John Elderfield is chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was formerly the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He joined Gagosian in 2012 as a senior curator for special exhibitions.

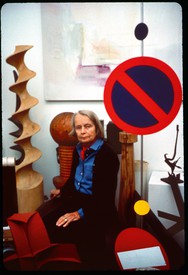

Lauren Mahony is a director in the publications department at Gagosian, where she has worked on exhibitions and publications devoted to Willem de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Brice Marden, and David Reed, among artists, since 2012. She previously worked as a curatorial assistant in the department of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Rob McKeever

Lauren MahonyHelen Frankenthaler began making a name for herself in the New York art world in the early 1950s and is typically considered a second-generation Abstract Expressionist. Following her invention of the breakthrough soak-stain technique in 1952, why do you think she revisited Abstract Expressionism in the late 1950s, having moved in a different direction?

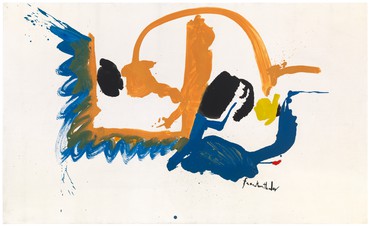

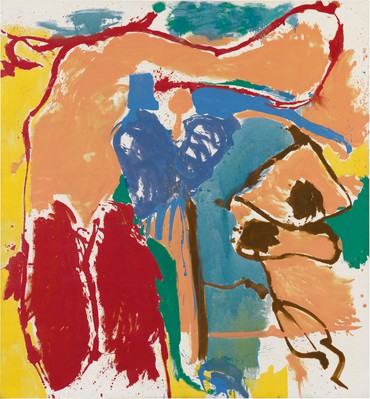

John ElderfieldWell, there are really several periods in Helen’s work within the 1950s. There’s the first soak-stain period, from Mountains and Sea, in 1952, to late ’54. Then, while the soak-stain technique isn’t abandoned, it becomes more material, more Ab-Ex in feeling. In 1956, Helen moves back to something closer to the earlier soak-stain technique—only to again move closer to Abstract Expressionism in 1959–61. In the early 1960s there’s yet another change, where she moves into a thinner kind of painting and more emphasis on color. So about every three years she’s doing something different. That makes the change in the late 1950s less surprising than it may seem at first.

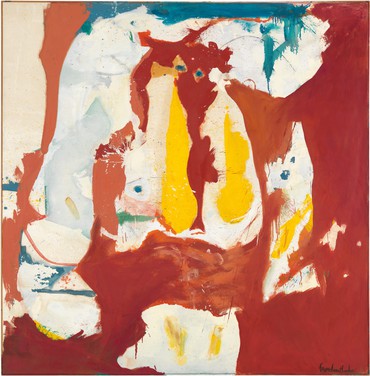

LMInterestingly, the period that this show covers, from ’59 to ’62, falls precisely between the first two Frankenthaler shows that you’ve organized for Gagosian. The first show—the Painted on 21st Street show—ran from 1950 to ’59 and examined all of those changes that you just described in the 1950s. Then the next show, Composing with Color, covered 1962 and ’63 and dealt with her transition to acrylic paint, and to flooding the canvas with color, using much more intense hues. The short time period of the present show, of 1959 to ’62, feels different, fresh, and new to Frankenthaler studies in general. These paintings are not well known and they haven’t been exhibited in a long time, if at all—the show in Paris marks the very first exhibition for several works, including First Creatures [1959] and Untitled [1959–60]. How did this show come about? And how did you react to seeing the paintings again after such a long time?

JEWell, after doing the 1950s show, we wanted to provide a better sense of the Frankenthaler people knew, with bright color and so on—the ’60s painting. This Paris exhibition offered us the opportunity to see her development between 1959 and ’62 fleshed out more. The closer we looked at this group of works, the more I realized that there was something very different happening in this period.

LMWhat was happening in her life at that moment that might have influenced this change?

