Angela Brown is a writer and editor from Yonkers, New York. She is currently a PhD student in modern art history at Princeton University.

Angela BrownInstead of starting with the mechanics of this project, which are quite intricate, I want to start by discussing chairs in general. I know that in your previous work, you’ve dealt with gestures related to interfaces, such as iPhone touch screens. We tend to see these devices as extensions of our bodies. What do you think is the difference between complex devices (smartphones or robots) and more mundane objects, like chairs?

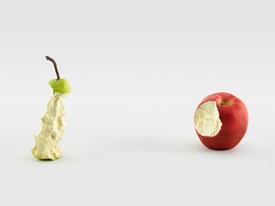

Madeline HollanderOne of the reasons why interfaces are so interesting is that they’re actually choreographing the body. Similarly, if I see a chair, I consider what position the body has to take when it sits in the chair. The way I look at all inanimate objects—digital interfaces, doorways, or countertops—is very much about how they affect the body. I’m constantly thinking about how it would be different if a door handle were in a different position or if a cup were bigger than the grip of a hand.

ABCan you expand on the types of micro gestures you’re interested in?

MHI often think about how daily rituals—waking up, brushing your teeth, eating breakfast, checking your phone—create a unique choreography for each individual. The motions become reflexive, like when you walk into a room and slap the wall and know exactly where the light switch is. Then, when you’re in a new place, you might do the same thing, but there’s no light switch there. One of my favorite things to watch is people going down escalators—or stairs, even. They’re on their phones, not paying attention, and they hit the bottom and suddenly the ground is there, but they anticipate another stair and just kind of slap down their foot. I narrow in on those awkward moments when the person gets an instantaneous reality check—and use these moments as choreographic inspiration.

AbAnd that false step causes the whole spinal cord to compress, since the body wasn’t prepared for it. It causes you to think about your bones, really.

MHExactly. And you realize which behaviors are unconscious and which are conscious. It brings up the question of who’s being choreographed: are you choreographing your day, or is a machine or workflow choreographing your day? A lot of my choreography seeks to expose or disrupt those moments that have been incorporated into our everyday gestures. Or I’ll try to show which objects are dictating our actions.

I did a piece earlier this year at the Artist’s Institute in New York [New Max, 2018], where I created a system between the gallery lighting, four air conditioning units, and four dancers. The dancers performed rigorous movement sequences, heating the room with their body heat, and when it reached a certain temperature, the lights would go off, the ACs would blast, and the dancers would then rest until the temperature lowered to a set minimum; at that point the ACs would shut off, the lights would go back on, and the dancers would start in exactly the place where they had left off. For me, this piece was not just about the dancers: the ACs were performing as much as the dancers were; they had equal but opposite functions.

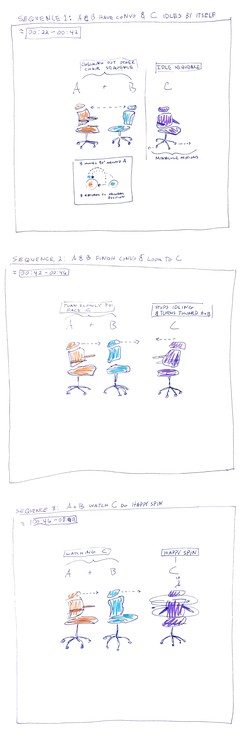

ABHow did you choreograph the chairs in PLAY?

MHThe chairs were already built when I came into the project, so the challenge was to figure out how to make the most of the specific movements that the chairs are capable of. The armrests and headrests don’t move, so all you have are five wheels, the rotation of the base, the angle of the seat, speed, and the rate of acceleration. Using combinations of these five elements, we were able to create really dynamic characters, like unique personalities.

ABPLAY is jarring, I think, because a chair is supposed to be idle, just waiting for you to sit on it. You don’t think about it as something that can react or collect data. Has this project changed the way you think about data collection?

MHThere are two levels to this. There’s the choreography, which develops behaviors that might be read as introverted or extroverted, defensive or flirtatious. But what’s truly exciting is that the real dress rehearsal is going to be when the show opens to the public. To have fifty people interacting with the chairs at once is going to change which behaviors occur. At that point, when we have more data and understand different trajectories and reaction times, we may need to adapt the choreography. In the phase we’re in right now, it feels more like building a landscape; we’re setting the fundamental laws, kind of like gravity. And because the chairs don’t have limbs and facial expressions, I feel like it opens up a whole new level of imagination and projection. There’s always something happening, but whether or not you can map on a narrative depends on your interpretation.

ABViewers tend to try and understand new worlds according to their own worlds.

MHExactly. And that connection point is something that’s really only going to be apparent when the piece is open to the public. I think that’s what makes PLAY very different from my work, actually. Usually, in my work, the choreography has mutated and generated new forms by the end of the exhibition run because every dancer makes it their own, but there’s never been a direct interaction goal, like there is in PLAY.

ABWhen you realize that the art is observing you just as much as you’re observing it, there is a sort of awkwardness there. The viewer isn’t quite sure how they’re supposed to act. But if you think about it, in a gallery there is already surveillance.

