Independent curator, author, and art advisor Elena Geuna has curated exhibitions internationally, including two on Lucio Fontana, one at the Palazzo Ducale, Genoa (2008), the other at MAMM, Moscow (2019).

Y.Z. Kami was born in Tehran. He lives and works in New York. His work reflects a diverse range of interests, from portraiture to architecture, from photography to sacred and literary texts. Kami’s work has been featured in public collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the British Museum, London; and many other institutions worldwide.

Elena GeunaI remember first seeing your work at Deitch Projects in New York in the late ’90s—an installation entitled Dry Land, which coupled photographic works with painted portraits. And I remember first having a sense of discovering, of being taken by your work a few years later, in 2006, at the exhibition Without Boundary at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. I was mesmerized by the sheer monumentality of the sitters—one male and one female—in the paintings, which were juxtaposed with a small screen by Bill Viola. To me, their spirituality was palpable, as if emanating from the work itself.

Y.Z. KamiThis was the first time I painted figures with their eyes closed or completely lowered. It was a very new experience for me. I had always painted faces with eyes looking directly at the viewer—this was the first time the gaze was not there. It was absent. You see, when the eyes look outward, they become the center of the painting. With the eyes closed, the whole surface of the face is the focal point.

EGWhat is it about the human face that makes you want to paint it?

YZKFor me, to paint is essentially to paint faces. Although I also do other things, no subject matter captivates me as much as the human face does.

EGThere is something arresting about your portraits. One can’t help but be transfixed by them. Do you remember when you first became interested in painting portraits?

YZK As far as I remember, my only interest was to paint faces and to paint them with oil. I started to paint from an early age, around five or six years old. My mother had been a painter and her studio was in the family home in Tehran. Sometimes I would paint there with her. Her style was sort of academic—portraiture, landscapes, still lives, and also copies of the old masters. I have several of her works—they are very well painted. For a number of years, she worked at Ali Mohammad Heydarian’s [1896–1990] studio, painting under his guidance. I recall accompanying her there as a child and hanging out for hours. By that time, he was an old man. I was fascinated with the number of paintings on the floor leaning against the wall. He came from a generation of Persian painters who traveled to Europe in the 1920s and ’30s to look at old master paintings in European museums. He painted in a very nineteenth-century academic style, occasionally with Persian subject matters.

EGCopying artworks, especially old master paintings, was part of your formative experience. Do you remember which was the first?

YZKI think it was Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus. I copied it from a small photograph in an art history book. Years later, I saw the real painting at the National Gallery in London. It is an exquisite painting—the shape of the body and the color of the skin are amazing. The lightness of the brushstrokes, the way the feathers on Cupid’s wings are painted . . .

EGI understand that you went to Paris to study philosophy after finishing high school in Iran.

YZKWhen I left Iran, I didn’t want to become a painter. Painting was the past—it was my mother! I was very much drawn toward literature and the humanities. Paris was very interesting in those fields in the mid- to late ’70s. I remember attending Emmanuel Levinas’s philosophy classes at the Sorbonne. Henry Corbin was at l’École des Hautes Études, where he gave seminars on Sohravardi, the twelfth-century Persian philosopher and mystic. Roland Barthes and Lévi-Strauss were giving lectures at the Collège de France. I remember one year in the late ’70s following Barthes’s talks on Proust and photography. It was a very interesting era. But, after several years, I realized that I didn’t want to teach, and I cannot write really. . . . For a couple of years, I also studied film, and I saw that film is a collective work and I am a solitary person. So finally, after several years, I went back to painting.

EGIt is interesting how you have bridged Western traditions and aspects of your Persian heritage.

YZKSince childhood, I was exposed to both Western and Near Eastern influences. I was very connected to Persian poetry and also architecture at the time—less so to the visual arts or Persian miniatures, though. My interest in painting was with the European masters, which I guess most probably came from my passion for oil paint, and oil paint was invented in Europe.

EG Who are your favorite Persian poets?

YZKHafez and Rumi are my favorites, although there are other great poets. I always read their poetry and read them in Persian—for me Hafez gets totally destroyed in translation. I don’t know how Goethe loved him so much, given he only read translations—unless one can say that great poets are able to communicate on different levels!

EGSpeaking of old masters, I would like to talk about Piero della Francesca’s Madonna della Misericordia, in which the Virgin is portrayed with her head and gaze directed downward.

YZKThe gaze is downward and the head of the Virgin is almost a perfect circle. The balance, the geometry, the stillness . . . the silence in his work is incredible. Also, his Madonna del Parto . . . It might seem a little bizarre but I somehow sense similarities between Piero and Morandi!

