Dr. Ziba Ardalan is the founder and artistic and executive director of Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art, an art institution and educational charity established in London in 2004. A graduate of Columbia University, Ardalan served as the first director/curator of the Swiss Institute in New York. Prior to a career in art, Ardalan obtained a PhD in physical chemistry.

Independent curator, author, and art advisor Elena Geuna has curated exhibitions internationally, including two on Lucio Fontana, one at the Palazzo Ducale, Genoa (2008), the other at MAMM, Moscow (2019).

Kay Pallister joined Gagosian in New York in 1997. With a postgraduate degree in curatorial practice from De Appel, Amsterdam, she has worked with several artists on exhibitions, productions, public artworks, and publications for more than twenty years, both within the gallery and with nonprofit organizations. She is currently working on a monograph devoted to the work of Richard Wright.

Kay Pallister So, first of all, I wanted to ask: When did you first encounter the work of Y.Z. Kami? Where was it, and how did you come about it?

Elena Geuna The first time I saw Kami’s work was at Jeffrey Deitch’s space downtown—I think it was in the late ’90s. I saw this installation of photographs and portraits, and it was quite surprising, because I didn’t know the artist, and I was fascinated by the juxtaposition of architectural photographs and portraits. It was a work called Dry Land that has since been exhibited in various museums worldwide.

And then after a few years I encountered Kami’s work again, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York: two monumental, mysterious—but at the same time extremely enticing and modest—portraits in a group show called Without Boundary. Those monumental portraits were juxtaposed with two small screens by Bill Viola. The spirituality and devotional spirit of this room made me spend time with, and try to perceive more from, these wonderful portraits.

Later on I saw the wonderful show that Ziba curated at Parasol Unit in 2008. Kami’s show there was the first monographic show that I had seen, and it was a real discovery. Since then I’ve visited the studio repeatedly, and I’ve been really touched by his work.

KP And Ziba, how did you come across the work before you exhibited it?

Ziba ArdalanI met Kami during the Venice Biennale that Robert Storr curated in 2007. We started talking, and I asked him to do the exhibition at Parasol, which was a wonderful collaboration.

KP Can I ask you about the works you chose to exhibit in Venice in The Spark Is You [The Spark Is You: Parasol unit in Venice, May 9–November 23, 2019]? What did Kami’s work bring to the concept you had for this group?

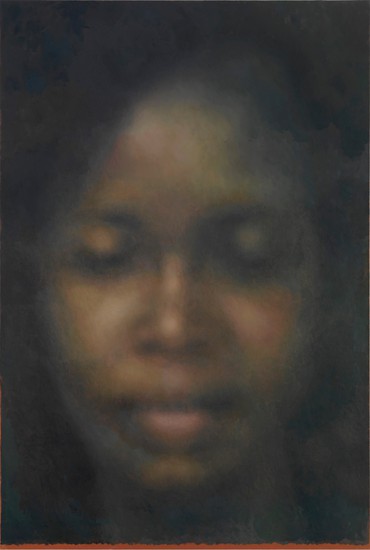

ZA Well, The Spark Is You is my response to coming home after many years. The works are all conceptual, and I invited Kami because his work is so ambiguous in feeling. They are not straightforward portraits: they are not psychological; they don’t offer a photographic memory of the sitter. If the subjects are looking at you, you go close to them, but as you do, the image dissolves. So there is this incredible lack of accessibility to the work, to the sitter. They all have double meanings, double edges.

I have the feeling that a lot of Kami’s work is really rooted in meditation. there is an essence in the work which is free of time.

Kay Pallister

KP I have the feeling that a lot of Kami’s work is really rooted in meditation. There is an essence in the work which is free of time. I wonder if you could talk a little about this. You said something very interesting earlier, which would be lovely to hear more about: the idea and experience of looking at portraits when it’s clear that they’re from another era but they seem timeless. I know we can’t tell what people will feel looking at Kami’s work hundreds of years from now, but I wonder if they will still seem so free of time, and ultimately contemporary, at any moment.

EG After Kami and I started to work together on an interview for the book, we spent time visiting museums together during my stay in New York. One of the first visits we did was to the Met, and it was interesting to see that we’d stop in front of the same paintings, and one of the paintings was a late self-portrait by Rembrandt. Rembrandt self-portraits are timeless, but at the same time they represent their time, you know? Rembrandt was at once approaching the issue of himself as a sitter and the context of the world he was living in.

And I think in a way, Kami’s practice—being so personally rooted in both his Eastern past and his time spent in the Western world, studying philosophy in Paris—has allowed him to make visible what’s invisible. I think of the quality of the paintings that Ziba was talking about before; his portraits challenge you, they ask you to spend time in front of them, to try to understand them. They often have their eyes closed, and if you get closer, they become completely abstract. I think that this characteristic makes them even more intriguing and, yes, timeless.

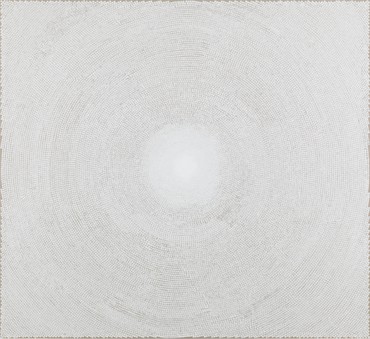

ZA One of the elements that makes the work timeless is visual stillness. This comes, in part, from the modified oil paint that Kami uses; that very matte surface creates a sense of stillness. There is a spirituality in his paintings. Whether they are portraits, whether they are Dome paintings, they are basically one thing; I don’t see a difference between them. And when I look at Kami’s incredible painting—that Black Dome, or the Gold Dome—it’s spiritual. For me that is Kami’s farr, or as they would say in Zoroastrianism, faravahar—divine glory. As you know, much of our culture and tradition in Iran comes from Zoroastrianism.

