Urs Fischer: Wave

In this video, Urs Fischer elaborates on the creative process behind his public installation Wave, at Place Vendôme, Paris.

Winter 2022 Issue

Urs Fischer sits down with his friend the author and artist Eric Sanders to address the perfect viewer, the effects of marketing, and the limits of human understanding.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #501, 2022, raw data files, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering and URL. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #501, 2022, raw data files, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering and URL. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

Eric SandersDid you always enjoy the work, or is that a newer experience?

Urs FischerYeah, I always enjoyed the work, but the understanding of how to belong—that’s where most of my not liking it comes from. More so came from. You want to communicate, but the communication can feel very limited because we define what is possible, you know? It’s like a village, and this village has its own rules, its own mythologies. Or, you’re defined from the outside. And that’s more where my discomfort, the not fun part, comes from.

ESI get that, because you can’t control the framework or the context within which you find yourself. According to the world, you’re an “artist,” you’re a “sculptor,” this is an “art gallery.” There are all these predefined rules. How can you break through? How do you overwhelm someone and make them forget all of the stuff that isn’t what you’re trying to communicate?

UFDo you think anybody ever felt like they broke through?

ES[laughter] I mean, is it possible?

UFWell, is it possible to enjoy your own work? I mean, besides the process of doing it. Because you never have an experience where you encounter it from the outside.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #118 Rhizome, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

ESSo how much stock, if any, do you put in what other people think of it? Do you care if it actually resonates with them in any way?

UFIn many ways, my dream is always the same: that my work communicates enough by itself, without too much context, that people who don’t engage with art get something out of it. That’s a really gratifying experience, to have someone just see something and think, Wow, that’s cool, and they’re not from within the art world.

ESIs that because you identify more with that person?

UFProbably, yeah [laughter].

ESThat makes total sense. It’s like, who you want to love your work is you [laughs].

UFExactly.

ESDo you know any people who you think see similarly to you?

UFYeah, totally.

ESDo you try to work with them or do you prefer not to, to let them be more objective?

UFThey’re not so much from my trade. I mean, I don’t really have a clear practice, so in some way, I think I identify most with my friends who have a very radical or full-on approach to how they engage in what they do. That’s really something I can relate to. So more than a content thing, it’s about this sense of dedication and fearlessness. That’s very appealing.

ESCan we talk about this cube of random commercial footage that you’ll be presenting in New York this fall? [laughter] It kind of feels like this might be what it’s like to die.

Urs Fischer, Denominator, 2020–22, database, algorithms, and LED cube, 141 ¾ × 141 ¾ × 141 ¾ inches (360 × 360 × 360 cm). Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

UFWell, with this cube, we take footage from 100,000 sources and we algorithmically determine the content of each shot within each commercial, dating from 1950 up to now. So in the last ten, fifteen years, that starts to ramp up, from YouTube to social media to TikTok, you name it. The crazy thing is, if you think about it: before you had imagery generated through technological means, like photography or video, every image was made by hand. And with images made by hand, you have to select what you depict. Back then, we didn’t really have that “industrial consumer products” kind of mentality, you know? If you go to a baroque church, there’s heaven and hell and that’s it. But then, over time, you start to have a new type of imagery that’s made solely to sell stuff, and it has no collective long-term understanding or context. And this new type of commercial imagery has replaced those old images. So when you think of a beach, is that an actual beach you’ve been to, or a beach you saw on a TV show, or some combination of the two? You fill it in. So this collective human experiment—public relations, marketing, advertising, whatever—leads to a complete replacement of any images we have inside us.

ESThat’s what it’s like to do ayahuasca [laughter]: the mind vomits up these images and most of them aren’t yours. Like, almost all of my images are not my images. It’s horrifying.

UFDo you think there was ever a time when everybody had their own images?

ESNo, but if we go back to your idea of what the mind was like before: obviously there was something there, right? It wasn’t just empty space, but it wasn’t this.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #273 Thespian, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #256 Psychogenesis, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

UFNo, it wasn’t this [laughs]. I mean, I’m just fascinated by it. Because all our references, our moods—we need a model for them. So that’s why, when we talk about something, we use a TV show or character to describe the moment. We’re not even aware we’re doing it.

