Urs Fischer: Wave

In this video, Urs Fischer elaborates on the creative process behind his public installation Wave, at Place Vendôme, Paris.

June 8, 2020

Installed at Beirut’s Aïshti Foundation in fall 2019, Urs Fischer’s solo exhibition The Lyrical and the Prosaic—his first in the Middle East—remained closed to the public for many months, its opening postponed at first due to the eruption of anti-government demonstrations across Lebanon and then due to the covid-19 crisis. It opened at last in late June 2020. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, curator Massimiliano Gioni traces the material and conceptual tensions that reverberate throughout Fischer’s work.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Liz Kim

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Liz Kim

It is the first time that I’m writing about an exhibition I haven’t seen in person. Urs Fischer’s show in Beirut was supposed to open on October 20, 2019, but the inauguration has been indefinitely postponed due to the storm of protests and demonstrations that swept the city starting a few days earlier, shaking the government and leading to the resignation of Lebanon’s prime minister. The day that I was supposed to leave for Beirut, the Aïshti Foundation got in touch and warned me to hold off my departure, because the streets of the capital were blocked and there would be no way to even get out of the airport once I arrived. So I’m writing this from afar—a situation that seems perfectly in keeping with Fischer’s work, rooted as it is in an interrogation of the distance that separates presence and absence, the heavy and the weightless.

This book carefully documents the exhibition and the works on view, but also includes photos that Fischer and his collaborators took during the protests around Beirut, where they remained for nearly a month, first to prepare the exhibition and then stranded due to the demonstrations. This dialogue between the museum and the street, between the inside and the outside, seems to echo throughout Fischer’s art, as he systematically attempts to find new ways to disarticulate and complicate the relationships that tie reality and fiction, or, more broadly, the prosaic and the lyrical, to use the terms chosen by Fischer to title this exhibition.

In some ways, Fischer’s work is traditional. Though he is known for some of the most radical artistic acts of the past few decades—such as digging a huge crater in a gallery floor or sawing giant holes through the walls of museums and exhibition spaces—Fischer continues to employ the academic genres of painting and sculpture, although he engages with them in ways that progressively dissolve their boundaries and definitions.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Stefan Altenburger

Some of his paintings, for instance, are both painted and printed: they begin as collaged digital images, manipulated on the computer and then silkscreened and painted onto massive panels, in a process of gradual dematerialization and simultaneous materialization, where expressionism and detachment seem blended to the point of becoming indistinguishable. Fischer’s paintings seem characterized by a sense of icy distance, yet stirring under their surface is a sudden urgency and telluric power. Or, conversely, a sense of personal expressiveness is arrived at by deploying tools normally utilized for the mechanical reproduction of images, depersonalizing the intimate subjectivity traditionally associated with abstract gestures. As such, Fischer’s painting appears to rest on a series of contradictions: bold gesture and inexpressiveness, improvisation and replication, hand and machine, flesh and data.

These aspects become even more explicit, and even more complex, in a series of recent paintings made on iPads. These works literally sprang up under the artist’s fingertips, in what could be described as the modern-day equivalent of the intimate realm of the sketchbook. But these pictures are simultaneously automatic and automated: in them, the dream life of the unconscious is immediately trapped in the artificial world of postproduction.

As in our everyday lives, in these paintings all intimacy has been co-opted by artifice: the self is immediately reflected in the mirror of the screen, on the inorganic surface of the phone and iPad. The space of personal confession has already become the space of sharing and marketing. The self has already been othered: even the deepest unconscious is instantly detached and shared, commercialized, broadcast.

It is no coincidence that windows are a recurring image in Fischer’s paintings. His iPad pictures often present a succession of views of rooms with windows opening not onto natural backgrounds but onto artificial, vaguely cartoonish panoramas. Sometimes the background instead duplicates itself and rises up to the surface in the form of inlaid images and repeated patterns. Fischer’s works are contemporary mises en abyme, in which the windows frame not the outside world, but rather a series of images dizzyingly superimposed as if on a computer desktop: these are races to stand still, voyages around a room—inlays that are no longer windows, but screens.

