Camille Morineau is a curator and art historian specializing in women artists. Morineau was senior curator of contemporary art at Centre Pompidou, Paris, for ten years, and in 2014 cofounded the association AWARE (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions), which aims to make visible the work of nineteenth- and twentieth-century women artists through research and publication. Photo: Valérie Archeno

I.

I had the opportunity to visit La Ribaute in the summer of 2020, before it opened to the public, during which time I saw works from the Extases féminines series (2013–15) there, and then again in the summer of 2021. During this second visit, even though I was prepared, I was caught off guard. I am still at a loss for words to describe this place, which corresponds neither to the familiar feeling of a studio, nor to the more unusual experience of wandering onto a site produced by an important artist. The first of Anselm Kiefer’s “studios/works”—a former schoolhouse in Walldürn-Hornbach, in the Odenwald region of Germany, where he worked between 1971 and 19821 —was conceived at the same time as similar projects by other artists. Two such large-scale sites/works come to mind: one, Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden, in Capalbio, Italy, which is baroque and narrative in style; the other, Donald Judd’s understated and minimalist Marfa. In this way, a generation of artists would give shape to its frustration, both with institutions and with a concept of public art that was becoming exhausted. Judd summed it up in 1985: “Nothing existing now, despite the growth of activity in museums and so-called public art, is sufficiently close to the interests of the best art. Museums are at best anthologies and ‘public’ art is always adventitious.”2

Kiefer’s first studio/site in France does not position itself as the last—his project in Croissy, even larger, does not seem to be the artist’s “final word” on his work’s hold on an enormous space either—but as one that generates specific content with its opening to the public this summer. That the artist devoted himself to La Ribaute and chose to relocate there, beginning in 1992, is as important as his decision to leave this site and open it to the public. Because, according to Jewish thought, something to which he often refers in his work and writings, the creator vacating their creation makes room, as they depart this world, for its destruction but also its creation.3 The visitor is the missing link that brings the site alive, the magical spark that will transform lead into gold, for someone who often describes himself as an alchemist. A visit to La Ribaute is performative: we “act” in a partially written play that awaits us.

Each visitor will have their own view of La Ribaute, their own interpretation, but they will all experience the same vertigo; despite the immensity of the site, La Ribaute is not known as a work, but rather as its detail, one we simply have the right to see up close and in a state of extreme intimacy. This detail comes to life over the course of the visit, like a cell that, activated by the mere fact of being discovered at the end of a microscope, might, in and of itself, “speak” of an even larger whole. One might be tempted to want to read and understand the whole, but the artist discourages this: “It is a mistake to believe that everything I have learned or read should be examined. This isn’t necessary.”4 The experience is primordial: too big to be simply looked at, too dynamic to be browsed, too dense to be read definitively, La Ribaute is to be lived. Transitive, it transforms.

The artist himself continues to be transformed by the site, which remains a place of inspiration and reflection: “You sit at the north end of the room, with a view overlooking the Cévennes, and you write. You would love to see what Celan’s language hides. Here, in front of the view of Aubrac, where the Huguenots took shelter after the night of the Saint Bartholomew’s massacre, you hope to find the key to the letters indicated by the poet.”5

a site that allows those who traverse it to understand that the future can lead to the past, and not the opposite.

The opening of this previously secret site plays precisely on the site’s secret nature, for those who know a bit about French history. Located within the Cévennes, land of the Huguenots and the Resistance, and of the Cathar siege during an older and more radical but equally bloody religious and philosophical rebellion, Barjac is in a “European-style” desert. Not as empty and geologically defined as a desert in the United States, but difficult to reach and far from town centers; one of those places constructed of shelters where rebellions have been fomented. Religious, philosophical, and political, these deserts are often craggy regions of thought. Instead of geological strata, historical, cultural, and above all spiritual layers are superimposed there. Battles have been fought in the shadow of rocky ridges or at the summits of peaks unknown to one’s enemies, and/or to practice a religion or develop political or philosophical ideas of resistance. La Ribaute is one of these deserts, sometimes more metaphorical than real, where certain thinkers such as Kiefer—fighters, religious figures, philosophers, or writers—have simply withdrawn to work out a counter idea: an idea about the periphery versus the center, an attempt at communal living versus a totalitarian society, practicing a gnostic or esoteric mystique rather than a religion . . . in short, a “Protestant” way of thinking.6

Kiefer often corrects his interlocutors who confuse Barjac with Provence and its touristic and artistic inflections. Nothing but sunflowers connect it to the land of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cezanne, however near it is as the crow flies. Nor will it be, for him, a question of representing this “desert” and the nation that houses it, as Georgia O’Keeffe used New Mexico to define an “American art.” By settling down in Barjac, Kiefer fled and rebuilt: his work, particularly painting, his materials in general, but also himself. He established himself in Barjac gradually, while also traveling the world. In this desert and this suspended time, he went on to implement his vision of inversion: a site that allows those who traverse it to understand that the future can lead to the past, and not the opposite. That the spiritual and the material merge.

