Awol Erizku is a multidisciplinary artist working in photography, film, sculpture, and installation, creating a new vernacular that bridges the gap between African and African American visual culture, referencing art history, hip hop, and spirituality, among other subjects, in his work.

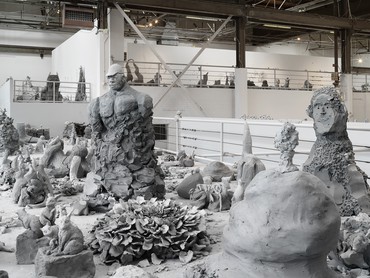

Urs Fischer mines the potential of materials from clay, steel, and paint to bread, dirt, and produce to create works that disorient and bewilder. Through scale distortions, illusion, and the juxtaposition of common objects, his sculptures, paintings, photographs, and large-scale installations explore themes of perception and representation while maintaining a witty irreverence. Photo: RobertBanat.com

Awol Erizku I remember the first time I encountered your work in person, when an exhibition at the former Marciano Art Foundation in LA included a grouping of your Problem Paintings. It blew me away. Those works resonated with me as an image maker so directly; it was clear to me that you don’t have boundaries, and that’s something I work toward, too. I did my undergrad at Cooper Union in New York, and I never declared a major. When I went to Yale, I was in the photography department simply because I had more image-based work at that point, but once I got in, I was making sculpture, and the professors didn’t like that at all. Long story long, when I see artists who can just flow through multiple disciplines without any boundaries, without any sort of rigidity, it affects me. And correct me if I’m wrong, but my read of your work is that it’s exceedingly fluid.

Urs Fischer I like that you said “image maker”; that’s how I understand my practice, too. It’s funny, I started in photography as well, for the same reason. When you come from photography, even when you do things by hand later, you think differently. When I was nineteen, I moved to Amsterdam and I ended up in a postgraduate program there, and that was the first time I encountered people who had a real “arts education.” There were all these kids coming out of art school and their heads were already filled with the “right order,” the “right thing,” “This is how you do it.” They were so structured, I was in shock. I realized that the guys who were painters had their heroes who they wanted to take down . . . It was very macho, some idea of, This is your hero/dad/enemy, you adore it but you’ve got to kill it.

AE Yes. I know the type.

UF They weren’t looking at anything else, they were just set on that battle. It didn’t make sense to me, then or now, and it’s part of why I’m really hopeful and pleased with the present moment. That battle, that historical reverence, isn’t as constricting today. Through cultural shifts, through social media, it seems that everything can originate from everywhere and mix. This is so different from how I grew up. Looking at your work and seeing the progression over time, it’s great. If you come from a place and time where it’s more open already, you can enjoy all these things. It’s like going to a buffet and just eating instead of having to sit at the table and wait.

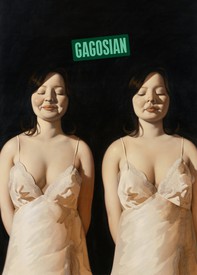

AE Exactly. I have to say, this is one of the more compelling things about your practice, that it comes as a buffet. When I look at your work, I’m not thinking about Urs the painter or Urs the sculptor. I don’t process it the way I would a Gerhard Richter, for example. I think you’ve taken that father figure and made an unprecedented, surprise move. I often approach the process of making art much like the game of chess: if we’re playing against our father/mother figures, it’s then up to us to make the next move, since they’ve already made the first. The primary motivation is to keep the game moving forward. Especially now, with social media and technology advancing every year, you have to update it, right? You have to use what’s available to you to update everything around you. Part of what I’m doing in this exhibition with Gagosian is just that: I’m collapsing the concept of the sphinx, which in Egyptian mythology and culture has one, semistatic interpretation: it’s solely depicted with a human head and the body of a lion. But over time, multiple cultures have contributed interpretations of this creature. In ancient Greece it has the wings of a falcon, with feminine attributes; in Asia it has a snake for a tail. So I try to play with all these things and deconstruct these myths in time and space through image and sculptural form. The works will be presented as a constellation, with a rotating Nefertiti disco ball in the center of the gallery. I remember thinking, Urs would get a kick out of this work!

