Adrienne Edwards is a Curator at Performa, New York, Curator at Large at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, and also a PhD candidate in performance studies at New York University. Her scholarly and curatorial work focuses on artists of the African Diaspora and the Global South. She is a contributor to numerous exhibition catalogues and art publications, including Aperture, Art in America, Artforum.com, Parkett, and Spike Art Quarterly. Photo: Lorna Simpson

Ellen Gallagher was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1965. She lives and works in New York and Rotterdam. Gallagher has recently been the subject of survey shows at the New Museum, New York, Tate, London, and Haus der Kunst, Munich. Photo: Philippe Vogelenzang/Trunk Archive

Adrienne EdwardsSo we begin with a sailboat.

Ellen GallagherYes, I thought this might be a good place to begin. It was a long time ago. In 1986, I wanted some adventure, so thought I would do something called SEA Semester out of Woods Hole, Massachusetts. A group of students study celestial navigation and oceanography in Woods Hole at the SEA Education Association, which is adjacent to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Then for the second part of the semester you work on your own independent research project. Of course I waited until the last minute to choose mine. I went to the Oceanographic Institute and a scientist showed an incredible slide show of pterapods, these wing-footed snails. I thought they were the most beautiful things and so, not really paying attention, I jumped into that—that would be my project. Turns out they were practically microscopic [laughter] and it meant I was on board a sailboat doing four-to-five-hour Neuston-net tows, collecting these things, then looking at them under a microscope and trying to make drawings. These were actually the drawings I used to apply to art school. But the other thing about this was the voyage itself. We began our journey in the Caribbean and we moved by Saba and Bonaire up to Martinique. And Martinique was for me, I guess, a life-changing experience. When we arrived it was just before Christmas. We’d been sailing for I think a good month at least, about twenty-six of us on board that sailboat. We arrived in the port of Fort-de-France and you could walk through the port, through this neighborhood, and end up right in the center of Fort-de-France, and there was the Schœlcher library, the library of Victor Schœlcher, an abolitionist from France. Schœlcher was incredible—he combined activism and letters and it’s his archive that began this library. He was a radical voice against slavery, and against the French government’s violent taxation of Haiti as reparations following the country’s independence. The building was built in Paris, it was part of the World Expo of 1889, and then it was cut up and reconstructed brick by brick in Fort-de-France.

So the idea of this library had a kind of radical potential for me. I was just back there for the first time since 1986. Aimé Césaire’s office is around the corner from the library and you can visit it—it’s a bit like the Freud Museum in London, Freud’s former house, which is open to the public as well. Anyway, when I visited Martinique in 1986 there were student protests going on, and I wanted to join in because it sort of seemed like a party to me, but they explained that they were fighting for the right to take the baccalauréat, to have access to France. They wanted to attend university, to not be trapped in this drop-off point in the Caribbean. So as a New England person through and through, this felt to me like my first time as an adult in Europe and also my first time in Africa. I’m speaking subjectively—that’s what it felt like to me.

AEBecause Martinique represented a coalescence of these two cultures in a way? Which is what makes it so interesting, right? We’ll get to something about this kind of liminality that you’re really interested in, but formally, when you think about the dismantling and reconstruction of this building, brick and by brick, something starts there that enters your work. Literature has a recurring presence in your work as well.

EGYes.

AEAnd this was also the moment, I think, when you began to think about the imagery and mythology around water. So all of these things begin to create a cypher.

EGAnother thing in my mind when I went sailing, I remember, was that Langston Hughes had joined the Merchant Marine. I actually looked into the Merchant Marine before I went to SEA Semester and my mom was like, I think that’s a bit too rough for you [laughter]. So, yes, Langston Hughes. And I remember being at sea and just being struck by its geographies; and the collecting of the pterapods, which was such a detailed ritual for me and almost a gridded ritual, like every day at a certain point, collecting again. We were also collecting temperature readings, and the temperature readings alongside the collecting of the pterapods—my idea for the pterapods was, they’re semimobile, they get stuck in the currents and eddies, and I was going to come up with a map of the Caribbean somehow by mapping where the pterapods were. And that didn’t really work [laughter]. But what I did discover was that there were other bodies of water within the Caribbean that made it up, it’s not just one singular body of water. I started finding these temperature spikes during my Neuston-net tows and I discovered that there was another body of warmer water just below us that was salinity-maximum water. That was really shocking when we were on board, that the ocean actually isn’t this whole being, or it’s a whole being made up of multiple diverse bodies.

AEWould you tell us a bit about eXelento?

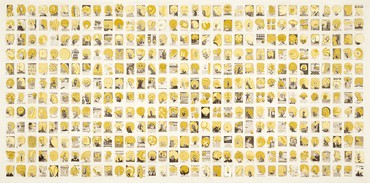

EGYes, eXelento is made up of 396 pages. I started by unbinding magazines from the 1940s or so and kept going until 1978.