II. Women in Barjac: The Women of the Revolution and the Reversal of History

A visit to La Ribaute is an initiation, a rebalancing: between the human and the natural, architecture and chaos, vertical and horizontal, religious thought and gnostic thought, science and alchemy, past and future, horizontal and vertical. However, I would like to dwell on the resolution of contraries that I least expected when I visited, because I hadn’t found them in any book on Kiefer: the masculine and the feminine.

Military planes, naval battles, piled-up bunkers, the heroism of gestures and the theatricality of places, the recent homage to Paul Celan in the Grand Palais Éphémère in Paris: at first glance and from afar, Kiefer can be read as masculine, I thought. Visiting La Ribaute, however, whether in sunlight or in the shadow of the tunnels, I understood that against all expectation and all logic, it is the feminine that has triumphed—that if La Ribaute is an emblem for the transformation of the world, it has to be seen as, among other things but also primarily, a compelling invitation to put women at the center and thus a rather implacable demonstration of their power. It didn’t take long to find confirmation from the artist himself. In the short text entitled “Barjac,” taken from classes given at the Collège de France between December 2010 and April 2011, Kiefer describes two underground chambers in the conclusion. The walls of the first, he explains, “are scored with the teeth of the digger’s bucket, which resemble the claw marks of a very large bear.”

I have in mind here a scene from Kleist’s Battle of Arminius, in which Arminius’s wife Thusnelda, who is being wooed by the Roman legate Ventidius, lures the latter into a pit, where he is mauled to death by a bear. . . . Thusnelda’s vengeance . . . the name Thusnelda has always been charged with a portentous, ambivalent significance, even up to this day.

This room leads to a second underground—and more roughly built—chamber. Dedicated to the Women of the Revolution, it contains lead beds with puddles of water stagnating in their hollow spots. . . . The water is now out in the open and its surface, visible through the dust, is again like a skin, a membrane, a boundary between the inner and the outer; a metaphor for the tremendous power that women draw from deep within themselves in contrast to the superficial bluster and bragging of men.7

This work was among the first to be installed within the network of underground tunnels at La Ribaute (the central, historic tunnel bears the name of another woman, Eurydice), which very effectively bring about an experience of inversion for the visitor: between above/architecture and below/chaos, between past and future. It is not as an activist but as an informed, indeed erudite, historian that Kiefer positions himself. “It is in the salons of Mme. Roland, of Mme. de Staël, that new ideas of social upheaval were forged; I erected a monument to them, referencing Jules Michelet, who I read enthusiastically when I was young,” he soberly explains in regard to the installation Les Femmes de la Révolution.8

This “monument” dedicated to exceptional women, to whom Kiefer attributes the Revolution rather than to men, reminds us that La Ribaute is a site of memory: not only of the artist-custodian’s work, the mark of which it bears, but also of the accounts that the artist-historian transforms, giving them back their shape. His alchemy ties myths, stories, and History (with a capital H) . . . to the feminine. From 1992 to 2007, during which time he secretly developed the gigantic work of La Ribaute, one sensed in his works that could be seen elsewhere a feminine and possibly feminist rereading of some of the great narratives that interest him: the histories of France and of Germany, philosophy and contemporary poetry, biblical and other religious accounts, antiquity and myths. Reintegrated into La Ribaute, certain of these works, at times ancient or copies of ancient works, whether they lie at its center, at its extremities, or in series, such as the towers (Die Himmelspaläste, 2003–18) or the dresses/busts (Die Frauen der Antike, 1999–2002; Femmes martyres, 2018–19), offer spatialized examples: the visit is a device of conviction.