EGHow did you come to the name Y.Z. Kami?

YZKKami is my nickname and I have always loved names with initials in them, like those of some of my favorite poets, C. P. Cavafy, the Greek poet of Alexandria, W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot . . . Y.Z. stands for Youssefzadeh.

EGAnd this came about after you arrived in New York, in 1984. It was in the years following your arrival, after a trip back to Iran, that you began to work on the Self-Portrait as a Child series.

YZKOn that trip, I came across a photograph of myself as a child. I must have been around ten years old or so when the picture was taken. I brought it back to New York with me. For several years, I worked on a series of drawings and paintings based on that photograph.

EGMost of the Self-Portrait as a Child series consists solely of the image of you as a child. However, in one of the paintings from the series—the one in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum—your image is somehow inserted into a setting with other people, which is quite intriguing. Three women are sitting around a table, in what looks like a formal setting, with your image painted over part of the painting.

YZKIt seems like the women are having tea. . . . It could be the setting of a Chekhov play.

EGAfter this series of self-portraits, there have not been any until recently.

YZKYes.

EGIn fact, I have seen the self-portrait that was recently exhibited at Gagosian in Paris. I found it quite haunting. Did you paint it in your studio in New York City or in your studios upstate in Garrison, New York, in the countryside?

YZKI painted it in Garrison. It is the only portrait that I’ve done of myself as an adult. I always felt a bit camera-shy and somehow too inhibited to paint myself. Then last year, all of a sudden, I started to paint this self-portrait. It became very fuzzy . . . sort of strange. But when I saw it installed in the show in Paris, I actually liked it.

EGSeeing your studios in Garrison was a fascinating experience. There was so much light. And it felt so intimate at the same time. Maybe in Garrison you encounter less intrusion on your privacy than in New York, where people often visit.

YZKIn the countryside one is less interrupted. Especially where I have my studio, which is far removed from everything and in the middle of nature.

EGI remember discussing self-portraiture with you when we went to the Metropolitan Museum together the last time I was in New York. We were looking at the Rembrandts.

YZKThey are extraordinary—the late self-portraits.

when the eyes look outward, they become the center of the painting. With the eyes closed, the whole surface of the face is the focal point.

Y.Z. Kami

EGRegarding the evolution of your work in the late ’90s, you did a piece that comprises a series of paintings. It is called Untitled (16 Portraits) and now belongs to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Who were the sitters?

YZKA group of ordinary people . . . friends and strangers that I asked to sit for me. Just human beings.

EGIs anonymity an important component?

YZK Yes, it could be important in this work. It does have a vague reference to Fayum portraits. You know, the Fayums were painted of specific people for a specific purpose, but, with the passage of time, they have become anonymous.

EGWhen did you first become aware of Fayum portraits?

YZKI saw them for the first time at the Louvre when I was a student in Paris. I was about twenty years old. The Louvre has a great collection of Fayum paintings. I was very taken in. Ever since, I continue to look at them. There are also beautiful ones at the Metropolitan Museum, at the Pushkin in Moscow, and at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

EGI recently saw some fantastic ones at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. It is interesting to look at these portraits knowing they were made when the subjects were alive but were meant to be used after they passed away.

YZKThey were meant to be for eternity—that’s why they were made with encaustic. They were buried with the body. The eyes are very stylized, very large. . . . They are the most important part and the center point of the painting.

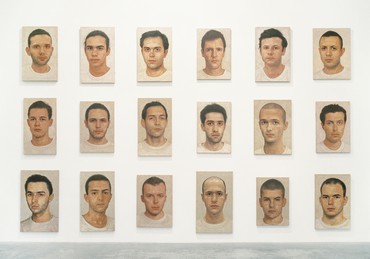

EG Prior to Untitled (16 Portraits), you had done another large work called Untitled (18 Portraits).

YZKThe sitters of the Untitled (18 Portraits) are all men, rather young men. The work has a funerary mood, and is a direct reference to the Fayum paintings. The portraits were painted around 1994–95, at the height of AIDS in New York. So many young men were dying. It was devastating. There has been a misconception that the sitters in this work had the disease but this is completely incorrect. There wasn’t anything biographical about the sitters at all. For me, the work is an elegy for that time.

EGAfter this work, you started to concentrate on individual portraits rather than group portraits. If we look at portraiture throughout history, it is one of the oldest and most significant art forms. Each era has approached it in its own unique way. Today, for example, digital devices hold a monopoly on portraiture. Your portraits, on the other hand, seem to look back on a previous era. What does portraiture mean to you, especially today?