JEWell, there was her 1960 retrospective [at New York’s Jewish Museum]. It’s not surprising to think that an artist’s work might respond to a big survey exhibition. This one covered her work from the early 1950s, before Mountains and Sea, right through to the ’59 pictures. That must have been poignant for her as a very young artist, to have that all laid out. She must have looked back at what she had done and then considered what she would do next. Another motivation for artistic change was probably the change in her personal circumstances: in 1958 she had married Robert Motherwell. Before that, until the mid-1950s, she had been in a romantic relationship with Clement Greenberg, and the experience of looking at art with him in those early years has long been recognized as being very important to her.

LMWhich countries did she and Motherwell visit?

JEFrance, Spain, and Italy.

LMYes, she made many paintings in Italy in 1960, when they were on vacation in Alassio. Also, Hendaye, from ’58, shares its name with a port town very close to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, where they spent most of their honeymoon in ’58. So there are interesting connections to their time in Europe in some of the works you selected for the show. What about the context of New York, though? The show is called After Abstract Expressionism.

JEIn 1959, Helen was doing very Ab-Ex pictures, and that was the year of the famous Willem de Kooning exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery that sold out on the first day—the high point of 1950s Abstract Expressionism’s reception up until then. Helen’s work of 1959–62 belongs to that moment. But our exhibition ends in ’62, when something else begins in New York with the New Realists exhibition.

LMThe groundbreaking Pop art show, also at the Sidney Janis Gallery.

JEYes. That show marked an absolute change in the New York art world. And there was also a change in Helen’s work at the beginning of the 1960s, moving it toward the Color Field painting with which she would become most associated. It’s very interesting to me how the 1959–61 works in our show—coming between her celebrated soak-stain work of the 1950s and her Color Field paintings of the 1960s—have somehow slipped out of her history. Most people must have jumped over them. And to some extent, Helen did herself, in subsequently telling her own history.

LMThese late-’50s-to-early-’60s paintings are more aggressive than what came before or after. Can you talk a little bit about where the title of your essay comes from, that phrase “Think Tough, Paint Tough”? And I feel like the addition of “Move On” to the end of your title attributes to Helen a confidence about her approach to painting—the idea that she would try something and move on to the next thing, rather than dwell on it.

JEThe title comes from the critic James Schuyler, who wrote in a review of her 1960 retrospective that “part of Miss Frankenthaler’s special courage was in going against the think-tough and paint-tough grain of New York School abstract painting.” That’s true of the 1950s work, by and large; she didn’t really fit into Abstract Expressionism, being celebrated for painting soft-looking pictures. The implication of that response, though, was that she wasn’t a tough painter, yet as Helen knew very well, the analogy between being a tough artist and making works that look tough is obviously a misleading one, although it’s easy to fall into. Clearly Helen wouldn’t have become the artist she was if she hadn’t had a personal toughness and drive—she was someone who very much wanted her own way, was strong about what she did and believed in what she did. But in the 1959–60 period she not only thought tough but also painted visibly tough-looking paintings in a way that, as Schuyler said, she hadn’t done earlier. And she would do so later again, for example in the late 1970s.

LMAnd early 1980s.

Clearly Helen wouldn’t have become the artist she was if she hadn’t had a personal toughness and drive—she was someone who very much wanted her own way, was strong about what she did and believed in what she did.

John Elderfield

JEYes. It’s worth remembering here that the early criticism that Helen wasn’t a tough-enough artist was associated with the idea that her work looked “feminine.” Words like “cosmetic” were applied to the color of her paintings. Of course there’s a long tradition of color being gendered in this way, described in Jacqueline Lichtenstein’s wonderful book The Eloquence of Color. And what people had trouble with in the soak-stain paintings of the 1950s was not only color, but color along with softness. That separates her from, say, Joan Mitchell, who was always perceived to be making tougher paintings because her surfaces were more impastoed.

LMMitchell was more a follower of de Kooning than Helen was, at least at this point.