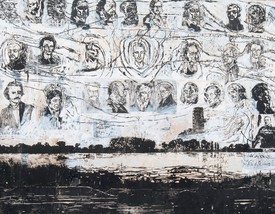

They assert themselves as evidence, this army of women composed of white dresses cinched at the waist, open at the upper body, inspired by the nineteenth century or bridal gowns, their heads taking the form of objects/symbols. They are found at the center of the site—four resin busts covered with symbols stand in the amphitheater that is the “heart” of La Ribaute—and compose the most recent creation: a hill where one discovers some twenty of these metaphorical busts, more or less hidden, as one gradually ascends the slope. They symbolize fields of creation (literature, painting, architecture), power (freemasonry, politics, philosophy), allegories (justice, equality, etc.), mechanical inventions that have been attributed to men (cinema, trains, planes, etc.); these headless women are in reality in charge of the world. Their titles are in the process of attribution, and this vagueness indicates that it is likely or desirable for visitors to be able to envision whatever they like. This hill writes a history in reverse, where women are at the origin of certain inventions in particular, and of creation in general. Each functions as a chrysalis, the visitor’s gaze bringing forth a strong woman from this open form.9 Each plays her role in the utopian history that emerges at La Ribaute. Contrary to male-dominated public space—where the vast majority of streets bear the names of men, where public sculptures signed by men pay homage to men—here 100 percent of the busts are female. At the top of the hill, a palette takes flight like a giant butterfly. The history of La Ribaute was built with and beginning with women: Cornelia (1995), one of the oldest sculptures on the site, pays homage to this Roman woman, remarkable for having educated her children as a principle above all others. At La Ribaute, the Medusan voyager remakes History beginning with heroines, rather than heroes.

III. Women of Antiquity, Queens of France, Witches, and Counter-Narratives

These numerous busts are scattered along a labyrinthine path like Ariadne’s thread, where titles, when they are names, are for the most part those of women. La Ribaute, as in the artist’s work overall, pays particular homage to some of them. Die Frauen der Antike, installed in one of the first greenhouses to be constructed on the site, is a response to the underground Femmes de la Révolution. As early as 1999, Bernard Comment described the semantic complexity of this series, one version of which was exhibited at Yvon Lambert in Paris that year.10 Noting that “the concealment of the feminine in the History of Mankind had already been at the heart of other series”—citing both Les Femmes de la Révolution and the book Les Reines de France (1996)—Comment underscores the importance in Kiefer’s work of these “non-residents of History or mythology” and explains Kiefer’s interest in these accounts that never happened: they “thus allow complete freedom to invent them.” Their placement in a greenhouse augments the power of transformation of this latent liberation: “The glass planes constitute a semi-permeable skin, so to speak, linking art to the world outside. . . . The more pressingly the artwork confronts the boundary between art and life the more interesting it grows. The glass skin of the greenhouses is such a frontier, the object of a tug of war.”11

Two women writers appear pivotal to Kiefer’s rereading of European poetry and philosophy; they are well represented in his oeuvre and very significant at La Ribaute. Ingeborg Bachmann is less known in France than Paul Celan, who was both her correspondent and her lover, but at least as important for Kiefer. Well-known from the age of twenty-eight, when she had already appeared on the cover of Der Spiegel, Bachmann was only forty-seven at the time of her tragic death in 1973. She left behind thousands of unpublished pages, a novel, a number of poetry collections, short stories, and a philosophical work. She shared with Kiefer both the experience of living with guilt for Nazi crimes—her father served as a Nazi soldier—and a passion for the oxymoron as a liberator of meaning. This is summarized in the title of the collection dedicated to her in the “Poésie/Gallimard” series, Toute personne qui tombe a des ailes (Everyone who falls has wings).12 Kiefer soon devoted a pavilion to her: Für Ingeborg Bachmann, nur mit Wind mit Zeit und mit Klang (1999–2003).

Another female figure cited at La Ribaute—as well as in the rest of Kiefer’s work—is Madame de Staël, who, in his paintings, often occupies a more central position than a number of better-known German philosophers.13 Specific homage is paid to her in the pavilion housing a group of engravings on wood.14 She is less known in France than her lover Benjamin Constant, despite having published three critical philosophical essays during her lifetime.15 Supportive of the French Revolution, she had been forbidden by Napoleon from setting foot on French soil but went on to hold a famous salon in Paris. Thanks to this, and to the publication of her essay De l’Allemagne (Germany, 1810), she popularized German authors and opened the way to French Romanticism.16