YZKThe human face is an endless subject for painting. Portraiture, before the invention of photography, was different. In the nineteenth century, we started to have the influence of photography, even on Ingres and later on Degas. I think there is a “before photography” and an “after photography.” Then the digital age, as you said, has come, with Photoshop and the use of technology in the manipulation of images.

EGYour portraits seem to present the inner subject. There is a sense of truthfulness that goes beyond the face toward the soul, the aura.

YZKThat’s what you see! I hope you’re right, though I cannot generalize. I think when one starts to paint, one is just carried away with the work. I don’t start a painting with any strategy or plan in mind. The painting takes me where it wants to go.

EGI cannot forget the first time I saw In Jerusalem in your studio; you were working on it at the time. It was a very powerful experience. Could you tell me about the work?

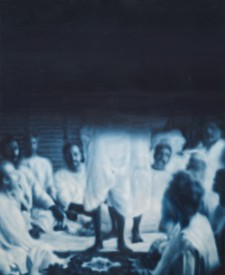

YZKOn the morning of March 31, 2005, I opened the New York Times and saw a picture of a gathering in Jerusalem of clerics from the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The purpose of the gathering was to prevent the gay festival from happening there. I was so shocked that at the height of the Iraq war and when so many horrible things were happening in that part of the world, these clerics should come together just to prevent a gay festival from taking place! Intolerance is something that they all agreed upon and shared. I remember that as I saw the picture in the newspaper, I saw a painting . . .

EGThe interesting thing is that you didn’t create a single painting but separate canvases. You also worked on a preparatory sketch.

YZKYes. After I saw the newspaper, I first worked on a preparatory sketch. I decided to choose different canvases of different sizes for each of the figures. The result was a painting in five pieces.

EGWorks of this kind are quite unique; it is something that came about because of the image you saw in the New York Times.

YZKYes, that’s right.

EGIn the Endless Prayers series, different sacred sources are being represented.

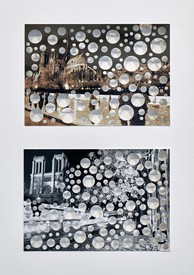

YZKThe composition in the Endless Prayers series, and in the Dome paintings, comes from the concentric forms of domes that I had first seen in Persian architecture as a teenager, and later saw in Byzantine churches and basilicas. The dome is like a metaphor for the heavens . . . the idea of temple and contemplation. . . . The texts used in Endless Prayers are sacred texts from different traditions and languages of the Near East, like Persian, Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic. Also poetry, especially Rumi. Each individual Endless Prayer piece follows just one text—one, for instance, is a poem by Rumi; another, a Hebrew prayer; and yet another, the Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic, the language of Jesus . . .

EGYet, in your Dome paintings, there isn’t any text or inscription.

YZKNo, there isn’t. Initially there was just white paint, a circular geometry made out of white painted brick shapes that constituted a sort of mandala with a white center—as if light were coming out of there.

In the “Dome” paintings, there is a kind of alchemical process, a kind of reference to alchemy.

Y.Z. Kami

EGThe luminosity of the white in the Domes is truly incredible.

YZKIn a sense, that is what the white Domes refer to—the experience of white light.

EGThere is a feeling of serenity and contemplation when one is in front of your Dome paintings—it is as if they asked you to spend some time in order to perceive them. The colors you use for the Domes—white, black, blue, and now gold making a fourth—each have their own kind of permanence.

YZKIn the Dome paintings, there is a kind of alchemical process, a kind of reference to alchemy. You see, in different alchemical traditions from both the East and West, there is a process of transformation, which starts with black, nigredo. This is a black that alchemists call “black that is blacker than black.” This is where my Black Dome paintings come from. The goal is ultimately to achieve the inner gold; however, to get there, you have to go through the long process of washing and cleansing, which is the whiteness, albedo. From this place is the journey to that inner gold. Gold has always been used in sacred art.

EGHow about the blue?

YZKThe blue in those paintings is the blue of the heavens. I have seen this particular blue in certain elements in sacred architecture.

EGI would like to ask you about the significance of hands in your work. In recent years, you have made several paintings of hands in prayer.

YZKMaybe because it is a physical gesture of faith. You see, hands in prayer is a common gesture used in different religious traditions of the East—in Sanskrit, it’s called anjali. This posture of prayer is also common in Christianity. As you know, there is a small drawing by Dürer in the Albertina that is just two hands in prayer; it’s a marvelous drawing. I have painted hands as individual paintings—just by themselves—since as long as I can remember. I think it was Pascal who said that—and I’m paraphrasing—“the hands carry the soul.”

Artwork © Y.Z. Kami; text © Elena Geuna and Y.Z. Kami; interview originally published in the 2019 monograph Y.Z. Kami, co-published by Gagosian and Skira