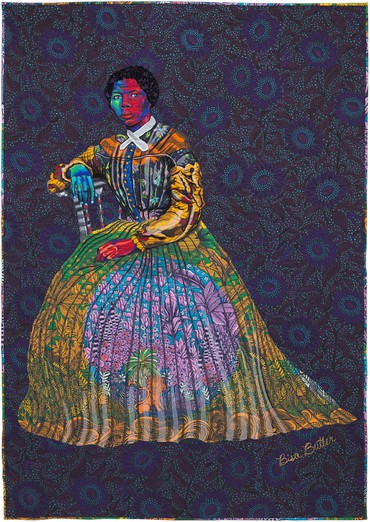

Bisa Butler is a portrait quilter based in Orange, New Jersey. Her work celebrates African American culture through portraits of individuals from ordinary walks of life. Butler received her degree from Howard University, and her work has been shown in exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, among other institutions.

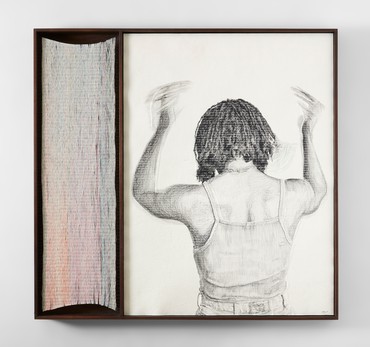

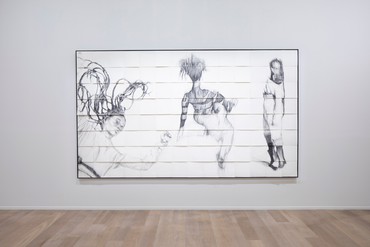

Kenturah Davis is an artist working in Los Angeles, California and Accra, Ghana. In drawings, textiles, sculpture, and performances, she uses text as a point of departure to explore the fundamental role that language has in shaping how we understand ourselves and the world around us. Davis earned a BA from Occidental College and an MFA from the Yale University School of Art, and was an inaugural artist fellow at NXTHVN. Her work has been included in institutional exhibitions in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe.

Lara Mashayekh is an art writer with an interest in global modern and contemporary art. She holds a degree in art history from the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

Lara MashayekhIf you could each invite someone for dinner, who would it be?

Bisa ButlerOh, my gosh [laughter]. I recently saw a snapshot of Romare Bearden in a gallery press release. I have heard older folks refer to him as “Romi” and am told that he would come with a chicken—have you ever heard that, Kenturah?

Kenturah DavisNo [laughter]. A cooked chicken?

BBYes, a whole cooked chicken. He’d bring one whenever he was invited over. I thought about how old-school that was and how he was originally from North Carolina, raised by his grandparents. I would love to have been able to talk to him. But then I started thinking, What if I asked Romare Bearden for a critique of my work? [laughter] What would he have said? Romare would’ve been wonderful to meet.

KDI’ve been reading a lot about the invention of writing, so whoever made that leap from a counting system to transcribing ideas would be the person I’d choose. If I had to pick, I’d probably talk to an Egyptian scribe.

LMTell us about your interest in linguistics. You both make textiles and portraits, and it intrigues me that you encountered those genres, Kenturah, by studying Egyptian etymology.

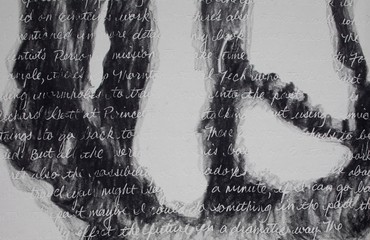

KDYes. When I was in grad school [at Yale], I was interested in language and thinking about writing as a type of drawing. I took a class on the invention of writing that focused on Mesopotamia and Egypt and I wrote a paper about a hieroglyph for “textile.” Writing that paper made me realize that weaving was invented long before writing as a material in which to encode information. Considering how we assign meaning to forms, in relation to the invention of those technologies, is what got me fixated on the intersections of writing and weaving.

LMHow did you become so invested in using Japanese weaving techniques? Tell us about your use of colors and shadows.