In the end, this confusion between interior and exterior is also the guiding principle of Fischer’s spectacular installation made up of thousands of droplets, suspended like a freeze-frame of a rainstorm. Part Sturm und Drang and part Wile E. Coyote, Melody (2019) invades the Aïshti Foundation’s largest gallery with a downpour that is both dramatic and comic, opera and vaudeville.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Stefan Altenburger

Like his paintings, Fischer’s installations combine hyperrealism and caricature, crude reality and cunning manipulation, the physical and the virtual. Standing before them, one has the impression of looking at a photoshopped version of reality—a digital surrealism founded on a Pantagruelian appetite for images that are voraciously consumed. But it is this constant leap between the visual and the visceral that drives all of Fischer’s work. The result is a proliferation of images that preserve the volatility to which digital media have accustomed us, yet seem tethered to a physicality that is somehow baroque, weighed down as it is with flesh and matter.

From this perspective, all of Fischer’s work could be seen as an effort—a Sisyphean one, perhaps—to grant body and weight to the immateriality that seems to characterize the digital world. The process of embodiment staged in Fischer’s work is often violent, which is perhaps why many of his subjects seem to be decomposing, like rotten food. At other times organic materials are presented in full decay, as still lifes that are both sumptuous and putrid, like magnificent seventeenth-century tableaux.

Even in his most vertiginous accumulations of digital images—wallpaper installations such as HEADZ, 49 Market St. (2019), with its thousands of reproduced drawings, being among the most recent and extreme examples—Fischer seems to emphasize the physical nature of his supports, showing off the metal framework of walls and partitions or revealing the concrete pillars that hold up the entire exhibition space.

There is no such thing as an unembodied image in Fischer’s world, no images without flesh in his universe. In its investigation into the physicality of images, Fischer’s work reconnects to a lineage of contemporary sculptors such as Isa Genzken, Martin Kippenberger, Bruce Nauman, Claes Oldenburg, Dieter Roth, and Franz West, all equally fascinated by the unstable beauty of humble materials and by the tension between order and disorder, form and its dissolution, the rational and the physical. Like these predecessors—to whom one might add influences dating back to Surrealism and Dada, especially in their exploration of the links between carnality and vision—Fischer compounds his sculptures and installations into extraordinary concentrations of bodies, objects, and images, in a conflation of the real and the imaginary.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Stefan Altenburger

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Stefan Altenburger

Nowhere is this attitude more apparent than in Fischer’s polychrome bronzes and wax sculptures, many examples of which are on display in the Aïshti Foundation show. These miniaturized sculptures have the feel of garden gnomes and similar forms of folk art, but also forge a dialogue with the masters of Swiss understatement, Fischli & Weiss. Like their works in clay and rubber, Fischer’s pieces are drawing-room epiphanies: pointless little miracles that serve as backdrops for armchair voyages, somewhere between Jacques Tati and Raymond Roussel. As in the novels of Robert Walser, another Swiss man enamored of minuteness, in Fischer’s microworlds everything that is small and humble seems beautiful and appealing, as if glimpsed in a dream.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Stefan Altenburger

A similar fairy-tale sensibility can be found in Fischer’s wax sculptures, which melt into surreal landscapes with precipices and ravines resembling details of frottages by Max Ernst. While Fischer’s polychrome bronzes belong to the world of fantasy, in the vein of those pictures of medieval fairs that capture the enchanted abundance of an imagined Cockaigne, his wax sculptures instead possess the sinister depth of baroque grottos and sylvan metamorphoses, like miniature Boboli Gardens or macabre visions not too dissimilar from the memento mori, anatomical studies, and plague scenes depicted by seventeenth-century wax modeler Gaetano Zumbo. In Fischer’s case, however, these incrustations are overlaid with a delicate veneer of Pop: the colors and even the title of What if the Phone Rings (2003) evoke Hollywood comedies or melodramas from the 1950s—more Douglas Sirk than Billy Wilder, though.

