains the flavor of an urban secret. Whiteread has spoken recently of “shy sculptures” such as Boathouse (2010), on the bank of a Norwegian fjord—sculptures that a viewer might encounter casually, sculptures that recede. We seldom attribute shyness to sculpture, particularly to sculpture such as Whiteread’s, which gives mass to intangibility. There has always been an unforthcoming aspect to her works, however, that incites us to fill their silences with our own reflections.

Whiteread’s breakthrough came with Ghost (1990), an assured realization of a deceptively straightforward idea. She cast the interior of a back room in a late-Victorian house slated for demolition. Nicotine stains and soot from the fireplace expressed the chemical history of the living space even as they tinted the sculpture’s plaster components. The result was bold but quiet, generously evocative, and clever in all the best ways. It earned Whiteread a nomination for the Turner Prize in 1991.

Ghost, like many of Whiteread’s early sculptures, relies on a crucial uncertainty or ambiguity regarding the definition of a given object. In particular, that ambiguity arises because of the way her sculptures challenge the natural flow of memory. When commentary on her work talks about memory, it usually explores aspects of the past such as history, nostalgia, remembrance, or commemoration. Those interpretations focus on what neuroscientists call explicit memory, which has two aspects: semantic memory, or the capacity for conscious recollection of common knowledge; and episodic memory, which preserves personal experiences. Implicit memories, which allow us to accomplish tasks without consciously thinking about them, are seldom discussed. Implicit memories allow us to type or write, drive a car, or deal with familiar objects. The unfamiliar familiarity of Whiteread’s sculptures often jolts such memories into our consciousness.

Whiteread’s methods excelled from the outset in prompting viewers to reassess, in a sustained and specific way, our relationships with the volumes and contours of our daily surroundings. Untitled (Torso) (1991), for example, gains an increasingly complex identity as we recognize how a modest hot-water bottle has become comfortingly pillowlike and newly corporeal. Before long, we readily attribute a self, or even a soul, to an inanimate object. Ghost embodied the empty space of a domestic room as an object in its own right, and so embodied an intuitive but rarely examined truth about how we actually occupy such spaces. Truths of that kind are at the heart of the recollections—unconscious or conscious, uniquely personal or held in common—that Whiteread’s sculptures invoke.

There has always been an unforthcoming aspect to her works that incites us to fill their silences with our own reflections.

James Lawrence

The path from Ghost to House (1993) was natural but far from straightforward. Whiteread was able to realize her idea of mummifying an entire house when the London organization Artangel, which commissions site-specific projects, invited a proposal from her. She and Artangel’s co-director James Lingwood scoured north and east London for a suitable site. The idea took shape on paper until, after false starts and much negotiation, Artangel secured a temporary lease on a house at 193 Grove Road, in the East End neighborhood of Bow. That house—a very short walk from the Chisenhale Gallery, where Ghost had made its public debut—was part of a Victorian terrace destined to yield its ground to a modest increase in local green space. The house had been occupied for more than fifty years by the last resident of the terrace to resist the inevitable.

House was a masterpiece: ambitious, audacious, and a clear demonstration of Whiteread’s place among the elite of postwar sculptors. That much is clear today, nearly twenty-five years later. At the time, the project was traumatic and contentious. The informed and respectful criticism that it prompted only inflamed tabloid scorn and hardened the intransigence of a pivotal local politician. When Whiteread won the Turner Prize for 1993, the announcement occurred on the day that House failed to win a reprieve from demolition.

House is now something of a legend. It attracted thousands of visitors during its few months of existence, garnered support in the House of Commons, and heralded a resurgence in British art that soon transformed the cultural landscape. Though House is lost, its spirit endures in its historical significance and in the aesthetic terms it validated. The sculpture’s equipoise of imposing monumentality and innate pathos—the vulnerable isolation of a terraced house alone at the edge of a field—remains central to Whiteread’s public commissions, including Cabin (2016), on Governors Island, New York.

Implicit memories allow us to type or write, drive a car, or deal with familiar objects. The unfamiliar familiarity of Whiteread’s sculptures often jolts such memories into our consciousness.

James Lawrence

The heft of interior voids converted into concrete masses, and Whiteread’s aptitude for reconfiguring architecture, inevitably prompted comparisons with a primarily American lineage of sculpture since the late 1960s that includes works by Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Eva Hesse. Whiteread’s sculptures, however, also warrant consideration as part of a much longer tradition in which the texture of history—and, crucially, the way we use history—are inseparable from the objects’ material forms. In 2003, Whiteread cast the interior of Room 101 in Broadcasting House, the British Broadcasting Corporation’s flagship building in central London. A popular belief holds that George Orwell got the idea for the torture chamber in his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), also called Room 101, from his miserable period of employment at the BBC during World War II. In fact, Orwell’s Room 101 was in another building nearby. The discrepancy between irresistible myth and Whiteread’s robust translation of material facts added an additional note of complexity appropriate to the uncertainties of history. When Untitled (Room 101) was exhibited in the Cast Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum, it seemed incongruous yet thoroughly at home—anachronistic yet among similarly displaced friends. Unfamiliar familiarity is not merely a phenomenon of memory prompting us toward introspection, it also reveals something about how we weave the past into the ever unfolding present.