Music . . . scent . . . artmaking . . . to me there are no borders. If I’m listening to a song and I’m thinking about some historical figure, some historical moment, some monolith, I’m immediately drawn to blend these concepts to synthesize something new. This ties into the sphinx as well.

UF I look forward to seeing the sphinx. I’m Egypt obsessed. To this day, one of my favorite artworks ever made is the pyramid. It’s the simplest form of connection to a cosmic thing. I mean, what can I do in the face of that?

I often approach the process of making art much like the game of chess. . . . The primary motivation is to keep the game moving forward.

Awol Erizku

AE Here we are, from two completely different backgrounds, yet we’re talking about the sphinx and the pyramids. I love that you reference the pyramids as one of your biggest artistic inspirations, instead of feeling you have to stick to European inspirations. What I aim to contribute to the ongoing global conversation about Blackness is to point to areas that we all have access to by way of an affinity to cultural heritage. It’s about how we interpret it and how we bring our own twist to it, how we update it, which, again, I feel you do so freely, and it’s admirable. What’s the secret?

UF I don’t know! It’s just the way I think. Everything we do is one thing. Everybody that adds anything at any point in time is in existence, and everything only lives if it’s seen, experienced, and passed on. Otherwise it becomes dormant or it dies.

The other thing is, we only see what we see. I’m always shocked how rarely I see something new, and that’s not because it’s not there; it’s incredible how easily your brain erases information and singles out parts that your neural functioning can connect. With art, with images, you can tap in and you can be part of anything, which is a creative act. You can communicate with any point in history and place. I don’t understand myself as somebody with a message—

AE Oh, that’s interesting.

UF —and then I think, Maybe you’re right, I don’t know. My message is that I just try to have fun with this, and if that’s not message enough for you, then that’s okay.

AE Right. These days it’s a common preconceived notion about art that it’s supposed to have a direct message. I think some of the weight I’ve had as an artist, and maybe it’s self-prescribed, is that I feel my work should have a message or that it should reflect the time. And in many cases I push against that. I never thought I needed to stick to any sort of plan. I think the artist who has this one body of work that keeps evolving, and just changes incrementally until it becomes a megahit with museums and whatnot—that isn’t the model I find exciting. I almost think of my practice as a Maison Margiela runway show. I could never stage this sphinx show again. I don’t think I’ve ever put any show that I’ve done in any city back together in another city.

Can we discuss the idea of authorship in art, and in your work in particular? I definitely want to talk about your Yes project [2011–].

UF I mean, what is an author, anyway? The problem of being an author is there’s a fetish around it, and I’m personally buying that fetish too with other artists. So to try to question that impulse to fetishize, for a while I tried to make these works out of wallpaper, and from there I moved to these bigger clay sculptures that started from the same premise. You make these sculptures that lie before the moment you make an image, so it’s just really like an action. Who’s in control of the boundaries?

AE I feel like some people should stay within a boundary, you know what I mean? I’m a little biased, but I sometimes see painters who pick up a camera and think they can make a decent photograph, and it’s like, Yeah, that’s not it.

UF Why not?

AE In any practice, I think, it’s beneficial to have some knowledge of the history of the medium, so that you have some form of anchor, some sort of grounding. I’m a purist at times; I believe that if you don’t have an understanding of where you belong in history, you’re just spinning

in circles.

UF But who are we to say? I mean, the way I see any artwork is, it just gives. It’s there for you, and you can hate it, you can love it, you can be inspired by it, you can ignore it. It’s just there. It’s just a thing.

AE Fair. That’s a generous rebuttal.

UF I’m very often exactly where you are, I think, This is horrible, this is garbage, but in a way, every time I say this, it’s to shut myself up. What do you think about authorship?

AE I’m a huge fan of the Pictures-generation artists, like Richard Prince, John Baldessari, and Sarah Charlesworth; I actually had the pleasure of studying with Prince when he was at Yale as a visiting artist. My respect for him and others, again, goes back to chess: as long as you’re making the next move, you can take whatever is out there to have. If you take an image from someone and you’ve done something to change it and then you’re sort of rocking with that, that’s fine. It’s like bootleggers, right?

