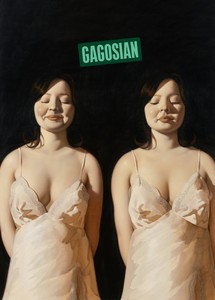

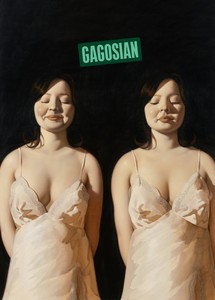

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Winter 2022

The Winter 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Anna Weyant’s Two Eileens (2022) on its cover.

Winter 2022 Issue

The definitive monograph on the work of Walter De Maria was published earlier this fall. To celebrate this momentous occasion, Elizabeth Childress and Michael Childress of the Walter De Maria Archive talk to Gagosian senior director Kara Vander Weg about the origins of the publication and the revelations brought to light in its creation.

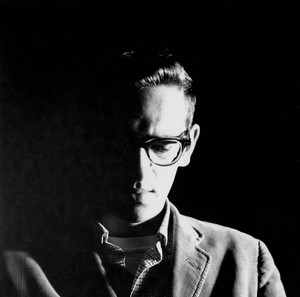

Walter De Maria, 1961. Photo: George Maciunas

Walter De Maria, 1961. Photo: George Maciunas

Kara Vander WegElizabeth, when did you first meet Walter De Maria?

Elizabeth ChildressI first met Walter at The Lightning Field [1977] in 1978; I was there with my boyfriend, John Cliett, to photograph lightning storms over the field. We were good friends with Robert Fosdick and his wife, Helen Winkler, one of the founders of the Dia Art Foundation. They were working closely with Walter at The Lightning Field, developing a program for visiting the sculpture. Dia was a huge supporter of Walter and his work at the time, providing spaces and funds for major projects but also providing artists with assistants and archivists. They really did so much to make it possible for Walter to make his work, which was often quite complex to create, install, and maintain.

Anyway, we became a bit of a family. By the end of that summer, after leaving The Lightning Field, Walter asked me to be his assistant and help him organize his studio in SoHo. Then I was approached by Heiner Friedrich, the German art dealer who founded Dia in 1974 with Philippa de Menil and Helen. Heiner thought that it would be great if John and I could work on more photographs of The Lightning Field. We went back in the summer of 1979, and when I returned to New York, Heiner set me up with an office in part of the New York Earth Room [1977] gallery and I started working with Walter on a regular basis. This primarily entailed establishing an archive and working with him on his new projects. Eventually we moved over to his building at 421 East Sixth Street in Manhattan and over the years I continued to work with him on many projects, until he had a stroke in 2013.

KVWAnd your work has continued, because after his death, you were responsible for archiving the entire studio.

ECYes. Because Walter died quite suddenly, none of us were prepared. Walter had work that was not completed. He had an enormous building full of art that we had to inventory. He had worked, for nearly thirty years, on the Truth/Beauty series [1990–2016], and we were able to complete that with the support of his family and the gallery. That was huge. The gallery, in addition to Dia, was really important to Walter, particularly toward the end of his life. And after he died, you and the gallery were so supportive—it made the whole process so much more structured. And you worked closely with Walter’s family to make a plan, and that was ideal, because Walter never established a foundation.

Walter De Maria, Truth / Beauty, 1990–2016, solid stainless steel and granite, 14 sculptures in 7 sets, each sculpture: 7 ½ × 42 ⅛ × 42 ⅛ inches (19 × 107 × 107 cm). Installation view, Walter De Maria, Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, May 26–July 30, 2016. Photo: Mike Bruce

KVWLarry Gagosian began working with Walter in 1989, and from the very beginning he saw the importance of the work. Over the years, he saw that, as is often the case with artists, consistent support makes a big difference in terms of their careers and legacy, so whenever he could he would support Walter in that way and allow him some leeway. It was Walter’s exhibition that inaugurated the Thompson Street gallery that Larry operated with Leo Castelli.

Michael ChildressAnd during our research we discovered that after his first show with Larry, Walter never showed with another private dealer again. He had plenty of institutional recognition and exhibitions, of course, but his only gallery representation after that moment was through Gagosian.

KVWAnd then there were the New York shows we worked on together in 2007: 13, 14, 15 Meter Rows [1985], on Twenty-Fourth Street, and A Computer Which Will Solve Every Problem in the World/3–12 Polygon [1984], on Twenty-First, which belonged to the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam. We borrowed it back from the museum because it was important for Walter to show those two objects together and to have that circle completed, so to speak.

ECWhen did you first meet Walter, Kara?