AEWhat kinds of magazines?

EGEbony, Our World, Sepia—mid-century race magazines. So I unbound and then scanned them. This intervention of the scanner created a sense of infinite space for me. I scanned each page and then I chose what I was going to reformat—fragment, collage, tweak. It’s not a stable archive in that sense.

AEI saw eXelento for the first time at The Broad recently and for me it was, I mean, [sings note] amazing to see this in person. If you haven’t seen it yet, you must see it, and you must see it during the day, with natural light. It is jaw dropping. And I understood this kind of intervention in a different way, because eXelento is what year?

EG2004.

AE2004. So here you have the grid, which becomes so important in your work. Even when you can’t see it, it’s there. And the way you approach the grid has these beautiful references to Conceptualism, in particular through the notion of seriality that you see here, but it also has a direct relationship to abstraction. And your intervention with the printed matter and with the Plasticine gives it a completely different, not just texture but life, it imbues it with something radically different. So I’m interested in how you intervene in these kinds of styles of modernism by inserting things like printed matter, and your choices of certain printed matter. And how something like the Plasticine is entirely disruptive—it’s a bit naughty [laughs].

EGYes, but in some ways I think of the Plasticine as a binder as well. For me, the idea that the pages were already in circulation was important. I was jumping into something that was preinseminated, that had already been in the world, and I was somehow sufflating it, breathing life into it, no matter how subjective or idiosyncratic, making it live again in my realm. The fact that it was circulating also meant that the process wasn’t just this one-to-one reading of signs, which was starting to feel constricting in earlier works. This living matter that was already in circulation somehow, but had been passed out of circulation and cast off—to bring that back into circulation seemed to me a way to move backward and forward at the same time. It gave me the potential to project my stories forward in time but also backward in time.

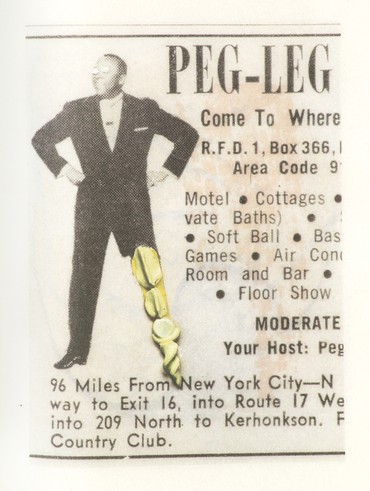

And the Plasticine, like the pages themselves, is this other ephemeral matter. I guess you’re not supposed to touch it—I’ve been told not to encourage you to touch it [laughter]—but it is never going to dry completely. And the pages are laid out in a grid, so there’s a kind of weave or story that’s built from these 396 pages and then the Plasticine is worked top to bottom, left to right. And there are reoccurring characters throughout the series—the nurse, the peg leg.

The paper is fragile, so it’s scanned onto archival newsprint and then I begin the Plasticine, top to bottom, left to right, because I have to sit on the clean part of the painting to work on it. As I always do at some point in my work, I work on it on the ground—I’m on top of it, hovering over it, building it, really constructing it. What makes it go fluid for me is that even though these paintings are labor intensive, maybe eight pages a day get added and they’re improvised one by one. The story may relate to puns in the text, for instance, or it may relate to puns in the forms, so the Plasticine is a kind of binder—but also a kind of lens that lets you see the layering, with stories beneath it and another layer on top of it. So it’s not so much the grid of modernity that’s mapping the painting, it’s a register in motion. I hope.

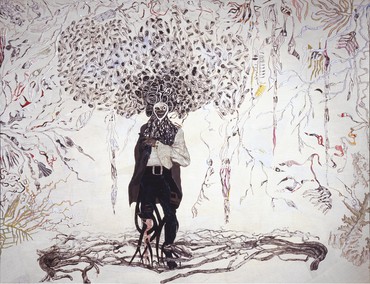

AE Let’s discuss Bird in Hand [2006], which for me is a great example of how you complicate the distinctions around figuration and abstraction. In fact it relates to all of those things, it’s a swirl of those approaches, yet it’s also emblematic of your acute sensibility toward the liminal, toward the in-betweenness of things. Can you talk about how how you approached that, particularly with this work?

EGThis was really about accumulating layers of printed matter. There’s a penmanship paper that’s built like a kind of Mercator map, so it’s twisted. And the central figure really began as an accumulation of matter, so there’s always this falling apart and coming together. It’s quite three-dimensional in person and there’s salt, literally, Nepali salt encrusted in an oil paint in the vines combing through the figure’s neck. So there are all these bits that really fall apart into just matter and then come together from a distance as a figure.

AE How did you come to penmanship paper? What was that moment of, Wow, I can work with this?

