Wyatt Allgeier is a writer and an editor for Gagosian Quarterly. He lives and works in New York City.

Betty Parsons wasn’t an extraordinary businessperson. She spent little time thinking about profits: “I’ve always been given the vision to be ahead,” she said. “I never made money because I saw things too far in advance.”1 Asked about this in 1979, three years before her death, Parsons succinctly quipped, “I was interested in creation.”2 The great art dealer Leo Castelli commented, “One couldn’t be a Betty Parsons and at the same time be a good businesswoman. She was much too . . . poetic for that.”3 He added, “It was the beginning of a great moment in American art that started there at Betty Parsons’s. For the first time a great original art movement took place in America.”4 At the Betty Parsons Gallery, the pursuit of financial gain took the back burner to the work of establishing America as a player in the world of art. In notes now housed at the Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, Parsons wrote, “The business of art is a tyranny of forms and finances. I like the creative aspect and the recognition . . . but the business of it is less interesting to me—God knows you must cope with it.”5

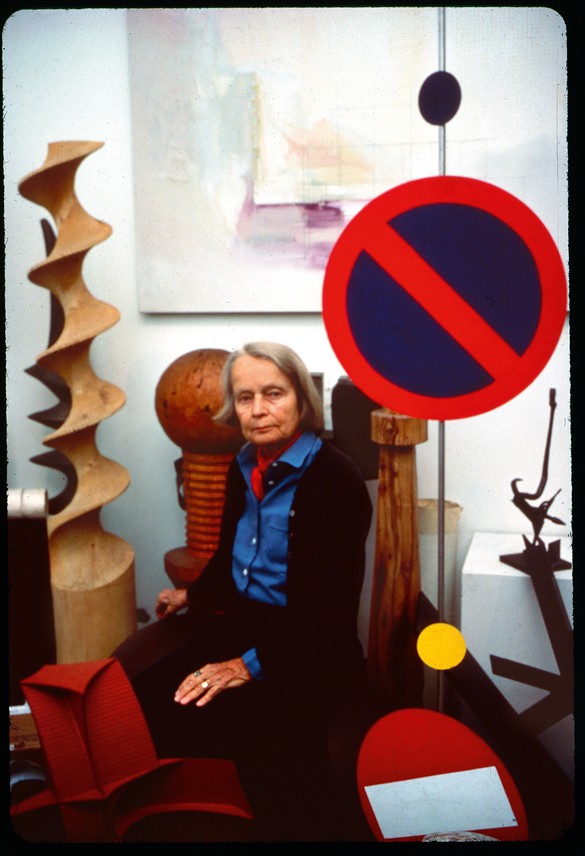

And, begrudgingly, she did. In the nearly four decades of the gallery’s existence, from 1946, when she opened her doors with a $5,000 loan from various friends, until 1982, Parsons did sell art. After all, operations on 59th Street had to continue until they couldn’t: “I’ll probably die in my gallery in the middle of hanging a new show.”6 With its innovations in presenting the most vigorous artists across America, the gallery was part of Parsons’s raison d’être. So was her own artwork: sublime sculptures made from driftwood painted in rich patterns, and paintings with an aerial appreciation of expanse. All of these practices shared their root in passions ignited by Parsons’s visit to the historic Armory Show of 1913, when she herself was thirteen. An origin story as concrete and revelatory as any biographer could dream. For the woman who fostered the careers of Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Ellsworth Kelly, Adolph Gottlieb, Forrest Bess, and Agnes Martin (the list continues, but let this sample suffice) to have attended, and at a formative age, the exhibition that debuted the European avant-garde in the United States ties together the narrative strings of Parsons’s life: risk, unremitting commitment to the future, a full-throated defense of a liberatory art, and more. “I felt like those paintings . . .” she would recall. “I couldn’t explain it, but I decided then that this was the world I wanted . . . art.”7

I don’t feel that by doing this that I am carrying a special torch—this freedom of the spirit has always existed, and my devotion to it and presentation of it to the public is a simple human act, and all I am asking of the public is to come.

Betty Parsons

This cornerstone moment in Parsons’s life is joined by another, a near cosmological spark for her championing of an American abstract art. It took place at a rodeo: “I saw all the movement, the noise, the color, the excitement, the passion. I thought, my God, how can you ever capture this except in an abstract sense?”8 That this vision in the American West receives more attention in her own telling of her life than her time studying sculpture at the Grande Chaumière, Paris, with Alberto Giacometti and Isamu Noguchi, attests to her idiosyncratic focus.