At the other end of La Ribaute, a forest or city of towers—Die Himmelspaläste (2003–18)—is inhabited, according to the artist, by Lilith,17 another central figure in Kiefer’s female pantheon. The artist has paid tribute to Lilith—a witch to some people, a female savant to others, frowned upon by all—since the 1990s, and her black hair adorns a number of his paintings. Lilith is the woman we fear but also the woman who knows, a symbol of one who is persecuted in the end. Art historian Matthew Biro describes the emergence of this figure in Kiefer’s work beginning in the 1990s,18 after the Margarete and Sulamith paintings of the 1980s, inspired by a poem by Celan. Prior to this, as early as the 1970s, other historical figures, such as Brunhild or Elisabeth of Austria, had appeared in his work. Biro rightly emphasizes the dialogue between the artistic director of opera and the sculptor in the installation of the immense towers/ruins and the busts/metaphors: Kiefer has previously deployed these two elements as opera sets/characters.19 The performance/image of the Trümmerfrau, as the women who cleared away ruins before rebuilding homes in the aftermath of the war are known, is also a recurring figure in his work. This figure appeared in 1991,20 at roughly the same time as his move to Barjac, in a key performance in which the artist is walled up by women. It is an enactment of the myth of Antigone with the genders reversed: male is enclosed by female, past by future. Kiefer evokes a patient, deliberate reconstruction of the world by women.21

With these names/citations/injunctions placed at its critical points, La Ribaute can be experienced as the transformation from a history where women have been forgotten to a narrative that glorifies them, an account of women’s physical and spiritual courage throughout the centuries, their creativity in all realms, but also their cruelty. Much as one might admire them, Kiefer summons up the terror that they may have inspired as much as that of men. Art historian Dominique Baqué recently recognized in Kiefer’s work an homage to women of anger and rebellion. Kiefer, she writes in the 2015 volume Anselm Kiefer: Entre mythe et concept, “is passionate about women. He attributes them with strength, willpower, intelligence, and a great capacity for disobedience. With the possible exception of Paul Celan, there are no such male figures in his paintings. These women are constantly confronted by the turmoil of history; they are assaulted, sacrificed, slaughtered. Yet while history has never been gentle on them, it often obscures them.”22

IV. “At any moment what you see here may trigger a flashback”

A year later, in 2016, the publication of Kiefer’s first volume of notes added to this edifice, describing the construction of the series of metaphorical busts that characterize the Barjac site. Contrary to what Comment might have imagined, they were constructed from a verified genealogy. In February 1999, having returned from a trip to India and considering himself installed in Barjac, Kiefer describes its tale of women of antiquity, where the most famous exist side by side with those who are lesser known. Notably, he breaks down the identified groups (Sibyls, Sabines) into an enumeration of the mythical or real figures who constituted them; women of mythology are added to women of power, monsters to saints, wives to Amazons, resulting in an impressive alphabetical list composed of eighty-six entries.23

Each name is followed by a brief account, from a few lines to a paragraph long, ending with a technical entry: whether a “portrait” or an attribute that evokes a sculpture/installation. The journal describes this hesitation between painting and sculpture, then his abandonment of painting in favor of a series of dresses, first in plaster, then in resin, where the heads/attributes will be simultaneously precise and poetic: “it should all be much more expansive. no anecdotes, suggestions rather than allusions.” In May 1999 the series is defined: rather than painted portraits, he decides on the form of a metaphorical sculpture consisting of a dress/bust where the folds speak for themselves: “folds are always evidence that something has disappeared, vanished, the way the folds in sheets on a bed that’s still warm in the morning hint at bodies now gone.” These dresses/busts are cast from typical dresses—all monochrome but, like the rest of his work, subjected to traces of rust or time—surmounted by objects. The balance between concept and incarnation is achieved by a certain choice of material: barbed wire, for example, rather than thorns, “is both more abstract and more concrete.”24

In this magnificent notebook, where day after day his work is constructed, one finds the poet but also the scholar, and finally the virtuosic artist of materials. Kiefer, of course, plays with connections, but they are informed. The artist-historian seems determined to overturn the course of history, employing a strategy that is both artistic and scientific:

now all the [women] who seem interesting are written down. who is interesting? probably only those for whom you have a painting in mind. not only. which others as well? those who stand out for their cruelty, for being particularly monstrous. not because of monstrosity per se, but because a particular quantity or a particular brand of cruelty creates legends, sticks them in the memory like a flood or an earthquake.

something egregious must happen, something people will recount for a long time, and by force of repetition it solidifies into a myth that is carried through time without losing anything.25

Alive, powerful, incarnate, the women in Kiefer’s work traverse the centuries more effectively than men.