MHRight, the security cameras are always there. I think it’s great if there’s that moment when all of a sudden people realize that there are cameras taking data all of the time, that this is no different from anything else. And the chair itself isn’t actually collecting the data, it’s the system as a whole, which is interesting.

ABThey’re not scanning each visitor?

MHNo. The chairs know where you are, but there’s a whole network of cameras that process the data, then that information changes the way they move, enter, exit, etc. Once enough visitors have been observed, the network can start predicting how people are going to move. It’s less about the individual and more about the collective flow.

ABThis reminds me of aerial views of classical dance formations. I know that a few of your works directly reference Balanchine and that you’re formally trained in ballet. Do you think about that language often?

MHMany of my templates are inspired by ballet, especially works by Balanchine. When you’re performing in a piece like that, there are all of these tricks for making sure you’re aligned correctly. Being in the corps de ballet is very much about creating large formations by focusing on smaller visual and architectural cues and spatial relationships. But I also pulled references from Busby Berkeley and things like air shows. The inspirations for PLAY’s sequences draw from many different scales and mediums.

ABAnd how do you create choreographic formulas based on ordinary movement?

MHAs a starting point, I take quotidian gestures and movements and then put them on a loop and set them in formation. For example, I might start with a very specific type of walk or a limp, and then I’ll wonder what it looks like if you have eight people doing that same limp in synchrony from one end of the room to the other in a V shape, like a flock of birds. And then in seeing that, I realize that the limp actually contains all of these nuances, and I begin to sculpt it further from there. So I would say it’s a fusion of pedestrian movements, which I like to call choreographic readymades, and more formal templates that come from cinema, nature, and my ballet background.

you realize which behaviors are unconscious and which are conscious. It brings up the question of who’s being choreographed: are you choreographing your day, or is a machine or workflow choreographing your day?

Madeline Hollander

ABIs narrative something that you welcome or work against?

MhI’m always interested in that point where one can either anthropomorphize or de-anthropomorphize. I look for that flicker moment where you can see expression in a dancer or you can see a very abstract form. And that can depend on where you’re standing or how you’re feeling. When I’m working with humans, I usually try to find ways to de-anthropomorphize first so that people can look at the kinetic forms, and then I bring back the emotion or the message after that. With the chairs, it’s the opposite, because they’re already objects. So first we wondered how we could map on as much personality as possible, and then we started lowering the threshold so that they could enter that same flicker space: Are they having a conversation, or are they just moving in parallel?

ABThe flicker goes between narrative and form?

MHRight, and it can catch someone off guard in both directions. You see a narrative and then it becomes a form, or you see a form and all of a sudden it turns into a drama.

ABIn Gagosian’s booth at this year’s New York Art Book Fair [at MoMA PS1, September 21–23], we’re showing William Forsythe’s Lectures from Improvisation Technologies (2011). The projected videos show him drawing lines in space, creating a lexicon for dancers to improvise from. You were saying in the gallery the other day that the vocabulary that has accumulated around PLAY is a hybrid of many different disciplines—dance, gaming, animation, and programming—so you’re creating an entirely new syncretic language in order to leave it up to chance. Could you speak to that paradox of creating a formula for improvisation?

MHYeah. In order to create a composition, even if that composition is based on chance or improv, there needs to be a horizon line and some type of “gravity.” The lexicon sets up the basic rules so that someone can learn how to behave in the landscape. So much of performance is about anticipation, so if there is no horizon line, it’s hard to pay attention; there is nothing to hold on to. In all of my pieces, we try to develop a movement vocabulary that’s very specific to the site. Then someone can either follow along and uncover the rules, or see it as more of a pinball machine.

ABDo you prefer one result over the other?

MHFor me, it’s more exciting when you can read it as a pinball machine. You start to imagine the virtual nodes throwing the dancers and objects in different directions. My favorite part of pinball is watching someone playing and seeing their body move and react in the same way as the ball.

ABLike when you’re bowling and you sway your body in the direction you want the ball to go.

MHExactly. And that’s such a perfect example of how we automatically anthropomorphize these objects as extensions of our own lives and bodies.

ABThis corporeal relation is a major aspect of sculpture as well. Especially in Urs’s work, which often uses scale and material to challenge the way we interact with things. Where do you think you and Urs overlap?

MHDiagraming is probably the number one way that Urs and I communicate. A diagram is a movement and a drawing at the same time.

ABHas anything surprised you about choreographing the chairs?

MHOne of the things that’s become really clear is that the piece is almost a personality test for viewers. You learn so much about someone when you see them interacting with the chairs for the first time and making decisions about stepping back, stepping forward, being more aggressive, or just wanting to observe. In my work I avoid a certain theatricality. A dancer isn’t going to have a direct dramatic interaction with someone, whereas the chairs get to do that because there’s a higher threshold that they can push without it becoming theatrical. It’s a really nice inverse to the way I usually work.

Urs Fischer: PLAY with choreography by Madeline Hollander, Gagosian West 21st Street, New York, September 6–October 13, 2018