JEYes—and that certainly contributed to Mitchell being thought a tough painter, toughness being linked to “masculine” paintings.

LMDo you think, then, that some of these tougher paintings of Helen’s were maybe a response to her work being interpreted as too “feminine” or “lyrical”?

JEWell, you know, maybe she wondered if she could paint tough.

LMAnd wanted to prove that she could?

JEYes.

LMThere’s a quote from her from the late 1950s about a painting called L’Amour Toujours L’Amour, from ’57, where she says, “If you think this is too lyrical or too whimsical, you’re not seeing it.”

JEThat’s perfectly to the point. She’s insisting, “Just because you think it looks sweet doesn’t make it a lesser painting.” With artists who become well-known, people inherently desire to have more admiration for the works they feel are more typical of that artist—the works in recognizable signature style. Once at the Museum of Modern Art I was proposing the acquisition of a very geometric drawing by Matisse, and someone on the Drawings Committee, which had to approve the acquisition, said, “This isn’t what a Matisse drawing should look like.” So I can imagine people saying of First Creatures, for example, which comes across as a very aggressive work, “This isn’t what a Helen Frankenthaler painting should look like.” But if you take that approach, you’re not really seeing the artist’s full identity.

It’s actually been terrific to work on this brief, focused period. It’s allowed us to think about the change that was happening in her work.

LMAnd to look at these works in depth, and in the context of everything that came before and after.

JEAnd the works are pretty extraordinary, some of them very unexpected. Many people don’t have a strong sense of the course of her development, or haven’t studied her transitions at this level of detail. I think even scholars who know her work will find these lesser-known periods revelatory and exciting. Of course, once the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation has published its catalogue raisonné, it will be great to have a real sense of what was happening work after work for her entire career.

One interesting thing that starts to happen in the second half of the 1950s, for example, is that the canvases become more depictive than they were in the first stain period. That depictive quality is obviously there in the light, thin lines of Mountains and Sea, but it soon disappears from subsequent paintings, then comes back with a vengeance in ’56 and ’57: the paint is very much poured on and manipulated but there’s a clear figurative emphasis. At times you’re not quite sure what the figure represents, but when you think of Europa [1957]—

LMor Venus and the Mirror [1956]—

JEYes, in both of those works the figuration is produced through an expanded version of linear drawing, which is poured on as well as drawn with the brush. And the figuration can be as much in negative spaces as in positive ones. It’s fascinating to see this evolve in the period of this exhibition. Just look at First Creatures and ask to what extent you can see creatures.

LMI see them, and I’m kind of fascinated by that, because it reminds me of Helen’s description of seeing Jackson Pollock’s black painting Number 14 (now in the collection of the Tate) at Betty Parsons: she saw a fox in it, and it reminded her of children’s-magazine illustrations where you have to find the hidden figure.

JEThen of course there’s the fox in—

LMWinter Hunt [1958].

JEYes, a little menagerie of animals appears at this point.

LMFirst Creatures is early in showing what may be a swan. That’s a figure she developed later on, in the early 1960s, when she created one of her few paintings series, the Swan Lake series.

JEWhen you talk to artists about their work, you will later always wish you had asked them about certain things that you never did. Like, where did those swans come from?

LMShe talked about this a little to E. A. Carmean [in Carmean’s exhibition catalogue Frankenthaler: A Paintings Retrospective, 1989]. He asked her about individual paintings, including Swan Lake I, and she basically said that in working on the painting she wasn’t intending to come up with these swans or creatures or any kind of figuration, but that it appeared, and she was ready for it, so she developed it from there.

JENot much has been written about this, and it’s interesting. There are a lot of animals in early modernism, particularly in Surrealism. There are birds in Matisse, and early on, in 1916, there’s a dog. And there are of course animals in Picasso, and in Braque’s studio pictures of course.

LMAnd as you’ve said in your essay, Helen saw every show, whether it was with Greenberg or later with Motherwell. Even as a student she was very savvy about what was going on in New York. Miró was a big influence on her early on.