While biographers have these foundations to build on, the sheer grandness and scope of Parsons’s achievements aren’t so easily accounted for. A consequential exhibition experience as a teen and a visionary scene of bull-riders doesn’t necessarily result, after all, in being able to “construct the center of the art world,” a feat Helen Frankenthaler retrospectively attributed to her.9 Maybe her daring in displaying art denounced at the time as “perverting the public taste,” according to Ken Kelley in People in 1978, maintained its conviction because she had found herself outcast from her early life, as a child of a wealthy New York family, due to her intellect, drive, bisexuality, and independence.10 The credit for her longevity might have been raised in the cradle of humility: “I don’t feel that by doing this that I am carrying a special torch—this freedom of the spirit has always existed, and my devotion to it and presentation of it to the public is a simple human act, and all I am asking of the public is to come.”11 Or perhaps her unquenchable thirst for the unconventional, the misunderstood, the risky grasp toward the unseen, was forged through a recurring abandonment by others. Many of the artists whose careers she cultivated would later abandon her for the greener pastures of some more fiscally secure dealer. (Artists too have bills.) Perhaps her singular ability to discover and foster budding artists was rooted in her being an artist herself. Or maybe it was as simple as the conversation recounted in Kelley’s profile of her: “A very famous artist once asked me, ‘How do you do it?’ I told him I was born with a great love of the unfamiliar.”12 When a person can’t be sated by what’s known, how much can she discover?

Whatever the sources of her accomplishments, the result remains the same: Betty Parsons transformed what the world conceives of as art. All those who find themselves transfixed before the pulsing colors of Rothko, the symphonic vibrations of Pollock, the mystical unsettlement of Bess, the supremely confident line of Newman, and the quiet security of Martin owe a moment of homage to the incredible woman who, against so many odds and so much hostility, presented their works for anyone brave enough to come. And may we, with as much dedication as we can muster, hope that more like her will break through and fight for so little reward: “These artists are establishing a relationship with the world through their own experience, and I have made a place where their expression can exist. That the strength of this liberation is so important, so vital, in a world where we see freedom being submerged all around us, is adequate compensation for my commitment.”13

1Betty Parsons, quoted in Grace Glueck, “Betty Parsons the Art Dealer’s Art Dealer,” Ms., February 1976, p. 109.

2Parsons, quoted in Grace Lichtenstein, “Betty Parsons: Still trying to find the creative world in everything,” Artnews, March 1979, p. 56.

3Leo Castelli, quoted in Carol Strickland, “Betty Parsons’s 2 Lives: She Was Artist, Too,” New York Times, June 28, 1992. Available online at https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/28/nyregion/betty-parsons-s-2-lives-she-was-artist-too.html (accessed July 18, 2019).

4Ibid.

5Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, c. 1920–91, box 39, folder 5: Artist Biography and Narratives, series 7, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC. Available online at www.aaa.si.edu/collections/betty-parsons-gallery-records-and-personal-papers-7211/subseries-7-2/box-39-folder-5 (accessed July 22, 2019).

6Parsons, quoted in Ken Kelley, “Betty Parsons Taught America to Appreciate What It Once Called ‘Trash’: Abstract Art,” People, February 1978, p. 85.

7Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, c. 1920–91, box 39, folder 5: Artist Biography and Narratives, series 7, Archives of American Art. Available online at www.aaa.si.edu/collections/betty-parsons-gallery-records-and-personal-papers-7211/subseries-7-2/box-39-folder-5 (accessed July 22, 2019).

8Parsons, quoted in Kelley, “Betty Parsons Taught America,” p. 78.

9Helen Frankenthaler, quoted in Strickland, “Betty Parsons’s 2 Lives.”

10Kelley, “Betty Parsons Taught America,” p. 76.

11Parsons, in “Interview over WNYC Art Festival,” October 16, 1951. Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, c. 1920–91, box 39, folder 7: Interview—WNYC (Radio Station) Art Festival, October 16, 1951, Archives of American Art. Available online at www.aaa.si.edu/collections/betty-parsons-gallery-records-and-personal-papers-7211/subseries-7-2/box-39-folder-7 (accessed July 22, 2019).

12Parsons, quoted in Kelley, “Betty Parsons Taught America,” p. 85.

13Parsons, in “Interview over WNYC Art Festival.”