EGWhile I was in art school in Boston in the late 1980s there was a poetry collective of young African-American poets like Sharan Strange. Ntozake Shange was the first reader, Samuel DeLany came and read—it was an incredible time. So as a young art student I got to go to this Victorian house in Cambridge and see and experience these readings and this idea of audience, and I was so frustrated, I was really jealous of the poets, because there was a way in which what they were doing was both abstract and really lucid. I was envious of that, and thinking about that, and then I was in my father’s neighborhood in Providence, Rhode Island. I was walking through this neighborhood, which had been somewhat decimated by highway construction, and what had once been a playground with a swimming pool, where my cousin had been the lifeguard and I had learned to swim, was now emptied out. This was during Ronald Reagan’s era and he emptied out a lot of city pools, so they became less vibrant than they’d been as I’d remembered them in the 1970s growing up. Anyway, I found a piece of paper that had been perfectly folded up and it said, “We are a drug-free school. Have a nice day” [laughter]. It was penmanship paper, with a smiley face, and that just seemed so poignant to me. I took it back to my studio and kept it. Then I think I bought some sheets, glued them to canvas, and they seemed really fleshlike to me. And I liked that they were ephemeral, that they yellowed. I was always inscribing the paper with my pencil and it would crinkle or react, and you could always see the weave of the canvas beneath it. So there was this vulnerable material quality.

“Watery Ecstatic” was really about accumulating layers of printed matter. There’s a penmanship paper that’s built like a kind of Mercator map, so it’s twisted. And the central figure really began as an accumulation of matter, so there’s always this falling apart and coming together.

Ellen Gallagher

AEWatery Ecstatic, an ongoing series that you started in 2001, is compelling to me because it somehow operates within the visual language of abstraction yet combines it with the aquatic world. But for me it’s so slippery what you do with these drawings because they somehow address the unspeakable of the transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage, in particular in relation to water and the ocean and all that is bound up in the Atlantic. And perhaps to me that abstraction is uniquely situated to somehow hold these stories, not address but hold them and the myths that come out of them. I’m interested in how you repeatedly return to this series—it seems almost as though you’re trying to exhaust it somehow, but it’s a sinkhole, it needs a bit of an escape, the stories need to be able to be fugitive. The works are profoundly labor intensive. There’s so much there, I was literally hovering. It’s incredible how you make these works, where you can see your hand in such an intense way. Would you talk about how you came to these works and how you make them?

EGWell, they’re built. They’re made on thick watercolor stock, and I’m drawing with a pencil first and also a scalpel.

AEYou’re drawing with a scalpel, I just want to note that [laughter].

EGSomehow I became more confident drawing with a scalpel. I mean, with pencils you can make a mistake but with a cut you just have to keep going forward, so for some reason it’s more about improvisation. I guess Watery Ecstatic goes back to the SEA Semester, or to being at sea, looking into the sea, the idea of the sea—it’s about mapping. It somehow relates to Bird in Hand even though they don’t look alike. For so long the sea was a liminal space, unknown, we didn’t have access to its depths. It was also a literary space, a speculative space, especially in early maps. But now, as we’re able to go farther into the depths, it’s a combination of natural history and myth. And for me they don’t cancel each other out, they fold in on each other and make each other stronger and more mysterious.

Then there are the jellyfish, a key literary image for Césaire and his thinking about the archipelago. Jellyfish are actually made up of several organisms, some of which are eating it as it moves through the water. And some jellyfish can self-replicate, so there’s this idea of being able to reproduce oneself in isolation.

The printed matter is actually cut and embedded into the watercolor paper.

AEIf you study it closely, it looks like a face that you’ve extracted from printed matter, but then—

EG—painted into and cut into. And then bits of text, e’s and o’s, were embedded like pods or bubbles in the seaweed.

AEE’s and o’s also recur in your work.

EGWhen you think about collecting pterapods to map a vast space, the e’s and o’s are coming from that same place in me. It’s about taking the smallest portal, the least important signifier, and trying to make it your opening into a vast expanse. The e’s and o’s are those small signifiers but they’re also vowels, they’re something that can expand.

AEDew Breaker, which you made for the Venice Biennale in 2015, feels related for me to the Watery Ecstatic series. How did these paintings come to be, and what were you thinking about in terms of going from drawings to very large-scale paintings with these ideas?

