Sarah Sze: Timelapse

Francine Prose ruminates on temporality, fragility, and strength following a visit to Sarah Sze’s exhibition Timelapse at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

March 25, 2020

In this series we invite artists and writers to tell us about works of art, literature, film, or music that have influenced their work or are at the forefront of their minds today. In this first installment Sarah Sze writes about five films that live as richly evocative images in her visual memory.

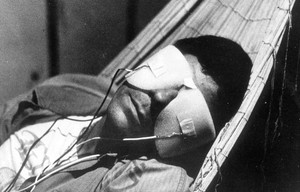

Still from La Jetée (1962), directed by Chris Marker. Photo: Moviestore Collection Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Still from La Jetée (1962), directed by Chris Marker. Photo: Moviestore Collection Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

I usually remember an entire film through a single moment—one still image. So I’m attracted to those that somehow reveal film as just a composition of still images—a string of single frames with infinitesimal shifts between them to make the picture appear to move and get the cinematic flow of time going. Strangely, I often forget the entire narrative of a film for that one image. Although looking back over the films I’ve listed here, I recognize a kind of narrative trend—of sagas that reach to the ends of the earth and play with the art of brinkmanship in life and death.

I first saw Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) during my first month in college in 1987. It starts with the line “This is the story of a man marked by an image of his childhood.” The main character is sightless—his eyes covered by a makeshift eye mask (of cotton balls and tape)—and the screen itself becomes a conduit for the images in his mind, images of the past that have burned into memory. He’s the post-apocalyptic subject of an experiment in time-travel, and the viewer is witness to the transmission of images from his pre-apocalyptic mind. Marker reveals the medium of film itself as a timekeeper and an experiment in memory, thrusting us forward into the future—the film is set after a third world war—and backward into the past—he restores filmmaking to its roots: a string of black-and-white photos, employing the simplest of special effects. La Jetée does not define itself as a film at all but rather as a photo-roman (photo-novel). Stripped bare in 28 minutes of black-and-white stills, it’s a montage that replicates the gaps in our recollections, and it has the rhythm of memories: le passage de l’image, like a Nan Goldin slideshow. The voice of the straightforward, Kafka-like narrator in the film states: “Nothing tells memories from ordinary moments. Only afterwards do they claim remembrance.”

Still from In the Mood for Love (2000), directed by Wong Kar-wai. Photo: RGR Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

Among the many films influenced by La Jetée (Mad Max, The Terminator, 12 Monkeys, to name a few) is Wong Kar-wai’s multi-period narrative 2046 (2004), but I’ll go for his game-changer In the Mood for Love (2000) instead. We are thrust in this film into an exiled Shanghainese community in Hong Kong where most of the characters speak in Shanghai dialect, which my grandmother spoke to me, desperate for her grandchildren to speak Chinese. The film is deeply stylish and stylized, but it’s not only about style. The camera tracks the days by the woman’s change of classic qipao, closing in on the dresses like abstract paintings. The characters are filmed as much from the back as from the front. The faintest sensation of touch—accidental, slight, in passing, and unreciprocated—is captured throughout. Much more than plot or narrative, it’s about an atmosphere of sexual tension and loss, the innuendo of love affairs that you feel but never see. The images of beauty and its underbelly are haunted by Shigeru Umebayashi’s incredible music, “Yumeji’s Theme.”

A line from La Jetée—“If they could conceive of or dream of another time, perhaps they would be able to enter into it”—reminds me of Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev (1966), where life is painted as an everlasting poem with the tempo of the placid or the pensive. Both directors have an almost photographic sensibility, holding the image in a protracted gaze. From each, one moment is burned in my memory. In Pather Panchali, which takes place in the early part of the twentieth century, there’s the unforgettable image of the child Apu in his dhoti, running across a field, dwarfed by the long white grasses, looking for his sister. In Andrei Rublev, set in the abject tail-end of the Middle Ages, it’s the slow-motion image of a horse turning over on its back and rolling slowly from one side to the other, trying to get up onto its hooves. That’s my all-time favorite image in any film. Both directors draw heavily from Sergei Eisenstein’s methods of montage to drive the collage of unrelated images into collision to create metaphor.

Still from Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), directed by Peter Weir © McElroy & McElroy. Photo:

TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy Stock Photo

For me, Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) is all but reduced to the charged image of schoolgirls in white dresses climbing the huge rock in a heat wave, with the buzzing of insects and the recurrent, ominous pan-flute score by Gheorghe Zamfir. But in narrative terms, it presages so many later films about femininity and the psychic power of women, like The Virgin Suicides, The Blair Witch Project, or Raise the Red Lantern. It’s also a horror movie in many ways, with its brooding implication of evil that goes unspoken, an insidiousness that asserts itself over the viewer.