The genealogy of this history of male/female inversion and/or the permeability of genders is consistent with another profound admiration on Kiefer’s part: one he has felt for Jean Genet since 1969. And so let us return, as La Ribaute invites us to do (“at any moment what you see here may trigger a flashback,” Kiefer writes).26 In his course at the Collège de France, Kiefer talks about his proximity to the poet—their works sharing the power to reverse time,27 the desire to construct a legend,28 the faith in poetry’s magical power. At the start of Kiefer’s fame, the celebrated series Besetzungen (1969) coincided with the artist’s book für Jean Genet (1969), where, dressed as a woman, he pays homage for the first time to Elisabeth of Austria, Madame de Staël, and Mariana Alcoforado. The flowered dress he wears as a performative “disguise” in this foundational series is the same one that coexists with the military costume in his Besetzungen series. Yet this female “attribute” is almost never noted or commented upon.29 Much has been written about his geographical occupation of Europe as a Wehrmacht soldier, whereas his cross-dressing as a woman in the studio remains invisible, as if hidden. However, these two examples of “cross-dressing/inversion” seem to me to participate in the same rebellion against invisibility—against the rendering invisible of a dark period in German history, against the profound oversight of women in history. Because this complex performance lies at the origin of a complex oeuvre, it is difficult to summarize its implications in a few words. Let us simply recall that it plays a role in a comprehensive homage to Genet, who chose theft, crime and his love for men being the same love for the evil whose beauty he celebrated; Genet, who confused his love for flowers with his love for men; Genet, whose work was not based on the inversion of good/evil and woman/man, but on the demonstration of their permeability, this confusion being the creator of beauty; this “legend” who conflated his “poeticized” life and his work.

La Ribaute is also an immense site for the celebration of permeability: between art and life, lead and stone; a celebration of the feminine and the spiritual rather than the bravado of construction; of ruin and dispersal rather than construction and solidification; of membrane and margins rather than wall and land. In this way, an opposition is drawn between a rereading of the feminine and the masculine, where the latter yields, where Kiefer equally brings into play stereotypes of history and those of art and architecture, as much as the tropes of his own legend.

Alive, powerful, incarnate, the women in Kiefer’s work traverse the centuries more effectively than men, to the point of allowing the final transformation, which is also the oldest historically: the erasure of men, including the artist, and his transformation . . . into a woman.

1Danièle Cohn describes this new type of work by the artist—studios/sites/places for performance—beginning with La Ribaute, in her Anselm Kiefer: Ateliers (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 2012), pp. 35–51.

2Donald Judd, “Marfa, Texas,” in Donald Judd, Écrits 1963–1990 (Paris: Daniel Lelong Éditeur, 1991), p. 176; Donald Judd Writings, ed. Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2016), p. 430.

3In one of the readings of the Kabbalah that fascinates Kiefer, the beginning of the world is the moment where God must step aside. This is clarified in numerous texts, among them: Marc-Alain Ouaknin, “La Kabbale et l’art de la bicyclette: Anselm Kiefer et la mystique juive,” in Jean-Michal Bouhours, ed., Anselm Kiefer (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2015), pp. 28–43.

4Kiefer, interviewed by Alexander Kluge, in Anselm Kiefer in Barjac, dir. Walter Smerling (White Cube, 2020).

5Excerpt from Anselm Kiefer’s journal, June 28, 2021, 3:11 p.m.; see Anselm Kiefer: Pour Paul Celan (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, Grand Palais, 2021).

6Indeed, in the eighteenth century mention is made of “shepherds of the desert,” but other great philosophers withdraw into these “European deserts” to develop new ideas. Descartes goes into exile in Holland and proclaims, “I thought I had to try by every means to become worthy of the reputation that was given me. Exactly eight years ago this desire made me resolve to move away from any place where I might have acquaintances and retire to this country, where . . . I have been able to lead a life as solitary and withdrawn as if I were in the most remote desert.” René Descartes, “Discourse on the Method,” in The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, trans. John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), vol. 1, p. 126. I am grateful to Henri Salha for this quotation.

7Anselm Kiefer, “Barjac,” in Anselm Kiefer au Collège de France: L’art survivra à ses ruines/Art Will Survive Its Ruins (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 2011), p. 336. Les Femmes de la Révolution was first exhibited in the form of an installation at Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, in 1992 and rebuilt numerous times prior to its installation at La Ribaute in 2006.