ESDavid Foster Wallace, who’s probably my favorite writer, wrote this great essay in the early 1990s about how television had affected literature [“E Unibus Pluram,” 1993]. He wrote about how writers and artists, gradually over hundreds of years, morphed from writing or depicting things they’d experienced directly, or, let’s say, archetypal myths in their culture or whatever—you know, universal symbols—to, in the twentieth century, starting to refer to mass media, television, as if it were their own memories. And they didn’t know the difference, right? So when you picture an American family, you picture a family in a TV show, not your real family. He’s talking about how our original images have kind of morphed with the bullshit.

UFYeah. If you think of pizza, you don’t think of the pizza you made at home, you think of some gooey shit from a Domino’s advertisement.

ESExactly. It’s very disturbing.

UFI don’t know.

ES[laughs] Tell me what you think.

UFI don’t know what to think. I mean, I will never have a life that’s not like that. I grew up already like that and my desires are already there, and it’s impossible for me to envision a life outside of that. So I’m looking at it—I try to look at it—with this work, for example, in the same way you look at a landscape. If you’ve never seen one or even a picture of one, you would have to look for yourself. There’s no preexisting context delivered to you; it would be you, live in a forest, looking at the thing. So you would see what you see in that landscape. That’s the way I try to look at this collective imagery. It’s just something you look at. You actually look at this, so it’s an active moment.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #227 Interaction, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

ESTotally. And there’s no judgment there.

UFZero, because it’s pointless.

ESIt’s a very wise point. We talked a month or two ago about the glitch of the mind, which is, “How can mind perceive mind?” Right? But you’re trying. You’re trying to project mind outside—and I guess maybe that’s what artists do, is project mind outside. You’re seeing it outside because that’s as close as you can get to seeing inside, you know?

UFYou try to show what you see in some way. And then, through that, you create an image. An image that allows you to see, you know?

ESAt this point in your life and career, do you ever get scared of what’s coming out?

UFNo, I’m more scared of myself than of what’s coming out.

ESBut that’s you, what’s coming out, isn’t it? [laughs]

UFI don’t know. I was thinking about all these cultures and religions that had no images—what do you call it: antiiconography. So they don’t create an image. And in some way, not putting anything out there prevents you from having a false image. But even that led to its own kind of imagery, because there’s always a desire for images.

ESWell . . . we see.

UFExactly, we see. So in some way, I thought, if you’re afraid of an image—or of yourself, of an identity or whatever, or of being sucked into some defining thing—this is an approach to not making a picture but smashing a picture, you know? Instead of abstaining from it, you just overload it. So no image has a chance to become prominent, because there’s such a flood. In a way, it’s the same as the absence of an image, to create this image that’s the overload of an image.

ESThat makes sense. It also gets it out of your system: if you didn’t do this, you would never get this out so that you could move on to the next image, you know?

UFIt’s a catharsis.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #236 Power, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #181 State, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

ESExactly. Getting it out, you know. Puking it up [laughs]. Do you ever think your mind or whatever will stop wanting to vomit up these images?

UFNo.

ESIs that just what it does?

UFThat’s what it does. I love it.

ESYeah. It’s not a bad thing.

UFI have fun doing that.

ESSo you don’t want it to ever be done? There’s no end?

UFNo, I’m enjoying this. This is awesome.

ES[laughs] That’s a great place to be. So what’s the difference between the overload you’re talking about—advertising, consumer products—and going to Yellowstone or something like that and being overwhelmed by nature?

UFBetween drowning in our own garbage, basically?

ESWell, I know it’s just semantics, but why is something that humans created different?

UFOh, it’s not good or bad. I don’t have an opinion but I have an experience. And my experience is, I like what resonates for a long time. That fills me with something and it doesn’t drain me. The other thing can at times drain me. Entertainment can drain me, anything that keeps me busy, busy, busy. There’s just not enough residue. But being overwhelmed by nature—what overwhelms you, the smell, the beauty, the life—

ESThe awe.

UFThe awe, yeah.