KPIt’s interesting, because what you’re talking about is free of a belief system, in a way. It doesn’t matter which belief system any of us holds.

ZAExactly.

KPIt’s free of illustration, of something that is pretending to look like something else. The works are very elemental. While we’re reflecting on the Dome works, they seem to be built, for the most part, with brick-shaped pigment blocks that must be composed over a long time—a very rigorous process. And I know that Kami has made works that reflect quite literally on architecture of the past, using photographic references, but I wonder if you feel that these particular works, the Dome paintings, have a significant relationship to architecture or if this is only incidental while he formally builds the whole surface of the painting?

EGWhen I was asking Kami this question, he explained that he had seen the circular form in temples, in churches, in Persia, in Byzantium, in Italy, and that this had stayed with him, becoming the source of inspiration behind some of these works. Architecture, I think, has been an influence from the beginning, together with what Ziba was explaining just now. And this circular form of the temple, in a way, leads to abstraction. It starts from black, from the nigredo, and he moves on to white, blue, which is the color of heaven, to end up in gold, which is the sacred color.

Talking about beliefs, In Jerusalem, the work that he showed at the Venice Biennale, is a fabulous installation of five small paintings of religious leaders. It’s unique in his practice, but it goes back to what you were saying—

ZALack of tolerance is basically the subject of that painting, isn’t it?

EGYes.

KPYes. The images, I understand, came from a New York Times article.

ZABasically, the leaders of different religions go to Jerusalem to forbid or criticize a gay parade or something—when you take that out of the world, according to Kami, it’s burning with a lot of other issues.

EGIt was quite surprising that the only way they could come together was against a gay pride manifestation—

KPIntolerance united—

EGIntolerance, absolutely. And, at the same time, Kami is able to portray the leaders—two are Jewish, one is Muslim, one is Catholic, one is Christian Orthodox—without passing judgment. He leaves it to us to decide.

KP I think of this work as an exception to his usual portraiture, as one can pinpoint the subjects in a specific cultural context. I think for the most part the portraits are much more ambiguous: you might glean vaguely how old the subjects are, or potentially what ethnicity, let’s say, but you are left to contemplate and experience a kind of aura of the person, rather than something more specific.

So, I wonder if I could ask you also about the figures, whether their identities are important. Quite often they are without a title or a name—

EG In my mind, the anonymity is an important part of Kami’s portraits, because he is able to create a sense of collective humanity through a series of portraits or even in a single portrait. These portraits are not about the face, but about the aura, as you were saying. You can perceive a kind of devotion from the portrait.

KP I think the act of painting a portrait for any artist is an act of homage to that person. It’s almost the opposite of taking a photograph, which is a moment of capture—it’s a different, intensive labor of looking.

I wonder if you have had a chance to see the very final images in the book, which are called Night Paintings, and what you might think about this new work?

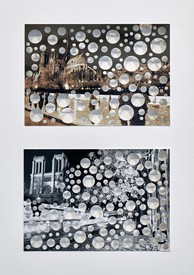

ZA I have the impression that over time Kami’s paintings of people have become more and more dematerialized; the faces are much more dematerialized than, say, fifteen years ago. I think this is an incredible phenomenon, and this leads right up to the Night Paintings. Considering he brought dematerialization to the human face, why not go one step further? The Night Paintings are abstract works which are almost like beautiful hallucinations.

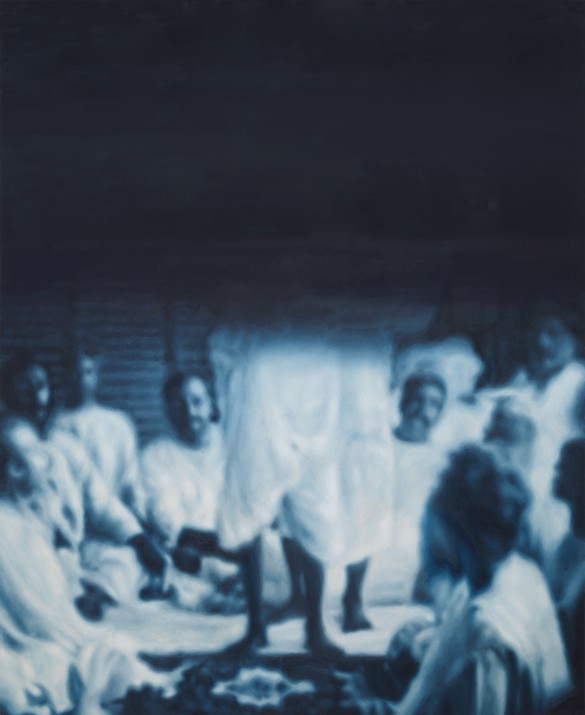

EG Abstraction and figuration with Kami have always lived together—a little bit in his early work, and as you said, much more so in the most recent work. When I first saw the Night Paintings in person, I was quite surprised, because one of the two Night Paintings has suggestions of human figures, but without faces, while the other is completely abstract.

I think it will be very exciting for all of us to see the new paintings that Kami is not revealing anything about and that will be shown in Rome [in early 2020]. Maybe they’re going to be abstract, maybe they’re going to have faces again, but I think that abstraction and figuration have cohabitated very well in the artist’s practice through time.

Y.Z. Kami: Night Paintings, Gagosian, Rome, January 18–March 21, 2020

Artwork © Y.Z. Kami