Let the insanity play itself out through the materials. Then you don’t have to worry about style. You’ll just be working to describe your own insanity.

—John Chamberlain

Gagosian is pleased to present rarely seen sculptures by John Chamberlain. Following the New York showings of New Sculpture at Gagosian in 2011, as well as Choices, his 2012 retrospective at the Guggenheim, the current exhibition highlights a series of steel masks, the majority of which are on view for the first time since their creation in the 1990s, as well as abstract wall sculptures made between the 1970s and 2000s.

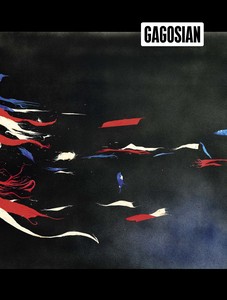

Best known during his lifetime for his distinctive metal sculptures, often made of crushed and torqued automobile steel, Chamberlain used the detritus of American industry to create works that contain the bold energy of Abstract Expressionism, the premanufactured elements of Pop and Minimalism, and even the provocative curves and swells of the High Baroque. His multidimensional collages of foam, steel, or aluminum—from large floor sculptures to more intimate interlocking arrangements—express an unwavering elegance, exuding both the strength and the fragility of everyday materials.

From the beginning of his career, Chamberlain emphasized the primary role of abstraction in his work. In 1991, he turned to a more recognizable form: the mask. Assembling intricately cut, painted metal parts, he made his first mask, A Good Head and a Half (1991), for a benefit auction for Victim Services, providing aid to victims of sexual assault. He continued to produce masks throughout the 1990s in his studio on Shelter Island, titling many of them with opus numbers—as in Opus 16 (1998) and Opus 90 (1998)—thus aligning their visual dynamism with the various synchronized elements of a musical composition. Similar to the Tonk sculptures that precede them, which were made of disassembled toy trucks gathered from an abandoned Tonka Toy factory in 1981, the masks possess a vibrant, lyrical innocence, with their overlapping strips and shards of metal, as well as nails, used to evoke hair, beards, eyebrows, teeth, and crowns.

Complex relationships between color, texture, and form are found in both the masks and the wall sculptures. Cum Two Me (1977) is a multicolored mass of curved and conjoined steel scraps, combining raw, rusty edges with straight lines, and spray-paint drips with polished chrome. These juxtapositions are echoed in THE MASK OF PERSISTENCE (1996), with its protruding tongue and spirals of hair, which emerge from behind leaflike planes of white and red. In Rebel Ruckus (1975), the twists and folds of the metal resemble crumpled paper in hues of pink, green, yellow, and blue. With its various ridges and cast shadows, the abstract sculpture tempts a search for the contours of a face, yet remains undefinable, exemplifying the subtle anthropomorphism of Chamberlain’s abstraction. This ambiguity can be found in the masks as well; though they are representational in nature, they too are comprised of interconnected abstract units.