Nina Simone, Our National Treasure

Text by Salamishah Tillet.

November 9, 2016

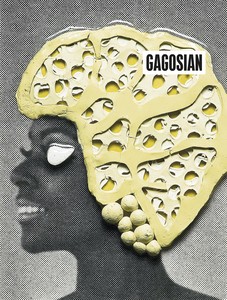

Philip Hoare, author of The Whale and The Sea Inside, creates a narrative about Ellen Gallagher’s newest lithograph, Lips Sink.

Ellen Gallagher, Lips Sink, 2016, lithograph, unframed: 20 × 23 ⅝ inches (50.6 × 59.2 cm), edition of 20 © Ellen Gallagher

Ellen Gallagher, Lips Sink, 2016, lithograph, unframed: 20 × 23 ⅝ inches (50.6 × 59.2 cm), edition of 20 © Ellen Gallagher

I don’t want to do this. But I have to. Clinging to my lover’s coffin. After the apocalypse. I'm borne up on the vortex, the final aftermath. The sea is brown and it is looking at me. I’m another orphan, waiting to be saved. I’m the only one left to tell the story. Only me, and thee, dear watcher.

The sky is brown and the ocean is deep. Full of slimy things. The sea fowl circle around me. They’d take out my eyes if they could. Christ knows where I am. God has forsaken me.

He carved this for himself; he was already lost, he knew what. We shared a bed.

In Turner’s less monstrous pictures of whales, the black shape lurches up from the waves like some blunt missile about to be launched, or some terrible thing being born. The blood spurts from him like his spermaceti. The harpoon’s line is an umbilical. This is the same water into which Africans were thrown overboard. Insurance was collected. They were not. They too were orphans of the ocean. Or reborn. Their bones have turned to coral by now, and their eyes to pearls.

Across the sea from where I write, Ellen Gallagher looks out over the dock at Rotterdam. Like this place, it is an industrial port. It is connected to Red Hook, the one for the other. They are both home to her. She is connected by the ocean in between, only tentatively tethered to the land like the moored ships outside. Her pictures rise up and down in her warehouse, from floor to floor, like flensed whales ready to be tried out. Everything is a try-out. The brown waters outside have carried immoral trade on immemorial seas. Stolen people, stolen animals. The eyes, your eyes. Bundled up out of the ocean. Christ, what have we done?

At the end of Moby-Dick, the sea rolls on, as it had done for five thousand years. Known time. Extinction. The heresy of Melville’s book projected an impossible past in which other creatures had lived; and looked forward to a time when the world would be flooded anew, and the whale would spout his frothed defiance to the skies. When a whale dives, it leaves only a clear calm circular pool, the very obverse of the whirling vortex into which the Pequod sinks. The Inuit believed that that pool was a mirror into which the whale could look, into our world; and we could look into its own, through what Melville called the ocean’s skin. But here the skin has erupted, spewing out Ishmael, the only survivor of the tale.

And he alone lived to tell thee.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Whalers, c. 1845, oil on canvas, 36 ⅛ × 48 ¼ inches (91.8 × 122.6 cm)

Whaleships were the oil tankers of their day, microcosms of the new world, a world of depredation and dominion, the inaugural acts of the Anthropocene. Their crews were New Englanders, Cape Verdans, African Americans, Native Americans, Polynesians; heathens, Christians, savages, fugitives—the traces of what America was to become, pursuing the animals whose protean oil would lubricate and light the industrial revolution, and its new forms of slavery. Out there these men felt free. It was the worst job at sea, but they had no alternative. Melville and Turner saw the poetry in their despair, and in that of their prey. The one for the other. Another exchange. The brutality visited upon them would be visited in turn. Oh the world, ah the whale.

When Ishmael embarks on his mad voyage, he walks into a New Bedford inn, a womb-like, ancient interior, hung with “horrifying implements,” the tools of the tradesmen who frequent the place. There he is confronted by an image he cannot discern or make sense of: a tobacco-stained, “boggy, soggy, squiggy picture” that only gradually resolves itself in a ship on whose masts are impaled “an exasperated whale.”

Inspired by Turner’s whaling scenes—brought together for the first time this year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York—the Spouter Inn picture is a foment of something primeval, perhaps evil; a prophesy, an augury, like the albatross slung around the Ancient Mariner’s neck, like the sea fowl which will circle in the last scene. It is as if Ishmael’s fate is embedded in that picture, as if his future were animated in its numinous, elusive mass of nothingness.