EGLike a lot of my work, it started as an accident. I built something up, erased it, sanded it down, and then was getting this almost quilted, bulbous use of the penmanship paper—instead of twisting it or mapping it, it was more built up like a kind of bandage. And I was thinking about Filip De Boeck and his film on the Congo, about how funerals there were being disrupted and elders attacked out of a strong feeling of disappointment and rage. And then thinking about Edouard Glissant, and the idea, which I think extends Césaire’s thinking, of these sentient geographies. So I started to think of vertebrae stacked together, made up only of the penmanship paper or the printed matter. And The Dew Breaker is an Edwidge Danticat story, she’s talking about Papa Doc Duvalier’s violent controlling forces—

AEIn Haiti—

EGAnd their name for the time of day when they would come and do their work. So I was linking these stories together and I wanted to bring the Ebony pages into these stories as well, and the penmanship paper, and the matter itself would build the figuration and be a kind of bandage, not falling apart and coming together in the same way as Bird in Hand but more like a bulbous bandage. So the painting itself was kind of corpselike.

AEIn 1997 you began to make black paintings. I’d love you to talk about why.

EGWell, my father passed away in 1997 and it wasn’t so much that I was close to him, but suddenly I felt as though I somehow I had less protection in the universe. And it surprised me that I would feel that way. Yet the death of a parent, even a parent who wasn’t in my day-to-day life, made me feel that somehow my stars were permanently going to be less aligned in some way.

The symbolic for me is about carrying and the potential to carry—it’s like magic.

Ellen Gallagher

AEThe first time we spoke about it, you said you felt unmoored, which is kind of equivalent to the visual experience of looking at these paintings. You get this sense of a void, not a negative thing but more about an incredible tension between this sheer blackness and the metallic resonance of the painting. The way the sienna ground comes through, in the most subtle of ways, is to me so reminiscent of the basic elements of our universe—when we think about black holes and what black holes do and how they seem dense and impenetrable, yet it’s nothing but openness. These paintings are very generous in that way for me.

EGThank you for saying that. In Bird in Hand and eXelento, which both came after this, I talk about the grid as a kind of register that signs can move across. Maybe these black paintings were the first time, or the most successful example, where I thought, “I get it. I can do this. Wow, it happened. It’s not just something I want the painting to do, it just did it, it made itself.” And building these works was really labor intensive, it was gluing pieces down bit by bit, which is the opposite of painting, in a sense—there’s no fluidity. But then when the enamel skin is laid down, it covers the penmanship paper and the rubber below, and it also throws them into bas-relief. So there’s this centrifugal aspect to the grid, which later becomes the register that the characters can move across, that can allow the signs to reach out to the world.

AEWhen you talk about characters, is that different from symbols?

EGNot necessarily. The symbolic for me is about carrying and the potential to carry—it’s like magic. So a character like a jellyfish can be made up of several different bodies, can exist in different times, can be a character that’s symbolic.

AEPerhaps you can talk about Kapsalon, particularly in the context of working in Rotterdam.

EGKapsalon means barbershop, hair salon, in Dutch.

AEAnd you did these for the 2015 Istanbul Biennial.

EGYes, but I’d thought about them earlier. I thought about them as a way of making Dutch black paintings or Dutch national paintings. They’re made with thicker-gauged rubber, they build out, but they also fall in like a petri dish. And the printed matter is now really sealed, adhered, to the rubber. It’s almost like the printed matter has become Plasticine-like, claylike.

Kapsalon is a dish that was created when a black Cape Verdean hairdresser went to a shawarma shop and basically made an African stew out of a shawarma dish, and then really got a taste for it. It’s essentially shawarma, French fries, lettuce, mayonnaise, sambal sauce, spice, and some salad dressing. And it’s become this Dutch national dish. I like the idea of all these ingredients gone watery again in a tin takeout container. And I was thinking of this time of stricture, where we are so disconnected, but these black men in Rotterdam had a flow and created this thing, and it was also about accepting somebody coming into your stuff and making their thing out of your thing and turning it into something that is now—I think it is the Dutch national dish [laughter]. It’s huge.

Rotterdam was heavily bombed during World War II, it was decimated. So our city center is really black, unlike the city centers of Amsterdam or London or Paris. Rotterdam is a working class port town where the center looks more like Queens than like a European city. There’s always construction, so there’s always this sense of rebuilding and making, and great architecture and design come out of Rotterdam, it’s about starting over. And there’s also this very salty vernacular that comes out of Rotterdam because it’s a sailor town, it’s a port town. So the big grand central station was named Station Kapsalon [laughter] and you can’t stop this, that is really the name of that station [laughter]. I find this incredibly beautiful, this 3D vernacular that is living matter. The mayor of Rotterdam was born in Morocco, and he went back to Morocco for a holiday, and a Dutch reporter asked, What do you miss from the Netherlands? And he said kapsalon [laughter]. I just thought that was the most beautiful thing. Maybe I’m being sappy or poetic but I thought, You know what, he’s missing that flow. To me, that’s black abstraction. He’s missing that flow and I just thought that was incredibly moving.

Artwork © Ellen Gallagher. This conversation was excerpted from a longer conversation that took place on February 24, 2017 as part of The Broad’s partnership with USC’s Roski School of Art and Design.