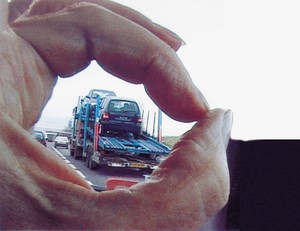

Still from The Gleaners and I (2000), directed by Agnès Varda © ciné-tamaris

Agnès Varda, a close friend of Marker’s, began with groundbreaking films like Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), where she worked in real time—it’s a fiction but depicts events as they occur over a two-hour timespan, as the title suggests. Varda was a creative force of nature, always playfully skirting this line between fiction and documentary in her use of time. I got to know her when she filmed my art for The Gleaners and I (2000), at a stage in her oeuvre where she exploded the meaning of what a documentary could be. I love the scene in The Gleaners and I when she is filming the ground and she lets us see the lens cap swinging on a string in front of the camera, intruding on the frame of the shot. As a narrator, she talks about how funny she finds it, showing her hand, and what a film is and does, asking the perennial question, Who is looking at whom?

Still from Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), directed by Benh Zeitlin. Photo:

Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo

Fiction that toys with documentary direction seemed to be pushed to its limits in the incredible acting of Quvenzhané Wallis as Hushpuppy and Dwight Henry as her father, Wink, in Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012). How the dialogue was directed so naturally is a total mystery to me. I can never forget the image of Wink running down a path in a hospital gown—the shame and anonymity of that gown, his back exposed, not being able to admit to his daughter that he has terminal cancer. That scene was such an extraordinary subversion of masculinity and of a father’s desire to protect and provide.

This prophetic image from a vivid saga of retro-futurism is the last one I will leave you with. The past imagines the future, which is very present. From the script of La Jetée: this is a time for “calling past and future to the rescue of the present.”

Sarah Sze’s art utilizes genres as generative frameworks, uniting intricate networks of objects and images across multiple dimensions in sculpture, painting, drawing, printmaking, and video installation. Her works prompt microscopic observation while evoking a macroscopic perspective on the infinite.

Francine Prose ruminates on temporality, fragility, and strength following a visit to Sarah Sze’s exhibition Timelapse at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

In this video, Sarah Sze elaborates on the creation of her solo exhibition Timelapse, on view through September 10, 2023. The show features a series of site-specific installations throughout the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, that explore her ongoing reflection on how our experience of time and place is continuously reshaped in relationship to the constant stream of objects, images, and information in today’s digitally and materially saturated world. In Sze’s reimagination of the Guggenheim’s iconic architecture, designed in the 1940s by Frank Lloyd Wright, the building becomes a public timekeeper reminding us that timelines are built through shared experience and memory.

On the occasion of her exhibition of recent paintings, presented at Gagosian in Rome, Pat Steir met with fellow artist Sarah Sze for a wide-ranging discussion—from shared inspirations and influences to the role of chance, contingency, place, and time in painting.

Sarah Sze writes on a recent collage.

The Summer 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Joan Jonas’s Mirror Piece 1 (1969) on its cover.

Hear Sarah Sze speak about her most recent work, including the panel painting Picture Perfect (Times Zero) and the multimedia installation Plein Air (Times Zero) (both 2020). Discussing the relationship between painting and sculpture in her practice, she explains how she creates structure and its inverse, instability, in her layering of images, putting the viewer in the position of active discovery.

Louise Neri talks with Sarah Sze about the new primacy of the image in her explorations between and across mediums. They spoke on the occasion of an exhibition of Sze’s work at Gagosian, Rome, comprising collaged panel paintings, a large-scale video installation, and an outdoor sculpture fashioned from a natural boulder.

Join Sarah Sze as she talks about the questions that drive her work. She describes creating immersive experiences that blur the lines between time, memory, and space—and between art and life.

The inaugural presentation of Frieze Sculpture New York at Rockefeller Center opened on April 25, 2019. Before the opening, Brett Littman, the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum and the curator of this exhibition, told Wyatt Allgeier about his vision for the project and detailed the artworks included.

Join Sarah Sze in her studio as she prepares for an exhibition of new work in Rome.

In this Shortlist series we invite artists and writers to tell us about works of art, literature, film, or music that have influenced their work or are at the forefront of their minds today. Here Jim Shaw shares a selection of songs he listens to while working, from new discoveries to childhood staples. Shaw writes of the balance between delight and regret, hope and gloom in his playlist.

Spencer Sweeney shares a selection of songs that have punctuated his journey through the pandemic and ponders the expressive powers of a playlist.