That night he is told of a “dark-complexioned” harpooneer with whom he is to sleep, there being no other room at the inn. The man is Queequeg, the first person of color to become a character in his own right in a work of fiction. By the morning the two men pronounce themselves married; they are bound to each other for the duration of their voyage on the Pequod.

Only gradually do we realize the fate that awaits them; channeled through the medium of Queequeg’s dreams. Filled with his own premonitions of their insane, lightning-struck captain’s intent on revenge on the great white whale, an animal more metaphysical than real, immortal and ubiquitous, able to be present in two places at the same time, Queequeg falls ill and, determined to die, orders the ship’s carpenter to make him a coffin; only to suddenly rally and recover.

Yawning and stretching, the islander jumps up out of his death-bed and “with a wild whimsiness,” proceeds to use his coffin for a sea-chest, “carving the lid in all manner of grotesque figures.” Later, in another omen, one of the crew drowns when he falls from the mast, the ship’s carpenter is ordered to replace the life buoy lost in the failed attempt to save the man. Instead, Queequeg hints “by strange signs and innuendoes” at his coffin.

“A life-buoy of a coffin!”cries Starbuck, determined to restrain these mad men.

The lid is nailed down and the seams caulked, much to the carpenters’s dislike.

“Cruppered with a coffin! Sailing about with a grave-yard tray!”

“Ye but strike a thing without a lid; and no coffin and no hearse can be mine —and hemp only can kill me! Ha! ha!”

As the carpenter is caulking the coffin-life-buoy, Ahab, accompanied by his familiar, the black cabin boy, Pip (who has lost his mind after his own immersion in the ocean), talks to himself in a mad, existential Lear-like aside, as he listens to the tapping of the mallet.

“So man’s seconds tick! Oh! how immaterial are all materials! What things real are there, but imponderable thoughts? Here now’s the very dreaded symbol of grim death, by a mere hap, made the expressive sign of the help and hope of most endangered life… Can it be that in some spiritual sense the coffin is, after all, but an immortality-preserver!”

If Moby-Dick is a legendary text, and its great white whale a modern myth, then this is a solemn, signed sequence in Melville’s book, one which thrillingly, terrifying announces the appalling climax of the story. The beginning of the end, initiated by the fate of the falling sailor, his life failed by the lack of a life-buoy; now the new, deathly life-buoy augurs the fate of all the rest.

In the last manic and fatal hunt for Moby Dick, the demonic Ahab defies the waves.

“Ye but strike a thing without a lid; and no coffin and no hearse can be mine—and hemp only can kill me! Ha! ha!”

In the mayhem, pulled out of his whaleboat and into the sea, Ahab is bound to the whale by rope; and is dragged down, uncoffined, into the depths. The ship sinks, stove by the whale, and it is the unwitting coffin-life buoy that saves Ishmael, the carved box which bears him up and out of the tale. The one for the other.

Where the doomed sailor fell like Icarus, from the air and into the sea, Ishmael rises up, born again out of the amniotic ocean, while down below, the grand hooded phantom of the whale swims on, ever and ever deeper, into the darkness below.

In Ellen Gallagher’s picture, itself created out of findings and leavings, even of human hair, we see the pity and beauty; the swirling storm-vortex and the center of the calm at the center of it all, your eyes, looking on, while all around is wildness and despair, sublimity and the infinite sea. The one for the other.

Text by Salamishah Tillet.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

The Summer 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Afrylic by Ellen Gallagher on its cover.

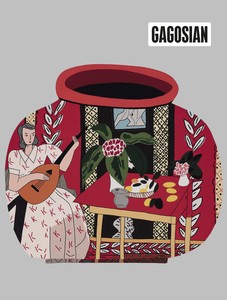

The Spring 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Red Pot with Lute Player #2 by Jonas Wood on its cover.

Ellen Gallagher in conversation with Adrienne Edwards.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.

Louise Gray on the life and work of Éliane Radigue, pioneering electronic musician, composer, and initiator of the monumental OCCAM series.

Tracing the history of white noise, from the 1970s to the present day, from the synthesized origins of Chicago house to the AI-powered software of the future.

Ariana Reines caught a plane to Barcelona earlier this year to see A Sea of Music 1492–1880, a concert conducted by the Spanish viola da gambist Jordi Savall. Here, she meditates on the power of this musical pilgrimage and the humanity of Savall’s work in the dissemination of early music.

Dan Fox travels into the crypts of his mind, tracking his experiences with goth music in an attempt to understand the genre’s enduring cultural influence and resonance.

Charlie Fox takes a whirlwind trip through the Jim Shaw universe, traveling along the letters of the alphabet.