JEI hope that as the catalogue raisonné develops, the Foundation can include a compendium of shows she could have seen, based on when she was traveling or in New York. It would be a great resource for scholars.

LMYes, and she would often refer to paintings she had seen in her letters and postcards.

JEShe often responds to things and you think, “Why does she like these?” Then you look at the work she was doing at the same time: sometimes she’s liking a quality similar to something in work she’s already done; at other times what she’s seeing relates to a way she wants to move forward. Once that reading has happened, it opens up that source for her. She may be using these sources consciously or they may have just lodged in her memory and then unconsciously come out when she was painting. At some point it would be great to have a study of the iconography of her work.

LMWhat was it like looking at the paintings with Helen when you were working on your Frankenthaler monograph [1989]? Did she seem nostalgic about the 1950s, or any other particular period, or was she able to look at the works objectively?

JEA bit of both. In some cases she was looking at paintings that she hadn’t seen for a long time, because they’d been in storage. There were some that had once been stretched but had been taken off the stretchers and rolled, to make storage easier. She was very interested to see those again, because she hadn’t looked at them for a long time. There were others that had never been stretched, and that she saw differently after so many years: at the time, maybe she’d thought the painting hadn’t worked, but looking back she realized there was something there. So she might decide to stretch it, and one of the studio assistants would get out tape and mark out what it should be. She’d kept quite a lot of 1950s paintings, she must have recognized that there was something special about what had happened then. Some had been sold early on, but there were still a lot that hadn’t been, and her market was sufficient that she didn’t need to sell them. She often felt strongly about certain things, so she wasn’t going to part with them unless she knew that somebody cared enormously about them. Anyway, it was a really great process.

LMHow did you decide which works to include in that book?

JEWe would meet for hours. We never seemed to have enough time. We eventually got to the point of putting photographs of works on the walls, and all the studio walls were full of them. When we had to decide what would go into the book, we went through them together and she would say, “Oh, I have to have that.” And I would say, “You know, we’re actually including too many from this period.” And she would say, “Well, we’ll figure it out when we get to that point later on.” I went through the same thing with Richard Diebenkorn—it was really hard to get him to eliminate works from a book or exhibition because the implication was that he thought less of them. It was the same with Helen, she got so attached to certain works they just had to be there. Others she would gracefully surrender as the process continued. It’s worth saying here that publications and exhibitions done in artists’ lifetimes are bound to be different from posthumous ones. Some curators and authors chafe against the will of their subjects, but I actually think it’s good for the historical record to understand which works the artist esteems and wants in these exhibitions, because opinions will often change later on.

LMHelen was sensitive to Mountains and Sea being so much a focus of attention—she wouldn’t allow it to be in certain exhibitions. Even now, most people focus on Mountains and Sea as her iconic influential work.

JEYes, and of course that has to do with the way in which the history of art is told: through moments of innovation, or a sequence of innovations, one after the next. That implies that artists are most interesting at those moments, rather than later on. And then apparently we’re not supposed to be interested in them anymore because we’re interested in somebody else.

LMYes, and with someone like Helen or de Kooning, who also had a very long career, there’s so much value in exploring those other periods. I agree on how nice it’s been to explore in depth not just what she’s most famous for but these other bodies of work, lesser known even to us.

JEThe notion of a tightly controlled history has fewer supporters than it used to have. There’s suddenly far more interest in how modern painting has developed in different versions and different forms. And it’s great that we’re able to show different versions of Helen Frankenthaler, an artist who was working in different ways but always remained the same person.

LMI agree.

JECézanne’s 1895 show at the Vollard gallery in Paris was really the first time anybody had seen his work in depth, because most of it hadn’t been exhibited before. The response was, “All these different things?” And Cézanne replied, “Yes, everything is different, but everything is a Cézanne.”

Artwork © 2017 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photos by Rob McKeever unless otherwise noted