KVWI first met Walter in 2005, a year after I started working for Gagosian. Larry told me to call Walter De Maria and see if he wants to do anything in any of our spaces. And I think I called for about, I don’t know, a couple of months, and he would just hang up—the phone would ring and then he would hang up [laughs].

EC[laughs] What? No.

KVWHe thought I was a real estate agent trying to sell the building. Eventually I sent a fax saying, I’ve always admired your work. I love the Earth Room, I love the Broken Kilometer [1979]—both of those installations are meaningful to me. Then he called me up and said, “Hello, this is Walter De Maria” [laughs]. So that was my introduction to Walter.

ECIt would always take Walter a little bit of time to feel comfortable and trust people. But you were one of those people whom, eventually, he really did.

View of Walter De Maria lying on the desert floor touching one chalk line of Mile Long Drawing (1968). Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

KVWWell, I appreciate that trust. That for me was why it was important to try to make a book about his life and work. It deserves such a publication and I think it’s crucial in terms of memorializing that material and informing people going forward; there’s a paucity of information on Walter’s work out there. Additionally, because we’re able to coincide with the exhibition taking place at the Menil Collection in Houston, which includes so much of Walter’s early work [Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work, October 29, 2022–April 23, 2023], the timing feels particularly appropriate.

Michael, maybe you could talk about how you became involved with Walter’s work, and specifically about all the great work you’ve been doing on the monograph and the archive.

MCI grew up knowing him, but only on the phone, really. But when he had to prepare the second floor for the Bel Air installation at the Menil Collection in 2011–12, I came by the studio and worked with him going through a lot of the material that was being stored there on the second floor, and moved it up to the fourth floor in preparation for the restoration turning the second floor into a gallery space. It was fortunate that we had that time together because two or three years later, when Walter died, I came down to go through that material that I’d only just moved, and to figure out what it was that we had just gone through. Later we began the process of analyzing and initiating the database project, with the goal of eventually producing the monograph.

KVWAnd can you describe what the database project is?

MCEverything was well organized in its physical form, but after the move, we realized that we needed to have a digital system with which to access the material. When we were looking for a database, we found a system that was specifically focused on making a catalogue raisonné. From there, we started entering the data from the office, setting up a base that we could use to make the book.

KVWWere there any surprises in the book that arose as you were putting this material together?

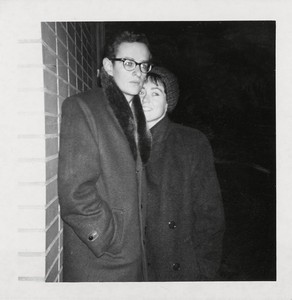

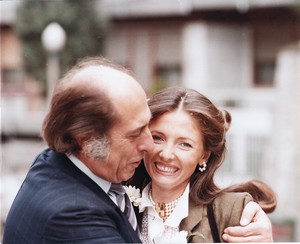

Walter De Maria and his wife, Susanna, in New York, c. 1961. Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

ECThe most extraordinary moment was when we first created a timeline. We had images for each of Walter’s works, with the dates, and we laid them out according to their chronology on side-by-side panels across three long tables. I had never viewed his work from that perspective before; when you’re working in it, you’re not thinking about the timeline. Seeing the evolution of his career, and recognizing early moments that foreshadowed later major works, was something of a revelation. And that carries through into the finished monograph.

Also, all of Michael’s work with the drawings and studies provided so much more information about Walter’s process, especially in the early 1960s.

MCPicking up on these arcs in Walter’s work, being able to see the echoes of his early work in later projects—that’s something that wasn’t possible before.

KVWI love looking at some of those early drawings and seeing, as you were saying, the early ideas that he was developing, even the early iterations of The Lightning Field. And I love seeing Walter’s hand in these works, because when I knew him, the work had been developed to the point where it was all so well-produced, milled—it was perfect. But with these drawings and studies you really get a sense of the person behind the work.

ECAnd his sense of humor!

KVWOh God, yes.

MCThe drawing that we always use as an example is Untitled [Large Ball in Small Room] [c. 1959–62]: to know that he was thinking about that in reference to Michelangelo’s David, all delineated on the same page, was revelatory. His interest in art and architecture from the very beginning opens new ways for experiencing the work. Also, the essays in the monograph, by Donna De Salvo, Michael Govan, Christine Mehring, and Lars Nittve, all elucidate different aspects of his work.

KVWHe had such an interest in current events, which I experienced in my conversations with him between 2004 and 2013. He would bring up events that he had seen on television, sporting events, that sort of thing. But in those early drawings, where he writes about the death of JFK or the Cuban missile crisis, you realize that all these artworks, all these steel sculptures that appear to be straightforward abstract geometric forms, have all this content behind them in some way.