KDI’ve been working with Japanese papers for a while. That led me to discover the shifu process, whereby handmade paper can be processed into a thread that I can weave with. I gave myself permission to introduce color after making textiles, and was even inspired by West African fabrics. Weaving enabled me to thread that component into my drawings, so I started introducing color in a purposeful way. Bisa, color has always been an important part of your work, right?

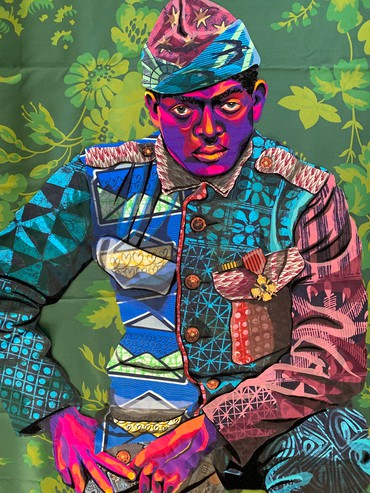

BBOh, I love it intensely, and I think that’s why the colors are as bright as they are. I have West African roots, so the textiles I was surrounded by were always extremely bright. If you look at West African women—they just casually go to the marketplace and I think, But you’re wearing that? [laughter] In Ghana, it’s a totally different aesthetic, and their fabrics mean something. I am really focused on learning the humorous stories behind each material. There’s one fabric that African women refer to as “men are not loyal” [laughs]. Another one, called genido, implies that a woman is dating a younger, handsome man. I love fabric’s intrinsic ability to convey more in my works.

our reverence for fashion and theater is something that can be traced all the way back in our ancestry, crossing cultures, generations, and even finances.

Bisa Butler

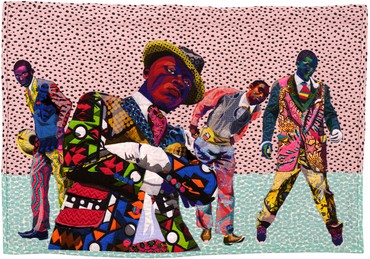

LM While we’re on the topic of fashion and textiles, what was the inspiration behind your work Les Sapeurs [2018], Bisa? Les Sapeurs refers to a fashion movement in the DRC, if I remember correctly.

BBWell, I found a photograph by Daniele Tamagni of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes. The term sapeur comes from the French slang “se saper,” which means to dress with class; the society’s acronym derives from that. I immediately appreciated how we are always able to transform our circumstances. When I was growing up, in the 1980s, at the beginning of Dapper Dan, it was perceived as taboo and wasteful if Black people in urban settings wore big gold jewelry and bright patterns. Yet our reverence for fashion and theater is something that can be traced all the way back in our ancestry, crossing cultures, generations, and even finances. I realized, when I saw the photograph, that there was a connection to the 1980s: to the Kangol hats and Cazal glasses and wearing Gucci from head to toe. The sapeurs looked so proud, beautiful, and strong.

The image of these men speaks to us as Americans, since anyone can see what it is visually, but to African people, I want to say something special about those men; if they see genido or grotto fabrics, they understand that I’m specifically speaking to them.

KDI strive to make objects that reveal themselves at different levels and times, based on who is engaging with them. There is a layer of recognition for some and a layer of mystery for others. It’s an embodiment of our natural engagement as people, in terms of what we learn and perceive from one another. There are always things we will never quite have access to.

BBYes. Going back to the subject of language again, it reminds me of code switching. We are speaking to various people at different levels of understanding. I value how the work can be as layered as we are as people. We’re all multilayered individuals, with things we want to reveal and things we don’t; and then there are other things that maybe we’re not even aware we’re revealing.

LMIndeed. Do you ever feel a moral impetus to address social issues when you’re making your work, or is it a subconscious act?