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #217 Zodiac, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

Urs Fischer, CHAOS #101 Design, 2022 (still), raw data file, instructions for rendering the artwork in motion, digital rendering, and URL

ESDo you ever experience that in Los Angeles?

UFWell, in Los Angeles there’s a lot of nature. Even the plants that come out of every crack in every sidewalk. There’s a lot of life here.

ESIt’s trying.

UFRemember in the beginning of the pandemic, all the bunnies came out because the roads were empty?

ESYeah, you used to see wolves in the parks.

UFSuddenly there was all this wildlife that was hopping around on the streets.

ESYeah, it was insane. . . . There was this book years ago called The World without Us [2007]. This guy [Alan Weisman] just ran through, as literally as possible, what would happen if the human species were gone. And you know, within a month, this is what it would look like and feel like to walk around New York City: a bald eagle flies through, and there’s a bobcat. Like it was right there the whole time, pressing at the gates, and we kept it out. A bear wanders through fucking Manhattan, you know? [laughter] Does that bring you peace, to think that?

UFThat does.

ES[laughs] Do you hate the human species?

UFYou know, we all try to make sense of why we’re here, and it’s very confusing having to be a human being. We’re not exactly smart the way we go about things, even though we think we’re very intelligent. It’s a superconfused experience.

ES[laughs] The most confused animal of all time.

UFYeah.

ESOr the dumbest animal of all time [laughs].

UFYeah.

Artwork © Urs Fischer

Urs Fischer: Denominator, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, September 9–October 15, 2022

Urs Fischer: CHAOS #1–#500, Gagosian at the Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, August 20–October 29, 2022

Eric Sanders is a Los Angeles–based writer and artist.

In this video, Urs Fischer elaborates on the creative process behind his public installation Wave, at Place Vendôme, Paris.

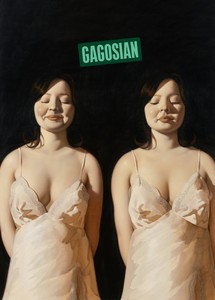

The Winter 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Anna Weyant’s Two Eileens (2022) on its cover.

The exhibition Urs Fischer: Lovers at Museo Jumex, Mexico City, brings together works from international public and private collections as well as from the artist’s own archive, alongside new pieces made especially for the exhibition. To mark this momentous twenty-year survey, the artist sits down with the exhibition’s curator, Francesco Bonami, to discuss the installation.

On the eve of Awol Erizku’s exhibition in New York, he and Urs Fischer discuss what it means to be an image maker, the beauty of blurring genres, the fetishization of authorship, and their shared love for Los Angeles.

William Middleton traces the development of the new institution, examining the collaboration between the collector François Pinault and the architect Tadao Ando in revitalizing the historic space. Middleton also speaks with artists Tatiana Trouvé and Albert Oehlen about Pinault’s passion as a collector, and with the Bouroullec brothers, who created design features for the interiors and exteriors of the museum.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

Catalyzed by the exhibition Crushed, Cast, Constructed: Sculpture by John Chamberlain, Urs Fischer, and Charles Ray, Alice Godwin examines the legacy and development of a Surrealist ethos in selected works from three contemporary sculptors.

In his introduction to the catalogue for Urs Fischer’s exhibition The Lyrical and the Prosaic, at the Aïshti Foundation in Beirut, curator Massimiliano Gioni traces the material and conceptual tensions that reverberate throughout the artist’s paintings, sculptures, installations, and interventions.

Fruit and vegetables are a recurring motif in Urs Fischer’s visual vocabulary, introducing the dimension of time while elaborating on the art historical tradition of the vanitas. Here, curator Francesco Bonami traces this thread through the artist’s sculptures and paintings of the past two decades.

Urs Fischer talks about reading during the pandemic lockdown, sharing five books—both fiction and nonfiction—that he has turned to while in self-isolation.

Journalist and curator Judith Benhamou-Huet leads a tour of the exhibition Urs Fischer: Leo at Gagosian, Paris.

Urs Fischer and choreographer Madeline Hollander speak with novelist Natasha Stagg about the ways in which choreographic experimentation and an interest in our ability to project emotion onto objects led to the one-of-a-kind project PLAY.