UF Or language. Which word did I invent? I use it every day, but is it mine?

AE Exactly.

UF But the way I use it is my own way. It’s not even that much my own, but it’s for my own use in some way to express something.

AE Could we go back to Yes? I’d love to hear more about that project.

UF It was the best experience I ever had making art, because it didn’t matter what anybody made. There were only two rules. First, we used clay. We just used one material, making it akin to a minimalist artwork. And the other thing was, there was no editing. I didn’t edit what others made, and no one else was allowed to edit their fellow participants. There were always aggressive people who wanted to destroy, but if it got to be a little much, you had a chat with them, got their mind on something else, led them back to a place of no editing. You said yes to the whole thing.

What effect does Los Angeles have on your artmaking? When I look at your work—me, I’m a cyclist in LA— I see a lot of the city in there.

AE My mom was just in town to celebrate my daughter’s birthday this past week, and she was like, “You have to move back to New York.” I’ve been in LA seven years now, and I’m like, “You know, Mom, I can work until three in the morning, and if I just get in my car and drive a mile, I’m already home. In New York, I can’t imagine having a studio in Red Hook and then having to drive.” I don’t miss that about New York. I think LA gave me freedom in a sense.

Also, LA has had an effect on my palette. In New York, my studio was in the basement of a flower shop on Lafayette Street, and it was just pitch black, no windows, all I heard were the trains, so in LA it was nice to be out in the world and drag anything in from the street. I used to collect stop signs and put hoops on them, and some of the early tarp paintings were heavily inspired by the community. My first studio was off Stanford and Pico, right by the Coca-Cola factory in Downtown, and there was so much happening. So the work got bigger, the palette expanded, and I got to work with flowers a lot more.

UF I love the car with the flowers coming out of it; it’s awesome. Also, the erasing of the markings, the composition, in your painting—there’s a sense of receding and the passage of time.

AE When you live in LA, if you’re a cyclist or you drive around all the time, you’re bound to see these types of markings and erasures while in motion. It’s been very inspiring.

UF There’s a large factory that I see on my way to the studio in LA, it has a blue wall, and there are always new markings on it: text, graffiti, all this kind of stuff. And with great frequency they attempt to fix it with different kinds of blue; it never matches, and the blue becomes so beautiful like that. I just see so much creativity in LA’s unfinishedness in some way. It’s made me start to love garbage. I remember the first time I came to the United States, when I was ten, and we drove to South Carolina from the airport in Atlanta. On the freeways back then there was no fine for littering and they were just giant avenues of garbage, people just threw stuff out of their cars. I never saw something like that before, and it hurt me when I saw that as a kid. But when I see garbage now, I think it’s beautiful. I can’t speak for nature, but it’s just a reminder of who we are, and it’s right there in front of us, and the absurdity of it . . . I see LA as a very flat, sprawling monument of our idiocy.

AE Well, you should come by my studio. It’s right by one of those big dumpsters, and I can smell it from time to time when they’re burning stuff, and I’m like, This can’t be healthy.

UF Next time I’m out, let’s go on a bike ride.

AE Let’s do it. I’m down.

UF Because you know, on the bike, I go on little side streets, I go in-between buildings, when there’s a hole in a fence I ride through. And in some ways, in LA you seem to see so many layers from the side, versus in New York, where it’s maybe hidden in the verticalness of it all. But you see all these things in the parallel societies of the two cities. I see that when I look at some of your paintings, I feel that.

AE I appreciate that. I still have more work to do, but I’ll take it.

I recently started following you on Instagram, and you have some NFT projects coming up. I want to know where you think that’s going to go. There are people who are literally selling anything and just calling it an NFT, and to me, when it first started, I was like, Yeah, NFTs, I get it, I can sell this digital thing. I think the way you’re doing it is actually the smart way, because it feels like it was intended to be an NFT, as opposed to . . . I think I just saw somebody minted [former Tampa Bay Buccaneers wide receiver] Antonio Brown’s reaction to his teammates [in leaving a football game in the middle], and they’re now selling that as an NFT. First of all, who’s buying it? And what does it really mean? Anybody can access that clip on their laptop, you know what I mean?