BBI was trained to respond to the needs of Black people. My professors at Howard were from the era of the 1960s; they were all AfriCOBRA artists and Black activists who had demanded change back when the university pushed to assimilate with greater white society. By the time I got there in the 1990s, they were fully entrenched in celebrating Black culture. But on our way to campus, there were constant reminders of Black folks who were suffering from mental health and addiction issues and were struggling financially, economically, and educationally. We couldn’t merely make “art for art’s sake.” I was part of a community. I remember we were all required to take a course called “Blacks in the Arts,” regardless of our major. It was eye-opening to become versed in the art of the Harlem Renaissance and philosophies of the Negritude movement. I still operate with that mindset of my responsibility as an artist.

KDI always refer to Toni Morrison as my guide for describing my motivations and considering who I’m addressing. My work centers a community of friends or mutual friends, so that sense of belonging is a given.

When you think about [toni] Morrison, Saidiya Hartman, and the role of writers and artists—we’re all innovating from truth and fiction and blurring it together with our imaginations.

Kenturah Davis

BBAbsolutely. It’s interesting that you mentioned working with people who are connected to you. Did you always do that?

KDI think so. A long time ago, I made that decision because I wanted to have full authorship over the photographs that I use, although I’ll occasionally use archival images for commissions. That narrowed the parameters through which I make drawings, and aids my creativity. I don’t know if you find that, working within the textile world—

BBI do.

KDThere’s a duality; it feels exacting and expansive at the same time. I feel that way about your work too [laughs].

BB[Laughs] I love that—it’s really deep to work with limited supplies or ideas and to test the limits of those concepts and elements.

LMAbsolutely. It’s also fascinating to compare Kenturah’s photo selection process to yours, since you don’t necessarily know the individuals in your portraits personally.

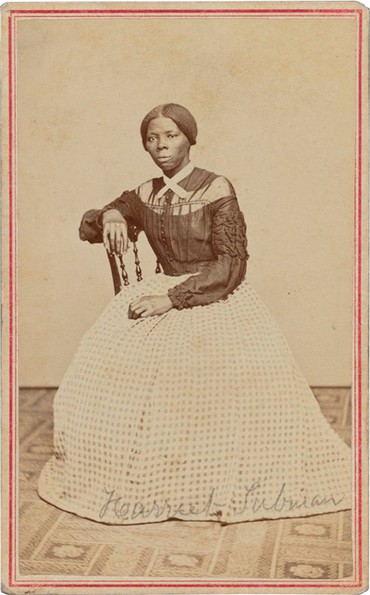

BBYes, I think that’s why I asked you that, Kenturah, about family and friends. I started creating images of family and friends initially, but I’m not a photographer, so I didn’t take their pictures. My early works were all gifts to loved ones, but eventually I had to reevaluate what I wanted my work to say in a public space. I found myself drawn to databases and photos I found online that were reminiscent of family photos like those from my grandmother’s album. I strongly resonated with the photograph of Harriet Tubman that resurfaced a few years ago. I always wondered what she was like and how she looked in her youth. I felt compelled to at least try to do the image justice. You notice so many details when you really observe and scrutinize a person’s photograph. I was looking at her hands and expected them to be rougher. I’ve uncovered so much by looking at that: the waves in her hair were so carefully combed and braided, and her tight-boned dress had all these tucks and pins and boning in it. We don’t really think or talk about Harriet Tubman in that way, that maybe she liked this elaborate dress, and had a tiny, tiny waist. I learned about Harriet, the woman, the inner person, and what she was like.

KDThat reminds me of Toni Morrison’s beautiful essay “The Site of Memory.” She writes about the history of Black folks writing in this country, where the start of it was the slave narrative. When you think about Morrison, Saidiya Hartman, and the role of writers and artists—we’re all innovating from truth and fiction and blurring it together with our imaginations. You gave Harriet a vivacity that is diffused in the photograph of her; that kind of interiority is so fantastic.

LMHow much of your work is planned ahead and how much is intuitive?

BBThe only thing that I plan is selecting the photograph. The rest of it comes together as I’m working. I’ve tried to plan ahead, but without much success [laughs]. I have someone who assists me with binding and reviewing the overall composition once it’s finished. For the Tubman piece, I meditated on what needed to be said and what I wanted to integrate into the dialogue with and about her, as well as that of the photographer. I’ve found my voice through that.