Installation view, Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020. Photo: Urs Fischer

Shimmers of lightness aside, Fischer’s art always preserves a considerable specific weight, an almost prodigious mass. And this tension between the lightness of images and the gravity—in the sense of both weight and solemnity—of sculptures and bodies is the key paradox of Fischer’s art, which is often conceived and molded in the digital realm, but keeps leading us back to the material one.

After all, the protests in Beirut erupted when, after a series of austerity measures, the government announced its intent to even tax voice calls on WhatsApp—that is, when something immaterial was violently dragged into reality. Because, despite all illusions that the world is becoming more and more intangible and ephemeral, it is still bodies that must carry its weight. And, as the insatiable accumulations in Fischer’s art remind us, we are mostly stomachs in the end. Our eyes, too, are mouths, and nowadays we don’t just look at images—we chew on them like crusts of bread.

January 2020

New York

Text excerpted from Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic (Beirut: Aïshti Foundation; New York: Kiito-San, 2020), the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, October 20, 2019–October 31, 2020

Artwork © Urs Fischer

Massimiliano Gioni is the artistic director of the New Museum in New York. He has curated various international exhibitions, including the 55th Venice Biennale (2013) and the 8th Gwangju Biennale (2010), among others. He has collaborated with Urs Fischer on a number of projects, including most recently Urs Fischer: The Lyrical and the Prosaic (Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, 2019–20), which he curated.

In this video, Urs Fischer elaborates on the creative process behind his public installation Wave, at Place Vendôme, Paris.

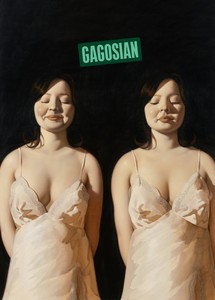

The Winter 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Anna Weyant’s Two Eileens (2022) on its cover.

Urs Fischer sits down with his friend the author and artist Eric Sanders to address the perfect viewer, the effects of marketing, and the limits of human understanding.

The exhibition Urs Fischer: Lovers at Museo Jumex, Mexico City, brings together works from international public and private collections as well as from the artist’s own archive, alongside new pieces made especially for the exhibition. To mark this momentous twenty-year survey, the artist sits down with the exhibition’s curator, Francesco Bonami, to discuss the installation.

On the eve of Awol Erizku’s exhibition in New York, he and Urs Fischer discuss what it means to be an image maker, the beauty of blurring genres, the fetishization of authorship, and their shared love for Los Angeles.

William Middleton traces the development of the new institution, examining the collaboration between the collector François Pinault and the architect Tadao Ando in revitalizing the historic space. Middleton also speaks with artists Tatiana Trouvé and Albert Oehlen about Pinault’s passion as a collector, and with the Bouroullec brothers, who created design features for the interiors and exteriors of the museum.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

Catalyzed by the exhibition Crushed, Cast, Constructed: Sculpture by John Chamberlain, Urs Fischer, and Charles Ray, Alice Godwin examines the legacy and development of a Surrealist ethos in selected works from three contemporary sculptors.

Fruit and vegetables are a recurring motif in Urs Fischer’s visual vocabulary, introducing the dimension of time while elaborating on the art historical tradition of the vanitas. Here, curator Francesco Bonami traces this thread through the artist’s sculptures and paintings of the past two decades.

Urs Fischer talks about reading during the pandemic lockdown, sharing five books—both fiction and nonfiction—that he has turned to while in self-isolation.

Journalist and curator Judith Benhamou-Huet leads a tour of the exhibition Urs Fischer: Leo at Gagosian, Paris.

Urs Fischer and choreographer Madeline Hollander speak with novelist Natasha Stagg about the ways in which choreographic experimentation and an interest in our ability to project emotion onto objects led to the one-of-a-kind project PLAY.