ECHe was a history major.

KVWThat was really the topic of every conversation.

ECI think we must have had subscriptions to about twenty-five magazines. Walter read everything.

Walter De Maria framed by The Arch (1964) in Walker Street studio, 1964. Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

KVWAnother part of the book that will be a discovery for people is the chronology, written by Dagny Corcoran but of course the two of you were editing, supplying illustrations, and connecting her with the right people. It was a delicate dance to give a comprehensive overview without violating Walter’s privacy, which he valued very much. Many decisions were required about what was applicable to Walter the man versus Walter the artist. For me, the information about the music he made, his participation in early Happenings and performances, his early family life, his friends and acquaintances—this was incredible information and often quite unexpected.

MCAbsolutely, that’s not what his reputation was. Walter was not known for being out and about and traveling a lot, but when you read this chronology, it subverts all those misunderstandings.

KVWDo each of you have a favorite part of the book? Or a project that piqued your interest in a different way when you were working on it for the book, as opposed to looking at it in real life?

MCSpeaking further about the echoes or themes that we can now pick up on because of the chronological order, or just having all his work in one place, we can see new relationships arising between artworks. For example, The Arch [1964] was the first time Walter really engaged with architecture or with an environmental installation. You see here that his “box” has increased in scale to the point where you’re no longer reaching into it, as you are with Surprise Box [1961], but actually entering and ultimately passing through it. This type of form, the corridor or passageway, is also related to his Walls in the Desert proposal [1961–64] and the Mile Long Drawing [1968]. Even his channel sculptures, such as Instrument for La Monte Young [1965–66] or Cross [1965–66], can be looked at as formally related to the passageway.

In addition to these thematic relationships, a deeper understanding of the work is achieved when looking at the development of Walter’s singular ideas over time. Many people know of The New York Earth Room as a permanent installation in SoHo, but they may not know that this was the third earth room that Walter made. Or that he later took the concept even further with 5 Continent Sculpture [1989], using white rocks sourced from mines around the world, a work relating back to his Three Continent Project proposal [1967–69].

KVWWell, I hope the Menil exhibition and this book will generate more conversation, more ideas, more books, more museum exhibitions.

ECI think that’s exactly what will happen. When we had to document many of these early works, I realized how little I knew about that period in his career, so we had to go back over and over again to make sure all of our facts were correct. Walter rarely spoke about his earlier work, so most people don’t know about it, even those who know the later work quite well.

Walter De Maria, 5 Continent Sculpture (cube installation), 1989, white stones, painted steel frame, and plexiglass windows, overall dimensions: 16 feet 4 ⅞ inches × 16 feet 4 ⅞ inches × 16 feet 4 ⅞ inches (500 × 500 × 500 cm), volume: 163.49 cubic yards (125 cu. m), weight of stones: 400,000 lb. (18,1437 kg). Installation, Mercedes-Benz Group AG International Administration Building, Möhringen, Germany, Collection Mercedes-Benz Group AG, Möhringen, Germany. Photo: Dieter Leistner

Walter De Maria, Time / Timeless / No Time: The 3-4-5 Series, 2004, Indian Green granite, mahogany, Manetti 23 ¾-kt red gold leaf, and cement, sphere: 86 ¾ inches (220 cm) diameter, sphere weight: 34,000 lb. (15,422 kg), twenty-seven gilded wood sculptures, each overall: 52 ¾ × 34 ⅞ × 10 ¾ inches (134 × 88.6 × 27.1 cm), twenty-seven 3-sided rods, each: 50 × 6 ¾ × 5 ¾ inches (127 × 17 × 14.6 cm), twenty-seven 4-sided rods, each: 50 × 5 × 5 inches (127 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm), twenty-seven 5-sided rods, each: 50 × 6 ½ × 6 ⅛ inches (127 × 16.5 × 15.6 cm), twenty-seven cement pedestals, each: 5 ⅛ × 39 ⅜ × 14 inches (13 × 100 × 38 cm), gallery: 32 feet 9 ¾ inches × 32 feet 9 ¾ inches × 78 feet 8 ⅞ inches (10 × 10 × 24 m), commissioned by Soichiro and Nobuko Fukutake for Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima, Japan. Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama

KVWNow that you’ve done this, may I ask what resources you had available?

ECThe first time I ever went to Walter’s studio, in 1978, he had this two-room setup—essentially an enormous loft, where he lived on one side and worked on the other. There was a series of about ten tables constructed out of four-by-eight sheets of plywood and sawhorses, and on each one of those tables there were piles of paper. That was Walter’s office [laughs].