8Kiefer, interviewed by Kluge, in Anselm Kiefer in Barjac.

9The plaster garments that are placed there were installed to animate a 2003 production of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, for which Kiefer designed the sets and costumes. The singer withdrew herself from a sculpted garment, like a butterfly from a chrysalis.

10Bernard Comment, “Un art allusif,” in Anselm Kiefer: Die Frauen der Antike (Paris: Éditions Yvon Lambert, 1999).

11Kiefer, “Barjac,” p. 333.

12Ingeborg Bachmann, Toute personne qui tombe a des ailes (Poèmes 1942–1967), trans. Françoise Retif (Paris: Gallimard, 2015).

13Her name is often inscribed in the works dedicated to her, appearing in a central position, with the names of Hegel, C.G. Jung, and Heidegger half-hidden in the folds of the painting, on a lower frieze.

14This group, entitled Der Rhein (1982–2013), was recomposed at La Ribaute beginning with the engravings on wood that had made up the installation presented at the Musée du Louvre, Paris, in 2013, in the exhibition De l’Allemagne: De Friedrich à Beckmann. The title of the exhibition reprises the title of an essay by Madame de Staël, to which Kiefer also refers in this group.

15Lettres sur les ouvrages et le caractère de J. J. Rousseau (1788), De l’influence des passions sur le bonheur des individus et des nations (1796), and De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales (1799).

16She also published fiction that represents women as victims of social constraints that enchain them, including Delphine (1802) and Corinne, ou l’Italie (1807).

17Kiefer, interviewed by Kluge, in Anselm Kiefer in Barjac.

18Biro describes how the motif of the dress moves from painting to sculpture, from a connection to Lilith in the 1990s to a dress/metaphor series, and finally to a dematerialized Lilith as the inhabitant of the towers (originally The Seven Heavenly Palaces and now, at La Ribaute, a “city” of some fifteen towers). Matthew Biro, Anselm Kiefer (London: Phaidon, 2013), pp. 108–09.

19In addition to creating the set designs for two operas in 2003 (in Naples and Vienna), in 2009 Kiefer presented the production Am Anfang (In the Beginning) at the Opéra Bastille, Paris. Here the Seven Heavenly Palaces (towers similar to those employed in the site-specific installation of this name at Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan [2004–15]) served as the set for a performance where the main characters are women who sweep away dust, an evocation of the Trümmerfrauen Kiefer saw in his childhood.

20The figure of the Trümmerfrau appeared for the first time in 1991, at the brickworks in Höpfingen, Germany. See the documentary Anselm Kiefer: Operation Sea Lion, dir. Christopher Swayne (BBC, 1991).

21“Chronology,” in Bouhours, ed., Anselm Kiefer, p. 256.

22Dominique Baqué, Anselm Kiefer: Entre mythe et concept (Paris: Éditions du regard, 2015); Anselm Kiefer: A Monograph (London: Thames & Hudson, 2016), p. 114.

23Anselm Kiefer, Notebooks, Volume 1: 1998–1999, trans. Tess Lewis (London: Seagull Books, 2016), pp. 299–318.

24Kiefer, Notebooks, pp. 319, 329.

25Kiefer, Notebooks, pp. 317–18.

26Kiefer, “Barjac,” p. 329.

27Kiefer devotes a chapter of his course at the Collège de France to Genet: “Genet, Nietzsche, Oussama: L’art peut-il être conciliable avec la vie? / Genet, Nietzsche, Osama: Can Art and Life Be Reconciled?” in Anselm Kiefer au Collège de France, pp. 47–70, 213–38. Genet says of his own journal: “It is not a quest of time gone by, but a work of art whose pretext-subject is my former life. It will be a present fixed with the help of the past, and not vice versa. Let it therefore be understood that the facts were what I say they were, but the interpretation that I give them now is what I am—now.” Genet, The Thief’s Journal, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: Gove Press, 1964), p. 71.

28Genet, The Thief’s Journal, quoted in Kiefer, “Genet, Nietzsche, Osama,” p. 218: “My life must be a legend, in other words, legible, and the reading of it must give birth to a new emotion which I call poetry. I am no longer anything, only a pretext.”

29For commentary on Kiefer’s cross-dressing, see Bouhours, ed., Anselm Kiefer, and Baqué, Anselm Kiefer: Entre mythe et concept.

Translated from the French by Marguerite Shore

Artwork by Anselm Kiefer © Anselm Kiefer