UF Who knows where it’s going—what I realize is, nobody knows. There are things people react to. People started to pay attention to the sixty-whatever-million-dollar NFT sale—all of a sudden, Oh my God, what is this? Or, This is not art. When you look at the short history it has, from my understanding and talking to a lot of people who have been involved in it from the start, it actually began as more of a philosophical question: Can you attach an image to a piece of blockchain? What could that be, and how could it communicate? Then the way I understand all of that is that in some way it’s a collective subconscious, with all its ugly sides and beautiful sides. And the number of people who engage in it is so much larger than the number who engage in art.

The problem in art is that you’re forced to tell one story. That’s why it feels so sensitive at times. Every story you tell adds up to one story in the end, and logically we all slip.

Urs Fischer

AE I thought I understood it when it was first becoming a thing, and now I’m completely lost again.

UF Yeah, but that’s kind of great, no?

AE Yeah, it is, it lets you keep wandering and hopefully stumble on something.

UF It’s amazing, all of a sudden you have hordes of “experts” who everybody talks about. It’s like they come out of nowhere, like mushrooms. It just grows out of . . . Poof! You know? Would you ever do an NFT?

AE I’ve been approached by a few people, but I’ve always decided to abstain. Then when I came across your NFTs, I thought, Oh, this is great because I can see the development from one thing to another. Whereas I think a lot of people think of NFTs as like, Let’s mint your most popular piece and then that’s an NFT.

UF Yeah, that’s a money-grab, you know. But I mean, why not?

AE But that’s not interesting. I like to think of NFTs as a space where I can do something new and completely justified in that form.

UF The problem in art, I think, personally, is that you’re forced to tell one story. That’s why it feels so sensitive at times. It’s as if you have clear water and if you drop a drop of yellow food coloring in the glass, everything gets tainted. So if your story has authenticity but you do something sloppy later, it makes what you said before unbelievable. Every story you tell adds up to one story in the end, and logically we all slip. We all find ourselves not in the best frame of mind sometimes, and there’s just so little room for that.

This goes back to the fetishization of the artist. It all gets linked to some kind of narrative, and I’m a sucker for this too: if I see somebody fuck up, I’m like, Maybe they weren’t that good from the start. But why do I have to put these two things together? Let the person have a life. And I think that’s the problem with collaborations if they don’t feel like an extension of your work—if they exploit your work in some way, they undermine everything else you do.

AE Troubling [laughs].

UF I mean, it’s incomprehensibly complicated and painful, but also very—I don’t know, human, to think in narratives.

AE I’m thinking about that David Hammons exhibition in 2019 at Hauser & Wirth in LA. In terms of narrative—and what we were speaking about earlier, about Los Angeles and the complexity of its beauty mixed with certain painful scenes and existences—the show was very conflicting. The opening night alone, where the art world came downtown to see Hammons’s tents in the gallery space, knowing that these things being presented as art were made in imitation of the homeless encampments that you had to drive through to get there . . . it’s tricky.

UF Could you elaborate on what you mean by “conflicting”?

AE When you know Hammons’s practice, you know that it’s meant to do more, but if it wasn’t Hammons, if another artist did a piece like that, would we talk about it in the same way?

UF Context is the new content.

AE Yeah. Unfortunately. And as artists, as these community relationships grow and build, what’s our responsibility to bring on that sort of change, or to advocate for it? I’m still trying to decide about that show.

UF I hear what you’re saying. But on the other hand, it stirs a lot of conversation. It moves discourse and it conflicts people. The way I understand a lot of art, in any medium, any form, is in terms of energy. If you sing, you make molecules vibrate through your body, and somehow they travel and you assemble this stuff. Ideas travel, provocations travel, concepts travel. The existence of the work defines the pitfalls and limitations. When you’re blindfolded and you walk into a room and bump into something, it doesn’t matter if the idea is good or bad—it’s just something that’s there and it’s real.

Awol Erizku: Memories of a Lost Sphinx, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, March 10–April 16, 2022