KVWThat sounds very artistlike.

ECNothing was organized. So I started putting things in boxes and asking him about each piece of paper.

KVWSo forty years later, when you’re writing descriptions for the early artworks, you could go back to these boxes, find correspondence or—

ECExactly. And we were also able to access information from different European archives—one of them in particular was hugely helpful for information about the never realized 99-Sided Circle [1977], they made scans of everything they had in their files. So now, in the book, you can see some of these unrealized projects that Walter initiated when he was much younger, like the Three Continent Project, and understand what his intent was.

MCWe were fortunate that most of Walter’s work is owned by public institutions. A huge part of the initial phase was reaching out to all known owners and sending them the fact sheets that we had produced with the database and having them verify a lot of that information for accuracy.

KVWWell, I have to say, your work has made a huge difference in making available this incredible historical resource that you used to compile the monograph and that will be in the archive for the future. Do you think differently about Walter after working on this book?

MCFor me as a young artist, the opportunity to read through the notes and works on paper that he was working on at my age, essentially, was extremely rewarding. He was really going through and developing his ideas, but also encouraging himself to stay true to his vision in a way that I have found quite inspiring.

Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling (New York: Gagosian, 2022)

Artwork © Estate of Walter De Maria; photos: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

Elizabeth Childress is the director of the Walter De Maria Archive. She was De Maria’s archivist and studio manager from 1979 until his death, in 2013. She is the coauthor and editor of Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling (2022).

Michael Childress is an artist based in Northampton, Massachusetts. He began working with the Estate of Walter De Maria in 2013 and helped to establish the Walter De Maria Archive. He is the coauthor and coeditor of Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling (2022).

Kara Vander Weg is a senior director at Gagosian, New York, where she has worked for more than fifteen years. She manages a number of the gallery’s established artists and estates, among them the Richard Avedon Foundation, Walter De Maria Collection and Archives, Michael Heizer, Neil Jenney, David Reed, Richard Serra, and Mark Tansey.

The Winter 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Anna Weyant’s Two Eileens (2022) on its cover.

In this second installment of a two-part essay, John Elderfield resumes his investigation of Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977), focusing this time on how the hope to see lightning there has led to the work’s association with the Romantic conception of the sublime.

In the first of a two-part feature, John Elderfield recounts his experiences at The Lightning Field (1977), Walter De Maria’s legendary installation in New Mexico. Elderfield considers how this work requires our constantly finding and losing a sense of symmetry and order in shifting perceptions of space, scale, and distance, as the light changes throughout the day.

The Spring 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Gerhard Richter’s Helen (1963) on its cover.

The inaugural presentation of Frieze Sculpture New York at Rockefeller Center opened on April 25, 2019. Before the opening, Brett Littman, the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum and the curator of this exhibition, told Wyatt Allgeier about his vision for the project and detailed the artworks included.

Lars Nittve investigates Truck Trilogy, Walter De Maria’s last work, conceived in 2011 and premiered at Dia:Beacon in 2017.

Artist Terry Winters, longtime friend of De Maria and member of the installation crew for The Lightning Field, recounts a trip to New Mexico and the surrounding area and attests to the power—the “rhythm and pulse of ancient mystery”—that continues to imbue De Maria’s artworks into the present day.

Art for a Safe and Healthy California is a benefit exhibition and auction jointly presented by Jane Fonda, Gagosian, and Christie’s to support the Campaign for a Safe and Healthy California. Here, Fonda speaks with Gagosian Quarterly’s Gillian Jakab about bridging culture and activism, the stakes and goals of the campaign, and the artworks featured in the exhibition.

Sébastien Delot is director of conservation and collections at the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the organizer of the first retrospective to focus on Anselm Kiefer’s use of photography, which was held at Lille Métropole Musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut (Musée LaM) in Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France. He recently sat down with Gagosian director of photography Joshua Chuang to discuss the exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Punctum at Gagosian, New York. Their conversation touched on Kiefer’s exploration of photography’s materials, processes, and expressive potentials, and on the alchemy of his art.

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

In 2023, the collector and patron of the arts Gemma De Angelis Testa donated over 100 artworks from her collection to the Ca’ Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna in Venice. On the heels of that exhibition, she met with Gagosian senior director Pepi Marchetti Franchi to discuss the genesis of her collection, the key role of her organization ACACIA (Friends of Italian contemporary art association) in enriching the world of contemporary Italian art, and what it means to share one’s collection with the public.