LMYou capture people’s likenesses in such different ways, yet for both of you the gazes of the figures in your compositions completely lure in the viewer. It feels as if the figures you depict are staring at or even judging the viewer, as opposed to the viewer voyeuristically looking at them.

KDI took a photo class in grad school that opened my perspective and helped me introduce movement and orientation to my works. Sometimes we have interactions in which we’re returning a gaze to the thing or the person in front of us, and at other times we only see things skewed. Some images are resolved, and others are very blurry and unrecognizable. Having that range is crucial for my work, since there is never one singular way of visualizing, seeing, or engaging with someone.

BBI also think about the gaze and multiple angles when choosing photos of people who are long gone. I prefer photos where the subject is looking at me because I can only work from one image and it allows me to extract as much as I can from the content.

LMWhat are you currently working on, if you don’t mind me asking?

KDOh, my gosh—a few things. I’ve been using a printmaking process called chine collé to make use of my unused photographs. I get the image digitally printed onto a thin Japanese tissue paper called gampi, which I then adhere onto another paper with wheat paste glue as I emboss the plate’s edge using an etching press. Creating these chine collé images is a key part of my process, and it feels more ethereal than just making digital prints.

I’ve also been working with reliefs, which stems from my interest in Egyptian and Mesopotamian art, by creating embossed drawings. Instead of writing text in repetition and layering it, I impress the text into the paper and then rub the paper to render the image. I’ve been thinking of the embossment as a mark that’s only visible to us because of its shadow, which depends on the location of the light source. From afar, you can’t even tell that there’s text, and when you see the figure, it looks like an interference. As you get closer, the figure dissolves and the text becomes most legible where the rubbing is the darkest. Thinking of black as revealing or illuminating has been exciting when making these drawings.

Lastly, I’ve been making paper-thread weavings, where I write on paper, process it into thread, and then weave with it, as we discussed earlier. When I was in Ghana last summer, I brought threads that I’d made. I worked with a kente weaver who wove a pattern with my threads. The additional text that’s embedded in my thread adds another layer of encoding that not many viewers know about, but there’s a level of recognition for people who are familiar with the patterns.

BBAnd maybe viewers are not aware that they’re being affected by the resonance from the words that you wrote on that piece.

KDYes, absolutely.

BBWith all this time of isolation, I’ve reconsidered how I’ve always marveled at the past, with the abolitionists, the freedom fighters, and civil rights activists. As we were thrust into this time, it made me cognizant that I should be looking at my subjects and thinking about the importance of recording what’s happening firsthand.

LMDo you think differently about the photographs that have a singular figure versus the ones that have multiple figures?

BBI definitely do. I finished a large piece based on the Harlem Hellfighters, which was a World War I unit of Black and Puerto Rican soldiers from New York. I believe there were over three hundred men in the regiment. The quilt took forever, because there are nine men in it and it measures 9 by 13 feet. Usually, in a group composition, each person doesn’t have to have the presence or fortitude to be able to stand alone, but in this case each member was identified by name and I felt compelled to invest as much as I could into every soldier. The Hellfighters have been utterly ignored and forgotten, unlike the Tuskegee Airmen or other veterans. They won the Croix de Guerre, which is the highest military honor in France, but they only just received the US Congressional Gold Medal in September 2021, after a hundred years of zero recognition. I felt the gaze of the men warning, “I know you’re not about to do me like this. I want the full Tubman treatment, thank you.” [Laughter]

KDDon’t they speak to you, though?

BBThey do.

KDThe work communicates. We as artists become the work’s first audience, because we’re sitting there with it as it comes into being.

BBYes. I’d think about how these men are great-grandfathers and I’m looking at them when they were young; the energy is all there and they’re looking right at me. I’d start imagining things, like what their voices would sound like. They have heavy equipment and are leaving Paris. It’s winter. They’ve got big wool jackets on and medals. I could almost hear the clinking of the medals and their boots. They are on a large warship, arriving into the harbor to march down Fifth Avenue in New York.