Ghost, House, and Untitled (Room 101) all involve pragmatic and almost photographic translations of reality into representation. The result is a kind of nakedness. All three sculptures, after all, were or are public revelations of private space. Even the room in Broadcasting House that Whiteread cast served the plumbing and ventilation needs of the building rather than the purposes of the BBC as an organization. Much of the pathos of House stems from the rapidity with which the building lost its claims to privacy and became a public figure—a process that also claimed Whiteread herself as she made and defended her work. Despite the formal consistency of her practices, there is a significant difference between that transition from private to public, on the one hand, and avowedly public projects on the other.

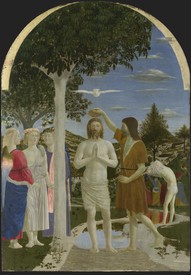

Holocaust Memorial (2000) was from its inception a public work inseparable from the purposes of acknowledgment and atonement for crimes against humanity that occurred in living memory. Those crimes against humanity included countless crimes against individuals, as well as acts that destroyed the accumulated material conditions of lives, communities, and relationships. Whiteread’s memorial to the 65,000 Austrian Jews murdered during the Holocaust stands in Vienna’s Judenplatz, surrounded by dignified residences. Although her design called for an invented space from the outset, it is no great leap to imagine—as Whiteread did—that it originated in an apartment just yards away. Its cuboid form, with somber ranks of books on shelves and double doors forever closed, implies a private library turned inside-out even as it occupies public space with the dignity of a cenotaph. Whiteread’s “nameless library” of books with no spines visible allowed her established techniques to quicken a concise symbol of culture, memory, loss, and private individuality within the public realm. The books allude to the textual tradition of Judaism, but inevitably connote Nazi biblioclasm as well as more benign associations. More poignantly, they are ciphers of lost lives that were biographical as well as biological—reminders that private accounts of those losses remain unwritten, or closed to history.

Holocaust Memorial, Whiteread’s first permanent installation, remains exceptional for its combination of permanence and high-profile location. She is selective in her choice of commissions, and skeptical of ill-judged impositions of sculpture in public spaces; despite their physical and philosophical weight, her public sculptures have typically been elusive and even self-effacing. In 1994, soon after House was demolished, New York’s Public Art Fund invited Whiteread to devise a work. Grand locations did not appeal, but, scanning Manhattan with a visitor’s keen eye, she noted the wooden water towers that punctuate the skyline and stubbornly preserve a nineteenth-century sense of place. She eventually found an old water tower to use as a cast, as well as a site for the installation. Water Tower (1998) stood on a roof in SoHo for just over two years before finding a new home on the roof of the Museum of Modern Art.

Whiteread has been working with resin since the early 1990s. She quickly grasped the potential of that tricky material, including ways to produce color variations by blending different types, as in Untitled (One Hundred Spaces) (1995). She found that resin can remain translucent, even transparent, in deep and massive forms. Water Tower is a four-and-a-half-ton cast in polyurethane resin. Its clarity was a formal innovation for Whiteread, whose previous large-scale sculptures had arrested space in a state of opacity. One consequence of this extended vocabulary was a valuable complication of the metaphysical themes, usually morbid, that circled her work. Another consequence was a new kind of reticence: dematerialization. Water Tower can seem crystalline, fluid, or ethereal, according to viewing position and prevailing light. Those transitions have an underlying material logic: resin never quite suppresses its liquid past the way plaster and concrete do, or the way igneous rock does. Visual uncertainty attends Water Tower not because its contours are counterintuitive but because its material state seems unfixed. It is persistently elusive because physical distance from street level limits proximity and precludes contact. We recognize the form without truly knowing the content.

Whether we consider the placement of Water Tower, the elegiac murmur of Holocaust Memorial, or the unelaborated statement that was House, Whiteread’s public sculptures have always embraced the power of reticence. Monument (2001), her contribution to the series of temporary projects for the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square, involved a direct cast from Sir Charles Barry’s unoccupied granite plinth, built in 1841 to support an equestrian statue, of King William IV, that never came. Monument was a formidably challenging exercise in fabrication that strove for the appearance of effortlessness. The result had complex semiotic relationships with Barry’s plinth, Trafalgar Square, and the metropolitan residue of imperial might, yet it declined to make those relationships explicit. The two-piece resin cast was an apt tautology that mirrored the past, shimmered in the present, and anticipated no future. It got to the heart of the Fourth Plinth project with the unembellished completeness that characterizes Whiteread’s casts. As in Tree of Life, Whiteread’s approach to the Fourth Plinth addressed an existing incompleteness: just as lack of funds had left the facade of the Whitechapel Gallery without a mosaic, so lack of funds had left Barry’s plinth without its anticipated statue. Whiteread responded to both situations with generous acts of formal reconciliation that bridged centuries without suppressing the unresolved conditions that had made her involvement possible.

An encounter with one of Whiteread’s works in public is comparatively rare. Where they are permanent, they are often inaccessible or easily overlooked. Her temporary projects pass into episodic memory, where they gain their own uncertainties. For busy Londoners who passed House, and glimpsed a familiar building in an unfamiliar form, the memory might today have become a pale shadow, perhaps refreshed by photographic reinforcement. Whether they are unavailable except as memories and photographs, or merely situated away from our habitual lines of sight and movement, Whiteread’s public sculptures retain irreducibly private aspects. They suggest rather than state, imply rather than impose. For the viewer, those are not easy or rapid conditions of engagement: shyness can be unfathomable. It can also lead us to moments of profound empathic intimacy.

Artwork © Rachel Whiteread